Art

Art during the time of coronavirus – Maclean's

This is the first of a series of essays from Canadian authors on the coronavirus and how it affects our everyday lives.

Heather O’Neill is an award winning writer based in Montreal. Her novels include Lullabies for Little Criminals and The Lonely Hearts Hotel.

Pandemics are notorious for upending all of society. Artists are notorious for creating their art under the most perilous and inopportune circumstances. They create in poverty, under repressive regimes, in prison, in the margins, after long late night shifts at a diner. When news of the pandemic began to take hold on the popular psyche and began changing our daily lives, I thought it might feel pointless to write anything given the gravity of the situation. But I am still writing every day, even more devotedly than before. Throughout history, art has continued to be created and consumed during times of plagues and global health crises. So art will be created now. Which begs the questions: What sort of art has been created during pandemics? And what purpose does art serve during them?

In Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, a group of women and three handsome men they chance upon, flee Florence in order to escape the Plague of 1348. They hole themselves up in a palace and each take turns telling a story at night. Boccaccio was the first to use a framing device, which is a narrative technique whereby a story is surrounded by a secondary story. The tales recited in the evening were witty, provocative, and seriously filthy.

They were not tales of the plague but of humanity in all its distracting joys. They used storytelling as a way to stay alive. It is similar to today. My daughter works at a bookstore and the day before it closed because of the pandemic, people rushed in to buy stacks of books. They wanted tales of loveliness, horror and courage. After its doors were shuttered, people began to purchase books online. My daughter leaves the stacks of books on a table in the vestibule and people enter the quarantined site all day to retrieve these necessary items.

Since self-isolation began, people all over the world have taken to putting up live streams on Instagram to communicate stories. They recite poems, cook vegetables, play music and entertain in any way they can. Because the need to hear stories is as strong as it is to tell them.

Each day of storytelling in The Decameron ends with a song performed by one of the characters. New secular musical forms emerged from the 14th century plague. Poet Guillaume de Machaut of France began setting his poems to music. And by 1365, the ballade had become one of the most popular secular forms.

During the plague, there were processions of wanderers loudly singing songs. Litanies—a chant that involves a supplication recited by the clergy, followed by a response from the congregation—became very popular. There was a call and response from the roving devotional procession to those in the street and the audiences at home. They created a sense of community in the social rupture caused by a pandemic.

Interestingly enough, back then in Milan, where risk of the contagion was high inside churches, the pious joined together in sacred songs from their open windows and doors. This exact phenomenon happened in Italy recently when quarantined citizens took to their balconies to play instruments and sing together. They played everything from accordions, tubas, violins, flutes, guitars and lots and lots of tambourines. And they are filled with infectious communal spirit while doing so.

Then there are those artists who have used the isolation of the plague to their advantage to delve into their own works. Shakespeare was notable in this respect.

When Shakespeare was a baby, a plague was ravaging the city, having already killed both his older siblings. It is speculated that Shakespeare’s exposure to the plague as an infant caused him to develop immunity. Who can say if this is true, but he survived four major plagues outbreaks that were severe enough to close theatres—1582, 1592, 1603 and 1607—during his lifetime.

Whenever there were plagues during the Renaissance, the theatres were shuttered en masse.

Shakespeare wrote in fits. He would not produce a play for several years and then go through a creative streak. In 1606, when he was 42 years old, he was in a fallow period, and it might have seemed to him that his best works were perhaps now behind him. But then when the plague closed down theatres, forcing him away from the wonderful mayhem of production, Shakespeare wrote King Lear, Antony and Cleopatra, and Macbeth.

These are masterworks of tragedy and introspection, which delve into the deepest realms of paranoid human solitude.

And what is the point of creating such twisted tales during dark times? Aristotle’s Poetics claims that by witnessing grieving, fear and pity in tragedy, we fear and grieve less when they happen in real life. Which explains why everyone is streaming Steven Soderbergh’s 2011 movie Contagion. I rewatched it last night and I have to say, I found it comforting.

The tragic figure of St. Sebastien, who was tied to a tree and pierced with arrows by the Romans, is considered to be the patron saint of plagues. During the plague years, paintings and altars of him were created all over Europe.

There are two states in which St. Sebastien is generally depicted: in one, he is in a state of degraded agony, pierced and mutilated by innumerable arrows; in others, he is portrayed in his stunning beauty, arrows sticking out of him like peacock feathers. Sebastien was an adonis. There was a painting of him in his super–babe state that had to be taken down when a woman was caught masturbating to it.

St. Sebastien, in addition to being the patron saint of the plague, is also the saint of homoerotic desire. There is a famous photograph by artist David Wojnarowicz, who was diagnosed HIV positive in 1987, where his mouth is sewn together with thick thread, attesting to the silencing he was facing, that puts me in mind of St. Sebastien.

Because the AIDS epidemic struck groups that were already marginalized, such as gay men and intravenous drug users, they faced—in addition to illness—the horror of blame, hatred and social isolation. Victims were further victimized by a society that refused to immediately disseminate information, medical funding into research and care for patients. As Wojnarowicz wrote in his memoir, “My rage is really about the fact that when I was told that I’d contracted this virus, it didn’t take me long to realize that I’d contracted a diseased society as well.”

Whereas the world wanted AIDS patients to disappear and be non-persons, artists like Wojnarowicz created portraits that made their tragedy magnificent. It rendered them visible. And thus art during this plague was a form of activism.

Wojnarowicz’s art has been repeatedly censored, as has Boccaccio’s Decameron. Art has always been a method of giving voice to the alienated and voiceless. Because they are articulating the experiences of the oppressed and disenfranchised, they do not articulate themselves in mainstream art forms. Thus the newness of their work causes it to be interpreted as shocking, discordant, lewd. Like Mary Shelley, the English novelist who wrote Frankenstein, artists stitch together body parts from the graves of the murdered and neglected, and reanimate them. They exist in the world, demand their space and to be called beautiful. David Wojnarowicz’s funeral was the first memorial during the AIDS epidemic that was a protest march.

In whatever form it takes, art will be created during plagues. There will be more of a demand for it from people, from those who want to be amused, those who want to be consoled, those who are looking for a community, and those who want to be able to be heard. These periods of hardship indelibly mark art. It changes its subject matter, but more importantly, it changes the very structure and possibilities of art. And all art that follows contains the echoes and scars of all we have been through.

MORE ABOUT CORONAVIRUS:

Art

Art and Ephemera Once Owned by Pioneering Artist Mary Beth Edelson Discarded on the Street in SoHo – artnet News

This afternoon in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, people walking along Mercer Street were surprised to find a trove of materials that once belonged to the late feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson, all free for the taking.

Outside of Edelson’s old studio at 110 Mercer Street, drawings, prints, and cut-out figures were sitting in cardboard boxes alongside posters from her exhibitions, monographs, and other ephemera. One box included cards that the artist’s children had given her for birthdays and mother’s days. Passersby competed with trash collectors who were loading the items into bags and throwing them into a U-Haul.

“It’s her last show,” joked her son, Nick Edelson, who had arranged for the junk guys to come and pick up what was on the street. He has been living in her former studio since the artist died in 2021 at the age of 88.

Naturally, neighbors speculated that he was clearing out his mother’s belongings in order to sell her old loft. “As you can see, we’re just clearing the basement” is all he would say.

Photo by Annie Armstrong.

Some in the crowd criticized the disposal of the material. Alessandra Pohlmann, an artist who works next door at the Judd Foundation, pulled out a drawing from the scraps that she plans to frame. “It’s deeply disrespectful,” she said. “This should not be happening.” A colleague from the foundation who was rifling through a nearby pile said, “We have to save them. If I had more space, I’d take more.”

Edelson’s estate, which is controlled by her son and represented by New York’s David Lewis Gallery, holds a significant portion of her artwork. “I’m shocked and surprised by the sudden discovery,” Lewis said over the phone. “The gallery has, of course, taken great care to preserve and champion Mary Beth’s legacy for nearly a decade now. We immediately sent a team up there to try to locate the work, but it was gone.”

Sources close to the family said that other artwork remains in storage. Museums such as the Guggenheim, Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney currently hold her work in their private collections. New York University’s Fales Library has her papers.

Edelson rose to prominence in the 1970s as one of the early voices in the feminist art movement. She is most known for her collaged works, which reimagine famed tableaux to narrate women’s history. For instance, her piece Some Living American Women Artists (1972) appropriates Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1494–98) to include the faces of Faith Ringgold, Agnes Martin, Yoko Ono, and Alice Neel, and others as the apostles; Georgia O’Keeffe’s face covers that of Jesus.

A lucky passerby collecting a couple of figurative cut-outs by Mary Beth Edelson. Photo by Annie Armstrong.

In all, it took about 45 minutes for the pioneering artist’s material to be removed by the trash collectors and those lucky enough to hear about what was happening.

Dealer Jordan Barse, who runs Theta Gallery, biked by and took a poster from Edelson’s 1977 show at A.I.R. gallery, “Memorials to the 9,000,000 Women Burned as Witches in the Christian Era.” Artist Keely Angel picked up handwritten notes, and said, “They smell like mouse poop. I’m glad someone got these before they did,” gesturing to the men pushing papers into trash bags.

A neighbor told one person who picked up some cut-out pieces, “Those could be worth a fortune. Don’t put it on eBay! Look into her work, and you’ll be into it.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Art

Biggest Indigenous art collection – CTV News Barrie

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Biggest Indigenous art collection CTV News Barrie

Source link

Art

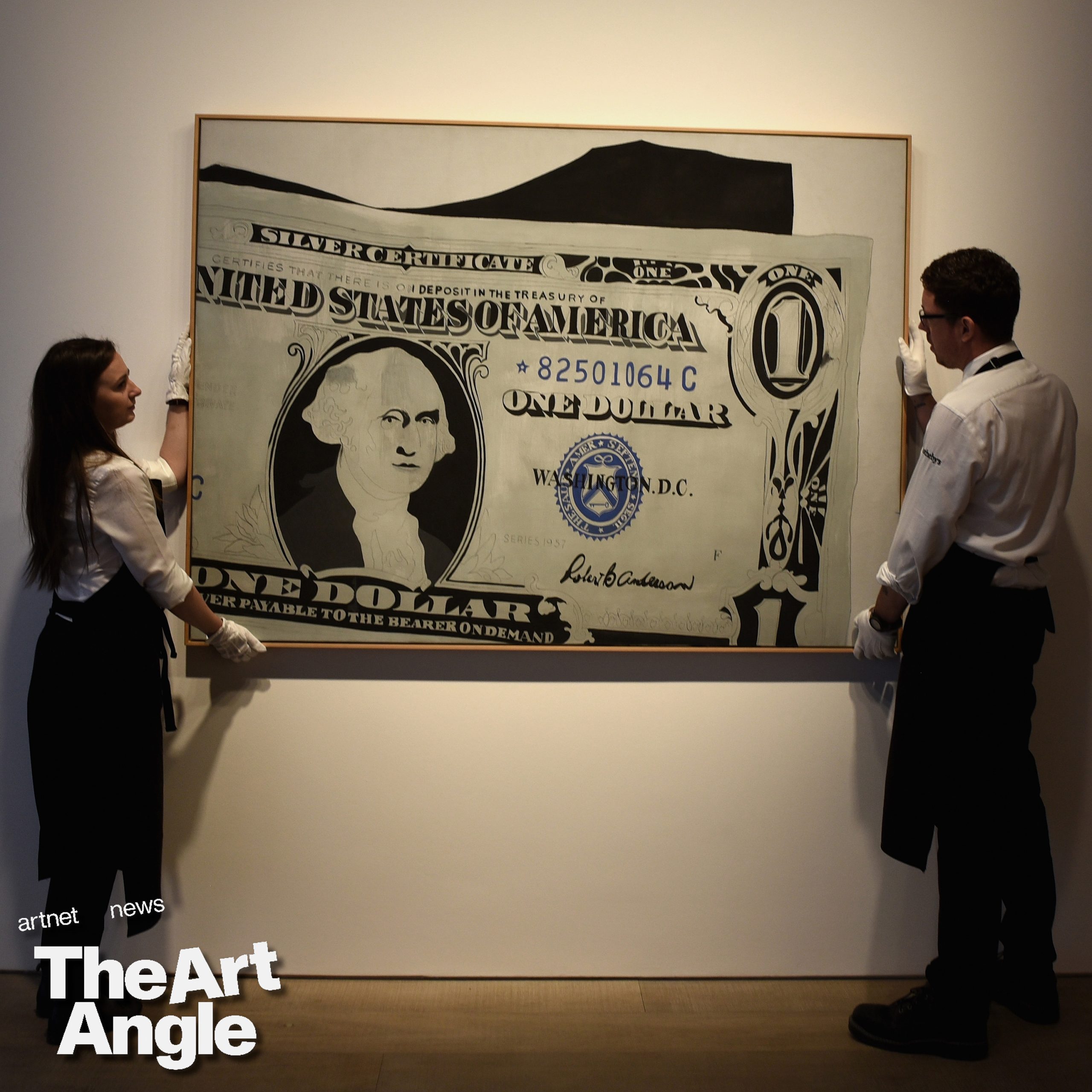

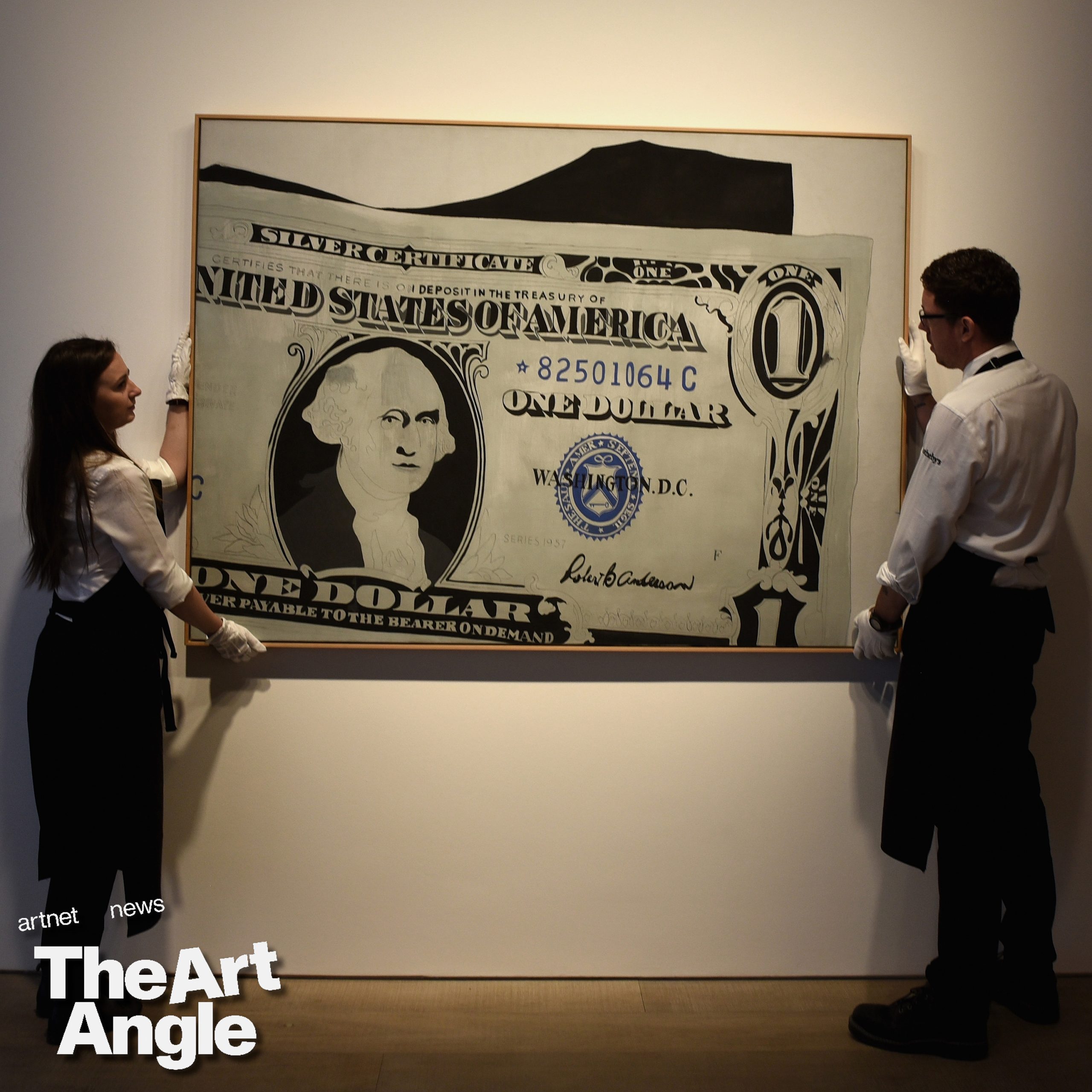

Why Are Art Resale Prices Plummeting? – artnet News

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

-

Media9 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Media11 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Investment10 hours ago

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

-

Media23 hours ago

DJT Stock Jumps. The Truth Social Owner Is Showing Stockholders How to Block Short Sellers. – Barron's

-

Health23 hours ago

Health23 hours agoType 2 diabetes is not one-size-fits-all: Subtypes affect complications and treatment options – The Conversation

-

Business23 hours ago

Tofino, Pemberton among communities opting in to B.C.'s new short-term rental restrictions – Vancouver Sun

-

Business22 hours ago

A sunken boat dream has left a bad taste in this Tim Hortons customer's mouth – CBC.ca

-

News21 hours ago

Best in Canada: Jets Beat Canucks to Finish Season as Top Canadian Club – The Hockey News