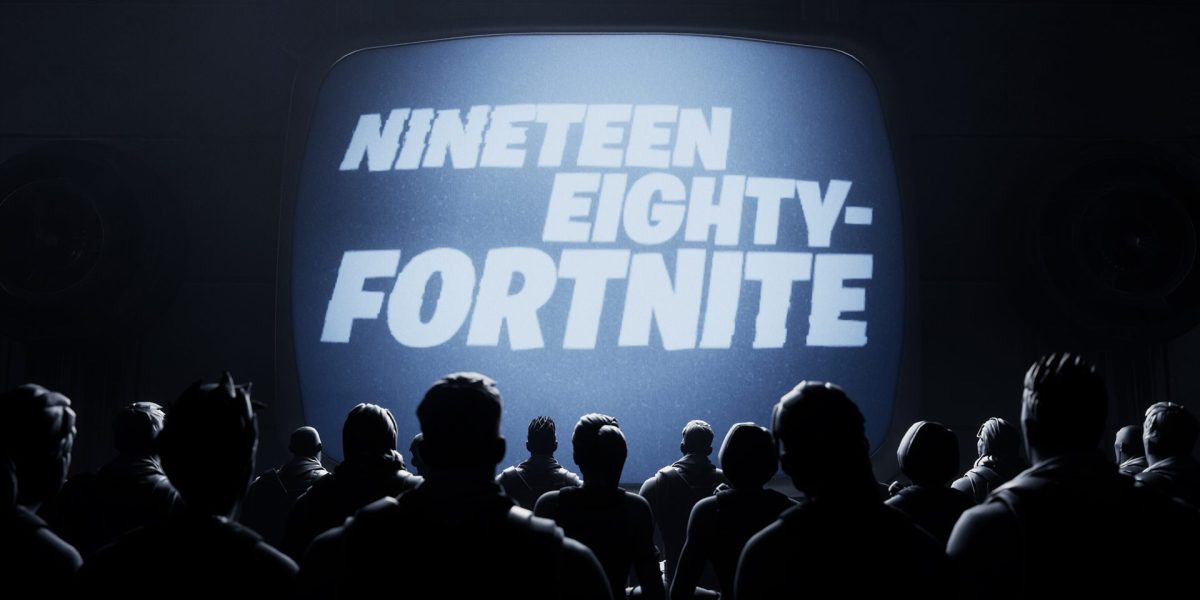

When the news broke yesterday that Apple and Google banned Epic’s super-popular game Fortnite from their app stores, most people focused on the bans — how could this happen? — and Epic’s nearly instant, comprehensive lawsuits against both tech giants. Given how quickly everything was moving, they might have missed the specific reasons Apple and Google gave for the bans.

In prepared statements, Apple claimed its App Store “guidelines create a level playing field for all developers and make the store safe for all users.” Google used nearly identical language, saying that its Play Store has “consistent policies that are fair to developers and keep the store safe for users.” Both companies suggested Epic violated their policies by offering an in-app route to purchase Fortnite’s “V-Bucks” currency at a discounted price — something that’s currently possible on Mac, PC, PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and Nintendo Switch platforms, or in physical stores with Fortnite gift cards.

These might just be the companies’ canned explanations, but Apple and Google may well die on the hill fighting Epic over supposed developer fairness and user safety. Epic isn’t just any old developer; it’s a 29-year-old company with offices across North America, Europe, and Asia, relied upon by hundreds of developers for the widely respected Unreal Engine. It has operated the developer-centric Unreal Engine Marketplace for six years and the consumer-focused Epic Games Store for nearly two years. Both charge third-party developers a 12% fee — a “permanent rate” that Epic notes “covers the operating costs of the store and makes us a profit.” It has been generous to developers, using its profits to help them pay off student loans and awarding MegaGrants to create content.

It’s therefore no shock that Epic’s view of what’s “fair to developers” isn’t the same as Apple’s or Google’s. The larger tech companies generally take a 30% cut of all app purchases and in-app revenues generated by their developers; Apple goes further than Google, preventing iOS users from installing apps that weren’t downloaded from its own App Store. Too many developers to count have complained about these 30% cuts as unfair and damaging to their businesses, but Apple generally brushes aside their complaints, suggesting that like it or not, everyone’s playing by the same rules. It doesn’t take much to conclude that 12% (or any number lower than 30%) will be more “fair to developers” than the status quo.

Apple’s claim of a supposedly “level playing field” for app developers is equally questionable. The iOS App Store and Google Play Store might offer the same terms to a two-woman independent developer and a company with thousands of engineers, but if they’re selling identical apps, everyone knows the big company will roll over the indie repeatedly on that playing field due to its other resources. It can rig search results with paid ads, acquire customers with cross-promotions, and brute-force updates to copy innovations with comparative impunity.

There’s also no shortage of evidence that certain developers have won different treatment by leveraging existing relationships, size, or legal threats to force either exceptions or changes to the rules. A Congressional antitrust investigation revealed that Apple agreed in 2016 to reduce its cut to 15% for long-time holdout Amazon — a concession undermining Apple’s claim that all App Store developers are treated equally. On the other hand, Epic says that Google used its power to force OnePlus and LG to kill deals that would have pre-installed Fortnite on Android phones using an Epic Games app, rather than the Google Play Store. Sideloading apps is permitted on Android, but Google is apparently willing to aggressively discourage it, citing trust issues.

Is either platform holder actually making these moves to “keep the store safe for users?” From a 30,000-foot perspective, sure. If Apple or Google controls the payment system, screens every app, manages every update, and acts as an intermediary for user-developer disputes, it can theoretically guarantee a safe experience. But so can experienced developers. Amazon has been selling products online since 1995 — years before Apple launched its modern online store (1997) and opened its first brick-and-mortar locations (2001) — so it’s not as if consumers can’t trust its infrastructure. Epic has been selling its own software since 1991 and content from others for years. Everyone else has access to alternate but well-trusted payment systems that merely deny the platform holders a cut.

What sort of additional safety are Apple and Google really providing here? At best, the promise that they will serve as a better intermediary than developers — not necessarily these developers, but less established or scrupulous ones — over time. In Apple’s case, there’s also some likelihood that added screening will keep malware or other issues from impacting users. Google has had at best mixed results and doesn’t seem to have done a very good job with this, but it’s trying, while Apple has achieved at least some of its success here by becoming stricter, forbidding things it previously either permitted or didn’t explicitly stop.

As I’ve said before, the root of Apple’s problem is its obsession with control and exorbitant profits, which Google has tried to emulate with its Play Store to the disadvantage of both companies’ users and developers. Thanks to Epic’s credibility and Fortnite’s popularity, Epic is ideally suited to challenge these platform holders in the courts of both law and public opinion, hopefully forcing the sort of large-scale changes that smaller developers have struggled for years to achieve — plus the benefits to consumers that will follow from greater competition and more reasonable prices.