For the past decade Ethiopia has boasted of one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, welcoming billions of dollars in foreign direct investment from the U.S. and China and lifting more than 20 million people out of poverty.

Now, a monthlong civil war, coronavirus lockdowns and historic locust infestations have left the once-golden economy stumbling, as it grapples with one of Africa’s most perilous debt loads, soaring inflation and the risk of a protracted insurgency.

Fighting between government forces and the rebel Tigray People’s Liberation Front has paralyzed much of northern Ethiopia, shaking a nation of 110 million people long seen as a symbol of stability in a volatile region.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed claimed victory after taking a rebel stronghold.

Photo: Mulugeta Ayene/Associated Press

Prime Minister

Abiy Ahmed

has claimed victory after taking the rebel stronghold of Mekelle, but TPLF fighters have retreated into remote mountainous regions and vow to continue fighting.

Roads, bridges, a power plant and a sugar mill have been destroyed. The Ethiopian currency has sunk 20% against the dollar this year, suppressing purchasing power across a nation where millions of people are already dependent on food aid.

Foreign companies have been caught in the crossfire. Production at three textile factories in Tigray that supply Swedish fashion chain

H&M

has been halted. China has evacuated 500 of its nationals who were working in Tigray.

“What is clear is that this conflict will leave lasting damage on Ethiopia’s economy,” said

Alex de Waal,

executive director of the Massachusetts-based World Peace Foundation. “Ethiopia is in turmoil. The indication from the government that the war is over is not correct.”

The country’s state-led model of development helped expand the economy from $10 billion in 2004 to nearly $100 billion last year.

For most of that period, the TPLF were the country’s dominant political force, until Mr. Ahmed came to power in 2018 on a promise to liberalize politics and the state-controlled economy. Tensions between Mr. Ahmed’s government and the TPLF exploded into armed conflict early last month.

The conflict is the latest in a series of economic shocks to Ethiopia, each compounding one another.

A man stands near the site of a massacre last month on the outskirts of Mai Kadra, Ethiopia.

Photo: eduardo soteras/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

The agriculture sector, which accounts for nearly half of the Ethiopian economy, has recorded its worst harvest in decades after locusts destroyed some 200,000 hectares of farmland, leaving more than eight million people in need of food assistance. The U.S.-funded Famine Early Warning Systems Network said recently that the conflict could complicate efforts to avert another infestation.

The fighting has closed two of the busiest border crossings between Ethiopia and Sudan, hobbling the trade of commodities from grains to cooking oil. Across swaths of Tigray, towns have emptied of people and farmers have abandoned vast tracts of land.

Economic growth is expected to slump to 1.9% in 2020 from 10% last year, the worst performance in 20 years. The government expects as many as 2.5 million jobs could be lost in the fast-growing textiles industry after travel restrictions and declining foreign demand combined to worsen an unemployment rate that is more than 40%.

Economists are split over whether a quick recovery could yet save many of those jobs. The U.K. and Germany set up a $6.5 million fund last month to try to save Ethiopian jobs.

Companies that had turned to Ethiopia’s cheap manufacturing in the wake of rising labor costs in Asia are cutting jobs. Some 7,000 jobs have already been lost at Hawassa Industrial Park, a sprawling Chinese-built complex located in central Ethiopia that makes a variety of goods, including textiles.

“Some companies have recorded up to a 90% decline in orders,” said

Belay Hailemichael,

chief executive of the park.

A satellite image of Mekelle, capital of the Tigray region of Ethiopia.

Photo: Maxar/Associated Press

Tourism and business travel, another fast-growing sector in a country that has invested billions to become a regional transport hub, have been hit especially hard.

Daniel Berhanu,

manager of the Addis Ababa Hotel Owners Association, said that almost 80% of hotels in Addis Ababa had closed after the coronavirus restrictions, and the war is now choking off the recovery. “We are fighting for our very existence,” he said.

Travel restrictions have sent Ethiopian Airlines, a symbol of Ethiopia’s breakneck growth, reeling, forced to idle much of its fleet this year as flights were cut by one-third. Now, the conflict with the TPLF has compelled the carrier to suspend a number of domestic routes after rebels fired volleys of rockets.

Fighting in Ethiopia between government forces and the rebel-run Tigray People’s Liberation Front has killed thousands and forced tens of thousands to flee to neighboring Sudan. WSJ’s Joe Parkinson explains what’s behind the conflict and what’s at stake. Photo: Eduardo Soteras/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images[object Object]

Ethiopia’s government says its economy has responded well to the challenges and predictions of a prolonged insurgency are wrong. “The TPLF does not have the support of the Tigrayan people,” said a spokesman for the prime minister.

Many businesses in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s bustling highland capital, see economic momentum returning rapidly.

Shopping malls, restaurants and hotels are bustling after authorities lifted social-distancing measures in the summer. “In business, instability is your worst nightmare, but hopefully next year things will be much better,” said

Henok Assefa,

managing partner of business advisory Precise Consult.

Aubrey Hruby,

a senior fellow at the Washington-based Atlantic Council, said that even if an insurgency rumbles in the north, the overall investment story in Ethiopia should remain attractive for a country that has successfully courted foreign investment in textiles, energy, tourism and travel and has plans to further liberalize telecoms, banking and insurance.

SHARE YOUR THOUGHTS

What concerns do you have about the humanitarian situation in Ethiopia? Join the conversation below.

“It’s a short-term disincentive to investment…I remain optimistic,” she said.

A key test will be investor appetite for Ethiopia’s liberalization of the telecom sector, another centerpiece of Mr. Ahmed’s overhaul plan. The government says it is on track to sell a minority stake in Ethio Telecom next year and that tendering for two new licenses for international companies to operate in the country will go ahead. But telecom industry executives fear the fighting could lead to delays and weaken investor interest.

Meanwhile, the conflict—including providing humanitarian assistance for one million people displaced by the fighting—and pandemic-related health costs will add to Ethiopia’s fast-rising debt pile, which has swelled from 40% in 2010 to 60% this year.

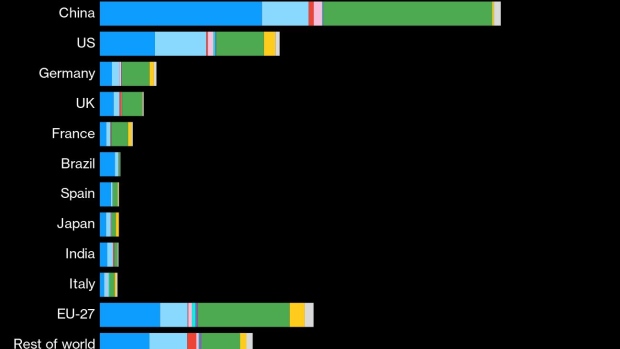

China, Ethiopia’s largest creditor, accounts for more than 40% of external debt, and it has funded a network of roads, power plants and railways, according to the China Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University.

Ethiopian refugees who fled the Tigray conflict line up at the Um Raquba camp in eastern Sudan.

Photo: yasuyoshi chiba/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

The International Monetary Fund has warned that Ethiopia is one of two African nations at high risk of debt distress. The other, Zambia, is already in technical default.

Civilians caught in the fighting are already paying the price.

Awad Kareem

was forced to abandon his gasoline station and flee when hostilities erupted.

“I heard that young men were being conscripted to take part in the fighting, and I was scared,” he said. Now in a makeshift refugee camp in Sudan, he’s unsure when he will get home, and if his business will still be there. “We left behind an empty town,” he said.

—

Yohannes Anberbir

contributed to this article.

Write to Nicholas Bariyo at nicholas.bariyo@wsj.com and Joe Parkinson at joe.parkinson@wsj.com