Sports

Do host countries make money from the World Cup?

|

|

The football World Cup is the biggest sporting event in the global calendar … ahead even of the Olympics.

More than five billion people are expected to tune in to watch the sporting spectacular in Qatar, with more than a million turning up to watch the games in person.

From ticket and merchandise sales to corporate sponsorship, prize money and tourism, there are immense amounts of money kicking around an event like this.

But, for a host country, is it financially worth it? The short answer is no.

Most countries hosting a World Cup spend tens of billions on preparations, developing infrastructure, building hotels and so on. Much of that is often not recouped, at least not in terms of hard cash.

The World Cup certainly is a money-spinner. TV rights for the 2018 World Cup in Russia were sold to broadcasters around the world for $4.6bn. But that is kept by FIFA, football’s world governing body.

As are ticket sales, which are owned by a subsidiary company 100 percent owned by FIFA. Marketing rights, which brought in more than $1bn in the 2018 cycle are, too, kept by FIFA.

The body does, however, cover the principal costs of running the tournament – it will be paying Qatar in the region of $1.7bn, though that includes a $440m prize pot for teams.

But Qatar is understood to have spent in excess of $200bn on this World Cup and the infrastructure around it – hotels and leisure facilities, overhauling its entire road network and constructing a rail system.

With more than a million overseas visitors expected during the month-long tournament, a host country will see a tourism spike, increasing sales for hoteliers, restaurateurs and the like. But such a surge requires extra capacity to be built, the expense of which is usually far larger than the revenues generated short term.

And who benefits in the short term?

The World Economic Forum reports: “Hotel prices rise during sell-out events, but wages of service workers do not necessarily go up by the same amount, meaning the returns to capital are likely greater than those to labour.”

People with money make money. People without it, don’t.

Furthermore, World Cup tourists buying merchandise, drinks or anything else from FIFA partner brands are not contributing to a host country’s tax revenues, as enormous tax breaks for FIFA and its sponsor brands are required within a World Cup bidding process.

Germany touted $272m in tax breaks in its bid to host the 2006 World Cup.

Non-World Cup tourists tend to stay well clear of a host country during a World Cup, keen to avoid the crowds, traffic and inflated prices. For Qatar 2022, if you don’t have a match ticket, you are unable to enter the country from November 1 to the end of the World Cup.

In the short term at least, it doesn’t make financial sense to host a football World Cup. But some things are bigger than money.

Hosting a World Cup is an exercise in the projection of soft power. It gives the world a window into that country, showing how new infrastructure makes it a good place in which to invest or to do business.

And in the longer term, the money spent on hosting, if managed correctly, builds capacity for that country’s economy to expand.

New roads and transport projects will provide economic benefits for years after the final whistle is blown at a World Cup.

Huge international sporting events bridge societal divides and bring people together across borders – the 2018 Winter Olympics saw North and South Korea enter the stadium under a common flag. These events also encourage children to take up sport – which has economic benefits to a host nation’s healthcare system further down the line.

For a host country, a World Cup is about pride and honour and publicity, more than it is about making money.

Hosting a World Cup is a nation opening its arms and its homes and saying to the world: “Hayya, you are welcome here.”

Sports

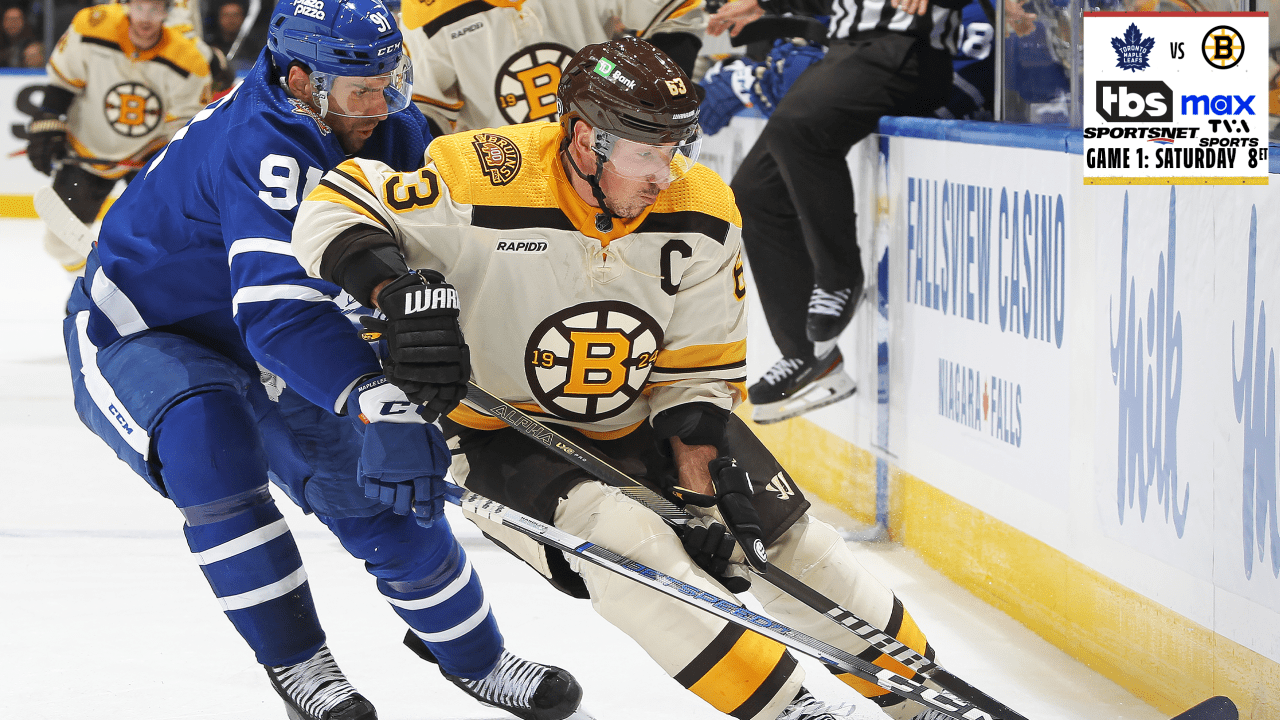

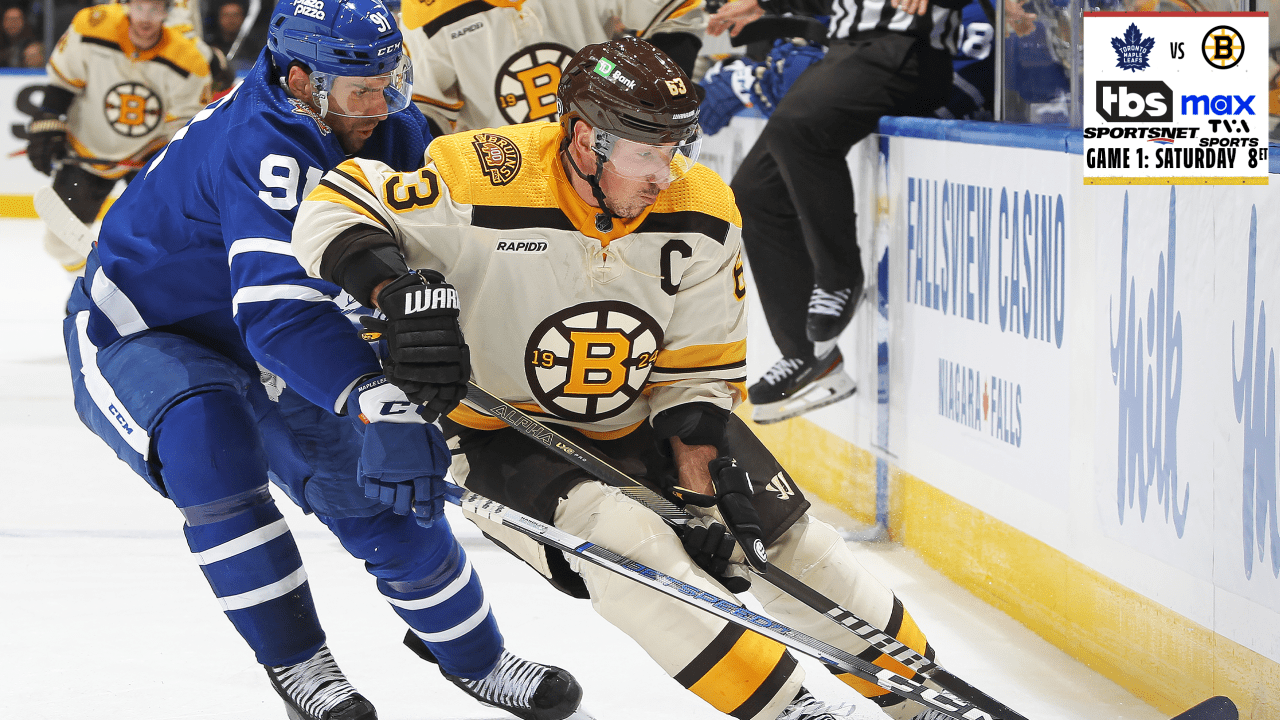

Marchand says Maple Leafs are Bruins’ ‘biggest rival’ ahead of 1st-round series – NHL.com

BOSTON – Forget Boston Bruins-Montreal Canadiens.

For Brad Marchand, right now, it’s all about Bruins-Toronto Maple Leafs.

“You see the excitement they have all throughout Canada when they’re in playoffs,” Marchand said Thursday. “Makes it a lot of fun to play them. And I think, just with the history we’ve had with them recently, they’re probably our biggest rival right now over the last decade.

“They’ve probably surpassed Montreal and any other team with kind of where our rivalry’s gone, just because we’ve both been so competitive with each other, and we’ve had a few playoff series. It definitely brings the emotion, the intensity, up in the games and the excitement for the fans.

“It’s a lot of fun to play them.”

The Bruins and Maple Leafs will renew their rivalry in their first round series, which starts Saturday at TD Garden (8 p.m. ET; TBS, truTV, MAX, SN, CBC, TVAS). They’ll be familiar opponents.

Over the past 11 seasons, the Bruins have faced the Maple Leafs four times in the postseason, starting with the epic 2013 matchup in the first round. That resulted in an all-time instant classic, the Game 7 in which the Bruins were down 4-1 in the third period and came roaring back for an overtime win that helped propel them to the Stanely Cup Final.

That would prove to be the model and, in the intervening years, the Bruins have beaten them in each of the three subsequent series, including going to a Game 7 in the Eastern Conference First Round in 2018 and 2019.

Which could easily be where this series is going.

“Offensively they’re a gifted hockey club,” Bruins general manager Don Sweeney said Thursday. “They present a lot of challenges down around the netfront area. We’re going to have to be really sharp there. We’re a pretty good team defensively when we stick to what our principles are. So I expect it to be a tight series overall.”

But if anyone knows the Maple Leafs — and what to expect — it’s Marchand. In his career, he’s played 146 games in the Stanley Cup Playoffs, 11th most of any active player. Twenty-one of those games have come against the Maple Leafs, games in which Marchand has 21 points (seven goals, 14 assists).

“They’re always extremely competitive,” Marchand said. “You never know which way the series is going to go. But that’s what you want. That’s what you love about hockey is the competition aspect. They’re real competitors over there, especially the way they’re built right now. So it’s going to be a lot of fun, and that’s what playoffs is about. It’s about the best teams going head-to-head.”

But even though the history favors the Bruins — including having won each of the past six playoff matchups, dating back to the NHL’s expansion era in 1967-68 and each of the four regular-season games in 2023-24 — Marchand is throwing that out the window.

“That means nothing,” he said.

The Maple Leafs bring the No. 2 offense in the NHL into their series, having scored 3.63 goals per game. They were led by Auston Matthews and his 69 goals this season, a new record for him and for the franchise.

“You have to be hard on a guy like that and limit his time and space with the puck,” forward Charlie Coyle said. “He’s really good at getting in position to receive the puck and he’s got linemates who can put it right on his tape for him. You’ve just got to know where he is, especially in our D zone. He likes to loop away after cycling it and kind of find that sweet spot coming down Broadway there in the middle. It’s not just a one-person job.”

Nor is Matthews their only threat.

“They have a lot of great players, skill players, who play hard and can be very dangerous around the net and create scoring opportunities,” forward Charlie Coyle said. “You’ve just got to be aware of who’s out there and who you’re against, who you’re matched up against, and play hard. Also, too, we’ve got to focus on our game and what we do well and when we do that, we trust each other and have that belief in each other, we’re a pretty good hockey team.”

Especially against the Maple Leafs.

Marchand, who grew up in Halifax loving the Maple Leafs, still gets a thrill to see their alumni walking around Scotiabank Arena in the playoffs. And it’s even more special to be on the ice with them, to be competing against them — even more so when the Bruins keep winning.

But that certainly doesn’t mean this series will be easy.

“They’ll be a [heck] of a challenge,” Marchand said.

Sports

NHL sets Round 1 schedule for 2024 Stanley Cup Playoffs – Daily Faceoff

The chase for Lord Stanley’s silver chalice will begin on Saturday.

After what could be described as the most exciting season in NHL history that saw heartbreaks and last-ditch efforts to clinch playoff spots, players and staff now get ready as 16 teams go to battle.

We saw the Vancouver Canucks have a massive year and finish first in the Pacific Division with captain Quinn Hughes leading all defensemen in points. The Winnipeg Jets set a franchise record for most points. The Nashville Predators went on a franchise-record winning streak in order to lock themselves into a Wild Card spot, and the Washington Capitals clinched the last Wild Card spot in the East after a wild finish that saw the Detroit Red Wings and Philadelphia Flyers see their playoff hopes crumble in front of them.

While Auston Matthews missed out on scoring 70 goals, Edmonton Oilers star Connor McDavid and Tampa Bay Lightning standout Nikita Kucherov became the first players since 1990-91 to record 100 assists in a single season. They joined Wayne Gretzky, Mario Lemieux and Bobby Orr as the only players to do so.

With the bracket set, it’s time to expect the unexpected.

Here is the schedule for Round 1 of the 2024 Stanley Cup Playoffs:

Eastern Conference

#A1 Florida Panthers vs. #WC1 Tampa Bay Lightning

| Date | Game | Time |

| Sunday, April 21 | 1. Tampa at Florida | 12:30 p.m. ET |

| Tuesday, April 23 | 2. Tampa at Florida | 7:30 p.m. ET |

| Thursday, April 25 | 3. Florida at Tampa | 7 p.m. ET |

| Saturday, April 27 | 4. Florida at Tampa | 5 p.m. ET |

| Monday, April 29 | 5. Tampa at Florida | TBD |

| Wednesday, May 1 | 6. Florida at Tampa | TBD |

| Saturday, May 4 | 7. Tampa at Florida | TBD |

#A2 Boston Bruins vs. #A3 Toronto Maple Leafs

| Date | Game | Time |

| Saturday, April 20 | 1. Toronto at Boston | 8 p.m. ET |

| Monday, April 22 | 2. Toronto at Boston | 7 p.m. ET |

| Wednesday, April 24 | 3. Boston at Toronto | 7 p.m. ET |

| Saturday, April 27 | 4. Boston at Toronto | 8 p.m. ET |

| Tuesday, April 30 | 5. Toronto at Boston | TBD |

| Thursday, May 2 | 6. Boston at Toronto | TBD |

| Saturday, May 4 | 7. Toronto at Boston | TBD |

#M1 New York Rangers vs. #WC2 Washington Capitals

| Date | Game | Time |

| Sunday, April 21 | 1. Washington at New York | 3 p.m. ET |

| Tuesday, April 23 | 2. Washington at New York | 7 p.m. ET |

| Friday, April 26 | 2. New York at Washington | 7 p.m. ET |

| Sunday, April 28 | 2. New York at Washington | 8 p.m. ET |

| Wednesday, May 1 | 2. Washington at New York | TBD |

| Friday, May 3 | 2. New York at Washington | TBD |

| Sunday, May 5 | 2. Washington at New York | TBD |

#M2 Carolina Hurricanes vs. #M3 New York Islanders

| Date | Game | Time |

| Saturday, April 20 | 1. New York at Carolina | 5 p.m. ET |

| Monday, April 22 | 2. New York at Carolina | 7:30 p.m. ET |

| Thursday, April 25 | 3. Carolina at New York | 7:30 p.m. ET |

| Saturday, April 27 | 4. Carolina at New York | 2 p.m. ET |

| Tuesday, April 30 | 5. New York at Carolina | TBD |

| Thursday, May 2 | 6. Carolina at New York | TBD |

| Saturday, May 4 | 7. New York at Carolina | TBD |

Western Conference

#C1 Dallas Stars vs. #WC2 Vegas Golden Knights

| Date | Game | Time |

| Monday, April 22 | 1. Vegas at Dallas | 9:30 p.m. ET |

| Wednesday, April 24 | 2. Vegas at Dallas | 9:30 p.m. ET |

| Saturday, April 27 | 3. Dallas at Vegas | 10:30 p.m. ET |

| Monday, April 29 | 4. Dallas at Vegas | TBD |

| Wednesday, May 1 | 5. Vegas at Dallas | TBD |

| Friday, May 3 | 6. Dallas at Vegas | TBD |

| Sunday, May 5 | 7. Vegas at Dallas | TBD |

#C2 Winnipeg Jets vs. #C3 Colorado Avalanche

| Date | Game | Time |

| Sunday, April 21 | 1. Colorado at Winnipeg | 7 p.m. ET |

| Tuesday, April 23 | 2. Colorado at Winnipeg | 9:30 p.m. ET |

| Friday, April 26 | 3. Winnipeg at Colorado | 10 p.m. ET |

| Sunday, April 28 | 4. Winnipeg at Colorado | 2:30 p.m. ET |

| Tuesday, April 30 | 5. Colorado at Winnipeg | TBD |

| Thursday, May 2 | 6. Winnipeg at Colorado | TBD |

| Saturday, May 4 | 7. Colorado at Winnipeg | TBD |

#P1 Vancouver Canucks vs. #WC1 Nashville Predators

| Date | Game | Time |

| Sunday, April 21 | 1. Nashville at Vancouver | 10 p.m. ET |

| Tuesday, April 23 | 2. Nashville at Vancouver | 10 p.m. ET |

| Friday, April 26 | 3. Vancouver at Nashville | 7:30 p.m. ET |

| Sunday, April 28 | 4. Vancouver at Nashville | 5 p.m. ET |

| Tuesday, April 30 | 5. Nashville at Vancouver | TBD |

| Friday, May 3 | 6. Vancouver at Nashville | TBD |

| Sunday, May 5 | 7. Nashville at Vancouver | TBD |

#P2 Edmonton Oilers vs. #P3 Los Angeles Kings

| Date | Game | Time |

| Monday, April 22 | 1. Los Angeles at Edmonton | 10 p.m. ET |

| Wednesday, April 24 | 2. Los Angeles at Edmonton | 10 p.m. ET |

| Friday, April 26 | 3. Edmonton at Los Angeles | 10:30 p.m. ET |

| Sunday, April 28 | 4. Edmonton at Los Angeles | 10:30 p.m. ET |

| Wednesday, May 1 | 5. Los Angeles at Edmonton | TBD |

| Friday, May 3 | 6. Edmonton at Los Angeles | TBD |

| Sunday, May 5 | 7. Los Angeles at Edmonton | TBD |

Sports

With matchup vs. Kings decided, Oilers should be confident facing familiar foe – Sportsnet.ca

* public_profileBlurb *

* public_name *

* public_gender *

* public_birthdate *

* public_emailAddress *

* public_address *

* public_phoneNumber *

-

Investment24 hours ago

Investment24 hours agoUK Mulls New Curbs on Outbound Investment Over Security Risks – BNN Bloomberg

-

Sports22 hours ago

Sports22 hours agoAuston Matthews denied 70th goal as depleted Leafs lose last regular-season game – Toronto Sun

-

Media2 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Business21 hours ago

BC short-term rental rules take effect May 1 – CityNews Vancouver

-

Media4 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Art20 hours ago

Collection of First Nations art stolen from Gordon Head home – Times Colonist

-

Investment21 hours ago

Investment21 hours agoBenjamin Bergen: Why would anyone invest in Canada now? – National Post

-

Tech23 hours ago

Tech23 hours agoSave $700 Off This 4K Projector at Amazon While You Still Can – CNET