Art

David Lee Roth Is Letting His Art (Mostly) Do the Talking – The New York Times

Typically, David Lee Roth spends his days, or at least his nights, “in tactical spandex, moving at 134 beats per minute,” he said. But now the 65-year-old Van Halen singer is just like the rest of us: stuck at home and obsessing about pandemics.

However, the past few months in quarantine have led Roth to an old pursuit, with new focus. Since April, he has filled his days creating Covid-themed drawings — he calls them comics — and then sharing the finished works, one each week, on his social media channels. The art, like Roth’s music and disposition, is vibrant, whimsical and somewhat unconventional. In moments, it is confrontational. Several drawings feature his own face. Many are filled with images of frogs.

What sparked this surge of artistic expression?

“Well, I lost my job!” Roth cracked over the phone from his home in Los Angeles on an afternoon in late June. As recently as March, Roth was on tour as a solo act, supporting Kiss in arenas across the United States. Earlier in that run, Roth, who has also worked as an E.M.T. in New York, had battled an unspecified illness. “I’m not so unconvinced I didn’t have the corona,” he said. “Man, they gave me enough prednisone to put boots on the moon! We left a trail of groupies, rubble and incandescent reviews. But I don’t want to go back through it.”

Even by rock frontman standards, Roth’s ability to command full attention from his audience is renowned, whether he’s launching himself off drum risers for midair splits or schooling fans on how Van Halen is “the rock ’n’ roll band who sold Ricky Ricardo rumba to the heavy metal nation.” But now his art is doing the talking. “Social commentary is what I do,” he said. “It’s what I’ve always done.”

In his recent artwork, that social commentary has elicited a strong response. In one piece, he declares a name change. “Diamond Dave following Lady Antebellum’s (now ‘Lady A’) example, will be dropping the ‘Lee,’” he wrote below a drawing of, naturally, a frog. “From now on he wants us all to call him ‘David L. Roth’ or simply ‘El Roth.’” To many, it diminished the steps white artists are taking to correct racism.

“Humor — not jokes — humor, the best stuff, isn’t funny at all,” Roth said, defending his work. “My version is the truth dipped in sugar. And maybe it’s a little sugar and spice. But the good stuff compels discussions.”

Art, he continued, “has been a constant in my life. My hand has always been in wardrobe, background sets, stage sets, album covers, video direction. This is part of it. And there’s craft involved, so there’s a little bit more heft to some of the statements.”

Roth laughed. “This is the adult table; as a fellow artist, I sense you understand that.”

Another laugh.

“Next question!” These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

Why frogs?

I saw a story about Mark Twain — it was not his biography, it was a fictional piece with actors. And at the end of it ol’ Sam passes on, but he doesn’t go to heaven. He’s in the backyard where he grew up in Hannibal, Mo. And a little girl walks up and he goes, “Who are you?” She says, “I’m Becky Thatcher, and I’ve got some friends who are waiting to meet you.” And all the characters that he created come on up to greet him. So, I started my guest list. And probably the only one of that retinue that I could even spell, much less draw, was the frog from Calaveras County [from the short story “The Celebrated Jumping Frog of Calaveras County”].

Many of your drawings include a reference to the “Soggy Bottom.” I took this, at least in this context, to be a play on the phrase “draining the swamp.”

If I explain it, it’s a bumper sticker. If I let you explain it, it’s art. But you’re very close to exactly accurate.

Can you describe your artistic process?

My approach is the best of both worlds: vintage and hyper-atomic digital. Sort of like watching “Dragnet” on your iPad. You know, I moved to Japan for two-plus years to study Sumi-e and calligraphy, and four nights a week I trained and then I did homework. Jesus, I’ve spent thousands of hours learning to operate a horsehair brush with a block of ink that I grind myself. Hasn’t changed its recipe in 700 years.

So everything in the comics is hand-drawn — all the typeface, all the colors, the line work, the lighting. And once I’m done, I work with Colin Smith, the Led Zeppelin of Adobe Photoshop. Together we scan everything, and then I’m able to move into areas that otherwise weren’t graphically available without decades of effort.

How does using digital manipulation transform the original work?

Many of these colors can’t be found outside the cyberverse. It’s a world unto itself. Serves a well purpose, because almost all of our fine arts and graphic consumption these days is interactive with a screen, whether it’s on your PC or your wristwatch. We’re actually back to Maxwell Smart and his shoe phone. “Somebody is on my Nike!”

What appeals to you about using brush and ink as a means of artistic expression?

Hold on. This isn’t expressing myself. This is performance therapy. I’m venting. I’m angry. And I am not asking for forgiveness. And this is how I do it.

People don’t usually think of David Lee Roth as angry.

That’s because I have transcended it. It is that secret magic when you take something that is essentially sad and find humor, eloquence and sometimes illumination in it.

What is your view of this country’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic?

I sure wish our country had taken a Marine Corps approach to Covid. Instead of [creating] a divide, good or bad, right or reasonable, wrong or otherwise.

One of your pieces features the phrase “No politics during happy hour,” which feels to me like it could be an encapsulation of the Van Halen ethos.

Well, visually and graphically, the frogs underneath that caption are fighting — identical to what happened in my brief and colorful tenure with the Van Halens. [Laughs] But when you see Technicolor frogs doing it, it’s a bit more digestible. But what I’m reflecting on in that comic is the unstated. That which we don’t talk about. What does happen when we drink at happy hour and talk politics? What does it mean when we say, “Alcohol sales skyrocket again”? It’s all a bit of a diversion.

Can you say more about the piece that seems to be a response to Lady Antebellum’s name change?

It had connotations of personal politic. I sought to have a little fun at the expense of others, whose vision I will respect. And in lieu of the inevitable false-footed copycats I pretended to be one. But the supposed name change really drew some ire in terms of some folks posting from an arch right-wing stance: “Another left-winger takes a fall.” Hey, I’m a combat hippie — peace, love and enough guys and gears to defend the [expletive] out of it. You need one to support the other.

Would it be correct to identify David Lee Roth as left-leaning?

I love civil rights. Equal rights. Women’s rights. Kids’ rights. The rights of the rights. OK? The entire list. But conversely, I’m prepared to shave my head, join the Marines and go defend those rights. That in itself isn’t really a left-wing statement. Or it didn’t used to be when I was growing up. But I grew up in a really great time and a really great space during integrational busing in the ’60s. I went to schools that were 90 percent Black and Spanish, and I was in the color guard with a crew cut. Every morning at seven we’d march to put up the flag. And then at night we’d go to Kenny Brower’s brother’s house, smoke pot and listen to that new Doors record. Combat hippie!

You were on tour when the lockdown began. As a lifelong performer, was it difficult being forced to leave the road so hastily?

Every Jiu-Jitsu magazine has a 28-year-old who’s going to tell you about the two years that got taken away by his elbow. Every kickboxing magazine has a 32-year-old instructor who goes, “Well, I lost those three years to my left knee.” So I’ve just been isolating away. Because I myself am high risk.

Why do you consider yourself high risk?

The road will deteriorate you from the beginning or it will keep you alive forever. When we go out, we wear ourselves to a nubbin. I just had a lower back surgery. It was a spinal fusion where they take a chip from somebody else. I’m actually taller now. Do I seem taller? I mean, over the phone?

You last toured with Van Halen in 2015. Do you think it’ll ever happen again?

I don’t know that Eddie [Van Halen] is ever really going to rally for the rigors of the road again. [The guitarist first announced he had cancer in 2001, and it has recurred since.] I don’t even want to say I’ve waited — I’ve supported for five years. Because what I do is physical as well as musical and spiritual — you can’t take five years off from the ring. But I did. And I do not regret a second of it. He’s a band mate. We had a colleague down. And he’s down now for enough time that I don’t know that he’s going to be coming back out on the road. You want to hear the classics? You’re talking to him.

For how long will we continue to see new artwork from David Lee Roth?

Like the tattoo artist said, ’til I don’t have any friends left! Until my Instagram’s empty! I can do this endlessly. I hadn’t considered this as something other than after dinner at the campfire. But lo and behold, people have taken a real fascination.

Given that fascination, will these drawings eventually be offered for sale?

In terms of what I really do for a living, as soon as the B-list — that’s Beyoncé, Bono and Bruce [Springsteen] — say it’s OK, I’ll be back singing and dancing and selling you T-shirts. But in the interim, I am drawing and painting every night. And the fact that there’s an audience for it is quite a tickle. So of course I’ll make it available. You bet. I just didn’t see it coming. [Laughs] But like my sister says, I seem to miss the big stuff.

Art

Get inspired at the Manotick Inspirations Art Show – CTV News Ottawa

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Get inspired at the Manotick Inspirations Art Show CTV News Ottawa

Source link

Art

The Wall Street lawyer who quit to make Lego art: ‘It is a job, not a hobby’ – The Guardian

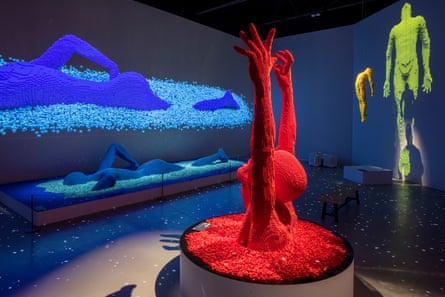

He’s made a living out of building sculptures from Lego and his work has been shown in 100 cities and 24 countries, attracting millions of visitors. But you won’t find any Lego in Nathan Sawaya’s home. Call it work-life balance: “I love what I do, but it is a job … not a hobby,” the 50-year-old American artist says.

It is a job, but it’s also something like a dream. Sawaya was a Wall Street lawyer who was unhappy with his career, playing with his favourite childhood toys after hours to unwind. Creating elaborate sculptures from scratch wasn’t unfamiliar to him – as a child, when his parents wouldn’t buy him a dog, he fashioned a lifesize pet from Lego bricks. “It was very rudimentary, but it was what I could do as a kid,” he recalls.

Sawaya began posting photos of his sculptures online. When his website crashed from all the clicks, he took it as a sign to quit law and pursue Lego. The first iteration of Sawaya’s travelling exhibition, the Art of the Brick, was held at a small art museum in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 2007, featuring about two dozen sculptures. “I treated it like a wedding and invited all my friends and family from all over,” he says. “I expected that to be my last solo show, but fortunately it has kept going ever since.”

Initially, Sawaya was met with resistance from Lego – the company’s first ever contact was a cease and desist. But he eventually went to work for Lego as a master model builder (the people who build the models for Legoland and other official operations). The audition process sounds simple enough, but it requires skill. “They say: here’s a pile of bricks, build a sphere out of it. You build the sphere and they roll it across the table or the floor to see how you did.”

After a short stint with Lego, Sawaya branched out on his own. He’s now a Lego certified professional, a title reserved for those who have made their own businesses from the bricks. “It’s a very good business relationship,” Sawaya says of his dealings with Lego these days. He has to buy the bricks, like anyone else. “I understand that they’re a toy company, and they understand that I’m an artist.”

Is there any tension in making art from a branded product? “Of course,” he says. “I’m subject to the decisions of a third party.” For example, he’s limited to the colours that Lego produces – he gets around this by having an extensive inventory of about 10m bricks between his two studios in Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

Sawaya doesn’t see his exhibition as promotional for Lego – “I don’t call the show the art of Lego,” he points out – but he acknowledges that the accessibility that makes him love the medium so much also equates to something of a monopoly. “It is still a brand, and that is a part of it,” he says. “When you get up very close to every sculpture of mine, you can see the word Lego on every individual piece.”

The Art of the Brick, which has just opened in Melbourne, has been a worldwide hit – there are three or four exhibitions running simultaneously at any given time. “They’re all different, but there are favourites that I’ve replicated because there’s some expectation that certain pieces are going to be there,” he says.

Sawaya’s most well-known piece is 2007’s Yellow, a sculpture of a man opening his own chest to reveal Lego pieces spilling out – Lady Gaga superimposed her head on to it in the video for her 2014 single G.U.Y. At the Melbourne show it looms large, surrounded by seven smaller-scale versions in different colours.

But there are plenty more. Sawaya doesn’t keep count of how many sculptures he’s created over the past two decades, but estimates that it might be close to a thousand. He’s made a six-metre-long Batmobile and a lifesize replica of Central Perk, the cafe from Friends, with fellow Lego artist Brandon Griffith, which required 1m bricks.

So what goes into planning a Lego sculpture on this level? “It depends on the piece, of course, but it all starts with the idea,” he says. “There’s some mapping that goes into it – sometimes it’s just drawing it out. Sometimes it’s digital.

“There’s also a lot of research that goes into it: am I doing a piece that people are familiar with? If it’s a replica – let’s say an art history piece – that’s going to require going and looking at the original, gathering photographs and whatnot. If it’s just pouring out of my brain, then it’s more trial and error.”

In Melbourne, Sawaya’s works are animated with kinetics for the first time – 250 glowing skulls move in mesmerising waves against a mirrored wall, with lights and music adding a new dimension. In another room, there’s a lit-up recreation of Formula One driver Lando Norris’s helmet at an 18:1 ratio; in yet another, realistic animals, including a giraffe and a polar bear mother and cub, are projected against their natural habitats in a collaboration with the Australian photographer Dean West.

These creations are undeniably impressive, but peer into some corners of the internet and you’ll find some people asking: is it art? In Sawaya’s mind, at least, it doesn’t matter. “I leave it up to the art critics and students to decide what the art world thinks,” he says. “I’m not striving for it – I’m just doing my own thing.”

-

The Art of the Brick is on now at Melbourne Showgrounds.

Art

Faith Ringgold Perfectly Captured the Pitch of America's Madness – The New York Times

Faith Ringgold, who died Saturday at 93, was an artist of protean inventiveness. Painter, sculptor, weaver, performer, writer and social justice activist, she made work in which the personal and political were tightly bonded. And much of that work gained popularity among audiences that didn’t necessarily frequent galleries and museums. This was particularly true of her series of semi-autobiographical painted narrative quilts depicting scenes of African American urban childhood, subject matter that translated readily into illustrated children’s books, of which, over the years, Ringgold published many.

Altogether, hers added up to a landmark-status career. But the art establishment, as defined by major museums, big-bucks auction houses and a few talent-hogging galleries, never knew quite what to do with it, or with her. So they didn’t do anything. No mega-surveys, no million-dollar corporate commissions, no Venice Biennale-type canonizations.

Recently, though, very late in the day, came a serious uptick in attention. In 2016, the Museum of Modern Art finally brought Ringgold into its collection with the acquisition of several pieces from early in her career. One of them was a monumental 1967 painting titled “American People Series #20: Die.” It shows a crowd of panicked men, women and children, white and Black, screaming and bleeding, and stampeding in all directions as if under lethal attack from some unseen force.

It’s useful to remember where Ringgold stood in her life at the time she painted the picture. Harlem-born, she’d had a classical art education, was teaching art in public school, and was painting what she herself described as Impressionist-style landscapes. She was also reading James Baldwin, listening to the news, and seeing American racial politics shift from civil rights-era passive resistance to a newly assertive Black power. The country was on red alert, just as it is today, and her art responded to the emergency by turning topical.

In the paintings she called the “American People Series,” of which “Die” was one, white people and Black people appear together, but with skewed power balances made clear. In an early picture, “The Civil Rights Triangle” from 1963, five men in business suits, four Black, one white, form a pyramid, with the white man on top, indicating that to the extent the civil rights movement was white-approved, it was also white-controlled.

In “Die,” the culminating picture in the series, a full-on war has erupted, though one that goes beyond being a clear-cut race war. All the figures in the picture look equally stunned and traumatized by the blood bath they find themselves in.

And for Ringgold at this time, art itself went beyond being the seismic recorder of a culture. It also became a vehicle for path-clearing and ethical advocacy. She organized protests against the exclusion of Black artists from leading museums, and designed posters in support of the Attica inmates and the activist Angela Davis. In a painting series called “Black Light,” she eliminated white pigment from her palette and mixed black into all her colors. By the 1970s she had become convinced that Black liberation and women’s liberation were inseparable causes. In 1971 she painted a mural for what was then the Women’s House of Detention on Rikers Island.

She knew that the country she lived in was actively, murderously crazy. For an artist to find a voice for that craziness, to get the pitch of the madness right, was unusual and daring. For that artist to be Black and female was more than unusual, and met with pushback from many sources, most of them within the art world itself.

The kind of painting she favored — figurative, storytelling, polemical — was out of fashion with the establishment, which well into the ’60s touted abstraction as the only “serious” aesthetic mode. (Even within Black art circles a debate over whether modern art, Black or otherwise, should admit political content was very much alive.) And her work continued to run against the grain throughout the Minimalist and Conceptualist years. It’s only recently, with figurative painting hugely in vogue, that her work has gained something like market currency.

And over the decades she continued to develop in new directions. Her formal means grew ever more craft-intensive, incorporating weaving, sewing and carving. Her political content drew less from the news and more from art history and her own life. Her determination to share this content, often determinedly Black-positive in tone, with young audiences through 20 published children’s books is all but unique in contemporary art annals.

The full range of these developments was on display in an overdue retrospective, “Faith Ringgold: American People,” organized by the New Museum in 2022. But back to Ringgold at MoMA in 2019.

For the opening of its newly expanded premises, the museum was rehanging, top to bottom, its permanent collection galleries, and “Die,” a relatively recent arrival, was chosen for inclusion. More than that, it was awarded a starring role. It shared an otherwise sparsely installed gallery with a major MoMA attraction, Picasso’s 1907 “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” a confrontational image of five nude Catalan prostitutes with sliced-up bodies and faces like African masks.

The two paintings were placed cater-corner in the gallery, so you could take them in together at a glance. Both are violent. (The colonialist implications of “Demoiselles” have been much noted, and art historians have read the picture as, among other things, an expression of male sex panic.) Both register as scorchingly political, while leaving their precise politics unclear. Paired at MoMA, they seemed to be visually and conceptually duking it out.

For me, Ringgold — an avowed Picasso fan — won the match. But what really mattered was simply that she was there, smack in the center of Western Modernism’s ground zero institution, and with her most radical image. I admire Ringgold’s later art, much of it materially innovative and expressively buoyant. But it’s the early work, from the pivotal period that produced “Die,” that I keep coming back to.

What she managed to do, in those early paintings, was put aside all the conventional art tools she’d been schooled with, beauty among them (she would later reclaim it), in order to face down the world as it really was, including an art world that had no use for her — a Black woman — and was, in fact, fortressed to keep her and everyone like her out.

Certain artists manage to leap over walls. Picasso was one. And some tunnel under those walls, hit resistance, tunnel some more and, once inside, open a door to let others in. That’s what Faith Ringgold, artist-activist to the end, did.

-

Media16 hours ago

Trump Media plunges amid plan to issue more shares. It's lost $7 billion in value since its peak. – CBS News

-

Business24 hours ago

Tesla May Be Headed For Massive Layoffs As Woes Mount: Reports – InsideEVs

-

Tech20 hours ago

Tech20 hours agoJava News Roundup: JobRunr 7.0, Introducing the Commonhaus Foundation, Payara Platform, Devnexus – InfoQ.com

-

Real eState20 hours ago

Real estate mogul concerned how Americans will deal with squatters: ‘Something really bad is going to happen’ – Fox Business

-

Sports19 hours ago

Sports19 hours agoRafael Nadal confirms he’s ready for Barcelona: ‘I’m going to give my all’ – ATP Tour

-

Art22 hours ago

Art Bites: The Movement to Remove Renoir From Museums

-

Science20 hours ago

Total solar eclipse: Continent watches in wonder – Yahoo News Canada

-

Investment17 hours ago

Investment17 hours agoLatest investment in private health care in P.E.I. raising concerns – CBC.ca