It seems that neither doctors nor patients are happy with today’s medical care system.

Nicholas Pimlott, an academic family physician, recently described in The Globe and Mail the prevailing sadness and feelings of failure of doctors, especially family doctors, with their working lives. Tracey Lindemann, in the same section of the newspaper and on the same day, described her repeated disappointment in the contact with doctors, over a long period of 24 years, who denied her reality of severe and recurrent monthly pain.

Lindemann, a journalist and author of Bleed: Destroying Myths and Misogyny in Endometriosis Care, was told that her agony was a normal part of being a woman and that she should exercise, lose weight and take birth control pills. These things did not work. And the gaslighting by doctor after doctor made the physical pain only a part of her suffering. Eventually, Lindeman found a doctor with the necessary expertise who used ultrasound technology and diagnosed her with Stage 4 endometriosis. She questions why, when about 5 per cent of women or 400 million globally are estimated to have endometriosis, it was so difficult to diagnose; why, for all those years, she felt she was to blame for her suffering.

Pimlott reports that feelings of sorrow and a sense of failure are experienced by many physicians, especially family doctors. He argues that part of the problem is the amount of paperwork that is now necessary curtails the amount of time a doctor can spend with and connecting to a patient. If doctors had more time to listen to their patients and to understand their symptoms, things would be better, he says. Over Pimlott’s career, the amount of required paperwork has tripled, and disappointingly, he is thus only able to see a fraction of the patients he was once able to see.

But, Pimlott adds, the discontent amongst doctors was longstanding both before and after the prodigious paperwork requirements. Pimlott attributes some of the sadness to the “bogus contract” between doctors and patients. This contract includes four expectations of doctors: (1) that modern medicine can do incredible things and solve all problems; (2) that doctors can essentially see inside the bodies of their patients and know what is wrong; (3) that doctors know everything needed for helping and healing; (4) and that doctors can even fix social problems. In return, patients accord high incomes and social status to physicians.

Doctors understand they cannot solve all problems, perhaps most especially social problems such as poverty and the disease it begets.

But doctors know there are limits to their knowledge, and so the contract is spurious. It does not work. Doctors understand they cannot solve all problems, perhaps most especially social problems such as poverty and the disease it begets. On the other hand, doctors do know how hard medical work can be and how easily mistakes can be made. They realize there is a fine line between doing good and doing harm. Finally, Pimlott states, doctors do not spill the beans about this huge gulf between the views of patients and their own for fears of losing income and disappointing patients.

Clearly, this “bogus contract” points to a misfit between what doctors have come to understand as their job and what patients expect of them. However, we also should acknowledge that before they became doctors, doctors were patients. They, too, were members of the public. It is likely, therefore, that they held the same views as the public before medical school. Furthermore, it is highly probable that many, if not most, entered medical school with the idea that they would be able to do good and to help their patients in one way or another. Doctors have had then to suffer the anguish of not being able to do what they had hoped.

But where does this crushing contract come from? Why is it maintained despite the grief it causes for both patients and for doctors whose hopes are dashed by the realities of medical care.

I would suggest it arises out of a complex and multi-layered social, economic and political process in which conventional medical treatments are over-valorized and emphasized at the expense of intervention in the social and economic causes of ill-health. The social determinants of health include various interventions meant to diminish poverty and increase equality. Instead, we focus on medical expenditures.

This over-emphasis on medicine is sometimes called medicalization and is omnipresent in the modern world. It is found in the mounting sway of medicine to define the terms of engagement with routine daily life, such as antidepressants for moods and medication for weight loss.

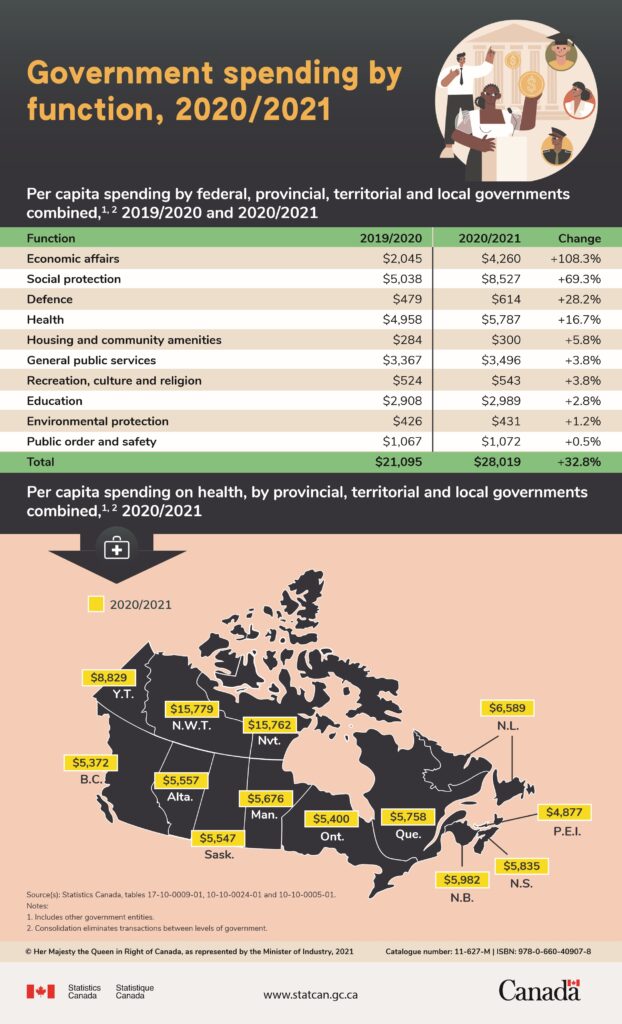

It happens when more of everyday life is thought to be germane to medical research and practice, such as watches that constantly measure heart rate, stress level, blood oxygen level and so forth. It represents a growth in diagnostic categories of illnesses, including mental illnesses and chronic conditions due to our longer lifespans. And it contributes to a sense of disappointment for patients who expect too much of their doctors and of failure for doctors who cannot keep up with these growing demands. The following table illustrates my point.

Before the pandemic, we were spending $4,950 on average per person on health but only $2,908 on education and $426 on environmental protection. Repeated research has demonstrated that both education and well-maintained parks protect health.

We are underwriting the “bogus contract” by this over-emphasis on the power of medicine. At the same time, we are ignoring the relative importance of the precursors to good health.