News

Earthquake Illustrates How Governments and the Media Geopolitically Divide, Denying Kurdistan’s Existence

|

|

Since my mid-20s, I have been studying two things that fascinate me:

- How someone uses language—the words they chose.

- How political self-interest creates and maintains geopolitical divides.

I believe humanitarian aid should be accessible to anyone—much more so than military aid, which Western governments incur debt to provide almost instantaneously—regardless of background, ethnicity, or geographical location.

As someone who constantly studies the “feel of language,” word usage is extremely important to me, especially when it comes to what words are used and omitted. Therefore, knowing the geopolitical divides that exist in the region where last Monday’s devastating earthquake occurred and how it serves Turkey, Syria and the West’s interests, it is not surprising that Western media outlets and governments fail to mention that the autonomous region of Kurdistan was also affected by the earthquake.

Mainstream Western media outlets are referring to the earthquake as the “Turkey-Syria Earthquake,” omitting any mention of Kurds even though Kahramanmaraş and Gaziantep, where the epicenter was located, are not majority Kurdish cities but do have a significant Kurdish population. Further east, cities badly affected by the earthquake, such as Urfa and Diyarbakir, the world’s biggest Kurdish city and where the Kurdish movement to declare an independent Kurdistan was born, have a Kurdish-majority population.

A Moral Compass

I was raised on a Western media diet. (I am not going to say, “I turned out okay.”) It was not until I lived for several years in what is considered “the east” that I saw firsthand the stark contrast in how events are reported. Consequently, I learned that journalism does not have universal ethical standards.

The omission of Kurdistan occurred to me—admittedly not immediately—when Halime Aktürk, a former Kurdish journalist, now an upcoming filmmaker, texted me, “There is no word to describe the pain people are going through in Turkey, Kurdistan and Syria right now.”

I had used Halime’s words as a moral compass before.

The realization, thanks to Halime, that Western media outlets cherry-picked which regions, geo-cultural territories and ethnicities to mention and that Kurdish was never mentioned, while disappointing, was not surprising. This was another example of the Kurdish ethnicity being unrecognized. (READ: erased)

In the West, minds are influenced by media-sold narratives in the following way:

Question: After the massive earthquake, how many people changed their bio emoji flag from Ukraine to Turkey, Syria, or Kurdistan’s flag?

Answer: None.

Why?

Because they were not instructed to do so. (We are social creatures and want to conform to the norm.)

Where are all the social media virtue signalling for earthquake victims? There certainly was immediate social media virtue signalling when Russia invaded Ukraine, when Will Smit slapped Chris Rock during the Oscars, and when Iran’s morality police murdered Mahsa Amini.

Since I am on a tangent, I will ask: Why is the US able to send $115 billion in “aid” (tongue in cheek) to Ukraine yet not find some political heart to lift crippling sanctions on Syria, even temporarily, in the wake of the earthquake?

Geopolitical divides determine whether you are a friend to the US, hence “the West,” or expendable and, in many instances, unrecognized. (e.g., Kurdistan)

Sometimes I feel we are all just selfish pieces of work.

Erdogan’s dichotomy

As I write this, we have, on the one hand, a devasting earthquake that has killed to date more than 33,000 which will inevitably increase and an election scheduled to take place on June 18 in which Turkey’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is running for re-election. (NOTE: Erdogan had said, prior to the earthquake, that the election might be held as early as May 14.) Talk about a dichotomy!

History is instructive. In 2011, twin earthquakes near the Kurdish-majority city of Van led to the deaths of at least 600 people. The Turkish government’s aid provision was “questionable,” as officials decided, on a case-by-case basis, who would receive emergency tents. Moreover, the Turkish government systematically prevented aid from reaching Kurdish-majority cities.

Just as in 2011, Turkey’s issue with its Kurdish population is influencing humanitarian assistance to the February 6th earthquake. In response to Erdogan’s cracked down on visible instances of intra-Kurdish solidarity, Kurdish relief foundations have had to work covertly.

I see Erdogan’s actions as a waste of an opportunity to gain international goodwill, something Turkey desperately needs, especially with Erdogan’s attempts to impose his will on NATO.

However naive, there is an argument to be made that the conditions are right for Turkey and Kurdistan to engage in “earthquake diplomacy” if Erdogan would only see the earthquake as an opportunity to reimage Turkey’s relationship with its Kurdish citizens. (It would be too wild of a stretch to expect Turkey’s government, under Erdogan, also to take a step towards recognizing Kurdistan’s existence.)

I present this thesis because Greek and Turkish foreign ministers George Papandreou and Ismail Cem capitalized on the earthquake in Izmit near Istanbul on August 17, 1999, which killed over 17,000 people, to reconfigure Turkey-Greece relations. Erdogan’s reputation would be bolstered by a new peace initiative in the run-up to Turkey’s Presidential elections.

Unfortunately, the present situation is very different from that of the 1990s. In 1999, Turkey leaned more towards Europe. Today, Erdogan plays the tension card with the Kurds and anyone who opposes his political ideology and has not forcibly shoved Russia away when it invades Ukraine, away like the West has.

Wishful thinking

I know what I just described is wishful thinking. The above-mentioned can only occur if Erdogan is convinced that his self-interest and political survival depend on a dialogue with Turkey’s estimated 14,000,000 Kurds. Unfortunately, it does not. Turkey’s history, and Erdogan’s personal record, have shown that in the aftermath of natural disasters, more, not less, anti-Kurdish repression is likely to follow.

Additionally, Erdogan is astute enough to know that the main opposition party, The National Alliance, has failed to convince voters that they are a force for change. Furthermore, millions of Turkish citizens affected by the earthquake are currently homeless; they are far less likely to be able or want to turn out to vote. When voter turnout is low, hardliners profit; thus, a low turnout would give Erdogan’s right-wing coalition a winning edge.

To show that his self-interests take priority over helping his citizens, in a move meant to bolster rescue efforts and reconstruction Erdogan declared a three-month state of emergency covering the country’s 10 southern provinces hit by the earthquake and then went ahead with Turkish forces bombing Kurdish militia positions in Syria.

Due to Erdogan’s targeting of Kurds, Turkish society has become militarized as well as divisive between Turks and Turkey’s citizens of Kurdish origin. Promoting divisive narratives is an effective political strategy worldwide, not just in the West. Why people keep buying into such narratives has me questioning the nature of humanity.

Furthermore, Erdogan has undermined US-Turkey relations because Kurds in Syria are America’s main ally in a multinational coalition against ISIS, which is why he accuses the West of enabling terrorism, which is why I believe no US administration while Erdogan has been in power, has made any serious attempts to mediate an end to Turkey’s war on Kurds. Optics plays a critical role when it comes to navigating when and how to cross geopolitical divides.

The Turkish government has its self-interests. The US government, which undeniably leads the West, has its self-interests. Here is another dichotomy, if someone sins differently than you, who are you to judge them? The world is full of contradictory truths that keep our discourses alive.

For the moment, the earthquake has relieved much of the mounting political tension for upcoming elections. Besides the blatant xenophobic resentment of Kurdish and Syrian refugees, Turks of all political stripes were finger-pointing at each other regarding Turkey’s hyperinflation, censorship, high housing costs, and security issues. Once the impact of this tragic event is over—reporting on the earthquake is already dimming—becoming I am sure Erdogan will return to evangelizing highly nationalistic and divisive policies that he feels will win him the election.

Puzzling

It is puzzling that Erdogan still fails to recognize the damage his government’s treatment of the Kurds has done to Turkey’s international standing as a democracy and an economic leader. While the US most likely will not exert its diplomatic and economic leverage on Turkey in the wake of this week’s natural disaster to advance Turkey socially and economically, which ironically would serve its interests, this does not mean Erdogan cannot put aside geopolitical and cultural divides and view the earthquake as a historic opportunity for Turkey to change course, thus creating a legacy of peace rather than oppression.

Unfortunately, as with most political leaders, Erdogan’s story is about power. Every politician wants to be seen as a powerful leader in the face of a problem, especially during a crisis. However, millions of people are homeless, looming medical disasters, and a death toll expected to surpass 50,000, according to the UN relief chief Martin Griffiths. This natural disaster is beyond Erdogan’s power.

However, putting aside differences—Yes, I am putting it mildly—is not beyond his power. It is well with his power to do what’s right for all those within Turkey’s border and its surrounding neighbours who have seen their lives destroyed in a matter of moments. I hope Erdogan soon sees compassion as another avenue to serve his self-interest at home and abroad.

____________________________________________

Nick Kossovan, a self-described connoisseur of human psychology, writes about what’s on his mind from Toronto. You can follow Nick on Twitter and Instagram @NKossovan

News

Gas prices: Why drivers in Eastern Canada could pay more – CTV News

Drivers in Eastern Canada could see big increases in gas prices because of various factors, especially the higher cost of the summer blend, industry analysts say.

Patrick De Haan, head of petroleum analysis at fuel savings website GasBuddy in Chicago, predicts a big gas hike for the eastern portions of Canada including Ontario, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick and Nova Scotia over the next several days, while some areas in the Maritimes have already seen the increases.

“Unfortunately, for … really a third of Canada, we’re likely to see a big jump in what (motorists) are seeing at the pump,” he said in a video interview with CTVNews.ca. “Gas prices could rise in excess of 10 cents a litre. All of that having to do with yesterday’s switchover to summer gasoline.”

Gas prices may continue to increase for the next week or two, De Haan said. “But I think the end is near for the seasonal increases and we should start to see prices decreasing potentially by May (long weekend).”

Dan McTeague, president of Canadians for Affordable Energy, also forecasts gas price hikes.

Ontario and Quebec will see a 14-cent-per-litre increase overnight Thursday, he said on Wednesday. He predicts the price per litre will rise to $1.79 in cities across Ontario, the highest since Aug. 2, 2022. In Quebec, he expects the price per litre will increase to $1.88.

McTeague attributes this week’s increase to the higher cost of summer blended gasoline.

De Haan, meanwhile, observed the following changes in prices across Canada compared to a week ago:

- Prices in Saskatchewan are flat;

- Manitoba prices are up about a half a penny per litre;

- Alberta is down seven-tenths of a penny per litre;

- P.E.I. is up about 1.2 cents a litre;

- B.C. is up about 2.5 cents a litre;

- Nova Scotia is up three cents a litre;

- Quebec is up 3.5 cents a litre;

- Ontario is up 4.5 cents a litre;

- New Brunswick is up five cents a litre;

- Newfoundland is up seven cents a litre.

Factors behind spikes

“Some gas stations have already raised their price, in essence, but some others may not for the next day or two,” De Haan said. “So over the next several days, the averages will continue to rise as more stations raise their price. … Most of the increase is happening right now in the eastern portions of Canada.”

The summer gas switch will have “just a one-time impact” on gas prices, De Haan said.

More drivers are on the road, creating rising demand for gas as temperatures warm up, and refiners are wrapping up maintenance ahead of the start of the summer driving season. “While they do that maintenance, they’re generally not able to supply as much gasoline into the market,” De Haan explained.

Despite tensions between Iran and Israel, the recent attack has had “little impact” on the price of oil, De Haan said.

“Last week, oil prices did climb to their highest level (in) six months as Iran suggested it was going to attack Israel,” he said. “Now that those attacks have happened and they largely have been unsuccessful, the price of oil is actually declining.”

Third major spike in 2024

Michael Manjuris, professor and chair of global management studies at Toronto Metropolitan University, said the new gas price increase would be the third major spike across Canada since the start of the year.

One factor is the price of crude oil worldwide has risen 15 per cent since Jan. 1, Manjuris said.

The federal carbon tax increase of about 3.3 cents per litre on April 1 is also another reason for the big jolts in gas prices, he added.

Although the switch to summer blend fuels typically happens every year, Manjuris said, it will be more painful economically because it’s on top of the two other major increases this year. “This increase now will cause the overall price of gasoline to be very high,” he said in a video interview with CTVNews.ca. “We haven’t seen these kinds of prices since 2022.”

Manjuris believes gas prices will continue to rise through the summer as global demand for oil begins to grow. “That’s because we’re seeing increased economic activity in China, in the United States and in Europe,” he explained. “When those things all come together, price of crude oil starts to go up. … So I’m predicting that because of demand increasing, price of gasoline in Canada will also go up in the summer months. I’m going to suggest three to five cents a litre will be the peak before it starts to come back down.”

Regional differences

The West Coast and Prairies won’t have any gas price hikes coming soon because they already transitioned to summer gasoline, De Haan said. “So this is something associated with the switchover, which happens last in the eastern parts of Canada,” he explained.

In addition, he said regions have “subtle differences” in their supplies of gasoline.

“Supplies of winter gasoline in the eastern portions of Canada was rather lavish and so discounts were significant,” he said. “But now that the eastern part of Canada is rolling over to relatively tight supplies of summer gasoline, this is something much more impactful. That is other areas of Canada did roll over to summer gasoline, but they did not have necessarily the big discounts that would associate with the big price swing that we’re seeing.”

With files from CP24.com Journalist Codi Wilson

News

For its next trick, Ottawa must unload the $34B Trans Mountain pipeline. It won't be easy – CBC.ca

In her budget speech to the House of Commons on Tuesday, Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland took a moment to celebrate the finishing touch on expansion of the Trans Mountain oil pipeline.

The controversial project has been plagued by delays and massive cost overruns, but Freeland instead focused on its completion, highlighting the: “talented tradespeople and the brilliant engineers who, last Thursday, made the final weld, known as the golden weld, on a great national project.”

For all the difficulties with developing and building TMX, Freeland still faces another major hurdle that is sure to prove contentious — choosing when to sell it, who gets to buy it, and for how much.

An upcoming election and more than $34 billion in construction costs are raising the stakes.

Ottawa bought the project when it was on the verge of falling apart — before there was ever a shovel in the ground — in the face of legal, political and regulatory challenges.

The federal government has long vowed to sell the project (including at least a partial ownership stake to Indigenous groups) once construction was complete. That milestone has now been reached.

But the move will no doubt open a Pandora’s box, says Daniel Béland, the director of the McGill University Institute for the Study of Canada and a professor in the department of political science.

He says any potential deal will face intense scrutiny considering the election is due before the fall of 2025 and, most notably, because the actual sale price is expected to be far lower than the cost to actually build the pipeline.

“They were in a hot spot when they bought it back in 2018. They are still in a hot spot,” said Béland.

How the governing Liberals handle Trans Mountain could impact how voters view the Liberal party’s handling of financial, economic, Indigenous, and environmental issues.

“There’s risk either way. If you sell it really fast, but you sell it at the price that is considered to be quite low, then you might be accused of just getting rid of it for political reasons but not having the interest of taxpayers in mind,” he said.

“But, if you wait and you don’t sell it, then you might be accused of being basically permanently involved or trying to be permanently involved in that sector of the economy in a way that many people, even people who are more conservative, may find inappropriate.”

Deep discount

There has always been interest in buying it, including from Stephen Mason, the managing director of Project Reconciliation, a Calgary-based organization which aims to use a potential ownership stake to benefit Indigenous communities.

Nearly five years ago, Mason walked into then-federal finance minister Bill Morneau’s office in Ottawa and made an offer to purchase Trans Mountain before construction had even begun on its expansion, which will transport more oil from Alberta to the British Columbia coast.

Morneau was interested, he says, but the project wasn’t for sale until the new pipeline was built.

Much has changed since that meeting in July 2019, including the ballooning cost of Trans Mountain to more than $34 billion (compared to an original estimate of about $7.3 billion) and numerous delays in construction.

Mason is still pursuing ownership. He won’t discuss numbers, but suspects Trans Mountain is worth far less than $34 billion.

“My intuition is telling me that it’s going to be a fairly significant writedown,” he said. “I’m not sure the Liberal government wants to get into a public recognition of what the writedown is ahead of the election, but that is just … my speculation.”

New tolls

A critical factor in the timing and price of a potential sale is a dispute over how much oil companies will have to pay to actually use the new pipeline.

Several large oil producers signed long-term contracts to use 80 per cent of the pipeline. However, as construction costs have soared, so too have the tolls that companies will have to pay.

Those companies have balked at the higher rates arguing they shouldn’t have to bear the “extreme magnitude” of construction overruns. The Canada Energy Regulator has scheduled a hearing for September, at the earliest, to resolve the issue.

For now, the regulator has set an interim toll of $11.46 for every barrel of oil moved down the line. That price includes a fixed amount of $10.88 and a variable portion of $0.58. The fixed amount is nearly double what Trans Mountain estimated it would be in 2017.

“There’s no way that you can have tolls high enough on TMX to cover a $34 billion budget,” said Rory Johnston, an energy researcher and founder of the Commodity Context newsletter, who describes the cost overruns on the project compared to the original estimates as “gigantic.”

Lessons could be learned on how the Trans Mountain expansion pipeline was developed and built, says company CFO Mark Maki.

He doesn’t expect the final tolls to be much higher than the interim amount because, otherwise, the pipeline could become too expensive for oil companies to want to use. Based on the interim tolls, Johnston expects the federal government to likely only recover about half of the money it spent to buy and build Trans Mountain.

“There’s no way anyone would pay the full cost of the pipeline because the tolls don’t support it. You’re going to need to discount it. You’re going to need to take a haircut of at least 50 per cent of this pipeline,” he said.

The federal government currently owns the original Trans Mountain pipeline, built in 1953, the now-completed expansion and related facilities including storage tanks and an export terminal.

Potential buyers

The federal government has looked at offering an equity stake to the more than 120 Western Canadian Indigenous communities whose lands are located along the pipeline route, while finding a different buyer to be the majority owner.

Besides Project Reconciliation, other potential buyers include a partnership between the Western Indigenous Pipeline Group (WIPG) and Pembina Pipelines.

The group has the support from about 40 Indigenous communities and hopes to purchase the project within the next year, said Michael Lebourdais, an WIPG director and chief of Whispering Pines/Clinton Indian Band, located near Kamloops, B.C.

Those communities have to live with the environmental risk of a spill, so they should benefit financially from the pipeline, he says.

Pension funds and other institutions could pursue ownership too.

“There will be buyers. I’m not sure that they’ll be willing to pay the full cost of construction but I think there’ll be buyers for sure,” said Jackie Forrest, executive director of the ARC Energy Research Institute.

The federal government will likely highlight the overall economic benefits of the new pipeline and the expected role of Indigenous communities in ownership, experts say, as a way to defend against criticism if the eventual sale price is low.

In her Tuesday speech, Freeland was already promoting the pipeline’s expected financial boost by highlighting the Bank of Canada’s recent estimate that the new Trans Mountain expansion will add one-quarter of a percentage point to Canada’s GDP in the second quarter.

News

14 suspects arrested in grandparents scam targeting seniors across Canada: OPP – CP24

An interprovincial investigation into an “emergency grandparents scam” that targeted seniors across Canada has led to the arrest of 14 suspects, Ontario Provincial Police say.

Details of the investigation, dubbed Project Sharp, were announced at a news conference in Scarborough on Thursday morning.

Police said 56 charges have been laid against the suspects, who were all arrested in the Montreal area.

According to police, since January, investigators identified 126 victims who were defrauded out of a total of $739,000. Fifteen of those victims were defrauded on multiple occasions, police said, resulting in the loss of an additional $200,000.

The victims, who range in age from 46 to 95, were targeted based on the fact that they had landline telephones, police said. While people across the country were defrauded, police said, the majority resided in Ontario.

Police said four of the 14 arrested in the fraud remain in custody while the other 10 have been released on bail. The charges they face include involvement in organized crime groups, extortion, impersonating a police officer, and fraud, police said.

OPP Det.-Insp. Sean Chatland told reporters Thursday that the police service began looking into an “organized crime group” believed to be involved in fraud during an intelligence probe in September 2022.

By February 2023, Chatland said the probe was formalized into an OPP-led joint forces investigation involving police services in both Ontario and Quebec.

“This organized crime group demonstrated a deliberate and methodical approach in exploiting victims. They operated out of Ontario and Quebec, utilizing emergency grandparents scams on victims across Canada,” Chatland said.

“They would impersonate police officers, judges, lawyers, and loved ones, preying on grandparents who believed they were trying to help family members in trouble.”

He said in many cases, the suspects utilized “money mules” or couriers to collect large sums of money from the victims.

This is a breaking news story. More details to come.

-

Tech18 hours ago

Tech18 hours agoCytiva Showcases Single-Use Mixing System at INTERPHEX 2024 – BioPharm International

-

Science24 hours ago

Science24 hours agoNasa confirms metal chunk that crashed into Florida home was space junk

-

News20 hours ago

Tim Hortons says 'technical errors' falsely told people they won $55K boat in Roll Up To Win promo – CBC.ca

-

Investment24 hours ago

Investment24 hours agoBill Morneau slams Freeland’s budget as a threat to investment, economic growth

-

Politics23 hours ago

Politics23 hours agoFlorida's Bob Graham dead at 87: A leader who looked beyond politics, served ordinary folks – Toronto Star

-

Health14 hours ago

Health14 hours agoSupervised consumption sites urgently needed, says study – Sudbury.com

-

Science23 hours ago

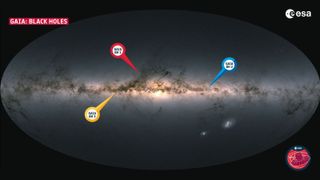

Science23 hours agoRecord breaker! Milky Way's most monstrous stellar-mass black hole is sleeping giant lurking close to Earth (Video) – Space.com

-

Tech20 hours ago

Tech20 hours agoAaron Sluchinski adds Kyle Doering to lineup for next season – Sportsnet.ca