When the novel coronavirus appeared in the United States in early 2020, experts — both medical and political — had little information about how best to handle it. It seemed, based on preliminary and ultimately inaccurate information, to spread through contact, meaning that the focus became hand-washing and Clorox wipes instead of covering one’s mouth. There was, however, full understanding of that lack of certainty, meaning that authorities tended to err on the side of caution to keep the virus as contained as possible and limit its damage.

Politics

The sliding definition of ‘lockdown’ in U.S. politics

|

|

What followed the virus’s arrival, then, was an ad hoc effort to restrict person-to-person interactions as much as possible. Bans on large gatherings were implemented and recommendations were made to remain at home as much as possible, with compliance voluntary. The hard-and-fast prohibitions centered on places where people might tend to congregate, such as bars and schools. It was a restriction of options more than a restriction of activity.

This was appreciably different from what had already been underway in China. There, movement was at times restricted entirely as the autocratic government sought to stamp out transmission of the virus in one fell swoop. First the city of Wuhan, where the virus was first detected, then other cities as cases emerged. These were “lockdowns” in an often literal sense: people forced to stay in place in an effort to halt the virus. When looser rules arrived in the United States months later, the same term was often applied by Americans to a very different process.

The effects of that have lingered. Over the past three years, the idea that the United States had a system of “lockdowns” has persisted, and an array of responses to the virus has been loosely grouped under that umbrella: remote schooling, restaurant closings, restrictions on entering facilities. Some of the closures and limits arguably or demonstrably incurred more cost than the value they offered, but none were “lockdowns” in the Wuhan sense.

Democratic leaders and locations moved first to impose restrictions — in part because the virus first spread widely in Democratic places. But soon, President Donald Trump and Republican leaders joined the push to impose limits on person-to-person contact. The White House announced a national emergency on March 13, 2020, and, a few days later, guidelines aimed at limiting in-person interactions. Other officials took the same steps: On March 17, for example, Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) announced the closure of bars and restaurants for 30 days.

The era of collective, bipartisan interest in stopping the spread (as the vernacular had it) was short-lived. The economy was understandably hammered by closures of businesses and schools. Trump, with an eye on his upcoming reelection campaign, turned against widespread shutdowns fairly quickly, suggesting that maybe by Easter — April 12, 2020 — things could be close enough to normal that churches could be filled once again. He and his advisers revised downward their recommendations for states to reopen (another bit of vernacular conflating the specific closures with a state’s status), and then Trump quickly demanded that states get back to normal regardless.

People in a number of states began protesting pandemic rules. Trump, eager to see the economy rebound completely, offered his approval. At first, most Americans disagreed with Trump’s encouragement of the protests, but a line had been crossed. Particularly as the year wound on and the pandemic continued to depress Trump’s poll numbers, the political right cast overbearing government officials as a threat to individual liberty and characterized the “lockdowns” — by now seemingly meaning nearly any covid-19 response unpopular on the right — as the embodiment of the threat.

It’s certainly true that Republican officials (and Republicans) have consistently been less fervent about coronavirus responses than Democratic officials (and Democrats). The partisanship of the pandemic is broad and well-documented. But the idea that Democrats enacted “lockdowns” or seek new “lockdowns” persists not because there have been calls even to introduce new limits on in-person interaction. Rather, it endures because it is politically useful to suggest that Democrats want to do so — since using “lockdown” as a synonym for “government forcing you to do something” plays into long-standing Republican rhetoric.

As the 2020 election approached, Trump’s White House was touting his successes, including that he had managed to save lives during the pandemic “while ending harmful lockdowns.” DeSantis began promoting “Don’t Fauci my Florida” gear on his campaign website, picking up on Trump’s scapegoating of the country’s top infectious-disease doctor, Anthony S. Fauci, as a way of demonstrating opposition to efforts to contain the virus. These were pivots away from their embrace of early measures to slow the virus’s spread, measures that had both become unpopular with Republican voters — thanks largely to Trump’s election-trail rhetoric — and that had often been exaggerated for effect.

The Biden White House has been asked repeatedly whether President Biden supports “lockdowns.” In February, for example, a reporter asked press secretary Jen Psaki about the idea.

“The president has been clear we’re not pushing lockdowns; we’ve not been pro-lockdown,” she replied. “That has not been his agenda. Most of the lockdowns actually happened under the previous president.”

It’s probably not helpful for the administration to conflate what happened in 2020 with “lockdowns,” given that, more recently, the current press secretary was asked for a White House response to protests against China’s very different lockdowns. But it also probably doesn’t matter. That Biden has pushed Americans — with decreasing force as time goes on — to take steps to combat the virus means that he, not Trump, is seen by much of the country as the lockdown president and his party as the lockdown party.

More because that perception is useful to Biden’s opponents than because it’s accurate. Because, in short, it fits into the long-standing frame of Democrats as the party of big government intrusion and Republicans as the party of do-what-you-want.

And that’s also why it’s likely to stick.

Politics

GOP strategist reacts to Trump’s ‘unconventional’ request – CNN

GOP strategist reacts to Trump’s ‘unconventional’ request

Donald Trump’s campaign is asking Republican candidates and committees using the former president’s name and likeness to fundraise to give at least 5% of what they raise to the campaign, according to a letter obtained by CNN. CNN’s Steve Contorno and Republican strategist Rina Shah weigh in.

Politics

Anger toward federal government at 6-year high: Nanos survey – CTV News

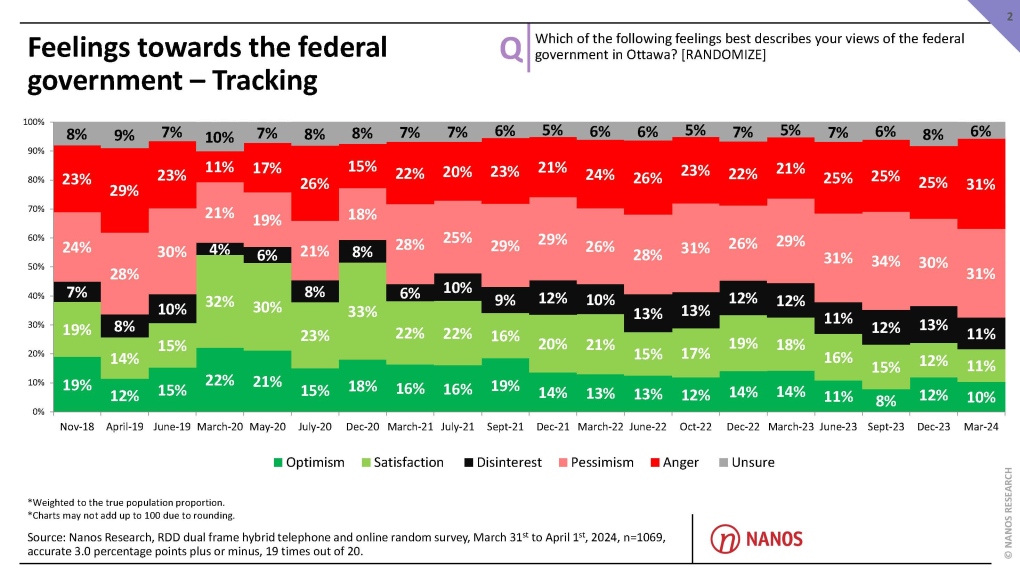

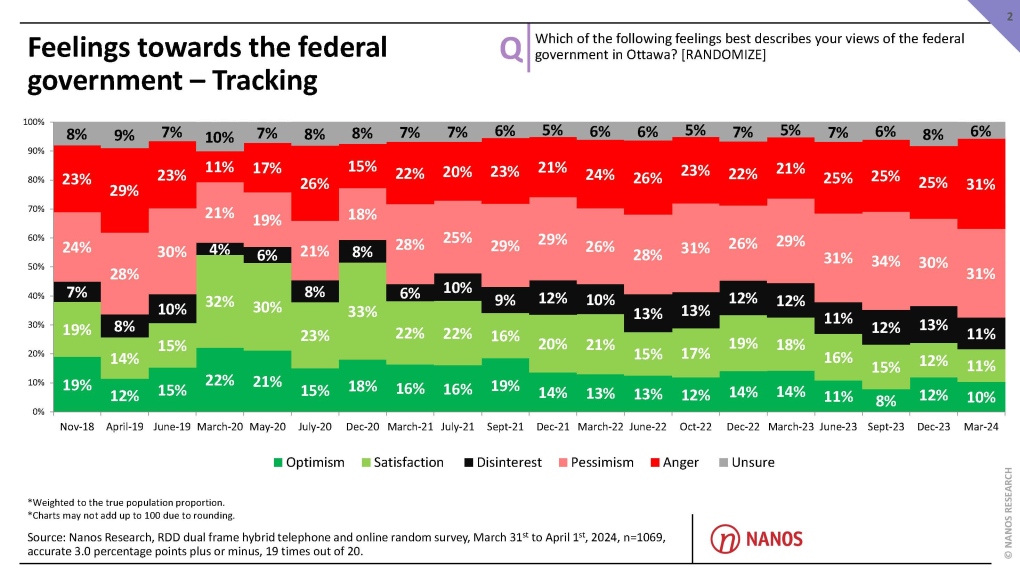

Most Canadians in March reported feeling angry or pessimistic towards the federal government than at any point in the last six years, according to a survey by Nanos Research.

Nanos has been measuring Canadians’ feelings of optimism, satisfaction, disinterest, anger, pessimism and uncertainty toward the federal government since November 2018.

The latest survey found that optimism had crept up slightly to 10 per cent since hitting an all-time low of eight per cent in September 2023.

However, 62 per cent of Canadians said they feel either pessimistic or angry, with respondents equally split between the two sentiments.

(Nanos Research)

“What we’ve seen is the anger quotient has hit a new record,” Nik Nanos, CTV’s official pollster and Nanos Research founder, said in an interview with CTV News’ Trend Line on Wednesday.

Only 11 per cent of Canadians felt satisfied, while another 11 per cent said they were disinterested.

Past survey results show anger toward the federal government has increased or held steady across the country since March 2023, while satisfaction has gradually declined.

Will the budget move the needle?

Since the survey was conducted before the federal government released its 2024 budget, there’s a chance the anger and pessimism of March could subside a little by the time Nanos takes the public’s temperature again. They could also stick.

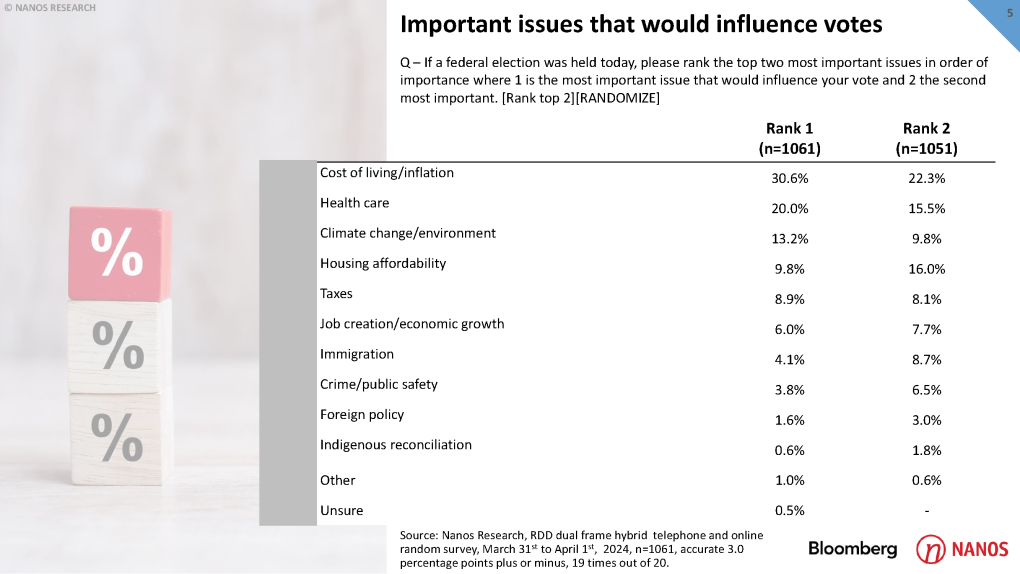

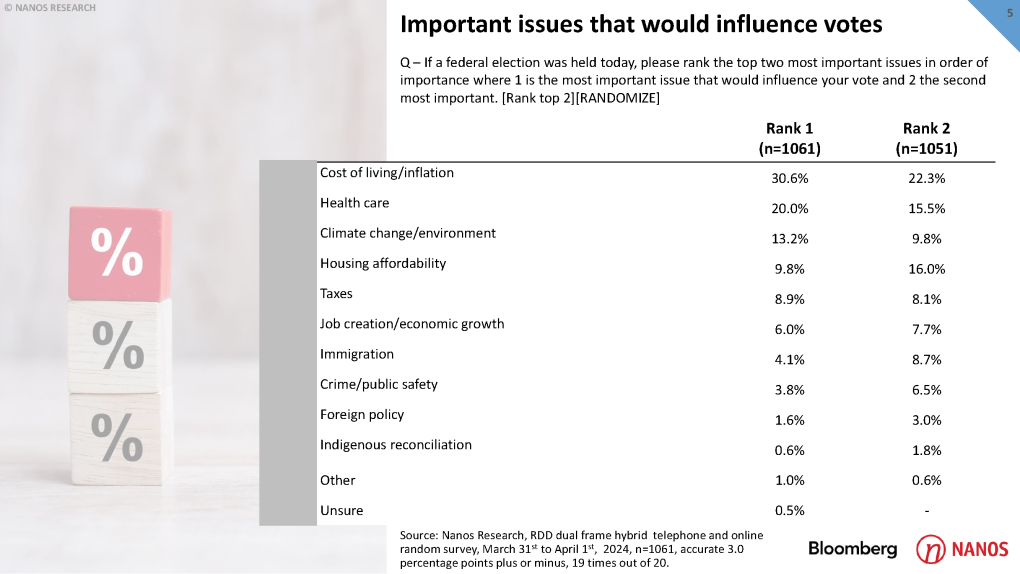

The five most important issues to Canadians right now that would influence votes, according to another recent Nanos survey conducted for Bloomberg, include inflation and the cost of living, health care, climate change and the environment, housing affordability and taxes.

With this year’s budget, the federal government pledged $52.9 billion in new spending while promising to maintain the 2023-24 federal deficit at $40.1 billion. The federal deficit is projected to be $39.8 billion in 2024-25.

The budget includes plans to boost new housing stock, roll out a national disability benefit, introduce carbon rebates for small businesses and increase taxes on Canada’s top-earners.

However, advocacy groups have complained it doesn’t do enough to address climate change, or support First Nations communities and Canadians with disabilities.

“Canada is poised for another disastrous wildfire season, but this budget fails to give the climate crisis the attention it urgently deserves,” Keith Brooks, program director for Environmental Defence, wrote in a statement on the organization’s website.

Meanwhile, when it comes to a promise to close what the Assembly of First Nations says is a sprawling Indigenous infrastructure gap, the budget falls short by more than $420 billion. And while advocacy groups have praised the impending roll-out of the Canada Disability Benefit, organizations like March of Dimes Canada and Daily Bread Food Bank say the estimated maximum benefit of $200 per month per recipient won’t be enough to lift Canadians with disabilities out of poverty.

According to Nanos, if Wednesday’s budget announcement isn’t enough to restore the federal government’s favour, no amount of spending will do the trick.

“If the Liberal numbers don’t move up after this, perhaps the listening lesson for the Liberals will be (that) spending is not the political solution for them to break this trend line,” Nanos said. “It’ll have to be something else.”

Conservatives in ‘majority territory’

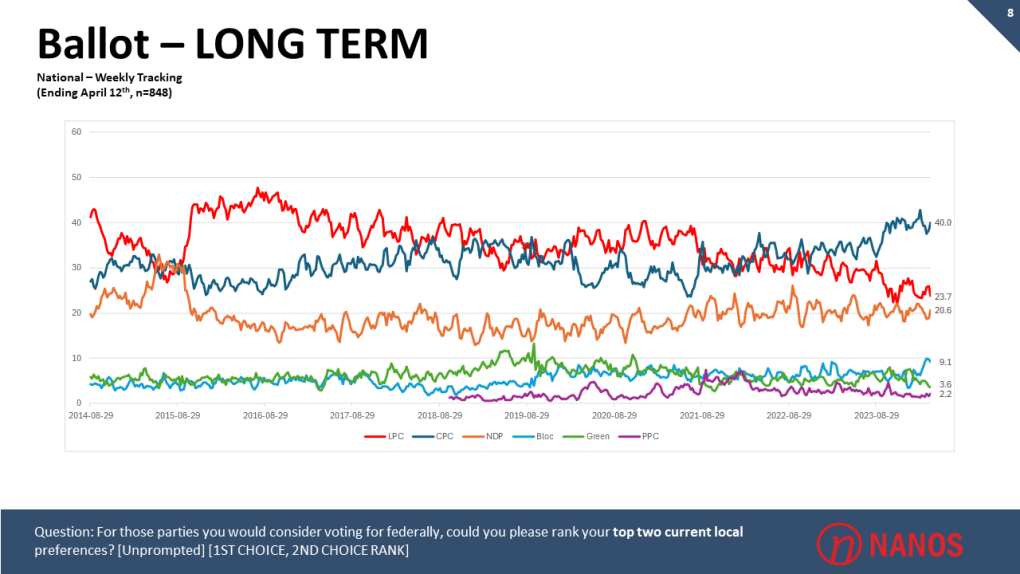

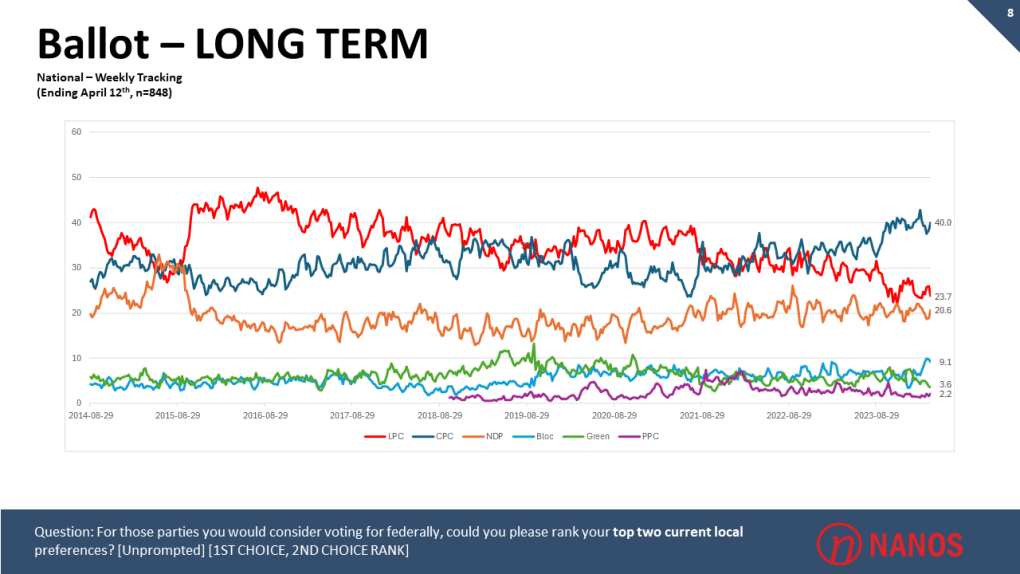

While the Liberal party waits to see what kind of effect its budget will have on voters, the Conservatives are enjoying a clear lead when it comes to ballot tracking.

“Any way you cut it right now, the Conservatives are in the driver’s seat,” Nanos said. “They’re in majority territory.”

According to Nanos Research ballot tracking from the week ending April 12, the Conservatives are the top choice for 40 per cent of respondents, the Liberals for 23.7 per cent and the NDP for 20.6 per cent.

Whether the Liberals or the Conservatives form the next government will come down, partly, to whether voters believe more government spending is, or isn’t, the key to helping working Canadians, Nanos said.

“Both of the parties are fighting for working Canadians … and we have two competing visions for that. For the Liberals, it’s about putting government support into their hands and creating social programs to support Canadians,” he said.

“For the Conservatives, it’s very different. It’s about reducing the size of government (and) reducing taxes.”

Watch the full episode of Trend Line in our video player at the top of this article. You can also listen in our audio player below, or wherever you get your podcasts. The next episode comes out Wednesday, May 1.

Methodology

Nanos conducted an RDD dual frame (land- and cell-lines) hybrid telephone and online random survey of 1,069 Canadians, 18 years of age or older, between March 31 and April 1, 2024, as part of an omnibus survey. Participants were randomly recruited by telephone using live agents and administered a survey online. The sample included both land- and cell-lines across Canada. The results were statistically checked and weighted by age and gender using the latest census information and the sample is geographically stratified to be representative of Canada. The margin of error for this survey is ±3.0 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

With files from The Canadian Press, CTV News Senior Digital Parliamentary Reporter Rachel Aiello and CTV News Parliamentary Bureau Writer, Producer Spencer Van Dyke

Politics

The MAGA Right is Flirting With Political Violence – Vanity Fair

The MAGA right exists in a perpetual state of overheated grievance. But as the November election nears, the temperature seems to be rising, getting dangerously high.

This week, following Gaza war protests that disrupted travel in major American cities Monday, Senator Tom Cotton explicitly called on Americans to “take matters into [their] own hands” to get demonstrators out of the way. Asked to clarify those comments Tuesday, Cotton stood by them, telling reporters he would “do it myself” if he were blocked in traffic by demonstrators: “It calls for getting out of your car and forcibly removing” protestors,” he said.

X content

This content can also be viewed on the site it originates from.

The right-wing senator’s comments came on the heels of Kari Lake, the GOP candidate for Senate in Arizona, suggesting supporters should arm themselves for the 2024 election season. “The next six months is going to be intense,” she said at a rally Sunday. “And we need to strap on our—let’s see, what do we want to strap on? We’re going to strap on our seat belt. We’re going to put on our helmet or your Kari Lake ballcap. We are going to put on the armor of God. And maybe strap on a Glock on the side of us, just in case.”

And those comments came a couple weeks after Donald Trump, who regularly invokes apocalyptic and violent rhetoric, shared an image on social media depicting President Joe Biden—his political rival—hog-tied in the back of a pick-up truck. “This image from Donald Trump is the type of crap you post when you’re calling for a bloodbath or when you tell the Proud Boys to ‘stand back and stand by,’” a Biden spokesperson told ABC News last month, referring to the former president’s dog-whistle to extremist groups during a 2020 debate and to cryptic remarks he’s made from rally stages this spring suggesting Biden’s reelection would mean a “bloodbath”—for the auto industry and for the border. This kind of thing is nothing new—not for Trump, not for his allies, and not in American history, which is what makes these flirtations with political violence all the more dangerous.

We’ve seen where this kind of reckless rhetoric can lead. Throughout Trump’s first campaign for president, it led to eruptions of violence at his rallies, which he openly encouraged: “Knock the crap out of ‘em, would you?” he told supporters of hecklers. It also inflamed tensions throughout his presidency, which culminated with his instigating a violent insurrection at the United States Capitol. According to a PBS Newshour/NPR/Marist poll this month, 20 percent of Americans believe violence may be necessary to get the country on track. A disturbing new study out of University of California-Davis found openness to political violence was even higher among gun owners, particularly those who own assault weapons, recently purchased their firearms, or carry them in public. And an October survey by the Public Religion Research Institute and the Brookings Institution suggested that support for political violence, while still limited, appears to be increasing, with nearly a quarter of respondents overall—and a third of Republicans—agreeing with the statement: “Patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.”

“It looks like the temperature has gone up across the board, but especially among Republicans,” Robert P. Jones, president and founder of PRRI, told Axios of the survey last fall. That’s no accident. It’s the kind of political climate you get when a sitting senator promotes vigilantism, a Senate candidate calls on supporters to take up arms, and a major party embraces or enables a demagogue. “Political violence,” as Biden campaign communications director Michael Tyler put it a couple weeks ago, “has been and continues to be central to Donald Trump’s brand of politics.”

More Great Stories From Vanity Fair

-

Investment24 hours ago

Saudi Arabia Highlights Investment Initiatives in Tourism at International Hospitality Investment Forum

-

Tech17 hours ago

Tech17 hours agoCytiva Showcases Single-Use Mixing System at INTERPHEX 2024 – BioPharm International

-

Politics24 hours ago

Politics24 hours agoThe Earthquake Shaking BC Politics

-

Science23 hours ago

Science23 hours agoNasa confirms metal chunk that crashed into Florida home was space junk

-

Investment23 hours ago

Investment23 hours agoBill Morneau slams Freeland’s budget as a threat to investment, economic growth

-

News19 hours ago

Tim Hortons says 'technical errors' falsely told people they won $55K boat in Roll Up To Win promo – CBC.ca

-

Politics22 hours ago

Politics22 hours agoFlorida's Bob Graham dead at 87: A leader who looked beyond politics, served ordinary folks – Toronto Star

-

Health13 hours ago

Health13 hours agoSupervised consumption sites urgently needed, says study – Sudbury.com