Science

Biiwaabko Nimosh: Taking us places

|

|

The students of the Wikwemikong High School Science class and robotics team virtually meet NASA mechanical engineer Aaron Yazzie on January 19, 2023.

By Walter Quinlan

WIIKWEMKOONG UNCEDED TERRITORY — Could someone from Wikwemikong High School work at NASA? “Yes, of course, for sure!” replied NASA mechanical engineer Aaron Yazzie when he virtually met with the robotics team and science students this January.

Yazzie is Diné (Navajo) who grew up amongst the canyons and pastel-coloured mesas of northeastern Arizona. He studied at a small-town public school and went to Stanford University on a scholarship.

Since 2008, Yazzie has worked at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, designing mechanical systems for their robotic space search missions. He is part of the team that designed and built “Perseverance” – the Mars Land Rover.

It was a journey with challenges.

“When I left my home to go to Stanford, that was a big culture shock, and I had a lot to learn,” he said. “I sought out study groups, peer groups, and extra time with my professors.”

Yazzie’s story inspired the students.

“It’s not every day that you get to meet someone like Aaron,” said Baybee Bryant. “I like that he kept trying and trying.”

The robotics team from Wiikwemkoong has a proud tradition. Established in 2015, they reached the FIRST Robotics world championships in 2019, winning the prestigious Chairman’s Award.

Every January, FIRST Robotics releases a game worldwide. Teams spend time doing strategic analysis, developing a game plan, and designing and building a robot to effectively play the game.

“These are large-scale industrial robots,” explained Chris Mara, Wikwemikong High School science teacher and robotics team coach. “They weigh 125 lbs and can travel 15 feet per second.”

Wiikwemkoong’s robot is the “Biiwaabko Nimosh” (Iron Dog), named by the grandmother of the first robotics team captain Annie Wemigwans, Julie Wemigwans.

Yazzie and the students found that they have a lot in common.

“The things I do in my job every day are very similar to what they are doing now: design parts and mechanisms,” he said.

The team recently completed their design work for this year’s FIRST Robotics competition. They are now building a robot that must “pick up and place objects on a scale of low, medium, and high difficulty,” said robotics team member Zander Shawongonabe.

“We’re all one team,” said Pahquis Trudeau. “But we work in smaller groups and we all have our specialties.”

Aaron agrees with this approach.

“Engineering isn’t just about being smart at math and science. It’s about being creative, working together on a large team, and becoming a well-rounded leader,” he said.

Teamwork is about problem-solving, too.

“Problems that seem impossible but that the students are working out,” said Aaron, citing electronics as an example.

“There are lots of wires in a big robot,” Zander said.

The idea to bring Aaron to Wiikwemkoong originated with Dominic Beaudry of Science North’s Indigenous Advisory Committee and funding was provided by the Ministry of Education. Matthew Graveline, an outreach staff scientist at Science North, hopes there will be more opportunities for Aaron to visit the north.

This year at Wiikwemkoong, they face a new challenge.

“There are no veterans on the robotics team,” said Mr. Mara.

Still, the team of engineers and scientists can count on a coach proud of their courage and openness to take on any challenge that may come their way.

For Pahquis Trudeau, the robotics team is part of his long-term learning path.

“I want to take mechanical engineering in the future,” he said. “And why not take this opportunity to learn about mechanics and robotics?”

And for Zander Shawongonabe, “the best of all is building the robot. It’s amazing, very cool. It makes me feel like ‘We built that,’ and hopefully, it takes us places.”

Science

Record breaker! Milky Way's most monstrous stellar-mass black hole is sleeping giant lurking close to Earth (Video) – Space.com

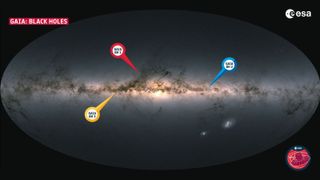

The Milky Way has a big newfound black hole, and it lurks close to Earth! This sleeping giant was discovered with the European space telescope Gaia, which tracks the motion of billions of stars in our galaxy.

Stellar-mass black holes are created when a large star runs out of fuel and collapses. The new discovery is a landmark, representing the first time that a big black hole with such an origin has been found close to Earth.

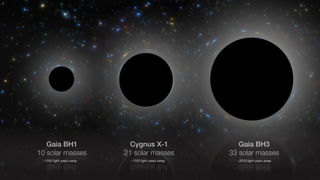

The stellar-mass black hole, designated Gaia-BH3, is 33 times more massive than our sun. The previous most massive black hole of this class found in the Milky Way was a black hole in an X-ray binary in the Cygnus constellation (Cyg X-1), whose mass is estimated to be around 20 times that of the sun. The average stellar-mass black hole in the Milky Way is about 10 times heftier than the sun.

Gaia-BH3 is located just 2,000 light years from Earth, making it the second-closest black hole to our planet ever discovered. The closest black hole to Earth is Gaia-BH1 (also discovered by Gaia), which is 1,560 light-years away. Gaia-BH1 has a mass around 9.6 times that of the sun, making it considerably smaller than this newly discovered black hole.

“Finding Gaia BH3 is like the moment in the film ‘The Matrix’ where Neo starts to ‘see’ the matrix,” George Seabrook, a scientist at Mullard Space Science Laboratory at University College London and a member of Gaia’s Black Hole Task Force, said in a statement sent to Space.com. “In our case, ‘the matrix’ is our galaxy’s population of dormant stellar black holes, which were hidden from us before Gaia detected them.”

Seabroke added that Gaia BH3 is an important clue to this population, because it is the most massive stellar black hole found in our galaxy.

Of course, Gaia-BH3 is a small fry compared to the supermassive black hole that dominates the heart of the Milky Way, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), which has a mass 4.2 million times that of the sun. Supermassive black holes like Sgr A* aren’t created by the deaths of massive stars but rather by mergers of progressively larger and larger black holes.

Sleeping giant black hole caused stellar companion to throw a wobbly

All black holes are marked by an outer boundary called an event horizon, at which point the black hole’s escape velocity exceeds the speed of light. That means an event horizon is a one-way light-trapping surface beyond which no information can escape.

As a result, black holes don’t emit or reflect light, meaning they can only be “seen” when they are surrounded by material that they gradually feed on. Sometimes, this means a black hole in a binary system pulling material from a companion star, which forms a disk of gas and dust around it.

The tremendous gravitational influence of black holes generates intense tidal forces in this surrounding matter, causing it to glow brightly with material that is destroyed and consumed, also emitting X-rays. Additionally, the material the black hole doesn’t feast on can be channeled to its poles and blasted out as near-light speed jets, which are accompanied by the emission of light.

All of these light emissions can allow astronomers to spot black holes. The question is, how can “dormant” black holes that aren’t feeding on gas and dust around them be detected? For instance, what if a stellar-mass black hole has a companion star, but the two are too widely separated for the black hole to snatch stellar matter from its binary partner?

In cases like this, the black hole and its companion star orbit a point that represents the system’s center of mass. This is also the case when a star is orbited by a light companion, such as another star or even a planet.

Orbiting the center of mass results in a wobble in the motion of the star, which is visible to astronomers. Because Gaia is adept at precisely measuring the motion of stars, it is the ideal instrument to see this wobble.

Gaia’s Black Hole Task Force set about looking for odd wobbles that couldn’t be accounted for by the presence of another star or a planet and that indicated a heavier companion, possibly a black hole.

Homing in on an old giant star in the constellation Aquila, located 1,926 light-years from Earth, the team found a wobble in the star’s path. That wobble suggests that the star is locked in orbital motion with a dormant black hole of exceptionally high mass. The two are separated by a distance that ranges from the distance between the sun and Neptune at their widest and our star and Jupiter at their closest.

“It’s a real unicorn,” lead researcher Pasquale Panuzzo of CNRS, Observatoire de Paris in France, said in a statement. “This is the kind of discovery you make once in your research life. So far, black holes this big have only ever been detected in distant galaxies by the LIGO-Virgo-KAGRA collaboration, thanks to observations of gravitational waves.”

Related: What are gravitational waves?

Thanks to the sensitivity of Gaia, the Black Hole Task Force was also able to put constraints on the mass of Gaia-BH3, finding it to possess 33 solar masses.

“Gaia-BH3 is the very first black hole for which we could measure the mass so accurately,” said Tsevi Mazeh, a scientist and Gaia collaboration member at Tel Aviv University. “At 30 times that of our sun, the object’s mass is typical of the estimates we have for the masses of the very distant black holes observed by gravitational wave experiments. Gaia’s measurements provide the first undisputable proof that [stellar-mass] black holes this heavy do exist.”

RELATED STORIES:

However, the Gaia-BH3 system is bound to be of great interest to scientists for more than just its proximity to Earth and the mass of its black hole.

The star in this system is a sub-giant star that is around five times as large as the sun with 15 times its brightness, though it is cooler and less dense than our star. The Gaia-BH3 companion star is mainly composed of hydrogen and helium, the universe’s two lightest elements, lacking heavier elements, which astronomers (somewhat confusingly) call “metals.”

The fact that this star is “metal-poor” suggests that the star that collapsed and died to create Gaia-BH3 also lacked heavier elements. Metal-poor stars are expected to shed more mass than their more metal-rich counterparts during their lives, so scientists have questioned if they can maintain enough mass to birth black holes. Gaia-BH3 represents the first hint that metal-poor stars can indeed do so.

“Gaia’s next data release is expected to contain many more, which should help us to ‘see’ more of ‘the matrix’ and to understand how dormant stellar black holes form,” Seabroke concluded.

The team’s research was published today (April 16) in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Science

Nasa confirms metal chunk that crashed into Florida home was space junk

|

|

A heavy chunk of metal that crashed through the roof of a Florida home is, in fact, space junk, Nasa has confirmed.

The federal space agency said that a cylinder slab that tore through a house in Naples, Florida, last month was debris from a cargo pallet released from the international space station in 2021, according to a Nasa blogpost.

The determination was made after the agency collected the debris from the Florida home and analyzed it at the Kennedy Space Center.

“Based on the examination, the agency determined the debris to be a stanchion from the Nasa flight support equipment used to mount the batteries on the cargo pallet,” the agency said.

The pallet, which contained ageing nickel hydride batteries, was released after new lithium-ion batteries were installed in the space station.

The debris was supposed to be destroyed in the Earth’s atmosphere. Instead, a piece of metal crashed through a Florida home, NBC News reported.

The debris weighs 1.6lb and measures about 4in by 1.6in.

Homeowner Alejandro Otero described the experience to WINK News, which first reported the story.

“It was a tremendous sound. It almost hit my son. He was two rooms over and heard it all,” Otero said to WINK.

“Something ripped through the house and then made a big hole on the floor and on the ceiling.”

The scientific journal Ars Technica previously speculated that the metal was probably space station debris. Nasa finally confirmed the origin of the chunk on Monday.

The space agency added that it would investigate how the debris managed to survive its re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere and “update modeling and analysis”.

It is unclear if Nasa will cover the cost of damages to Otero’s home.

In comments posted to X shortly after the incident, Otero said that Nasa had not responded to messages he left with the agency.

Science

Federal government announces creation of National Space Council – CBC News

Canada’s space sector received a boost from the federal government in its budget, both in terms of money and vision.

The 2024 budget included a proposal for $8.6 million in 2024-25 to the Canadian Space Agency (CSA) for the Lunar Exploration Accelerator Program (LEAP), which invests in technologies for humanity’s return to the moon and beyond.

In addition to the funding, the federal government also announced the creation of a National Space Council, which will be “a new whole-of-government approach to space exploration, technology development, and research.”

For Space Canada, an organization comprised of roughly 80 space sector companies including some of Canada’s largest, such as Magellan Aerospace, Maritime Launch and MDA, it was a welcome announcement.

“We’ve been advocating for it since the inception of our organization, and we were really very happy, and we applaud the federal government’s commitment announced in the budget,” said Brian Gallant, CEO of Space Canada.

Gallant said that investment in space is an investment in Canada.

“Two-thirds of space sector jobs are STEM jobs. These are good paying solid jobs for Canadians. And on top of that, we have approximately $2.8 billion that is injected into the Canadian economy because of the space sector,” he said.

The U.S. formed its National Space Council in 1989, but it was disbanded in 1992 and reestablished in 2017.

In the 2023 budget, the government announced proposed spending of $1.2 billion over 13 years, that was to begin in 2024-25, to the CSA’s contribution of a lunar utility vehicle that would assist astronauts on the moon. The as–yet–developed vehicle could help astronauts move cargo from landing sites to habitats, perform science investigations or support them during spacewalks on the surface of the moon.

It also proposed to invest $150 million over five years for the LEAP program.

MDA, the company behind Canadarm, was also pleased with the announcement.

“Canada has an enviable global competitive advantage in space and the creation of a National Space Council is critical to Canada maintaining that leadership position,” CEO Mike Greenley said in an email to CBC News.

“Space is now a rapidly growing, highly strategic and competitive domain, and there is a real and urgent need to recognize its importance to the lives of Canadians and to our economy and national security.”

The next project for MDA is Canadarm3, which will be part of Lunar Gateway, a international space station that will orbit the moon. It will serve as a sort of jumping-off point for astronauts heading to the moon and eventually beyond.

“The Lunar Gateway is a great opportunity for Canada and for MDA Space to not only provide the next generation of Canadarm robotics but to clearly plant our flag as a core national and industry participant in the Artemis era,” Greenley said.

Lunar Gateway is set to begin construction no earlier than 2025, according to NASA.

-

Sports21 hours ago

Sports21 hours agoTeam Canada’s Olympics looks designed by Lululemon

-

News22 hours ago

Richard Chevolleau Short Film “Marvelous Marvin” Set to go to Camera

-

Business20 hours ago

Firefighters battle wildfire near Edson, Alta., after natural gas line rupture – CBC.ca

-

Investment23 hours ago

Investment23 hours agoStephen Poloz will lead push to boost domestic investment by Canadian pension funds

-

Tech13 hours ago

Tech13 hours agoiPhone 15 Pro Desperado Mafia model launched at over ₹6.5 lakh- All details about this luxury iPhone from Caviar – HT Tech

-

Art23 hours ago

Richmond art exhibits travel back in time, explore legacies

-

News23 hours ago

Federal budget 2024: Some of the winners and losers

-

Sports13 hours ago

Sports13 hours agoLululemon unveils Canada's official Olympic kit for the Paris games – National Post