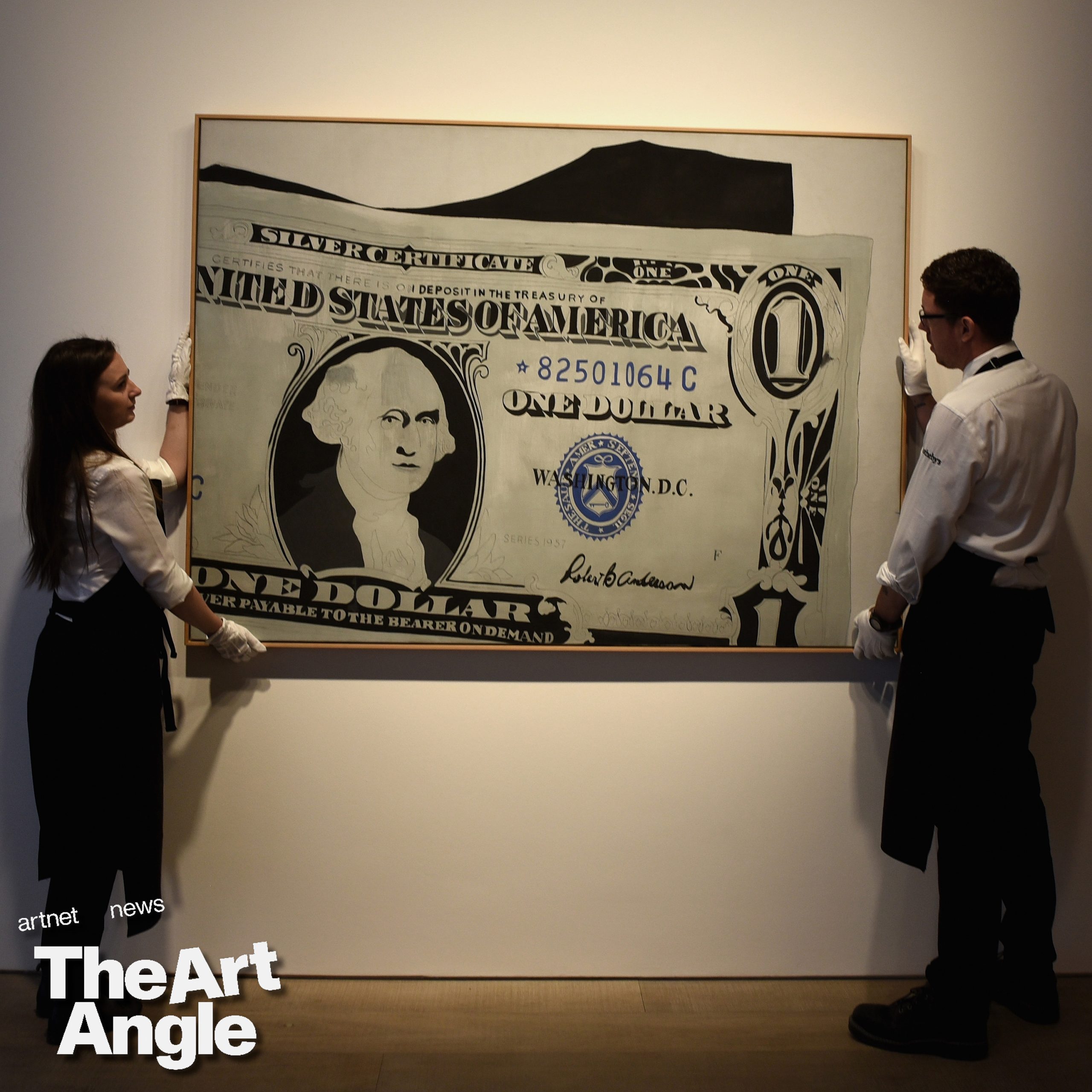

Several works on view at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

|

|

I think public art is propaganda, frankly.

~Hank Willis Thomas, 2019

In 2019, Brooklyn-based multimedia artist Hank Willis Thomas was awarded a commission to create a sculpture celebrating the civil-rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. The monument was to be installed on Boston Common, America’s oldest public park, where King gave a speech to a crowd of 22,000 people in April 1965. Thomas was among five finalists out of 126 applicants whose work was reviewed by a committee convened by the City of Boston and the non-profit Embrace Boston. The non-profit’s stated mission is “to dismantle structural racism through our work at the intersection of arts and culture, community, and research and policy.” In the section dedicated to “arts and cultural representation” this goal is further specified as:

Activate arts and culture to reimagine and recast cultural representations of language, images, narratives, and cognitive cues to interrupt and reimagine the public’s conventional wisdom about race in which White privilege and racial disparities are perceived as normal and disconnected from history and institutions. [emphasis in original]

At first glance, the sculpture made possible by Embrace Boston, also serendipitously titled ‘The Embrace,’ seems perfect for recasting cultural representations. The monument is based on a 1964 photo of a celebratory hug shared by King and his wife after he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. Had Hank Willis Thomas gone down the well-trotted path of figuration—providing a portrait likeness of his subjects—‘The Embrace’ would have been treated as any other dignified public sculpture project, garnering complimentary mentions and perhaps some accolades, that rubbed off the memory of MLK onto his bronze avatar. But the artist, who came to sculpture from photography, and whose other work emphasizes concept over form, chose an approach that eschewed figuration. The Boston sculpture presented emblematically posed, disembodied extremities (no heads, no torsos) intended to convey an idea not through representation, but through a symbol of love.

Hank Willis Thomas had already tested this model, most recently in ‘Unity’ (2019)—a pedestal-less, bronze, 20-foot-tall arm, amputated across its rotator cuff and planted on the cement divider at the foot of the Brooklyn Bridge, its index finger raised to the sky. It has been favorably received. The latest 20-foot-tall monument, which reportedly cost $10m of private funding, was finally unveiled on January 13th, in front of local dignitaries and MLK’s son Martin Luther King III. While the reaction on the scene was celebratory, social media erupted with a panoply of jokes, most of which zeroed in on the sexual associations prompted by the tangle of intertwining limbs.

In 2019, Hank Willis Thomas unveiled “Unity,” a sculpture in @DowntownBklyn commissioned by our #PercentforArtNYC program. Towering bronze sculptures, “The Embrace” and “Unity” both personify the incredible impact of solidarity and community empowerment. pic.twitter.com/cb3wrgFrBH

— NYC Cultural Affairs (@NYCulture) January 16, 2023

The uproar was impossible to ignore. The website Hyperallergic—a bastion of progressivism—ran an article titled, “The New MLK Sculpture Is Officially a Meme,” highlighting noteworthy responses from Twitter and TikTok. The sculpture was also the subject of a brutal routine by the comedian Leslie Jones on The Daily Show:

Many other commentators also noticed the sculpture’s unmistakable (and surely unintended?) sexual imagery, pointing out that it resembled an engorged penis held by dainty female hands and/or cunnilingus performed by a bald man, but they were not amused nor did they mean to be amusing. The Washington Post columnist Karen Attiah posted a string of searing tweets, calling out those behind the sculpture for reducing King and his wife to body parts and grossly distorting “his radicalism, anti-capitalism, his fierce critiques of white moderates” in a “whitewashed symbol of love.” She followed up her thread with a strongly-worded opinion piece in which she described the sculpture as a “half-assed banalit[y] in the name of ‘social justice.’”

It doesn’t sit well with me that Martin Luther King and Coretta Scott King are reduced to body parts– just their arms. Not their faces- their expressions.

For such a large statue, dismembering MLK and Coretta Scott King is… a choice. A deliberate one. pic.twitter.com/Asi0SCHtPg

— Karen Attiah IS ON INSTAGRAM @karenattiah (@KarenAttiah) January 16, 2023

The following day, Coretta Scott King’s cousin, Bay Area activist and community organizer Seneca Scott, took the condemnation a step further in an article titled “Masturbatory ‘Homage’ to My Family.” Referring to the sculpture as a “major dick move (pun intended) that brings very few, if any, tangible benefits to struggling black families,” he derided it as “performative altruism” meant to “represent black love at its purest and most devotional.” This, he argued, played into a “classist and racist … woke algorithm.” Far from being a proper celebration of an icon, “this sculpture is an especially egregious example of the woke machine’s callousness and vanity.” For Scott, the disembodied, sexually suggestive bronze unveiled on Boston Common was yet another example of blaxploitation.

All this criticism arises from the simple fact that the monument is visually unintelligible. While Thomas’s 2019 ‘Unity’ benefits from the intrinsic likeness of a vertically placed human limb to the time-honored obelisk shape, ‘The Embrace’ is fundamentally confusing. It is not easily legible, forcing the viewer to deduce meaning in the absence of relevant components (such trifles as heads and faces). Its references are muddled. It takes for granted the premise of Gestalt psychology, which states that the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. ‘The Embrace’ certainly does not make it easy to get past the parts.

If the German psychologists who formulated the principles of Gestalt were correct, if our minds do indeed have a tendency to rely on visual clues to interpret an image, then formal clarity and cohesion become paramount. Otherwise, we end up with an interpretational free-for-all, a Rorschach test that allows the audience to exercise their debauched imaginations. In a television interview addressing public response to the sculpture, Thomas himself brought up the idea of the sculpture as a Rorschach test. He suggested that the audience’s collective mind is in the gutter, but failed to acknowledge his responsibility for the visual ambiguity that caused the reaction. It is the sculptor’s job to design a work that enables viewers to deduce its overarching meaning, without ending up in interpretational cul-de-sacs.

Consider two historic examples of successful sculpture that share meaning (love) and appearance (the organic shape) with ‘The Embrace.’ The first is an intimately sized (under two feet) limestone carving by the French-Romanian sculptor Constantin Brancusi. ‘The Kiss’ (1916) shows a naked man and a woman locked in an amorous embrace. The front of their faces and their mouths are hidden from view. Their respective genders are identifiable only by the relative lengths of their hair and the female figure’s flattened breasts.

The lovers’ anatomically improbable square profiles, complete with half-exposed stylized eyes, merge into a single frontal view, making the idea of the embrace, and the kiss itself, unambiguously central. Indeed, Brancusi’s little sculpture would make a splendid symbol of Unity Through Love.

The second example is the ‘Recumbent Figure’ (1938) by the English sculptor Henry Moore. Carved from stone mined in Oxfordshire, this mid-size sculpture, which represents a female nude, reinforces the idea of an organic mass through the way the body is posed, its resemblance to bleached bones and skulls, the rounded shapes of Moore’s native landscape, and modernist nods to both ancient and indigenous predecessors. Its overarching message of natural harmony uncorrupted by technology supersedes the separate visual components.

As in the case of Brancusi, the dirtiest of minds would struggle to come up with an obscene reading. Both sculptures make self-evident the ideas they visually represent.

Unlike these two works, however, ‘The Embrace’ is a muddle of the inexplicable. It is selectively representational, showing isolated hugging arms cropped from a photograph in which the facial expressions were central. The chart of the arms is meaningless without the legend needed to explain the nature of the hug (support, pride, joy), and this opens the awkward tangle to arbitrary interpretation. In the absence of heads and faces, the arms retain sartorial identification—a bracelet on the bare forearm of Coretta Scott King and the shirt and suit of the arm of the MLK. But this only further lends the sculpture to sexualized readings, prompted by a slender female arm supporting a plump, elongated male appendage, and turns what was intended to be a respectful work into a bad joke.

It also makes the sculpture visually proximate to an intentionally humorous work by the Los Angeles-based veteran of conceptual art, Paul McCarthy. In 2007, McCarthy created a monumental, multi-part, inflatable sculpture that realistically represented a large pile of excrement. Appropriately titled ‘Complex Shit’ (later demurely renamed ‘Complex Pile’), it was McCarthy’s commentary on public sculpture’s tendency to pretension.

‘Complex Shit’ garnered additional notoriety in July 2008, when its original incarnation, on display at the Paul Klee Center in Berne, was caught in a strong gust of wind and carried over 200 meters, landing on the grounds of a children’s home. For someone making a public sculpture in the late 2010s, it must have taken some chutzpah (or ignorance of conceptual sculpture) to attempt a bronze, organically shaped, multi-part monumental form and assume they would escape association with McCarthy’s shit.

Are these multiple formal shortcomings the result of ineptitude? Hard to say. It may just be a case of misplaced priorities. In an Artnet interview from the summer of 2020, Thomas argued for the unreserved inclusivity of an artist’s self-designation: “Well, I think we’re all artists.” Which makes his following statement about not appreciating or respecting art until “about the age of 30 … by that time I already had a BFA and an MFA” either disingenuous or seriously misguided. It is hard to imagine a successful application for a Batchelor of Fine Arts, not to mention a Master of Fine Arts degree, which openly admits the applicant’s lack of appreciation or respect for art.

Meanwhile, Thomas’s relationship with progressive politics is unambiguous. In response to a question about “changing unjust institutions with non-art work,” he describes founding a Super PAC (later a non-profit called “For Freedoms”) as a way “to promote the critical work artists are doing by framing political speech, because we know that when you say something is ‘political’ it implies there’s something at stake.” In other words, politicization is a public relations strategy. Asked whether he would entertain the idea of going into politics, Thomas responds: “I think anyone who cares at all should consider it. I would hope that I am not the only artist who’s seriously considering it, and will probably at some point try to run for some office.” It is surely a better stratagem to enter politics directly, rather than attempt to create a space for politics in art. Otherwise, we end up with boring art and impotent politics.

This was precisely the argument advanced nearly half-a-century ago by the influential New York art critic Clement Greenberg. In a 1976 lecture to a packed room of artists and students in London, Greenberg brought up the (then) current fashion for politically committed art. In his view, prioritizing political content over form tended to diminish the quality of the work. Art, he argued, was being taken “in the direction where presumably taste could not follow … where the eye could not follow…” This point was consistent with Greenberg’s position that the source of art’s power is its “self-critical” quality, whereby each medium is expected to function according to its own unique method (painting is distinguished by its flatness, for example).

According to Greenberg, when the content takes over, and the medium loses its purity, the result is a paltry artwork that could only fool an audience outside its respective field:

You wrote bad prose, but you’re read by artists who could not tell the difference between good and bad prose, you wrote incoherently, but you are not being read by logicians, you did a pastiche of philosophical language, but you are not being read by philosophers.

Greenberg’s assertion that a failure to distinguish categories is detrimental to both art (the form) and the political message (the content) is very much applicable to our current predicament. Foreshadowing the mockery elicited by the representational ineptitude of ‘The Embrace,’ the critic pointed out: “It’s very easy to make fun of these things because they to be deserved to be made fun of, and it’s very easy to laugh at them because they deserved to be laughed at, because they are so boring.” In his view, art and politics simply do not mix, and attempts to force them together reduce the efficacy of both.

What should politically active artists do then? Greenberg expanded on his position in the Q&A session, where he encouraged a direct engagement with politics outside of one’s art:

When you are making an art, you are trying to make good art, just as when you are making a screwdriver, you are trying to make a good screwdriver. If you care about what’s happening in the world, you don’t retreat to your studio and try to make art, you go out and try do something about it. […] What I infer from what you said about those people caring what happens outside your studios, outside of art galleries, outside museums, outside art … if you care about these things, you go outside and try to do something about it, if you care enough.

The artist’s mandate is to make art driven by aesthetic concerns, not political aspirations: “Most of us, we care some, but we are supposed to make screwdrivers, so we make screwdrivers … and we don’t have time left for anything except to join a trade union … or maybe go on strike. We certainly don’t do social work.” And while Greenberg recognized that “there are more important ends in life than art” he maintained that an artist’s only aspiration should be to “make the best art.” As a writer himself, Greenberg believed his energy was best spent on writing, not social activism: “the world is full of pain and something that should be done about it. I am not doing a damn thing about it, and I am not proud about that, but I choose not to do anything about it because I only have one life to live. And don’t find it interesting to go out there and help the suffering and the poor.”

Greenberg positively flaunted his lack of political commitment. His anachronistic rational egotism allowed him to embrace his self-interest openly, but his self-interest was in being a writer and not a social worker, as he put it. Such an uber-formalist attitude would not pass muster in today’s art world. Political neutrality is no longer a viable option. Yet, the critic got one thing right when he refused to reduce art to agitprop. In response to further probing, Greenberg bluntly stated that those who make political art “contribute neither to politics, nor to art … neither politics nor art have received anything from the elucubrations of these people.”

The furor around ‘The Embrace’ seems to support Greenberg’s case, but this time the judgment does not come from the ivory tower, but from the audience pit. The wider public—with its innate suspicion of the art world’s insider trading and the baffling price tags of public sculpture—can be relied upon to voice their opinion that the screwdriver they were presented with on Boston Common is no good, and their feedback turned a monument to one of the 20th century’s greatest men into a meme. The public’s response is genuine, heartfelt and—given its provenance—cannot be blamed on elitism. The vox populi’s verdict will stand because, as Thomas correctly stated in his 2020 interview: “Public space belongs to the public and they should have a say in what kinds of images and objects represent the society.” The 20-foot-tall Rorschach test that is ‘The Embrace’ proves that our society, for all its faults and shortcomings, is not ready to be represented by a meme. At least not yet.

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

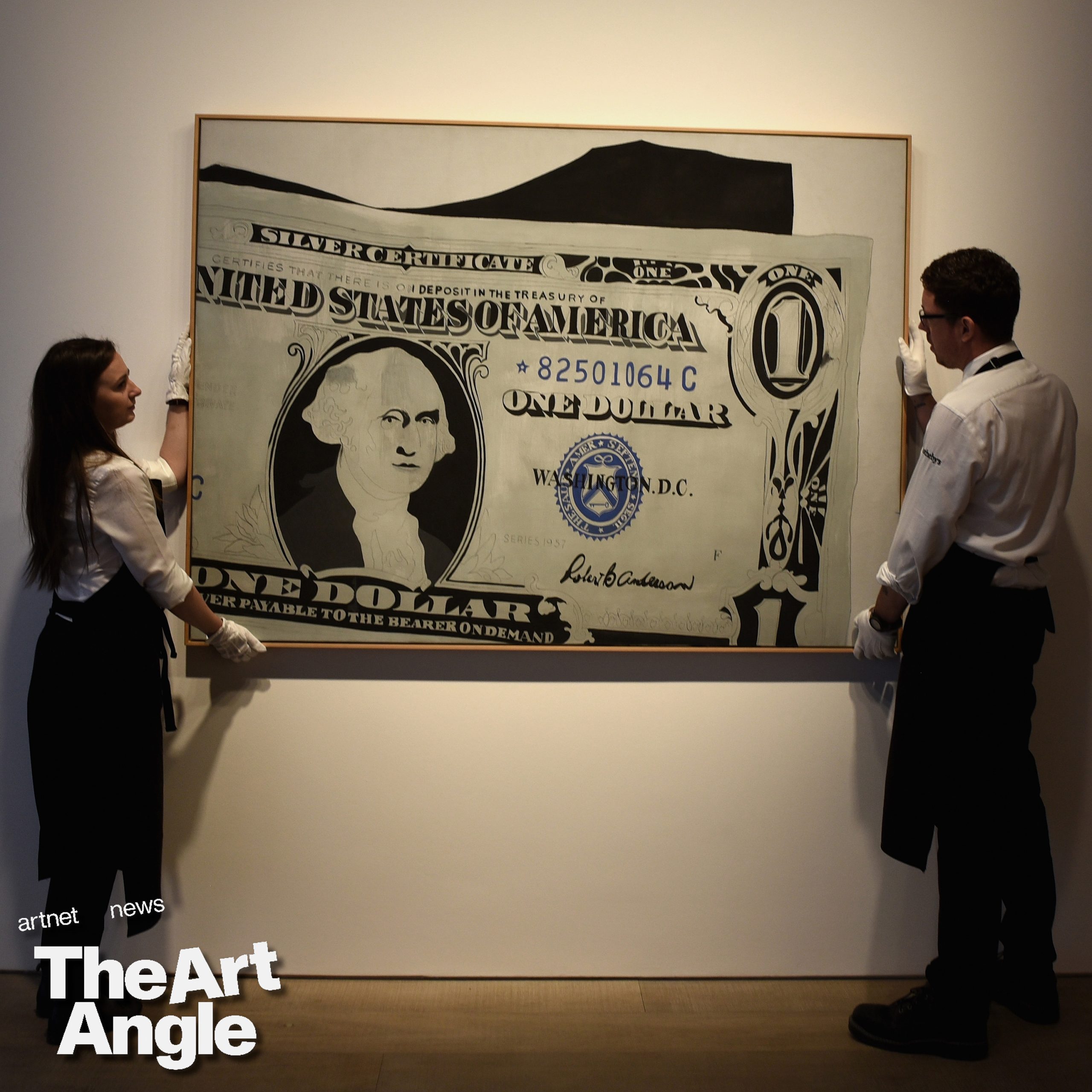

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Digital artist Sam Spratt is living the artist’s dream. This week, he celebrated the opening of “The Monument Game,” his first-ever art show. But it wasn’t a group show in some DIY space in New York, where he is based, like so many artists typically start out, but a solo exhibition in Venice, during the art world’s biggest event of the year—the Venice Biennale. How did Spratt–a virtually unknown name in the art world–make such a tremendous leap? With a little help from his friends, of course, including Ryan Zurrer, the venture capitalist turned digital art champion.

“Something the capital ‘A’ art world doesn’t recognize is the power of the collective, it sometimes leans into the cult of the individual,” Ryan Zurrer told ARTnews during a preview of the opening. “But this show is supported by the entire community around Sam.”

Spratt’s Venice exhibition was put on by 1OF1 Collection, a “collecting club” set up by Zurrer to nurture digital artists working in the NFT space. Since its launch in 2021, 1OF1 has been uniquely successful in bridging the gap between the art world and the Web3 community. Last year, 1OF1 and the RFC Art Collection gifted Anadol’s Unsupervised – Machine Hallucinations – MoMA to the museum, after nearly a year on view in the Gund Lobby. Zurrer also arranged the first museum presentations of Beeple’s HUMAN ONE, a seven-foot-tall kinetic sculpture based on video works, showing it first at Castello di Rivoli in Italy and the M+ Museum in Hong Kong, before sending it to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Arkansas.

With “The Monument Game,” Zurrer is once again placing digitally native art at the center of the art world. While Anadol and Beeple had large cultural footprints prior to Zurrer’s patronage, Spratt is far earlier in his career. But, what attracted Zurrer, he said, was the artist’s shrewd approach to building a dedicated, participatory audience for his work. He did so by making his art a game.

“When I first started looking at NFTs, I spent a long time just figuring out who the players were,” Spratt told ARTnews. “The auctions were like stories in themselves, I could see people’s friends bidding, almost ceremonially, to give the auction some energy, and then other people would come in, and it would get competitive, emotional.”

Spratt released his first three NFTs on the platform SuperRare in October 2021. The sale of those works, the first from his series LUCI, was accompanied by a giveaway of a free NFT to every person who put in a bid. Zurrer had been one of those underbidders (for the work Birth of Luci). While Spratt said the derivative NFTs were basically worthless, he wanted to give something back to each bidder. Zurrer, and others it seems, appreciated the gesture and Spratt quickly gained a following in the Web3 space. The offerings he gave, called Skulls of Luci, became Sam’s dedicated collectors that now go by The Council of Luci. 47 editions were given out and Spratt held back three.

All the works from LUCI are on view at the Docks Cantiere Cucchini, a short walk from the Arsenale, past a rocking boat that doubles as a fruit and vegetable market and over a wooden bridge. Though NFTs typically bring to mind glitching screens and monkey cartoons (ala Bored Ape Yacht Club), the ten works on view depict apes in a detailed, painterly style and emit a soft glow. Taking cues from photography installations, 1OF1 ditched screens in favor of prints mounted on lightboxes.

“We don’t want it to look like a Best Buy in here,” said Zurrer.

Several works on view at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

Each work represents a chapter in a fantasy world that Spratt dreamed up. Though there’s no book of lore to refer to, there seems to be some Planet of the Apes story at play in which an intelligent ape lives alongside humans, babies, and ape-human hybrids. Spratt received an education in oil painting at Savannah College of Art and Design and he credits that technical training with his ability to bring warmth and detail to the digital works. He and the team often say that his art historical references harken to Renaissance and Baroque art, though the aesthetics—to my eye—seem to pull from commercial illustration and concept art. That isn’t too surprising given that this was the environment that Spratt started off in after graduating SCAD in 2010.

“After school I was confronted with the reality that for a digital artist the only path was commercial,” Spratt said.

He did quite well on that path, producing album covers for Childish Gambino, Janelle Monae, and Kid Cudi and bagging clients like Marvel, StreetEasy, and Netflix. Spratt also enjoys a huge audience of fans who have followed him as he’s migrated from Facebook to Tumblr to Twitter and Instagram, posting his hyper-realistic fan-art on each platform. Despite the apparent success, Spratt spoke of the work with bitterness.

“I was a gun for hire. A mimic, hired to be 30% me and 70% someone else,” he said.

Spratt’s personal life blew up when he turned 30 and he traced some of the mistakes he made in his relationships with the fact that he had spent so much of his career “telling other people’s stories.” NFTs seemed like a way out of commercial illustration and a way into an original art practice.

For his latest piece in the LUCI series, Spratt digitally painted a massive landscape set in this ape-human world titled The Monument Game. For the piece, Spratt initially sold NFTs that would turn 209 collectors into “players” (since another edition of 256 NFTs was given to the Council to “curate” new champions”). Each player would then be allowed to make an observation about the painting. The Council of Luci would vote on which three observations were best, and those three Players would receive one of the Skulls of Luci NFTs that Spratt held back. By creating these tiers of engagement, with his Council and player structure, Spratt pushes digital collectors to give the kind of care to his work that more traditional collectors do.

A work at “Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Image courtesy 1OF1. Photography by Anna Blubanana studio.

“Jeff Koons said that the average person looks at a work of art for twenty seconds,” Lukas Amacher, 1OF1’s Artistic Director and the curator of the show, told ARTnews. “Sam has found a way to get people to engage in his work for much longer.”

The game Spratt has designed for the Venice exhibition might seem too gamified to fit the art world’s notion of art, but as Amacher and Zurrer suggest, in the Web3 environment, value is built by finding alternative ways to create investment and attention in what are typically immaterial digital artifacts. And it’s working. Thus far, the LUCI series has generated $2 million in primary sales and about $4 million in additional secondary volume. The challenge now, as it has been for the past three years, is to see if art’s gatekeepers will take this work seriously.

At the presentation of The Monument Game in Venice, an observation deck, built by platform Nifty Gateway, sits in front of the mounted work. Participants can click on the painting on the screen and write down their observations of the work in front of them, no NFT required. The first observation came from star curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, the director of Castello di Rivoli and curator of Documenta 15: a tribute to art dealer Marian Goodman. The second was from Zurrer. Who’s next?

“Sam Spratt: The Monument Game” is on view until June 21 at the Docks Cantiere Pietro Cucchini in Venice.

Take in improv comedy, art discussions and shows, locally-produced theatre and live instrumental or choral music.

Unseasonable snow this week isn’t slowing the arts down; nor should it hamper the enjoyment of events around town. Get out and take in a variety of comedy shows, art exhibitions and theatre this weekend.

1 — Laugh along with the Soaps

Article content

Saskatoon Soaps Improv Comedy presents We Love the ’90s. Return to the 1990s improv-style, complete with flannel, grunge and gangsta rap jokes coming faster than the old dial-up internet connection. The troupe performs live comedy based on audience suggestions, so be prepared with your classic references and ideas. The all-ages show is Friday at the Broadway Theatre at 8 p.m. Learn more at broadwaytheatre.ca.

Advertisement 2

Article content

2 — Chat with a local artist and take in an exhibition

The Ukrainian Museum of Canada presents an artist talk by its second artist in residence, Amalie Atkins. The Saskatoon-based artist discusses her residency and how her creative expression resonates with the history of Ukrainian heritage. The free event is Saturday at the museum at 3 p.m. Atkins’s exhibition will be on display through May 18. Learn more at umcnational.ca.

GlassArt showcases glasswork by members of the Saskatoon Glassworkers Guild. The annual show features unique works made through a variety of processes and techniques. Artists are in attendance and there will be some demonstrations. The exhibition runs Friday through Sunday in the Galleria at Innovation Place. Learn more at saskatoonglassworkersguild.org.

3 — Experience live, local theatre

Live Five Independent Theatre presents Bat Brains (or let’s explore mental illness with vampires), a new comedy by Sam Kruger and S.E. Grummett. Inspired by a months-long mental breakdown, the dark comedy follows Scud the vampire, who hasn’t left his house in 53 years. The arrival of an unexpected visitor launches Scud on a journey through his home, his mind and beyond. The show opens Friday and runs to April 28 at The Refinery. Learn more at ontheboards.ca.

Advertisement 3

Article content

4 — Sing along with a local choir

The Saskatoon Men’s Chorus presents the spring concert, Meetin’ Here Tonight. Enjoy gospel and classic favourites with special guests: bassist Bruce Wilkinson, baritone Adam Brookman and the Outlook Men’s Chorus. Sunday at Zion Lutheran Church at 2:30 p.m. Learn more at saskatoonmenschorus.ca.

Cecilian Singers present their spring concert, Come Sing with Me. The singers are joined by three guests: soprano Kelsey Ronn, violinist Wagner Barbosa and percussionist Darrell Bueckert. The concert is Sunday at Grosvenor Park United Church at 3 p.m. Learn more at ceciliansingers.ca.

5 — Listen to historic instruments

The University of Saskatchewan presents Rawlins Piano Trio, the final concert of the season in the Discovering the Amatis series. The chamber music performance features violinist Ioana Galu and cellist Sonja Kraus from the piano trio. They are joined by flutist Joey Zhuang and violinist Véronique Mathieu. Showcasing the historic Amati string instruments, the concert is Sunday at 3 p.m. in Convocation Hall at the U of S. Learn more at leadership.usask.ca.

Recommended from Editorial

With some online platforms blocking access to the news upon which you depend, our website is your destination for up-to-the-minute news, so make sure to bookmark thestarphoenix.com and sign up for our newsletters here so we can keep you informed.

Article content

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

Type 2 diabetes is not one-size-fits-all: Subtypes affect complications and treatment options – The Conversation

DJT Stock Jumps. The Truth Social Owner Is Showing Stockholders How to Block Short Sellers. – Barron's

How the NHL moved the Arizona Coyotes to Salt Lake City – Sportsnet.ca

Former Bay Street executive leads push to require firms to account for inflation in investment reports – The Globe and Mail

$93 Billion Real Estate Giant Is Betting The Market Is About To Hit Rock Bottom – Yahoo Finance

Comments