For a country with such a severe shortage of housing, the way Canada builds homes hasn’t changed that much since the country was founded.

Workers arrive on site with building materials they assemble piece by piece, a little like how cars were built until Ford invented the assembly line more than a century ago.

The federal government is aware more productive methods are needed so it’s pushing for modular construction, where homes are fully or partially assembled in a factory before onsite installation.

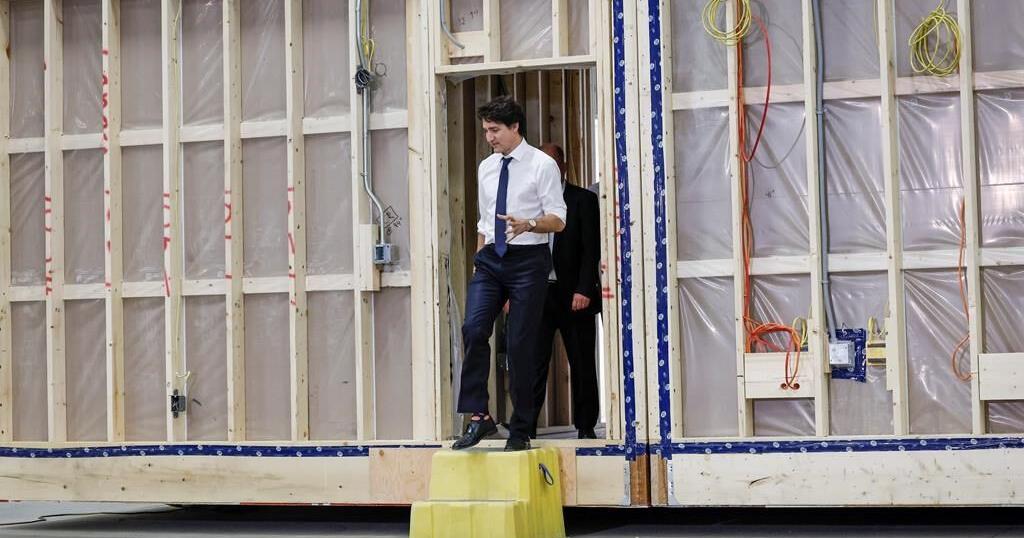

“When I talk about making it faster to build homes, modular housing is a big part of it,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said in a July statement.

The process can get housing built anywhere from 20 to 50 per cent faster, according to a report from consulting firm McKinsey, while also cutting down on neighbourhood disruption, reducing waste, requiring fewer workers, and potentially being upwards of 20 per cent cheaper.

To speed up adoption, the government is earmarking $500 million in loans for apartment builders that use modular construction and other innovative techniques. It’s also providing funding for local innovative housing solutions and research to develop new ones, and has committed to reducing regulatory barriers and standardizing designs.

But while some initiatives are underway, industry insiders say much more is needed to create a foundation for the streamlined building technique to grow from its paltry two per cent of the market.

“It is not as simple as, oh, well, somebody just thought of modular housing, so let’s do it,” said Kevin Lee, chief executive of the Canadian Home Builders’ Association.

Along with targeted support for the method, wider issues in the housing market like regulatory delays, development charges and mortgage rules also need to be fixed for modular to really gain traction, he said.

“There are a lot of barriers, there’s a lot of risk, and that’s why we need all of these systemic changes to make sure that the investment pays off.”

The case of Z Modular shows that support is increasing, but still isn’t enough.

Last fall, the company proudly announced it was the first to secure insurance from Canada’s housing agency for a modular apartment build, helping to lower costs.

Some eight months later though, Z Modular said it was closing its housing factory in Kitchener, Ont., at a loss of about 150 jobs, and would be focusing instead on the U.S. market.

The company said the decision was prompted by inefficiencies in financing, rising costs and regulatory delays.

“Despite an obvious housing crisis, Canada has lacked the foresight to enact the changes necessary to encourage investment and enable developers to be successful,” Barry Zekelman, CEO of Z Modular owner Zekelman Industries, said in a June statement.

“Unfortunately, despite our investment of tens of millions of dollars, our teammates have become the victim of the tragic reality of a broken system,” he said.

A big part of the challenge with ramping up modular construction is that it costs a lot to get a factory going, and it needs steady demand to pay for all the fixed costs. That doesn’t fit well with the vagaries of Canada’s housing market, said Lee.

“Because of the boom-bust cycle, it’s really tough to make those investments … if you have that big overhead, instead of just slowing down, it can make you go bankrupt.”

The modular industry is littered with examples of the bust side, ranging from Nomodic Modular Structures Inc. going under last fall with social housing projects half built and a few million dollars in debt, to B.C.-based Nexii Building Solutions, which boasted of a more than $2 billion valuation two years ago before going bankrupt earlier this year.

There are companies managing to make inroads, however.

Bird Construction Inc. bought into a modular business in 2017, and last year it secured a contract to build Canada’s tallest modular project: a 14-storey apartment in Vancouver for B.C.’s housing agency.

“Modular construction is gaining considerable momentum in North America,” Bird chief executive Teri McKibbon said in a statement at the time.

Alberta-based Northgate Industries Ltd., which has been in the modular business for over 50 years, has succeeded in part through diversification, said director Ali Salman.

The company builds everything from remote work camps to rural hospitals and has shipped housing units everywhere from Tuktoyaktuk, N.W.T., to Hawaii and South America.

A push for government-led rapid housing supply has helped create demand closer to home in places like Edmonton, but there’s less traction on the private side, said Salman.

“The private sector is picking it up only if the area has a very high labour cost, or it’s a very remote area.”

There’s also resistance within the housing industry, as everyone from contractors to engineers to architects defend their territory, and keep doing things the way they’ve always done, he said.

But not having a predictable, steady flow of demand is still the biggest barrier, said Salman. He said he would like to see the kind of government support for growth that industries like automotive and oil and gas have received.

Such support has proven to work in places like Scandinavia, he noted, where modular construction makes up almost half of the housing stock.

But given Canada’s largely fragmented construction sector, more awareness is also needed to increase adoption, said Steven Beites, a professor at Laurentian University’s McEwen School of Architecture.

He said that while most homes won’t be rolling out of factories any time soon, there’s plenty of room to increase the use of prefabricated parts like wall panels.

“It’s really about educating and sharing that knowledge, and allowing local builders to continue to do their traditional way but also start to engage in more prefab in hopes that they’ll see the benefits.”

Advances in building techniques would open up the potential for more sustainable building materials, and moving away from “really antiquated methods of building,” said Beites.

“We’ve been building stick-frame homes for 150-plus years … it’s critical for us here in Canada to start embracing prefab and modular as a way to gain those efficiencies.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Aug. 4, 2024.