Economy

Coronavirus likely to have severe but short-lived economic impact: Kemp – National Post

LONDON — Epidemics normally have a severe but relatively short-lived impact on economic activity, with the impact on manufacturing and consumption measured in weeks or at worst a few months.

Even pandemics such as the Black Death (1348/49), Spanish influenza (1918/19), Asian influenza (1957/58) and Hong Kong influenza (1968/69) that caused large numbers of deaths had a brief impact on the economy.

China’s coronavirus outbreak should conform to this pattern of a severe downturn followed by swift recovery, provided it does not initiate a broader cyclical slowdown in the already-fragile global economy.

Oil traders are anticipating a deep but short-lived drop in consumption, with the impact concentrated in the first three months of the year and gradually fading in the second and third quarters.

BLACK DEATH

Before modern medicine, the Black Death is estimated have killed between a third and a half of the population of England, and as many as 60 million people worldwide, making it the most lethal single epidemic in history.

The Black Death has become the archetype lethal pandemic, spreading from country to country, and community to community, rapidly killing millions, including many otherwise healthy young adults.

Plague returned periodically to England for the next 150 years, with severe outbreaks in 1361 (“pestis secunda”) and 1368 (“pestis tertia”), and smaller national or local outbreaks in most decades until the early 1500s.

England’s population plunged from around 4.5-6.0 million in 1348 to as little as 2.0-2.5 million a century later and did not fully recover for three or four centuries, according to estimates by historians and demographers.

Following the plagues, England’s economy entered a long agricultural and commercial depression towards the end of the 1300s that lasted through the 1400s, which some scholars blame on depopulation.

In the immediate aftermath of the Black Death, however, the economy seems to have bounced back remarkably quickly given the catastrophic death toll, according to the historian John Hatcher.

“The immense loss of life in the plagues inevitably caused disruption and setbacks in production, but in the greater part these appear to have been short-lived” (“Plague, population and the English economy,” Hatcher, 1977).

“One of the most striking features of the thirty and more years following 1348 was the resilience that the agrarian economy displayed in the face of recurrent plague,” Hatcher observed.

For the most part, agricultural rents and revenues as well as consumption of major commodities rapidly returned to pre-plague levels, and only began to decline from the 1380s or 1390s.

SPANISH INFLUENZA

In more recent times, the outbreak of influenza in 1918/19 is estimated to have killed 675,000 people in the United States and 50 million worldwide, making it the second most deadly epidemic after the Black Death.

The influenza epidemic came in three distinct waves, in the summer and autumn of 1918 and again in early 1919 (“Report on the pandemic influenza 1918-19,” UK Ministry of Health, 1920).

But economic impact in the United States, Britain and many other countries, was very short term and dwarfed by the transition from wartime production to a civilian economy as World War One ended.

In the United States, business conditions were chronicled in the monthly bulletins of the Federal Reserve System, which included a survey regional economic conditions in each of the 12 Federal Reserve districts.

The bulletin made no references at all to influenza for the first 10 months of 1918, then references surge to 17 in November and 23 in December, before falling to just 2 in January and largely disappearing thereafter.

Most of the influenza references in the November and December bulletins are to evidence from business surveys conducted by each of the 12 Federal Reserve Banks in October and November (https://tmsnrt.rs/2SIo6Sm).

In November, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston warned: “The epidemic of influenza which has prevailed during the past month has seriously interfered with business. Production of all kinds has been restricted.”

“Retailers in large centers have had a material falling off in business, while those serving small local trade have to a considerable extent reaped benefits. Conditions are, however, rapidly returning to normal.”

In the Philadelphia District, “retail trade shows a large increase during the month up to the beginning of the influenza epidemic. Since that time, however, the number of customers daily visiting the stores has decreased about one-third and the volume of sales from 30 to 50 percent.”

“Working forces of all business establishments, too, have been affected very much at times, as many as one-third of the employees having been unfit for duty.”

Coal production was hit especially hard, with some collieries being forced to close because so many miners were sick (https://tmsnrt.rs/2HHGrsu).

In the St Louis District, “the influenza epidemic, and the measures taken to combat it, have had a disturbing effect on certain branches of business … Theaters, schools, churches, and other meeting places have been closed entirely, and some of the large stores have been compelled to open later and close earlier than usual.”

“This has especially handicapped retail trade, though other lines have also been affected. Some activities have suffered considerably on account of the depletion of their working forces through contraction of the disease.”

Just a month later, however, most Federal Reserve Banks were already reporting business conditions were returning to normal in the December bulletin.

In the St Louis District, “the influenza epidemic is on the decline … and the bans placed on business to combat it, in most instances, have been lifted. Department stores, theaters, etc, are now operating as usual, and schools, churches, lodges, etc, are again open. This has materially helped the retail trade.”

In the Richmond District, “the subsidence of the prevalent influenza permitted the reopening of churches, schools, and other places of gathering.”

“Manufacturing continues active with the prevailing restriction of supplies and labor. The effects of the influenza are passing and mills are resuming more normal operations.”

LATER PANDEMICS

The precise economic impact of the epidemic of 1918/19 is hard to isolate because it coincided with the end of wartime production and the transition to a post-war civilian economy.

But there are no signs of lasting disruption: a pandemic that killed 50 million people worldwide has left almost no trace in the economic record.

Further influenza pandemics were reported in 1957/58 and 1968/69 but in both cases the number of extra deaths was low and there was no discernible economic impact.

More recently, the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) in 2003, caused only a brief interruption in economic activity and oil consumption.

In most cases, the main impact on the economy has come from public health measures, such as quarantines, isolation and business closures, intended to control the spread of disease, rather than from the disease itself.

As a result, policymakers face a difficult trade-off between stringent public health measures to contain the epidemic and the need to resume normal business and social activities as soon as possible.

Over time, policymakers, business owners and employees face increasing pressure to resume near-normal operations, while taking practical steps to reduce if not eliminate transmission risk.

China’s government is trying to encourage a gradual normalization of business activity and transport in the rest of the country outside Hubei, the province at the center of the outbreak.

If the past is any guide, economic activity and oil consumption should return to normal over the next 3-6 months, which is why Brent prices and calendar spreads have been progressively strengthening over the last 10 days.

The main remaining risk is that the short-term economic shock from coronavirus could push the global economy, which was only just recovering from the trade war of 2018/19, into a full-blown cyclical downturn.

Related columns:

– Oil prices bounce on hope for short coronavirus downturn (Reuters, Feb. 17)

– Falling air freight points to renewed global economic slowdown (Reuters, Feb. 13)

– Coronavirus and the impact on oil consumption (Reuters, Feb. 5) (Editing by David Evans)

Economy

Limiting Global Warming to 1.5C Would Avoid Two-Thirds of Economic Toll – Bloomberg

Climate inaction will depress the world’s economy more than previously estimated, according to a new study that takes into account the impacts of weather extremes and variability such as temperature spikes and intense rainfall.

A scenario in which global temperatures rise 3C on average will reduce the world’s gross domestic product by about 10%, doctoral researcher Paul Waidelich of ETH Zurich and colleagues write, with less developed countries paying the worst toll. By comparison, limiting global warming by 2050 to 1.5C — as sought by the Paris Agreement — will reduce that impact by about two-thirds.

Economy

PM: Millennials and Gen Z drive Canadian economy – CTV News Montreal

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

- PM: Millennials and Gen Z drive Canadian economy CTV News Montreal

- Canada’s budget 2024 and what it means for the economy Financial Post

- Federal budget is about ensuring fair economy for ‘everyone’: Trudeau Global News

Economy

Climate Change Will Cost Global Economy $38 Trillion Every Year Within 25 Years, Scientists Warn – Forbes

Topline

Climate change is on track to cost the global economy $38 trillion a year in damages within the next 25 years, researchers warned on Wednesday, a baseline that underscores the mounting economic costs of climate change and continued inaction as nations bicker over who will pick up the tab.

Key Facts

Damages from climate change will set the global economy back an estimated $38 trillion a year by 2049, with a likely range of between $19 trillion and $59 trillion, warned a trio of researchers from Potsdam and Berlin in Germany in a peer reviewed study published in the journal Nature.

To obtain the figure, researchers analyzed data on how climate change impacted the economy in more than 1,600 regions around the world over the past 40 years, using this to build a model to project future damages compared to a baseline world economy where there are no damages from human-driven climate change.

The model primarily considers the climate damages stemming from changes in temperature and rainfall, the researchers said, with first author Maximilian Kotz, a researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, noting these can impact numerous areas relevant to economic growth like “agricultural yields, labor productivity or infrastructure.”

Importantly, as the model only factored in data from previous emissions, these costs can be considered something of a floor and the researchers noted the world economy is already “committed to an income reduction of 19% within the next 26 years,” regardless of what society now does to address the climate crisis.

Global costs are likely to rise even further once other costly extremes like weather disasters, storms and wildfires that are exacerbated by climate change are considered, Kotz said.

The researchers said their findings underscore the need for swift and drastic action to mitigate climate change and avoid even higher costs in the future, stressing that a failure to adapt could lead to average global economic losses as high as 60% by 2100.

!function(n) if(!window.cnxps) window.cnxps=,window.cnxps.cmd=[]; var t=n.createElement(‘iframe’); t.display=’none’,t.onload=function() var n=t.contentWindow.document,c=n.createElement(‘script’); c.src=’//cd.connatix.com/connatix.playspace.js’,c.setAttribute(‘defer’,’1′),c.setAttribute(‘type’,’text/javascript’),n.body.appendChild(c) ,n.head.appendChild(t) (document);

(function()

function createUniqueId()

return ‘xxxxxxxx-xxxx-4xxx-yxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx’.replace(/[xy]/g, function(c) 0,

v = c == ‘x’ ? r : (r & 0x3 );

const randId = createUniqueId();

document.getElementsByClassName(‘fbs-cnx’)[0].setAttribute(‘id’, randId);

document.getElementById(randId).removeAttribute(‘class’);

(new Image()).src = ‘https://capi.connatix.com/tr/si?token=546f0bce-b219-41ac-b691-07d0ec3e3fe1’;

cnxps.cmd.push(function ()

cnxps(

playerId: ‘546f0bce-b219-41ac-b691-07d0ec3e3fe1’,

storyId: ”

).render(randId);

);

)();

How Do The Costs Of Inaction Compare To Taking Action?

Cost is a major sticking point when it comes to concrete action on climate change and money has become a key lever in making climate a “culture war” issue. The costs and logistics involved in transitioning towards a greener, more sustainable economy and moving to net zero are immense and there are significant vested interests such as the fossil fuel industry, which is keen to retain as much of the profitable status quo for as long as possible. The researchers acknowledged the sizable costs of adapting to climate change but said inaction comes with a cost as well. The damages estimated already dwarf the costs associated with the money needed to keep climate change in line with the limits set out in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, the researchers said, referencing the globally agreed upon goalpost set to minimize damage and slash emissions. The $38 trillion estimate for damages is already six times the $6 trillion thought needed to meet that threshold, the researchers said.

Crucial Quote

“We find damages almost everywhere, but countries in the tropics will suffer the most because they are already warmer,” said study author Anders Levermann. The researcher, also of the Potsdam Institute, explained there is a “considerable inequity of climate impacts” around the world and that “further temperature increases will therefore be most harmful” in tropical countries. “The countries least responsible for climate change” are expected to suffer greater losses, Levermann added, and they are “also the ones with the least resources to adapt to its impacts.”

What To Watch For

The fundamental inequality over who is impacted most by climate change and who has benefited most from the polluting practices responsible for the climate crisis—who also have more resources to mitigate future damages—has become one of the most difficult political sticking points when it comes to negotiating global action to reduce emissions. Less affluent countries bearing the brunt of climate change argue wealthy nations like the U.S. and Western Europe have already reaped the benefits from fossil fuels and should pay more to cover the losses and damages poorer countries face, as well as to help them with the costs of adapting to greener sources of energy. Other countries, notably big polluters India and China, stymie negotiations by arguing they should have longer to wean themselves off of fossil fuels as their emissions actually pale in comparison to those of more developed countries when considered in historical context and on a per capita basis. Climate financing is expected to be key to upcoming negotiations at the United Nations’s next climate summit in November. The COP29 summit will be held in Baku, the capital city of oil-rich Azerbaijan.

Further Reading

-

News21 hours ago

Loblaws Canada groceries: Shoppers slam store for green onions with roots chopped off — 'I wouldn't buy those' – Yahoo News Canada

-

News24 hours ago

Toronto airport gold heist: Police announce nine arrests – CP24

-

Investment20 hours ago

Saudi Arabia Highlights Investment Initiatives in Tourism at International Hospitality Investment Forum

-

Business20 hours ago

Rupture on TC Energy's NGTL gas pipeline sparks wildfire in Alberta – The Globe and Mail

-

Art20 hours ago

Squatters at Gordon Ramsay's Pub Have 'Left the Building' After Turning It Into an Art Café – PEOPLE

-

Tech13 hours ago

Tech13 hours agoCytiva Showcases Single-Use Mixing System at INTERPHEX 2024 – BioPharm International

-

Sports23 hours ago

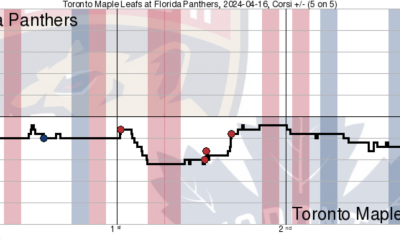

Sports23 hours agoGame in 10: Maple Leafs squander multi-goal lead to Florida, draw the Boston Bruins in the first round – Maple Leafs Hot Stove

-

Politics20 hours ago

Politics20 hours agoThe Earthquake Shaking BC Politics