Art

Barbara Rose, Critic and Historian of Modern Art, Dies at 84 – The New York Times

She wrote a celebrated college textbook, but, extending her reach beyond academia, she preferred exploring the unfolding art of the present.

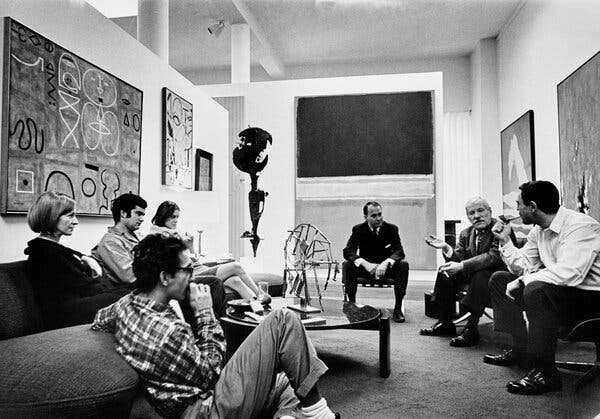

Barbara Rose, the influential art historian and critic who began her career as a champion of Minimalism and wrote about culture with an authority informed by her close friendships with two generations of artists in New York and abroad, died on Friday in Concord, N.H. She was 84.

Her death, in a hospice, was confirmed by her husband, Richard Du Boff, who said that she had had breast cancer for a decade.

Ms. Rose is probably best known as the author of the textbook “American Art Since 1900,” which became a campus perennial in the 1970s. But, extending her reach beyond academia, she preferred exploring the unfolding art of the present.

She was an art critic for Vogue and New York magazines and produced eight documentary films. A devotee of the ritual known as studio visits, she was always traipsing to artists’ lofts to look at their latest paintings and probe for helpful information.

“The reason I interviewed artists is because I really wanted to know the answer to my questions,” she said in a recent lecture. “I never thought of them as interviews.”

Art critics as much as artists are shaped indelibly by their moment of entry onto the art scene. Ms. Rose formed her approach at a time when Minimalism was ascendant, and she married one of its key exponents, the artist Frank Stella. With their combined displays of wit, knowledge and slanting opinion, they were a glamorous couple but, according to Ms. Rose, certainly not unflawed.

“We had babies right away,” she told New York magazine, “and everyone in SoHo said, ‘Oh, look, the babies had babies!’”

In her criticism and essays, Ms. Rose took a formalist approach, maintaining that abstract painting is inherently superior to realism. As the decades passed, her faith in connoisseurship came to seem conservative and a rebuff to the present era, in which the meaning of any work of art is deemed inseparable from issues of race and gender.

Even so, Ms. Rose probably did as much as any critic of the postwar era to advance the art careers of women. In 1971, she wrote the first major monograph on Helen Frankenthaler. In 1983, she organized the first museum retrospective of Lee Krasner’s work, a year before Ms. Krasner’s death.

Ms. Rose also furnished the text for definitive monographs on Magdalena Abakanowicz, Nancy Graves, Beverly Pepper and Niki de Saint Phalle, contemporary female sculptors whose work encompassed a gamut of styles.

And although she generally denigrated photography as a lower art form devoid of the imaginative majesty of painting, she wrote a book on the photographs of Carolyn Marks Blackwood after discovering her work in a small-town library show near her summer house in Rhinebeck, N.Y.

“She took me seriously when no one took me seriously, including myself,” Ms. Marks Blackwood said in a phone interview.

Ms. Rose was a vivid personality, a slender blonde with large green eyes, a dimpled smile and a taste for turbans that could rival those of Gloria Swanson. She taught and lectured at several colleges and universities, including Sarah Lawrence, and formed enduring friendships with her students.

The artist Lois Lane, who studied with her at Yale, recalled her astonishment when Ms. Rose materialized at the Willard Gallery in Manhattan and purchased a Lane painting. “Barbara whooshed in there, in true Fairy Godmother style, and that was my first sale,” Ms. Lane wrote in an email. “She has whooshed in so many times over the years.”

Barbara Ellen Rose was born on June 11, 1936, in Washington, the oldest child of Lillian and Ben Rose. Her mother was a homemaker, and her father, who owned a liquor store, had a cut-glass bar made for the family’s recreation room. By the age of 3, Barbara felt aesthetically offended by her “bland, tasteless or vulgar surroundings,” she wrote in a forthcoming memoir, and resolved to flee as soon as she could.

She earned a bachelor’s degree from Barnard and attended graduate school at Columbia, writing her thesis on 16th-century Spanish painting and visiting Pamplona on a Fulbright fellowship. It was the beginning of a lasting fascination with Madrid, where she eventually acquired a home. In 2010, she was awarded the Order of Isabella by the Spanish government for her contributions to Spanish culture.

Ms. Rose was still a student when she started dating Mr. Stella, a precocious Princeton alumnus whose austere black-stripe paintings were pushing art away from the expressionist past. In the fall of 1961 he followed her to Pamplona, sketching in their hotel room as she visited age-old churches to research Navarrese painting.

They were married that October at the register’s office in London. Michael Fried, the formalist art historian, served as a witness and gave them a volume of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s writings as a gift.

Ms. Rose later said that she started writing criticism with Mr. Fried’s encouragement. Her landmark essay “ABC Art,” published in Art in America in October 1965, identified a generation of young artists whose work, she wrote, gave off a “blank, neutral and mechanical impersonality.” They included Mr. Stella, as well as Carl Andre, Robert Morris and Donald Judd. Linking their work to European predecessors like Kazimir Malevich and, less predictably, Marcel Duchamp, she provided a lofty historical lineage for the vanguard art of the ’60s.

Her marriage to Mr. Stella ended in 1969, and they both divorced themselves from their early embrace of Minimalism as well. “The only thing anybody knows about me is that I wrote that article with the title I didn’t give it,” Ms. Rose lamented in Artforum magazine in 2016, referring to “ABC Art.” She blamed her editor for the headline.

In place of reductivism, she championed art that replenished painting with inwardness, subjectivity and lush brushwork. She particularly admired the paintings and prints of Jasper Johns, with his “world of psychologically charged images,” as she wrote in the catalog for “American Painting: The Eighties,” an important group show that she organized in 1979 at New York University’s Gray Art Gallery.

The exhibition included post-Minimalist, imagistic paintings by Ms. Lane, Susan Rothenberg, Bill Jensen, Robert Moskowitz and Gary Stephan, among others, and its grandiose title — it was named for a decade that had yet to begin — was taken by critics as either brilliant prophecy or brazen posturing.

In a time when professional women were often branded as overly ambitious, Ms. Rose endured countless jabs from her male colleagues. “I have been beat up by more people than Hillary Clinton,” she joked in 2016.

Among them was Robert Hughes, the art critic for Time magazine, who described Ms. Rose in his memoirs as “one of the most extreme cases of misplaced self-confidence I have ever come across” — no matter that she proved indispensable when he moved to New York from his native Australia, chaperoning him through the lofts of SoHo and providing him with instant entree to the art scene.

It is true that Ms. Rose could be imperious. In 1981, hired as a senior curator at the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston, she declined to move to Houston or give up her longtime position as the art critic of Vogue. Her stint as a Texas curator ended awkwardly in 1985, after she bemoaned the city’s cultural backwardness in an interview with the magazine Artspace.

Ms. Rose was married four times, including twice to Mr. Du Boff, an economic historian who was both her first and last husband. After her divorce from Mr. Stella, she married the rock lyricist Jerry Leiber, who collaborated with the composer Mike Stoller on hit songs for Elvis Presley, the Coasters and many others. In 2009, she remarried Mr. Du Boff on what was their 50th wedding anniversary.

In addition to him, she is survived by her two children from her marriage to Mr. Stella, Rachel and Michael Stella, and four grandchildren.

In her last decade, though suffering from advanced cancer, Ms. Rose sat at her desk and wrote a memoir, “The Girl Who Loved Artists,” which she had been circulating to publishers at her death. Her characterization of herself as a “girl” might seem coy for a woman whose body of work is marked by a formidable critical voice, but Ms. Rose was full of contradictions.

Her last published article was a review of work by Andrew Lyght, the Guyana-born artist, which appeared in The Brooklyn Rail in October. “The capacity to synthesize opposites is one of the distinctions of his entirely original style,” she wrote. That comment could have applied just as easily to her.

Art

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone – BBC.com

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Ukrainian sells art in Essex while stuck in a warzone BBC.com

Source link

Art

Somerset House Fire: Courtauld Gallery Reopens, Rest of Landmark Closed

The Courtauld Gallery at Somerset House has reopened its doors to the public after a fire swept through the historic building in central London. While the gallery has resumed operations, the rest of the iconic site remains closed “until further notice.”

On Saturday, approximately 125 firefighters were called to the scene to battle the blaze, which sent smoke billowing across the city. Fortunately, the fire occurred in a part of the building not housing valuable artworks, and no injuries were reported. Authorities are still investigating the cause of the fire.

Despite the disruption, art lovers queued outside the gallery before it reopened at 10:00 BST on Sunday. One visitor expressed his relief, saying, “I was sad to see the fire, but I’m relieved the art is safe.”

The Clark family, visiting London from Washington state, USA, had a unique perspective on the incident. While sightseeing on the London Eye, they watched as firefighters tackled the flames. Paul Clark, accompanied by his wife Jiorgia and their four children, shared their concern for the safety of the artwork inside Somerset House. “It was sad to see,” Mr. Clark told the BBC. As a fan of Vincent Van Gogh, he was particularly relieved to learn that the painter’s famous Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear had not been affected by the fire.

Blaze in the West Wing

The fire broke out around midday on Saturday in the west wing of Somerset House, a section of the building primarily used for offices and storage. Jonathan Reekie, director of Somerset House Trust, assured the public that “no valuable artefacts or artworks” were located in that part of the building. By Sunday, fire engines were still stationed outside as investigations into the fire’s origin continued.

About Somerset House

Located on the Strand in central London, Somerset House is a prominent arts venue with a rich history dating back to the Georgian era. Built on the site of a former Tudor palace, the complex is known for its iconic courtyard and is home to the Courtauld Gallery. The gallery houses a prestigious collection from the Samuel Courtauld Trust, showcasing masterpieces from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. Among the notable works are pieces by impressionist legends such as Edouard Manet, Claude Monet, Paul Cézanne, and Vincent Van Gogh.

Somerset House regularly hosts cultural exhibitions and public events, including its popular winter ice skating sessions in the courtyard. However, for now, the venue remains partially closed as authorities ensure the safety of the site following the fire.

Art lovers and the Somerset House community can take solace in knowing that the invaluable collection remains unharmed, and the Courtauld Gallery continues to welcome visitors, offering a reprieve amid the disruption.

Art

Sudbury art, music festival celebrating milestone

Sudbury’s annual art and music festival is marking a significant milestone this year, celebrating its long-standing impact on the local cultural scene. The festival, which has grown from a small community event to a major celebration of creativity, brings together artists, musicians, and visitors from across the region for a weekend of vibrant performances and exhibitions.

The event features a diverse range of activities, from live music performances to art installations, workshops, and interactive exhibits that highlight both emerging and established talent. This year’s milestone celebration will also honor the festival’s history by showcasing some of the artists and performers who have contributed to its success over the years.

Organizers are excited to see how the festival has evolved, becoming a cornerstone of Sudbury’s cultural landscape. “This festival is a celebration of creativity, community, and the incredible talent we have here in Sudbury,” said one of the event’s coordinators. “It’s amazing to see how it has grown and the impact it continues to have on the arts community.”

With this year’s milestone celebration, the festival promises to be bigger and better than ever, with a full lineup of exciting events, workshops, and performances that will inspire and engage attendees of all ages.

The festival’s milestone is not just a reflection of its past success but a celebration of the continued vibrancy of Sudbury’s arts scene.

-

News8 hours ago

B.C. to scrap consumer carbon tax if federal government drops legal requirement: Eby

-

News8 hours ago

A linebacker at West Virginia State is fatally shot on the eve of a game against his old school

-

Sports9 hours ago

Lawyer says Chinese doping case handled ‘reasonably’ but calls WADA’s lack of action “curious”

-

News19 hours ago

Reggie Bush was at his LA-area home when 3 male suspects attempted to break in

-

News9 hours ago

RCMP say 3 dead, suspects at large in targeted attack at home in Lloydminster, Sask.

-

Sports3 hours ago

Canada’s Marina Stakusic advances to quarterfinals at Guadalajara Open

-

News8 hours ago

Hall of Famer Joe Schmidt, who helped Detroit Lions win 2 NFL titles, dies at 92

-

News9 hours ago

Bad weather and boat modifications led to capsizing off Haida Gwaii, TSB says