Unfortunately the government lacks authority just when it needs it. By so gravely mishandling the recent social unrest, it lost the public’s trust. It now struggles to convince people that it is doing all it should to stop the disease. Some hospital workers have gone on strike, demanding a complete closure of the border with the mainland (see article). Others are furious about the shortage of masks. A more credible government might advise people that they do not need to wear one unless they are ill. But such advice would be scorned in Hong Kong. It has run out of masks because its government has run out of trust.

Economy

Hong Kong’s economy is in peril, but its financial system is not – The Economist

AS THEY REPAY their debt to society, many Hong Kong prisoners are put to work making useful items like road signs, uniforms, furniture—and the surgical masks that now obscure the faces of almost everyone on the city’s subdued streets. To help stop the spread of the Wuhan coronavirus, which has infected over 28,000 people worldwide, prisoners will now be employed round the clock, boosting mask production by as much as 60%.

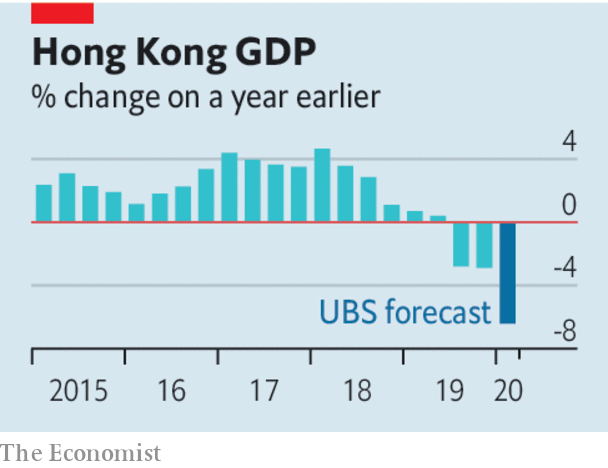

That, sadly, is one of the few economic ventures that is still expanding in this thrice-struck city. Its GDP shrank last year for the first time in a decade, thanks to the trade war and anti-government protests. The coronavirus now poses a third threat. Some economists have slashed their growth forecasts for Hong Kong by more than for the mainland (see article).

Hong Kong’s economic fate is of international concern. Vast sums of global capital flow in and out of its asset markets and its border-straddling banks. Some speculators now fret about its financial resilience, noting its exorbitant property market, where prices have tripled in ten years, and top-heavy banking system, which has assets worth 845% of GDP. As protests intensified last year, bets against Hong Kong’s currency, which has been firmly pegged to the dollar since 1983, became unusually popular. The city’s monetary officials proclaimed no reason to worry. But that is the kind of thing you have to say only when others suspect that it is not entirely true.

The fear about Hong Kong’s domestic economy is warranted. Much of the city’s livelihood depends on the economic virtues of openness and propinquity. It excels as both an entrepot and a rendezvous, where people from far-flung places can gather in jam-packed proximity. It thrives on human interaction. But so does the virus. Thus efforts to impede the disease, such as discouraging visitors and gatherings, also paralyse the economy.

These justifiable fears for Hong Kong’s local economy do not, however, extend to its banks or its currency. Precisely because its property market and its financial system have become partially divorced from its local economy, they are somewhat insulated from domestic travails. And its banks have grown so big partly because they serve mainland firms with global ambitions, whose fortunes are decided outside Hong Kong. Most lenders are well-capitalised and mortgage lending is tightly controlled.

Hong Kong’s currency peg is also heavily fortified. Foreign-exchange reserves are twice as large as the money supply, narrowly defined. In principle, the banks would run out of Hong Kong dollars to sell to the monetary authority before it would run out of American dollars with which to buy them. In practice, interest rates would spike long before then.

That would make holding the currency more rewarding and betting against it more expensive. It would also inflict pain on the economy. For the peg to survive, the government would have to endure the agony longer than speculators could endure the expense. During the Asian financial crisis in 1997 (when overnight interest rates briefly reached 280%), Hong Kong showed how far it was willing to go. The peg’s survival back then has made it more likely to survive future tests, too. Hong Kong has built a reputation for competence and integrity with international investors. What a shame that the government has squandered its reputation for those very qualities with its own population.■

This article appeared in the Leaders section of the print edition under the headline “Hong Kong’s economy is in peril, but its financial system is not”

Economy

Trump’s victory sparks concerns over ripple effect on Canadian economy

As Canadians wake up to news that Donald Trump will return to the White House, the president-elect’s protectionist stance is casting a spotlight on what effect his second term will have on Canada-U.S. economic ties.

Some Canadian business leaders have expressed worry over Trump’s promise to introduce a universal 10 per cent tariff on all American imports.

A Canadian Chamber of Commerce report released last month suggested those tariffs would shrink the Canadian economy, resulting in around $30 billion per year in economic costs.

More than 77 per cent of Canadian exports go to the U.S.

Canada’s manufacturing sector faces the biggest risk should Trump push forward on imposing broad tariffs, said Canadian Manufacturers and Exporters president and CEO Dennis Darby. He said the sector is the “most trade-exposed” within Canada.

“It’s in the U.S.’s best interest, it’s in our best interest, but most importantly for consumers across North America, that we’re able to trade goods, materials, ingredients, as we have under the trade agreements,” Darby said in an interview.

“It’s a more complex or complicated outcome than it would have been with the Democrats, but we’ve had to deal with this before and we’re going to do our best to deal with it again.”

American economists have also warned Trump’s plan could cause inflation and possibly a recession, which could have ripple effects in Canada.

It’s consumers who will ultimately feel the burden of any inflationary effect caused by broad tariffs, said Darby.

“A tariff tends to raise costs, and it ultimately raises prices, so that’s something that we have to be prepared for,” he said.

“It could tilt production mandates. A tariff makes goods more expensive, but on the same token, it also will make inputs for the U.S. more expensive.”

A report last month by TD economist Marc Ercolao said research shows a full-scale implementation of Trump’s tariff plan could lead to a near-five per cent reduction in Canadian export volumes to the U.S. by early-2027, relative to current baseline forecasts.

Retaliation by Canada would also increase costs for domestic producers, and push import volumes lower in the process.

“Slowing import activity mitigates some of the negative net trade impact on total GDP enough to avoid a technical recession, but still produces a period of extended stagnation through 2025 and 2026,” Ercolao said.

Since the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement came into effect in 2020, trade between Canada and the U.S. has surged by 46 per cent, according to the Toronto Region Board of Trade.

With that deal is up for review in 2026, Canadian Chamber of Commerce president and CEO Candace Laing said the Canadian government “must collaborate effectively with the Trump administration to preserve and strengthen our bilateral economic partnership.”

“With an impressive $3.6 billion in daily trade, Canada and the United States are each other’s closest international partners. The secure and efficient flow of goods and people across our border … remains essential for the economies of both countries,” she said in a statement.

“By resisting tariffs and trade barriers that will only raise prices and hurt consumers in both countries, Canada and the United States can strengthen resilient cross-border supply chains that enhance our shared economic security.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 6, 2024.

The Canadian Press. All rights reserved.

Economy

September merchandise trade deficit narrows to $1.3 billion: Statistics Canada

OTTAWA – Statistics Canada says the country’s merchandise trade deficit narrowed to $1.3 billion in September as imports fell more than exports.

The result compared with a revised deficit of $1.5 billion for August. The initial estimate for August released last month had shown a deficit of $1.1 billion.

Statistics Canada says the results for September came as total exports edged down 0.1 per cent to $63.9 billion.

Exports of metal and non-metallic mineral products fell 5.4 per cent as exports of unwrought gold, silver, and platinum group metals, and their alloys, decreased 15.4 per cent. Exports of energy products dropped 2.6 per cent as lower prices weighed on crude oil exports.

Meanwhile, imports for September fell 0.4 per cent to $65.1 billion as imports of metal and non-metallic mineral products dropped 12.7 per cent.

In volume terms, total exports rose 1.4 per cent in September while total imports were essentially unchanged in September.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Nov. 5, 2024.

The Canadian Press. All rights reserved.

Economy

How will the U.S. election impact the Canadian economy? – BNN Bloomberg

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

How will the U.S. election impact the Canadian economy? BNN Bloomberg

Source link

-

News13 hours ago

Alberta aims to add two seats to legislature, bringing total to 89 for next election

-

News21 hours ago

Trump snaps at reporter when asked about abortion: ‘Stop talking about it’

-

News21 hours ago

UN refugee chief: Canada cutbacks can avoid anti-immigrant backlash

-

News13 hours ago

Pembina Pipeline earnings rise year over year to $385 million in third quarter

-

News21 hours ago

Party leaders pay tribute following death of retired senator Murray Sinclair

-

News21 hours ago

Canadians remember Quincy Jones

-

News13 hours ago

‘He violated me’: Women tell sex assault trial Regina chiropractor pulled breasts

-

News21 hours ago

Beyoncé channels Pamela Anderson in ‘Baywatch’ for Halloween video asking viewers to vote