Science

Hubble spots double quasars in merging galaxies – Phys.org

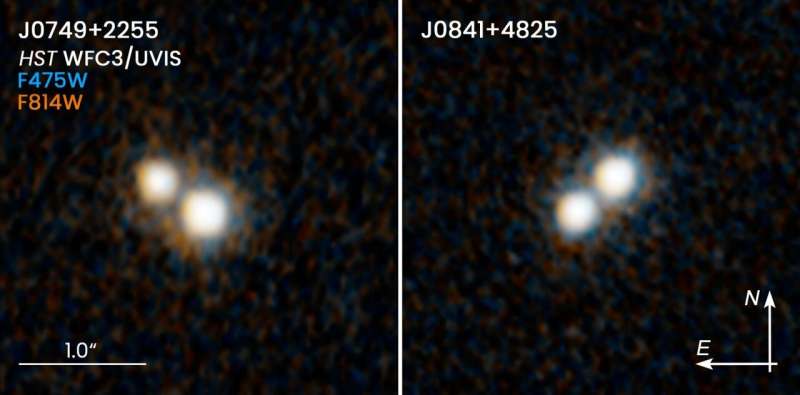

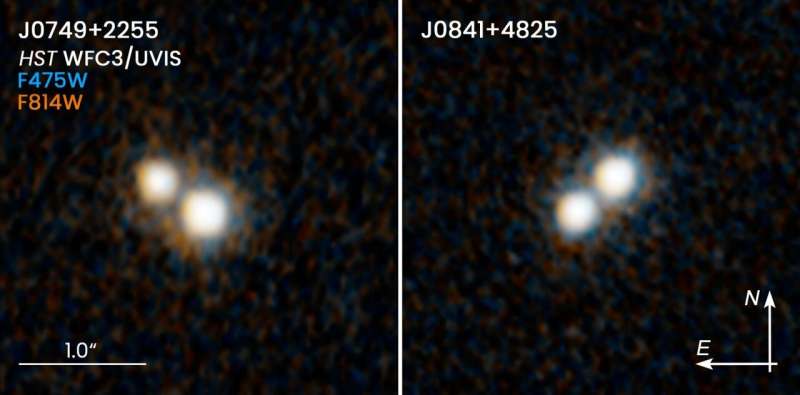

NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope is “seeing double.” Peering back 10 billion years into the universe’s past, Hubble astronomers found a pair of quasars that are so close to each other they look like a single object in ground-based telescopic photos, but not in Hubble’s crisp view.

The researchers believe the quasars are very close to each other because they reside in the cores of two merging galaxies. The team went on to win the “daily double” by finding yet another quasar pair in another colliding galaxy duo.

A quasar is a brilliant beacon of intense light from the center of a distant galaxy that can outshine the entire galaxy. It is powered by a supermassive black hole voraciously feeding on inflating matter, unleashing a torrent of radiation.

“We estimate that in the distant universe, for every 1,000 quasars, there is one double quasar. So finding these double quasars is like finding a needle in a haystack,” said lead researcher Yue Shen of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

The discovery of these four quasars offers a new way to probe collisions among galaxies and the merging of supermassive black holes in the early universe, researchers say.

Quasars are scattered all across the sky and were most abundant 10 billion years ago. There were a lot of galaxy mergers back then feeding the black holes. Therefore, astronomers theorize there should have been many dual quasars during that time.

“This truly is the first sample of dual quasars at the peak epoch of galaxy formation with which we can use to probe ideas about how supermassive black holes come together to eventually form a binary,” said research team member Nadia Zakamska of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

The team’s results appeared in the April 1 online issue of the journal Nature Astronomy.

Shen and Zakamska are members of a team that is using Hubble, the European Space Agency’s Gaia space observatory, and the Sloan Digital Sky Survey, as well as several ground-based telescopes, to compile a robust census of quasar pairs in the early universe.

The observations are important because a quasar’s role in galactic encounters plays a critical part in galaxy formation, the researchers say. As two close galaxies begin to distort each other gravitationally, their interaction funnels material into their respective black holes, igniting their quasars.

Over time, radiation from these high-intensity “light bulbs” launch powerful galactic winds, which sweep out most of the gas from the merging galaxies. Deprived of gas, star formation ceases, and the galaxies evolve into elliptical galaxies.

“Quasars make a profound impact on galaxy formation in the universe,” Zakamska said. “Finding dual quasars at this early epoch is important because we can now test our long-standing ideas of how black holes and their host galaxies evolve together.”

Astronomers have discovered more than 100 double quasars in merging galaxies so far. However, none of them is as old as the two double quasars in this study.

The Hubble images show that quasars within each pair are only about 10,000 light-years apart. By comparison, our Sun is 26,000 light-years from the supermassive black hole in the center of our galaxy.

The pairs of host galaxies will eventually merge, and then the quasars also will coalesce, resulting in an even more massive, single solitary black hole.

Finding them wasn’t easy. Hubble is the only telescope with vision sharp enough to peer back to the early universe and distinguish two close quasars that are so far away from Earth. However, Hubble’s sharp resolution alone isn’t good enough to find these dual light beacons.

Astronomers first needed to figure out where to point Hubble to study them. The challenge is that the sky is blanketed with a tapestry of ancient quasars that flared to life 10 billion years ago, only a tiny fraction of which are dual. It took an imaginative and innovative technique that required the help of the European Space Agency’s Gaia satellite and the ground-based Sloan Digital Sky Survey to compile a group of potential candidates for Hubble to observe.

Located at Apache Point Observatory in New Mexico, the Sloan telescope produces three-dimensional maps of objects throughout the sky. The team pored through the Sloan survey to identify the quasars to study more closely.

[embedded content]

The researchers then enlisted the Gaia observatory to help pinpoint potential double-quasar candidates. Gaia measures the positions, distances, and motions of nearby celestial objects very precisely. But the team devised a new, innovative application for Gaia that could be used for exploring the distant universe. They used the observatory’s database to search for quasars that mimic the apparent motion of nearby stars. The quasars appear as single objects in the Gaia data. However, Gaia can pick up a subtle, unexpected “jiggle” in the apparent position of some of the quasars it observes.

The quasars aren’t moving through space in any measurable way, but instead their jiggle could be evidence of random fluctuations of light as each member of the quasar pair varies in brightness. Quasars flicker in brightness on timescales of days to months, depending on their black hole’s feeding schedule.

This alternating brightness between the quasar pair is similar to seeing a railroad crossing signal from a distance. As the lights on both sides of the stationary signal alternately flash, the sign gives the illusion of “jiggling.”

When the first four targets were observed with Hubble, its crisp vision revealed that two of the targets are two close pairs of quasars. The researchers said it was a “light bulb moment” that verified their plan of using Sloan, Gaia, and Hubble to hunt for the ancient, elusive double powerhouses.

Team member Xin Liu of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign called the Hubble confirmation a “happy surprise.” She has long hunted for double quasars closer to Earth using different techniques with ground-based telescopes. “The new technique can not only discover dual quasars much further away, but it is much more efficient than the methods we’ve used before,” she said.

Their Nature Astronomy article is a “proof of concept that really demonstrates that our targeted search for dual quasars is very efficient,” said team member Hsiang-Chih Hwang, a graduate student at Johns Hopkins University and the principal investigator of the Hubble program. “It opens a new direction where we can accumulate a lot more interesting systems to follow up, which astronomers weren’t able to do with previous techniques or datasets.”

The team also obtained follow-up observations with the National Science Foundation NOIRLab’s Gemini telescopes. “Gemini’s spatially-resolved spectroscopy can unambiguously reject interlopers due to chance superpositions from unassociated star-quasar systems, where the foreground star is coincidentally aligned with the background quasar,” said team member Yu-Ching Chen, a graduate student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Although the team is convinced of their result, they say there is a slight chance that the Hubble snapshots captured double images of the same quasar, an illusion caused by gravitational lensing. This phenomenon occurs when the gravity of a massive foreground galaxy splits and amplifies the light from the background quasar into two mirror images. However, the researchers think this scenario is highly unlikely because Hubble did not detect any foreground galaxies near the two quasar pairs.

Galactic mergers were more plentiful billions of years ago, but a few are still happening today. One example is NGC 6240, a nearby system of merging galaxies that has two and possibly even three supermassive black holes. An even closer galactic merger will occur in a few billion years when our Milky Way galaxy collides with neighboring Andromeda galaxy. The galactic tussle would likely feed the supermassive black holes in the core of each galaxy, igniting them as quasars.

Future telescopes may offer more insight into these merging systems. NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope, an infrared observatory scheduled to launch later this year, will probe the quasars’ host galaxies. Webb will show the signatures of galactic mergers, such as the distribution of starlight and the long streamers of gas pulled from the interacting galaxies.

Yue Shen et al. A hidden population of high-redshift double quasars unveiled by astrometry, Nature Astronomy (2021). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-021-01323-1

Citation:

Hubble spots double quasars in merging galaxies (2021, April 6)

retrieved 6 April 2021

from https://phys.org/news/2021-04-hubble-quasars-merging-galaxies.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Science

Voyager 1 transmitting data again after Nasa remotely fixes 46-year-old probe – The Guardian

Earth’s most distant spacecraft, Voyager 1, has started communicating properly again with Nasa after engineers worked for months to remotely fix the 46-year-old probe.

Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), which makes and operates the agency’s robotic spacecraft, said in December that the probe – more than 15bn miles (24bn kilometres) away – was sending gibberish code back to Earth.

In an update released on Monday, JPL announced the mission team had managed “after some inventive sleuthing” to receive usable data about the health and status of Voyager 1’s engineering systems. “The next step is to enable the spacecraft to begin returning science data again,” JPL said. Despite the fault, Voyager 1 had operated normally throughout, it added.

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 was designed with the primary goal of conducting close-up studies of Jupiter and Saturn in a five-year mission. However, its journey continued and the spacecraft is now approaching a half-century in operation.

Voyager 1 crossed into interstellar space in August 2012, making it the first human-made object to venture out of the solar system. It is currently travelling at 37,800mph (60,821km/h).

The recent problem was related to one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers, which are responsible for packaging the science and engineering data before it is sent to Earth. Unable to repair a broken chip, the JPL team decided to move the corrupted code elsewhere, a tricky job considering the old technology.

The computers on Voyager 1 and its sister probe, Voyager 2, have less than 70 kilobytes of memory in total – the equivalent of a low-resolution computer image. They use old-fashioned digital tape to record data.

The fix was transmitted from Earth on 18 April but it took two days to assess if it had been successful as a radio signal takes about 22 and a half hours to reach Voyager 1 and another 22 and a half hours for a response to come back to Earth. “When the mission flight team heard back from the spacecraft on 20 April, they saw that the modification worked,” JPL said.

Alongside its announcement, JPL posted a photo of members of the Voyager flight team cheering and clapping in a conference room after receiving usable data again, with laptops, notebooks and doughnuts on the table in front of them.

The Retired Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who flew two space shuttle missions and acted as commander of the International Space Station, compared the JPL mission to long-distance maintenance on a vintage car.

“Imagine a computer chip fails in your 1977 vehicle. Now imagine it’s in interstellar space, 15bn miles away,” Hadfield wrote on X. “Nasa’s Voyager probe just got fixed by this team of brilliant software mechanics.

Voyager 1 and 2 have made numerous scientific discoveries, including taking detailed recordings of Saturn and revealing that Jupiter also has rings, as well as active volcanism on one of its moons, Io. The probes later discovered 23 new moons around the outer planets.

As their trajectory takes them so far from the sun, the Voyager probes are unable to use solar panels, instead converting the heat produced from the natural radioactive decay of plutonium into electricity to power the spacecraft’s systems.

Nasa hopes to continue to collect data from the two Voyager spacecraft for several more years but engineers expect the probes will be too far out of range to communicate in about a decade, depending on how much power they can generate. Voyager 2 is slightly behind its twin and is moving slightly slower.

In roughly 40,000 years, the probes will pass relatively close, in astronomical terms, to two stars. Voyager 1 will come within 1.7 light years of a star in the constellation Ursa Minor, while Voyager 2 will come within a similar distance of a star called Ross 248 in the constellation of Andromeda.

Science

iN PHOTOS: Nature lovers celebrate flora, fauna for Earth Day in Kamloops, Okanagan | iNFOnews | Thompson-Okanagan's News Source – iNFOnews

Photographers are sharing their favourite photos of flora and fauna captured in Kamloops and the Okanagan in celebration of Earth Day.

First started in the United States in the 70s, the special day on April 22 continues to be acknowledged around the globe. It’s a day to celebrate the planet and a reminder of the need for environmental conservation and sustainability, according to EarthDay.org.

These stunning nature photos show life in ponds and forests, in skies and on mountains, capturing the beauty and wonder of our local natural environments.

Area photographers shared some of their favourite finds and artistic captures. From frogs to flowers, the great outdoors is teeming with life.

If you have nature photos you want to share, send them to news@infonews.ca.

To contact a reporter for this story, email Shannon Ainslie or call 250-819-6089 or email the editor. You can also submit photos, videos or news tips to the newsroom and be entered to win a monthly prize draw.

We welcome your comments and opinions on our stories but play nice. We won’t censor or delete comments unless they contain off-topic statements or links, unnecessary vulgarity, false facts, spam or obviously fake profiles. If you have any concerns about what you see in comments, email the editor in the link above. SUBSCRIBE to our awesome newsletter here.

Science

An extra moon may be orbiting Earth — and scientists think they know exactly where it came from – Livescience.com

A fast-spinning asteroid that orbits in time with Earth may be a wayward chunk of the moon. Now, scientists think they know exactly which lunar crater it came from.

A new study, published April 19 in the journal Nature Astronomy, finds that the near-Earth asteroid 469219 Kamo’oalewa may have been flung into space when a mile-wide (1.6 kilometers) space rock hit the moon, creating the Giordano Bruno crater.

Kamo’oalewa’s light reflectance matches that of weathered lunar rock, and its size, age and spin all match up with the 13.6-mile-wide (22 km) crater, which sits on the far side of the moon, the study researchers reported.

China plans to launch a sample-return mission to the asteroid in 2025. Called Tianwen-2, the mission will return pieces of Kamo’oalewa about 2.5 years later, according to Live Science’s sister site Space.com.

“The possibility of a lunar-derived origin adds unexpected intrigue to the [Tianwen-2] mission and presents additional technical challenges for the sample return,” Bin Cheng, a planetary scientist at Tsinghua University and a co-author of the new study, told Science.

Related: How many moons does Earth have?

Kamo’oalewa was discovered in 2016 by researchers at Haleakala Observatory in Hawaii. It has a diameter of about 100 to 200 feet (approximately 30 to 60 meters, or about the size of a large Ferris wheel) and spins at a rapid clip of one rotation every 28 minutes. The asteroid orbits the sun in a similar path to Earth, sometimes approaching within 10 million miles (16 million km).

window.sliceComponents = window.sliceComponents || ;

externalsScriptLoaded.then(() => {

window.reliablePageLoad.then(() => {

var componentContainer = document.querySelector(“#slice-container-newsletterForm-articleInbodyContent-UG4KJ7zrhxAytcHZQxVzXK”);

if (componentContainer)

var data = “layout”:”inbodyContent”,”header”:”Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now”,”tagline”:”Get the worldu2019s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.”,”formFooterText”:”By submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.”,”successMessage”:”body”:”Thank you for signing up. You will receive a confirmation email shortly.”,”failureMessage”:”There was a problem. Please refresh the page and try again.”,”method”:”POST”,”inputs”:[“type”:”hidden”,”name”:”NAME”,”type”:”email”,”name”:”MAIL”,”placeholder”:”Your Email Address”,”required”:true,”type”:”hidden”,”name”:”NEWSLETTER_CODE”,”value”:”XLS-D”,”type”:”hidden”,”name”:”LANG”,”value”:”EN”,”type”:”hidden”,”name”:”SOURCE”,”value”:”60″,”type”:”hidden”,”name”:”COUNTRY”,”type”:”checkbox”,”name”:”CONTACT_OTHER_BRANDS”,”label”:”text”:”Contact me with news and offers from other Future brands”,”type”:”checkbox”,”name”:”CONTACT_PARTNERS”,”label”:”text”:”Receive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsors”,”type”:”submit”,”value”:”Sign me up”,”required”:true],”endpoint”:”https://newsletter-subscribe.futureplc.com/v2/submission/submit”,”analytics”:[“analyticsType”:”widgetViewed”],”ariaLabels”:;

var triggerHydrate = function()

window.sliceComponents.newsletterForm.hydrate(data, componentContainer);

if (window.lazyObserveElement)

window.lazyObserveElement(componentContainer, triggerHydrate);

else

triggerHydrate();

}).catch(err => console.log(‘Hydration Script has failed for newsletterForm-articleInbodyContent-UG4KJ7zrhxAytcHZQxVzXK Slice’, err));

}).catch(err => console.log(‘Externals script failed to load’, err));

Follow-up studies suggested that the light spectra reflected by Kamo’oalewa was very similar to the spectra reflected by samples brought back to Earth by lunar missions, as well as to meteorites known to come from the moon.

Cheng and his colleagues first calculated what size object and what speed of impact would be necessary to eject a fragment like Kamo’oalewa from the lunar surface, as well as what size crater would be left behind. They figured out that the asteroid could have resulted from a 45-degree impact at about 420,000 mph (18 kilometers per second) and would have left a 6-to-12-mile-wide (10 to 20 km) crater.

There are tens of thousands of craters that size on the moon, but most are ancient, the researchers wrote in their paper. Near-Earth asteroids usually last only about 10 million years, or at most up to 100 million years before they crash into the sun or a planet or get flung out of the solar system entirely. By looking at young craters, the team narrowed down the contenders to a few dozen options.

The researchers focused on Giordano Bruno, which matched the requirements for both size and age. They found that the impact that formed Giordano Bruno could have created as many as three still-extant Kamo’oalewa-like objects. This makes Giordano Bruno crater the most likely source of the asteroid, the researchers concluded.

“It’s like finding out which tree a fallen leaf on the ground came from in a vast forest,” Cheng wrote on X, formerly known as Twitter.

Confirmation will come after the Tianwen-2 mission brings a piece of Kamo’oalewa back to Earth. Scientists already have a sample of what is believed to be ejecta from Giordano Bruno crater in the Luna 24 sample, a bit of moon rock brought back to Earth in a 1976 NASA mission. By comparing the two, researchers could verify Kamo’oalewa’s origin.

Editor’s note: This article’s headline was updated on April 23 at 10 a.m. ET.

-

Health23 hours ago

Health23 hours agoSee how chicken farmers are trying to stop the spread of bird flu – Fox 46 Charlotte

-

Science21 hours ago

Science21 hours agoOsoyoos commuters invited to celebrate Earth Day with the Leg Day challenge – Oliver/Osoyoos News – Castanet.net

-

Politics21 hours ago

Politics21 hours agoHaberman on why David Pecker testifying is ‘fundamentally different’ – CNN

-

News21 hours ago

Freeland defends budget measures, as premiers push back on federal involvement – CBC News

-

Economy21 hours ago

The Fed's Forecasting Method Looks Increasingly Outdated as Bernanke Pitches an Alternative – Bloomberg

-

Business20 hours ago

Gildan replacing five directors ahead of AGM, will back two Browning West nominees – Yahoo Canada Finance

-

Health20 hours ago

Health20 hours agoIt's possible to rely on plant proteins without sacrificing training gains, new studies say – The Globe and Mail

-

Tech20 hours ago

Tech20 hours agoMeta Expands VR Operating System to Third-Party Hardware Makers – MacRumors