Art

Cambodia is an inspiration for the healing power of art after a crisis – The Conversation CA

Even though history has seen different disasters and humanitarian crises, one fact remains: we try to understand what is happening by seeing how others coped, comparing our reaction to theirs. These comparisons allow us to shed light on the best practices for managing or emerging from a crisis.

We note with the COVID-19 pandemic that there is not one response to crises, but many responses that are adapted and implemented through trial and error.

At the Canadian Research Institute on Humanitarian Crisis and Aid our team was interested in a few examples where art and culture have been used to encourage development at the social, community, economic and civic level in various countries, including Haiti and Cambodia.

Cambodia is a special case. It was able to use art and culture to find a way to rebuild itself after the genocide that began in 1975 and ended with the fall of the Pol Pot regime in 1979. While the context is different, is there a way we can draw inspiration from the Cambodian example to recover from the current health crisis?

Art and culture in crisis

First of all, what do we mean by “crisis?” Are we simply referring to the health aspect?

Our government decision-makers have categorized the current period as a “war” against an invisible enemy. But a war leaves after-effects that are not only structural but social, societal and humanitarian as well. Also, as in armed conflicts, this “health war” has imposed a front line in hospitals and seniors’ residences.

In times of war, art and culture, which are important pillars of our societies, are hit hard and sometimes even strategically destroyed.

The rebirth of art in Cambodia

Cambodia has a long and rich history dating back to before the Middle Ages. It was during the golden age of the Khmer Empire (between the ninth and 13th centuries) that arts and culture became integrated into society through religion, rites and customs.

However, for recent generations, this rich Cambodian culture with its oral tradition was greatly affected by the genocide under the tyrannical Khmer Rouge regime from 1975 to 1979. At this time, arts and culture almost completely disappeared, as did nearly 20 per cent of the population (between 1.7 million to 3 million people), exterminated by Pol Pot’s dictatorship. The dictatorship fell from power in 1979. Instability and conflict remained for some 20 years.

In 1998, after Pol Pot’s last uprising in 1997, Arn Chorn-Pond founded the Cambodian Master Performer Program, which became Cambodian Living Arts, in order to restore art to its former glory. Born in Cambodia into a family of genocide survivors, he studied in the United States and worked as a social worker there for a few years before returning to Cambodia.

Today, Cambodian Living Arts brings together several hundred artists and employees working at different levels including arts education and heritage protection as well as the development of tomorrow’s leaders, markets and strong networks.

This non-profit organization uses art and culture to fulfil its mission of healing trauma, safeguarding traditions, restoring meaning to the community and training young people to contribute to the development of the country. It now has an expanded ecosystem of partners in other parts of the world.

As Phloeun Prim, the non-profit’s current executive director, explains, the destruction of cultural symbols and artifacts, such as religious and cultural sites, monuments and works of art, is an integral part of the consequences of conflict. The oppressor, be it another country or a dictator, will seek to uproot the oppressed group from its identity, culture and societal vision.

A brutal stop with the pandemic

Although it hasn’t destroyed infrastructure, the global pandemic has hit the cultural sector hard with the closure of theatres and cinemas, bans on mass gatherings and the cancelling of festivals. The performing arts, visual arts and access to heritage often appear to have been last to be considered in reopenings while workers dependent on the gig economy have lost many opportunities.

Read more:

Support for artists is key to returning to vibrant cultural life post-coronavirus

In compensation, the federal and provincial governments have offered some assistance to the sector to survive and to develop.

However, as we can see with the debate around opening performance venues, economic measures are not enough for everyone and do not guarantee that the public will be there. The abrupt and prolonged halt in cultural activities, as well as the prospect of a second wave of COVID-19 contamination, suggest that there will be repercussions for a long time to come. A strategy of cultural regeneration supported by our governments and strong institutions, such as the Cambodian Living Arts in Cambodia, should be considered.

This regeneration work was essential for Cambodia’s recovery. Added to this was the need to transmit culture in order to rebuild bridges between generations, between individuals and between institutions. To share one’s art orally does not only mean passing on know-how. It also means passing on people skills.

(Matthew Wakem), Author provided

By teaching his art, the master transmits his identity to the other. And the student has the duty to appropriate this knowledge in order to take it further and create his own interpretation of the symbols. This is what creates more resilient societies.

Today, Cambodian Living Arts continues to invest in current and future cultural leaders. They are the ones who will have to rebuild in the new post-crisis environment, where interactions, communities and identities will no longer be the same.

Reaching out to the public

At home in Québec, for example, we see local initiatives. TD Bank and Vidéotron have partnered to present musical performances on outdoor stages, in a “drive-in movie” format, where spectators can enjoy the event in their vehicles.

Others choose to travel to people. This is the case of the Théâtre de la Ville, in Longueuil near Montréal, which offers a travelling program of three shows. In this way, art met the public, a bit like street theatre, at the beginning of the confinement. Similarly, Le Festif, in Charlevoix, offers immersive listening sessions outdoors.

Teaching and propagating culture is about coming together and finding each other. Moreover, as noted by the UNESCO International Bureau of Education, every human being is capable, through art, of re-establishing their link with society.

Finding a new normal

Our approach to art, culture and artist-citizen interactions will change in the new post-COVID reality. We will have to relearn, trust each other and then let ourselves forge new ways while respecting the rules.

A study by Habo studio shows that the return to “normalcy” in the consumption of the arts is not coming soon. It will take at least until 2021 (and perhaps 2022, according to some decision-makers in the field) before attendance levels return to pre-COVID levels, at least for the Montréal region.

As Québec’s rules for indoor and outdoor gatherings now vary regionally, the cultural sector continues to explore virtual or outdoor alternatives, and stay attuned to health regulations. Like us, it will be seeking to define its new normal.

Phloeun Prim, Executive Director of Cambodian Living Arts, co-authored this story.

Art

Art and Ephemera Once Owned by Pioneering Artist Mary Beth Edelson Discarded on the Street in SoHo – artnet News

This afternoon in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, people walking along Mercer Street were surprised to find a trove of materials that once belonged to the late feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson, all free for the taking.

Outside of Edelson’s old studio at 110 Mercer Street, drawings, prints, and cut-out figures were sitting in cardboard boxes alongside posters from her exhibitions, monographs, and other ephemera. One box included cards that the artist’s children had given her for birthdays and mother’s days. Passersby competed with trash collectors who were loading the items into bags and throwing them into a U-Haul.

“It’s her last show,” joked her son, Nick Edelson, who had arranged for the junk guys to come and pick up what was on the street. He has been living in her former studio since the artist died in 2021 at the age of 88.

Naturally, neighbors speculated that he was clearing out his mother’s belongings in order to sell her old loft. “As you can see, we’re just clearing the basement” is all he would say.

Photo by Annie Armstrong.

Some in the crowd criticized the disposal of the material. Alessandra Pohlmann, an artist who works next door at the Judd Foundation, pulled out a drawing from the scraps that she plans to frame. “It’s deeply disrespectful,” she said. “This should not be happening.” A colleague from the foundation who was rifling through a nearby pile said, “We have to save them. If I had more space, I’d take more.”

Edelson’s estate, which is controlled by her son and represented by New York’s David Lewis Gallery, holds a significant portion of her artwork. “I’m shocked and surprised by the sudden discovery,” Lewis said over the phone. “The gallery has, of course, taken great care to preserve and champion Mary Beth’s legacy for nearly a decade now. We immediately sent a team up there to try to locate the work, but it was gone.”

Sources close to the family said that other artwork remains in storage. Museums such as the Guggenheim, Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney currently hold her work in their private collections. New York University’s Fales Library has her papers.

Edelson rose to prominence in the 1970s as one of the early voices in the feminist art movement. She is most known for her collaged works, which reimagine famed tableaux to narrate women’s history. For instance, her piece Some Living American Women Artists (1972) appropriates Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1494–98) to include the faces of Faith Ringgold, Agnes Martin, Yoko Ono, and Alice Neel, and others as the apostles; Georgia O’Keeffe’s face covers that of Jesus.

A lucky passerby collecting a couple of figurative cut-outs by Mary Beth Edelson. Photo by Annie Armstrong.

In all, it took about 45 minutes for the pioneering artist’s material to be removed by the trash collectors and those lucky enough to hear about what was happening.

Dealer Jordan Barse, who runs Theta Gallery, biked by and took a poster from Edelson’s 1977 show at A.I.R. gallery, “Memorials to the 9,000,000 Women Burned as Witches in the Christian Era.” Artist Keely Angel picked up handwritten notes, and said, “They smell like mouse poop. I’m glad someone got these before they did,” gesturing to the men pushing papers into trash bags.

A neighbor told one person who picked up some cut-out pieces, “Those could be worth a fortune. Don’t put it on eBay! Look into her work, and you’ll be into it.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Art

Biggest Indigenous art collection – CTV News Barrie

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Biggest Indigenous art collection CTV News Barrie

Source link

Art

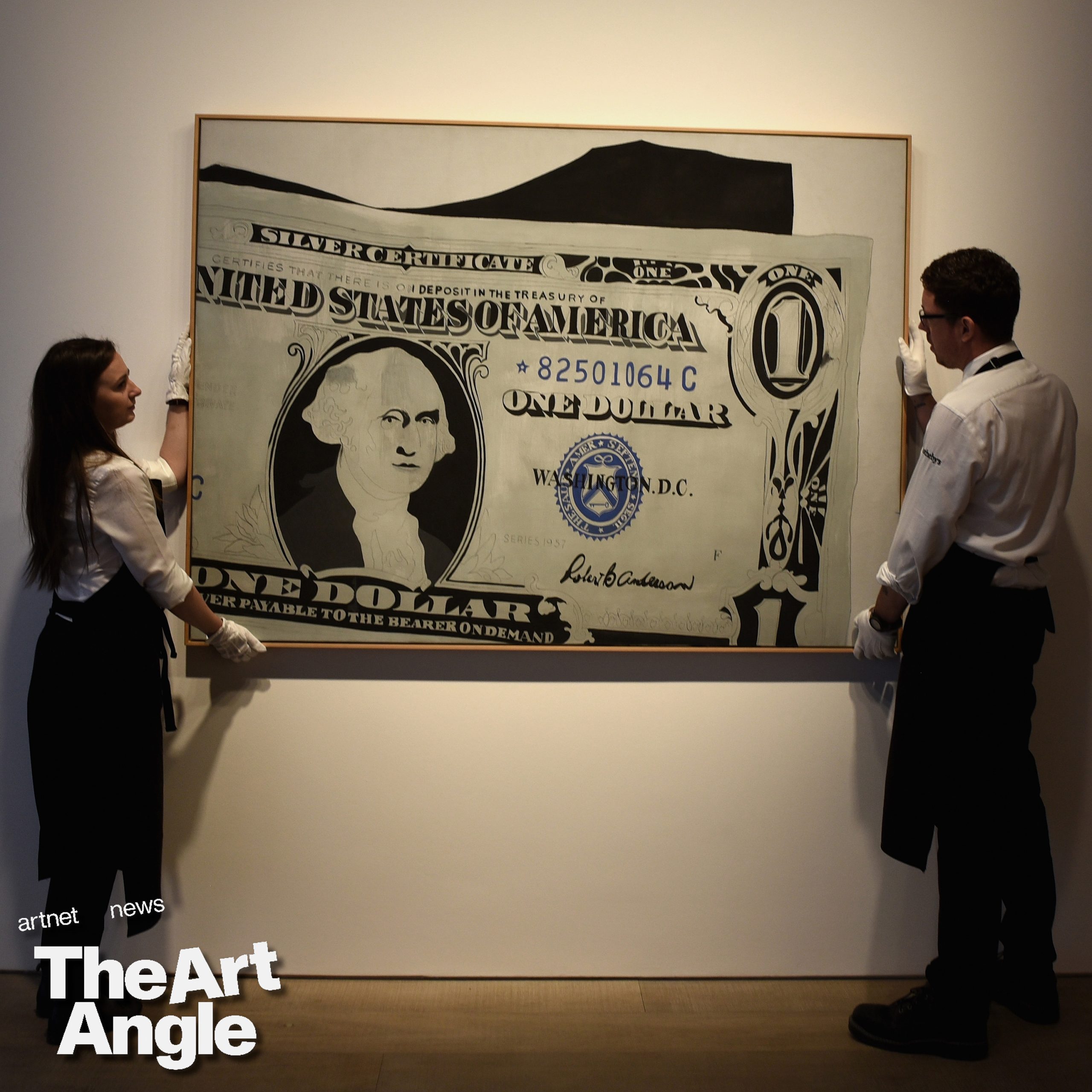

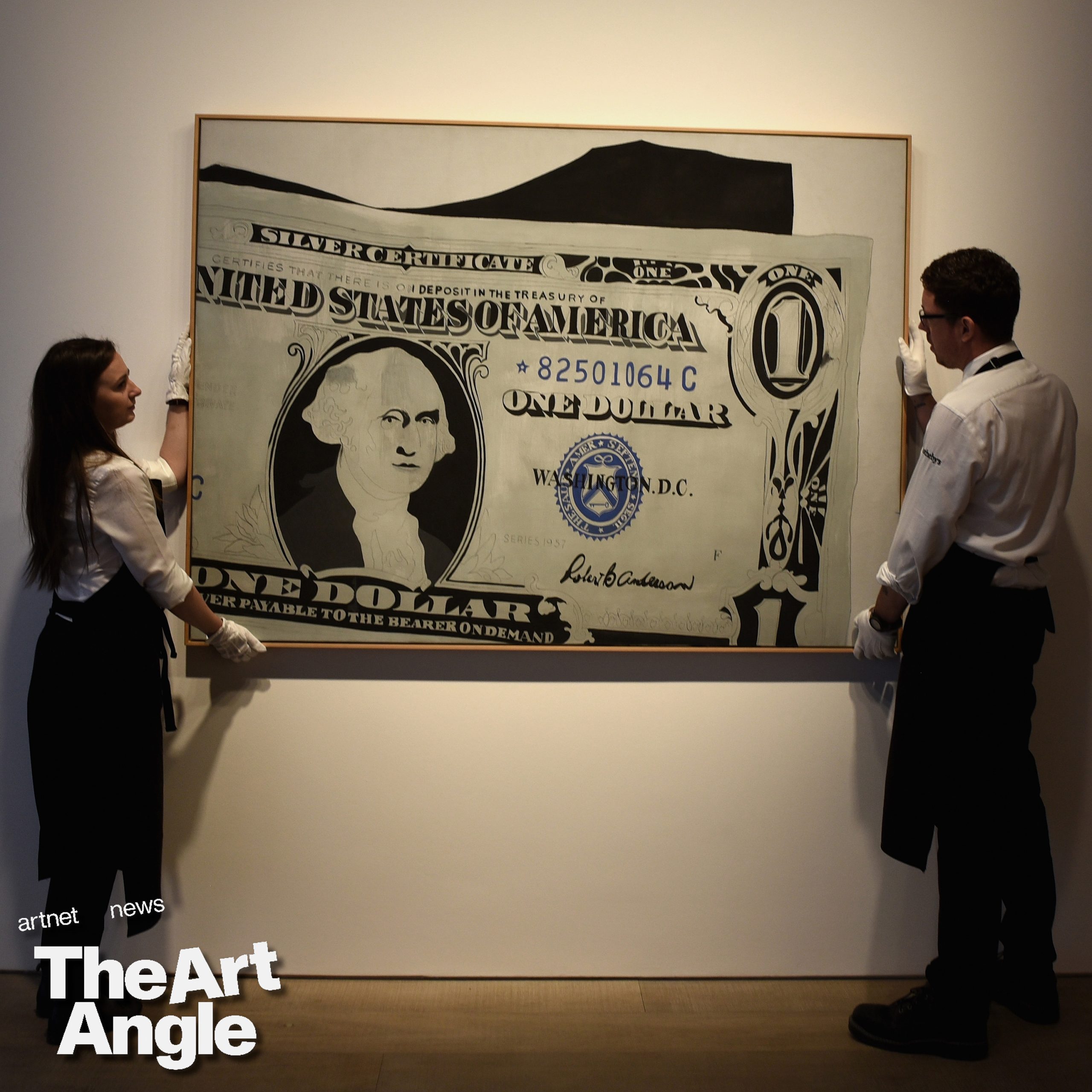

Why Are Art Resale Prices Plummeting? – artnet News

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

-

Media12 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Media14 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Investment13 hours ago

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

-

News23 hours ago

Ontario Legislature keffiyeh ban remains, though Ford and opposition leaders ask for reversal – CBC.ca

-

Sports17 hours ago

Sports17 hours ago2024 Stanley Cup Playoffs 1st-round schedule – NHL.com

-

Business23 hours ago

RCMP national security team investigating Yellowhead County pipeline rupture: Alberta minister – Global News

-

Investment22 hours ago

Investment22 hours agoWant to Outperform 88% of Professional Fund Managers? Buy This 1 Investment and Hold It Forever. – The Motley Fool

-

Health22 hours ago

Health22 hours agoToronto reports 2 more measles cases. Use our tool to check the spread in Canada – Toronto Star