Politics

Identity politics isn’t hurting liberalism. It’s saving it. – Vox.com

American liberalism is in desperate need of renewal. Its ideas too often feel stale, its nostrums unsuited to beating back the authoritarian populist tide.

Yet there is an opportunity for revival — if liberals are willing to more forthrightly embrace the politics of identity.

To many liberals, such a suggestion will sound like blasphemy. Since mere days after Donald Trump’s 2016 victory, an unending stream of op-eds and books have accused “identity politics” — defined loosely as a left-wing political style that centers the interests and concerns of oppressed groups — of driving the country off a moral and political cliff.

These critics accuse identity politics of being a cancer on the very idea of liberalism, pulling the mainstream American left away from a politics of equal citizenship and shared civic responsibility. It is, moreover, political suicide, a woke purism that makes it impossible to form winning political coalitions — evidenced, in critics’ minds, by the backlash to Bernie Sanders’s embrace of the popular podcast host Joe Rogan.

The idea that identity politics is at odds with liberalism has become conventional wisdom in parts of the American political and intellectual elite. Harvard psychologist Steven Pinker has condemned contemporary identity politics as “an enemy of reason and Enlightenment values.” New York Times columnist Bari Weiss argues that the “corrupt identity politics of the left” amounts to a dangerously intolerant worldview. And New York magazine’s Andrew Sullivan claims the “woke left” seems “not to genuinely believe in liberalism, liberal democracy, or persuasion.” This line of thinking is practically the founding credo of the school of internet thought known as the Intellectual Dark Web.

It is also deeply, profoundly wrong.

What these critics lambaste as an attack on liberalism is actually its best form: the logical extension of liberalism’s core commitment to social equality and democracy, adapted to address modern sources of inequality. A liberalism that rejects identity politics is a liberalism for the powerful, one that relegates the interests of marginalized groups to second-class status.

But identity politics is not only important as a matter of liberal principle. In the face of an existential threat from right-wing populists in Europe and the United States, liberals need to harness new sources of political energy to fight back. This is not a matter of short-term politics, of whether being “too woke” will help or hurt Democrats in 2020, but a deeper and more fundamental question: what types of organizations and activist movements are required to make liberalism sustainable in the 21st century. And there is good reason to believe the passions stirred by identity politics can renew a liberalism gone haggard.

To say that liberalism and identity politics are at odds is to misunderstand our political situation. Identity politics isn’t merely compatible with liberalism; it is, in fact, liberalism’s truest face. If liberalism wishes to succeed in 21st-century America, it shouldn’t reject identity politics — it should embrace it.

All politics is, in a certain sense, identity politics. Every kind of political approach appeals to particular aspects of voters’ identities; some are just more explicit than others.

But critics of identity politics have a very particular politics in mind — a mode of rhetoric and organizing that prioritizes the concerns and experiences of historically marginalized groups, emphasizing the group’s particularity.

To understand why this kind of identity politics is so controversial — and what its critics often get wrong about it — we need to turn to the work of the late University of Chicago philosopher Iris Marion Young.

In 1990, Young published a classic book titled Justice and the Politics of Difference. At the time, political philosophy was dominated by internal debates among liberals who focused heavily on the question of wealth distribution. Young, both a philosopher and a left activist, found this narrow discourse unsatisfying.

In her view, mainstream American liberalism had assumed a particular account of what social equality means: “that equal social status for all persons requires treating everyone according to the same principles, rules, and standards.” Securing “equality” on this view means things like desegregation and passing nondiscrimination laws, efforts to end overt discrimination against marginalized groups.

This is an important start, Young argues, but not nearly enough. The push for formally equal treatment can’t eliminate all sources of structural inequality; in fact, it can serve to mask and even deepen them. Judging a poor black kid and a rich white one by the same allegedly meritocratic college admissions standards, for example, will likely lead to the rich white one’s admission — perpetuating a punishing form of inequality that started at birth.

Young sees an antidote in a political vision she developed out of experiences in social movements, which she calls “the politics of difference.” Sometimes, Young argues, achieving true equality demands treating groups differently rather than the same. “The specificity of each group requires a specific set of rights for each, and for some a more comprehensive system than for others,” Young writes. The goal is identity consciousness rather than identity blindness: “Black Lives Matter” over “All Lives Matter.”

She did not like using the term “identity politics” for this approach, arguing in her 2000 book Inclusion and Democracy that it was misleadingly narrow. But two decades later, what she sketched out is what we understand “identity politics” to mean.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19725927/GettyImages_472082216_bw.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19725927/GettyImages_472082216_bw.jpg)

Young’s philosophical precision allows us to understand what’s distinctive about contemporary identity politics. It also helps us understand why critics see it as such a threat.

Identity politics’ dissatisfaction with formal equal treatment is, in their view, fundamentally illiberal. Its emphasis on correcting structural discrimination can morph into a kind of authoritarianism, an obsession with the policing of speech and behaviors (especially from white, straight, cisgender men) at odds with liberalism’s core commitments to individual rights, so the critics fret. They see college students disinviting conservative speakers for being “problematic,” or “canceling” celebrities who violate the rules of acceptable discourse on race or gender identity, as evidence that identity politics’ fundamental aim is overturning liberalism in the name of equality.

This approach is not only illiberal, the critics argue, but self-defeating. The more emphasis that is placed on the separateness of American social groups, the less space there is for a politically effective and wide-ranging liberalism.

“The only way to [win power] is to have a message that appeals to as many people as possible and pulls them together,” Columbia professor Mark Lilla writes in his recent book The Once and Future Liberal. “Identity liberalism does just the opposite.”

Many of these critics see themselves as coming from a relatively progressive and firmly liberal starting point. They tend to profess support for the ideals of racial or gender equality. What they can’t abide is a political approach that emphasizes difference, shaping its policy proposals around specific oppressions rather than universal ideals.

It is a philosophical argument with political implications: a claim that the essence of identity politics is illiberal, and for that reason its continued influence on the American left augurs both moral and electoral doom.

It’s hardly absurd for someone like Lilla to see tension between liberalism and identity politics. Young herself described the politics of difference as not a species of liberalism but a challenge to it.

But her stance notwithstanding, political philosophers have come to see the politics of identity as part of a vibrant liberalism. In 1998, Canadian scholar Will Kymlicka identified an “emerging consensus” among political philosophers on what he calls “liberal multiculturalism,” the idea that “groups have a valid claim, not only to tolerance and non-discrimination, but also to explicit accommodation, recognition and representation within the institutions of the larger society.”

If we examine liberalism’s core moral commitments, Kymlicka’s consensus shouldn’t be a surprise.

The quintessential liberal value is freedom. Liberalism’s core political ambition is to create a society where citizens are free to participate as equals, cooperating on mutually agreeable terms in political life and pursuing whatever vision of private life they find meaningful and fulfilling. Freedom in this sense cannot be achieved in political systems defined by identity-based oppression. When members of some social groups face barriers to living the life they choose, purely as a result of their membership in that group, then the society they live in is failing on liberal terms.

Identity politics seeks to draw attention to and combat such sources of unfreedom. Consider the following facts about American life:

- The median black family’s wealth is one-tenth that of the median white family.

- The average American woman spends over 11 more hours per week doing unpaid home labor than the average man.

- LGBTQ youth are about five times more likely to attempt suicide than (respectively) straight and cisgender peers.

There is no law saying black people can’t own houses, that women married to men must do the cooking and cleaning, or that LGBTQ teens must harm themselves. These problems have more subtle causes, including legacies of historical discrimination, deeply embedded social norms, and inadequate legislative attention to the particular circumstances of marginalized groups.

Identity politics’ focus on the need to go beyond anti-discrimination works to open new avenues for dealing with the insidious nature of modern group-based inequality. Once you understand that this is the actual aim of identity politics, it becomes clear that critiques of its alleged authoritarianism miss the forest for the trees.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19725945/GettyImages_1194542381_bw.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19725945/GettyImages_1194542381_bw.jpg)

It is of course true that one can point to illiberal behavior by activists in the name of identity politics: Think of the student group at the City University of New York that attempted to shout down a relatively mainstream conservative legal scholar’s lecture out of hostility to his views on immigration law. But instances of campus intolerance are actually quite uncommon, despite their omnipresence in the media, and the idea that a handful of student excesses represent the core of “identity politics” is a mistake.

One can say the same thing for social media outrages. It’s certainly true that many practitioners of identity politics send over-the-top tweets or pen Facebook posts calling for people to be fired without good cause. It’s also true that some practitioners of every kind of politics do these things. Holding up an outrageous-sounding tweet as representative of the allegedly authoritarian heart of identity politics is a basic analytical error: confusing a platform problem, the way social media highlights the most extreme versions of all ideologies, with a doctrinal defect in identity politics.

Merely because a liberal movement contains some illiberal components doesn’t make it fundamentally illiberal; if it did, then slave-owning American founders and bigoted Enlightenment philosophers would have to be booted out of the liberal canon.

The key question is whether the agenda and aims of identity politics’ adherents advance liberal freedom compared to the status quo. On this point, it’s clear that the practitioners of “identity politics” are on the liberal side.

In recent years, we have seen champions of identity politics rack up impressive accomplishments — victories like defeating prosecutors with troubling records on race at the ballot box, getting sexual assault allegations taken seriously in the workplace, and securing health care coverage for transition-related medical care.

These are hardly examples of woke Stalinism. They are instead victories of liberal reform and democratic activism, incremental changes aimed at addressing deep-rooted sources of unfreedom.

Time and again throughout American history, from abolitionism to the movement for same-sex marriage, members of marginalized groups have refused to abandon liberalism’s promises. They put their lives on the line, risking death on Civil War battlefields and in the streets of Birmingham, in defense of liberal ideals. When they demanded change, they won it through the push-and-pull of democratic politics and political activism that constitute the heart of liberal praxis. In essayist Adam Serwer’s evocative phrasing: “The American creed has no more devoted adherents than those who have been historically denied its promises.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19725906/identity_politics_liberalism_board_2.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19725906/identity_politics_liberalism_board_2.jpg)

Christina Animashaun/Vox

Today’s practitioners of identity politics are the proper heirs to this tradition. Former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams, one of the most prominent defenders of “identity politics” in American public life, has devoted her post-election career to an unimpeachably liberal cause — fighting restrictions on the franchise, particularly those that disproportionately affect black voters.

In a recent Foreign Affairs essay, Abrams made the case that one of the central aims of identity politics is bolstering liberalism — that it is “activism that will strengthen democratic rule, not threaten it.” In Abrams’s view, the persistence of structural oppression, and in particular the Trump-era backlash to social progress, requires careful attention to identity, and in particular what marginalized groups want from their political elites.

“By embracing identity and its prickly, uncomfortable contours,” Abrams wrote, “Americans will become more likely to grow as one.”

The critics of identity politics have another complaint: that its hold on the Democratic Party can only lead to electoral perdition. Abrams, as inspirational as many find her, did lose the 2018 Georgia gubernatorial race. Maybe identity politics can be defended theoretically but in practice alienates too many people to be put in practice.

It’s possible to challenge the specifics of these arguments. Abrams didn’t win, but it was a very tight loss in a historically red state (in fact, 2018 was the closest Georgia gubernatorial election in the state in more than 50 years). And you can point to many examples that go in the other direction — at the local, state, and national levels.

But it would be myopic to tie ourselves up in these near-term (and frankly inconclusive) tactical arguments. We have a broader crisis to worry about.

Debating the interests of the Democratic Party confines the imagination; rising illiberalism in the United States is a deeper problem than the Trump presidency. To reckon with it, we need to take a longer view, looking at the beliefs and sources of activist energy that define the contours of what’s possible in American electoral politics.

Since World War II, liberalism and its core beliefs about rights and freedom have served as something like the operating system for democratic politics. But in recent years, this consensus has come under severe stress. Elite failures and global catastrophes — particularly the one-two punch of the financial and refugee crises — have caused Western publics to lose faith in the liberal order’s guardians. Illiberal right-wing populism has emerged as a potent alternative model. The West’s fundamental commitment to liberalism is coming into question.

Liberals are in the midst of war — and in it, giving up identity politics amounts to a kind of unilateral disarmament. Today’s political contests, in both the United States and Europe, are increasingly defined by conflict surrounding demographic change and the erosion of traditional social hierarchies. These are the central issues in our politics, the ones that most powerfully motivate people to vote and join political organizations.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19725963/GettyImages_1140886803_bw.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19725963/GettyImages_1140886803_bw.jpg)

The anti-liberal side has pegged its vision almost entirely to backlash politics, to rolling back the gains made by ethnic and racial minorities, women, and the LGBTQ community. The challenge for liberals is not primarily winning over voters who find that regressive vision appealing; no modern liberal party can be as authentically bigoted as a far-right one. At the same time, liberals should not write off entire heterogeneous demographic blocs like “the white working class” as unpersuadable. Instead, the main task of liberal politics should be mobilizing those from all backgrounds who oppose the far-right’s vision — knitting together in common cause a staggeringly diverse array of people with very different experiences.

The 2017 Women’s March is a concrete example of how identity politics can help in this struggle.

The march was billed, at the time, as both an expression of feminist rage and the major anti-Trump action the weekend of the inauguration. Some liberal identity skeptics fretted that these goals were antithetical; that the particularism of the event’s feminist rhetoric would end up dividing the anti-Trump coalition.

“I think many men assume the ‘Women’s March’ is supposed to be women-only, which is why it was a bad name for the main anti-Trump march,” New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait wrote. “There are many grounds on which to object to Trump. Feminism is one. I think [the] goal should be to get all of them together.”

Chait’s concerns were clearly unfounded. The 2017 Women’s March was by some estimates the largest single day of protest in US history, with somewhere in the range of 3 million to 5 million people attending the various marches nationwide. Feminism, far from being a divisive theme, served to mobilize large numbers of people to get out and demonstrate against America’s illiberal turn.

But what happened next is particularly interesting: The experience of attending Women’s Marches seems to have galvanized a significant number of people — overwhelmingly women — to engage in sustained activism for both gender equality and the defense of liberalism more broadly.

In the years following the 2017 demonstrations, Harvard researchers Leah Gose and Theda Skocpol conducted extensive fieldwork among anti-Trump activists. They found that the march helped mobilize many new activists — the bulk of whom were middle-class, educated white women in their 50s or older. “Following the marches,” they found, “clusters of women in thousands of communities across America carried on with forming local groups to sustain anti-Trump activism.”

The Women’s March seems to have played a crucial role in turning these women into activists who not only opposed Trump but aimed to defend liberalism’s promise of equal freedom. Activists interviewed by Gose and Skocpol frequently cited a concern for the health of American democracy as a reason for their engagement. Despite being heavily white, they also worked on issues that are of particular concern to racial minorities — organizing against (for example) the white nationalist rally in Charlottesville and child separation.

“As before throughout American history,” Gose and Skocpol write, “women’s civic activism may revitalize democratic engagement and promote a new birth of responsive government in communities across the land.”

In a recent working paper, political scientist Jonathan Pinckney took a close look at the impact of the Women’s March on three metrics: increase of size in Democratic-aligned activist groups, ideology of Democratic members of Congress, and the share of the Democratic vote in 2018. He found that areas with larger attendance at the 2017 marches later saw “significantly increased movement activity, left-ward shifts in congressional voting scores, and a greater swing to the Democrats in the 2018 midterm elections.”

The Women’s March itself seems to have largely petered out, succumbing to fatigue and leadership infighting. But its true legacy will be the activist networks it helped create, ones that contributed to sustained and impactful challenges to an illiberal presidency.

This kind of thing is what, in the long run, liberalism needs: a way to make its defense fresh and exciting, mobilizing specific groups toward the collective task of defeating the far right. Doing so will require meeting people where they are, engaging them on the identity issues that matter deeply and profoundly. Knitting this latent energy into a durable and electorally viable coalition will be the work of a generation, but it’s hard to see how American liberalism can get off its heels without trying.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19725991/GettyImages_1098389432_bw.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19725991/GettyImages_1098389432_bw.jpg)

It’s true, of course, that the interests of members of marginalized groups are not always aligned, and that such groups also contain a lot of internal disagreements and diversity. There are always hard questions regarding building coalitions. Should Sanders have denounced Joe Rogan’s endorsement? Is Pete Buttigieg’s dubious record on race and policing disqualifying? These are important questions, and there will be more like them. They will lead to more fights among liberals and the broader left.

But political factions of all ideologies have to make tough judgment calls when it comes time to engage in electoral politics, and there’s nothing about identity politics that makes it uniquely poorly suited to the task.

While the politics of difference is attuned to the specific experiences of social groups, it also contains a universalizing impulse: a sense that all structural injustices — stemming from racism, sexism, class structure, or whatever — are to be opposed. There’s a core commitment to solidarity, to not only listening to the members of other groups but seeing their struggle as linked to your own.

“Having to be accountable to people from diverse social positions with different needs, interests, and experience helps transform discourse from self-regard to appeals to justice,” Young writes in Inclusion and Democracy.

An anti-oppression framework gives people a moral language for articulating their disagreements and perspectives, for constructing a sense of unity and shared purpose out of difference. That we’re having these conversations at all, and are agonizing over what exactly our liberalism should look like, is all to the good — because rebuilding liberalism around anti-oppression values, no matter how difficult it might seem in the moment, is its best hope for an enduring revival.

If all of this is right, and liberalism needs identity politics not just to survive but to succeed, then an obvious question looms: How can it be adapted to take issues of identity more seriously? What might the ideals and aspirations of an identity-focused liberalism be, and how might it imagine making them possible?

One good place to start is the work of CUNY philosopher Charles Mills. Mills’s most famous book, The Racial Contract (1997), is a fundamental critique of the Enlightenment political tradition, arguing that racist attitudes expressed by philosophical giants like Immanuel Kant are not some alien parasite on their theories, but vital to their intellectual enterprises.

It’s the kind of thoroughgoing dissection you might expect from a socialist or black nationalist, someone willing to scrap liberalism altogether. Yet at the end of his most recent book, Black Rights/White Wrongs, Mills explains that his project is not aimed at supplanting liberalism but rather rescuing it — by developing what he calls “black radical liberalism.”

Central to black radical liberalism is the idea of “corrective justice”: the notion that liberalism as it has been practiced historically has fallen badly short of its highest ideals of guaranteeing equal freedom, and that the task of modern liberalism ought to be rectifying the racial inequalities of its past incarnations.

Mills’s approach is refreshing because it moves beyond the strange conservatism in so much liberal writing today. His work is not an uncritical valorization of the Enlightenment nor a paean to dead white thinkers; it does not aim to Make Liberalism Great Again. It is instead a harshly critical account of liberalism’s history that nonetheless aims to advance liberalism’s core values and secure its greatest accomplishments.

The animating force of identity politics, what gives it such extraordinary power to mobilize, is deep wells of outrage at structural injustice. Millions of people see the cruelties of the Trump administration — its detention of migrant children in camps, the Muslim ban, the plan to define transgender people out of existence by executive fiat, the president’s description of Charlottesville neo-Nazis as “very fine people”— and want to do something.

Today’s liberals often focus their arguments on bloodless abstractions like “democratic norms” and the “liberal international order.” I don’t deny that these things are important; I’ve written in their defense myself.

But people aren’t angry about norm erosion in the way they are about, say, state-sanctioned mistreatment of migrant kids. By making identity politics something not outside of liberalism but at the center of it, liberals can enlist the energies of identity to the defense of liberalism itself.

Doing that successfully requires a level of Millsian radicalism. While this sort of identity liberalism would not reject the accomplishments of the past, it requires admitting their insufficiency. It means accepting that liberalism is a doctrine that has failed in key ways, and that repairing its errors requires centering the interests of the groups that have been most wronged. It means appealing to the specificity of group experiences, while also emphasizing their shared interests in the twinned fights against oppression and for liberal democracy.

This approach will require compromises from some mainstream liberals, who will need to start welcoming in people and ideas they might not like. They’ll need to get over squeamishness about student activists and their pain regarding political correctness, to recognize that their vision of balancing competing political interests won’t always win out. That’s not to say they can’t argue for their ideas; this type of liberal can and should be entitled to make the case for more cautious political approaches. But liberals need to stop trying to play gatekeeper, to banish ideas like intersectionality to the illiberal wilds.

Because the practitioners of identity politics are not illiberal. They are, in fact, some of the best friends liberalism has today. The sooner liberals acknowledge that, the closer we will be to a liberal revival.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19726006/GettyImages_907708340_bw.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19726006/GettyImages_907708340_bw.jpg)

Politics

Politics Briefing: Labour leader targets Poilievre, calls him 'anti-worker politician' – The Globe and Mail

Hello,

Pierre Poilievre is a fraud when it comes to empowering workers, says the president of Canada’s largest labour organization.

Bea Bruske, president of the Canadian Labour Congress, targeted the federal Conservative Leader in a speech in Ottawa today as members of the labour movement met to develop a strategic approach to the next federal election, scheduled for October, 2025.

“Whatever he claims today, Mr. Poilievre has a consistent 20-year record as an anti-worker politician,” said Bruske, whose congress represents more than three million workers.

She rhetorically asked whether the former federal cabinet minister has ever walked a picket line, or supported laws to strengthen workers’ voices.

“Mr. Poilievre sure is fighting hard to get himself power, but he’s never fought for worker power,” she said.

“We must do everything in our power to expose Pierre Poilievre as the fraud that he is.”

The Conservative Leader, whose party is running ahead of its rivals in public-opinion polls, has declared himself a champion of “the common people,” and been courting the working class as he works to build support.

Mr. Poilievre’s office today pushed back on the arguments against him.

Sebastian Skamski, media-operations director, said Mr. Poilievre, unlike other federal leaders, is connecting with workers.

In a statement, Skamski said NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh has sold out working Canadians by co-operating with the federal Liberal government, whose policies have created challenges for Canadian workers with punishing taxes and inflation.

“Pierre Poilievre is the one listening and speaking to workers on shop floors and in union halls from coast to coast to coast,” said Mr. Skamski.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Mr. Singh are scheduled to speak to the gathering today. Mr. Poilievre was not invited to speak.

Asked during a post-speech news conference about the Conservative Leader’s absence, Bruske said the gathering is focused on worker issues, and Poilievre’s record as an MP and in government shows he has voted against rights, benefits and wage increases for workers.

“We want to make inroads with politicians that will consistently stand up for workers, and consistently engage with us,” she said.

This is the daily Politics Briefing newsletter, written by Ian Bailey. It is available exclusively to our digital subscribers. If you’re reading this on the web, subscribers can sign up for the Politics newsletter and more than 20 others on our newsletter signup page. Have any feedback? Let us know what you think.

TODAY’S HEADLINES

Pierre Poilievre’s top adviser not yet contacted in Lobbying Commissioner probe: The federal Lobbying Commissioner has yet to be in touch with Jenni Byrne as the watchdog probes allegations of inappropriate lobbying by staff working both in Byrne’s firm and a second one operating out of her office.

Métis groups will trudge on toward self-government as bill faces another setback: Métis organizations in Ontario and Alberta say they’ll stay on the path toward self-government, despite the uncertain future of a contentious bill meant to do just that.

Liberals buck global trend in ‘doubling down’ on foreign aid, as sector urges G7 push: The federal government pledged in its budget this week to increase humanitarian aid by $150-million in the current fiscal year and $200-million the following year.

Former B.C. finance minister running for the federal Conservatives: Mike de Jong says he will look to represent the Conservatives in Abbotsford-South Langley, which is being created out of part of the Abbotsford riding now held by departing Tory MP Ed Fast.

Ottawa’s new EV tax credit raises hope of big new Honda investment: The proposed measure would provide companies with a 10-per-cent rebate on the costs of constructing new buildings to be used in the electric-vehicle supply chain. Story here.

Sophie Grégoire Trudeau embraces uncertainty in new memoir, Closer Together: “I’m a continuous, curious, emotional adventurer and explorer of life and relationships,” Grégoire Trudeau told The Globe and Mail during a recent interview. “I’ve always been curious and interested and fascinated by human contact.”

TODAY’S POLITICAL QUOTES

“Sometimes you’re in a situation. You just can’t win. You say one thing. You get one community upset. You say another. You get another community upset.” – Ontario Premier Doug Ford, at a news conference in Oakville today, commenting on the Ontario legislature Speaker banning the wearing in the House of the traditional keffiyeh scarf. Ford opposes the ban, but it was upheld after the news conference in the provincial legislature.

“No, I plan to be a candidate in the next election under Prime Minister Trudeau’s leadership. I’m very happy. I’m excited about that. I’m focused on the responsibilities he gave me. It’s a big job. I’m enjoying it and I’m optimistic that our team and the Prime Minister will make the case to Canadians as to why we should be re-elected.” – Public Safety Minister Dominic LeBlanc, before Question Period today, on whether he is interested in the federal Liberal leadership, and succeeding Justin Trudeau as prime minister.

THIS AND THAT

Today in the Commons: Projected Order of Business at the House of Commons, April. 18, accessible here.

Deputy Prime Minister’s Day: Private meetings in Burlington, Ont., then Chrystia Freeland toured a manufacturing facility, discussed the federal budget and took media questions. Freeland then travelled to Washington, D.C., for spring meetings of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group. Freeland also attended a meeting of the Five Eyes Finance Ministers hosted by U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, and held a Canada-Ukraine working dinner on mobilizing Russian assets in support of Ukraine.

Ministers on the Road: Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly is on the Italian island of Capri for the G7 foreign ministers’ meeting. Heritage Minister Pascale St-Onge, in the Quebec town of Farnham, made an economic announcement, then held a brief discussion with agricultural workers and took media questions. Privy Council President Harjit Sajjan made a federal budget announcement in the Ontario city of Welland. Families Minister Jenna Sudds made an economic announcement in the Ontario city of Belleville.

Commons Committee Highlights: Treasury Board President Anita Anand appeared before the public-accounts committee on the auditor-general’s report on the ArriveCan app, and Karen Hogan, Auditor-General of Canada, later appeared on government spending. Crown-Indigenous Relations Minister Gary Anandasangaree appears before the status-of-women committee on the Red Dress Alert. Competition Bureau Commissioner Matthew Boswell and Yves Giroux, the Parliamentary Budget Officer, appeared before the finance committee on Bill C-59. Former Prince Edward Island premier Robert Ghiz, now the president and chief executive officer of the Canadian Telecommunications Association, is among the witnesses appearing before the human-resources committee on Bill C-58, An act to amend the Canada Labour Code. Caroline Maynard, Canada’s Information Commissioner, appears before the access-to-information committee on government spending. Michel Patenaude, chief inspector at the Sûreté du Québec, appeared before the public-safety committee on car thefts in Canada.

In Ottawa: Governor-General Mary Simon presented the Governor-General’s Literary Awards during a ceremony at Rideau Hall, and, in the evening, was scheduled to speak at the 2024 Indspire Awards to honour Indigenous professionals and youth.

PRIME MINISTER’S DAY

Justin Trudeau met with Ottawa Mayor Mark Sutcliffe at city hall. Sutcliffe later said it was the first time a sitting prime minister has visited city hall for a meeting with the mayor. Later, Trudeau delivered remarks to a Canada council meeting of the Canadian Labour Congress.

LEADERS

Bloc Québécois Leader Yves-François Blanchet held a media scrum at the House of Commons ahead of Question Period.

Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre attends a party fundraising event at a private residence in Mississauga.

Green Party Leader Elizabeth May attended the House of Commons.

NDP Leader Jagmeet Singh, in Ottawa, met with Saskatchewan’s NDP Leader, Carla Beck, and, later, Ken Price, the chief of the K’ómoks First Nation,. In the afternoon, he delivered a speech to a Canadian Labour Congress Canadian council meeting.

THE DECIBEL

On today’s edition of The Globe and Mail podcast, Sanjay Ruparelia, an associate professor at Toronto Metropolitan University and Jarislowsky Democracy Chair, explains why India’s elections matter for democracy – and the balance of power for the rest of the world. The Decibel is here.

PUBLIC OPINION

Declining trust in federal and provincial governments: A new survey finds a growing proportion of Canadians do not trust the federal or provincial governments to make decisions on health care, climate change, the economy and immigration.

OPINION

On Haida Gwaii, an island of change for Indigenous land talks

“For more than a century, the Haida Nation has disputed the Crown’s dominion over the land, air and waters of Haida Gwaii, a lush archipelago roughly 150 kilometres off the coast of British Columbia. More than 20 years ago, the First Nation went to the Supreme Court of Canada with a lawsuit that says the islands belong to the Haida, part of a wider legal and political effort to resolve scores of land claims in the province. That case has been grinding toward a conclusion that the B.C. government was increasingly convinced would end in a Haida victory.” – The Globe and Mail Editorial Board.

The RCMP raid the home of ArriveCan contractor as Parliament scolds

“The last time someone was called before the bar of the House of Commons to answer MPs’ inquiries, it was to demand that a man named R.C. Miller explain how his company got government contracts to supply lights, burners and bristle brushes for lighthouses. That was 1913. On Wednesday, Kristian Firth, the managing partner of GCStrategies, one of the key contractors on the federal government’s ArriveCan app, was called to answer MPs’ queries. Inside the Commons, it felt like something from another century.” – Campbell Clark

First Nations peoples have lost confidence in Thunder Bay’s police force

“Thunder Bay has become ground zero for human-rights violations against Indigenous Peoples in Canada. Too many sudden and suspicious deaths of Indigenous Peoples have not been investigated properly. There have been too many reports on what is wrong with policing in the city – including ones by former chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Murray Sinclair and former Toronto Police board chair Alok Mukherjee, and another one called “Broken Trust,” in which the Office of the Independent Police Review Director said the Thunder Bay Police Service (TBPS) was guilty of “systemic racism” in 2018. – Tanya Talaga.

The failure of Canada’s health care system is a disgrace – and a deadly one

“What can be said about Canada’s health care system that hasn’t been said countless times over, as we watch more and more people suffer and die as they wait for baseline standards of care? Despite our delusions, we don’t have “world-class” health care, as our Prime Minister has said; we don’t even have universal health care. What we have is health care if you’re lucky, or well connected, or if you happen to have a heart attack on a day when your closest ER is merely overcapacity as usual, and not stuffed to the point of incapacitation.” – Robyn Urback.

Got a news tip that you’d like us to look into? E-mail us at tips@globeandmail.com. Need to share documents securely? Reach out via SecureDrop.

Politics

GOP strategist reacts to Trump’s ‘unconventional’ request – CNN

GOP strategist reacts to Trump’s ‘unconventional’ request

Donald Trump’s campaign is asking Republican candidates and committees using the former president’s name and likeness to fundraise to give at least 5% of what they raise to the campaign, according to a letter obtained by CNN. CNN’s Steve Contorno and Republican strategist Rina Shah weigh in.

Politics

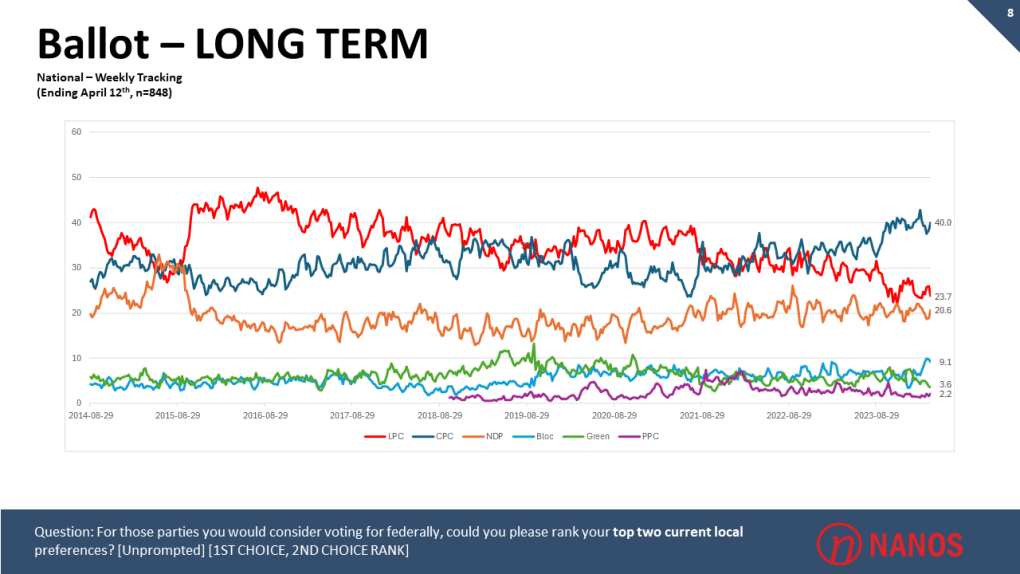

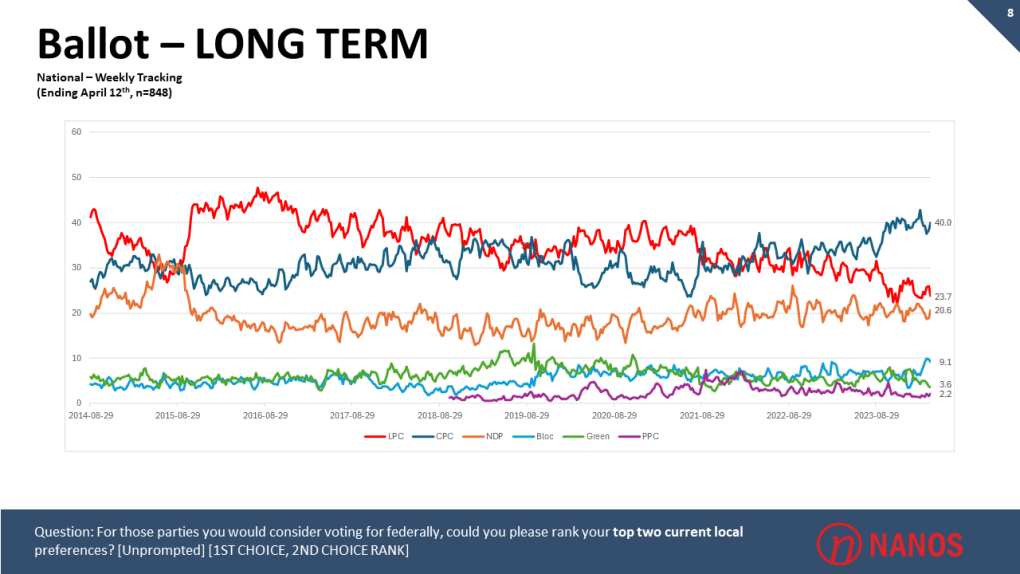

Anger toward federal government at 6-year high: Nanos survey – CTV News

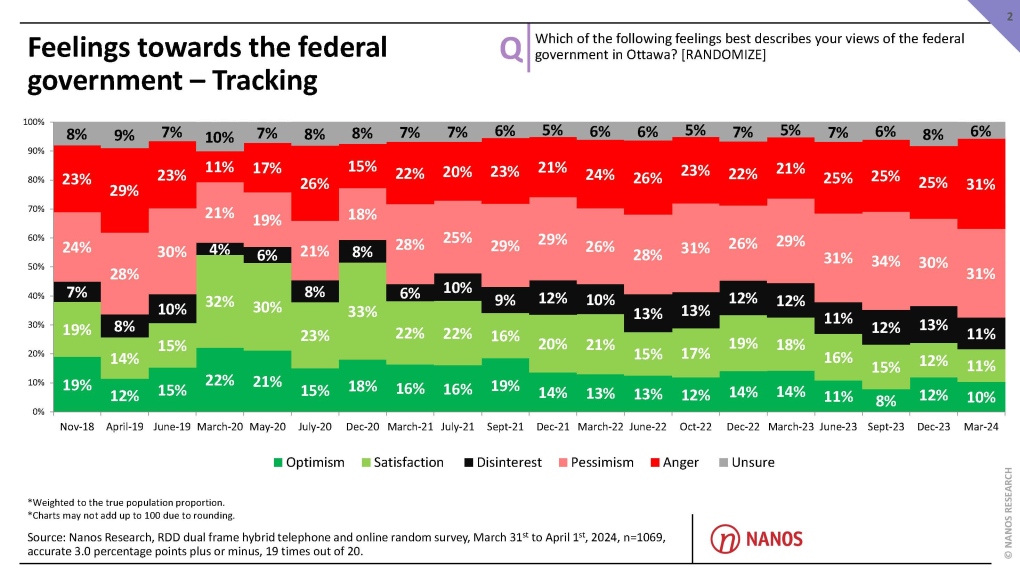

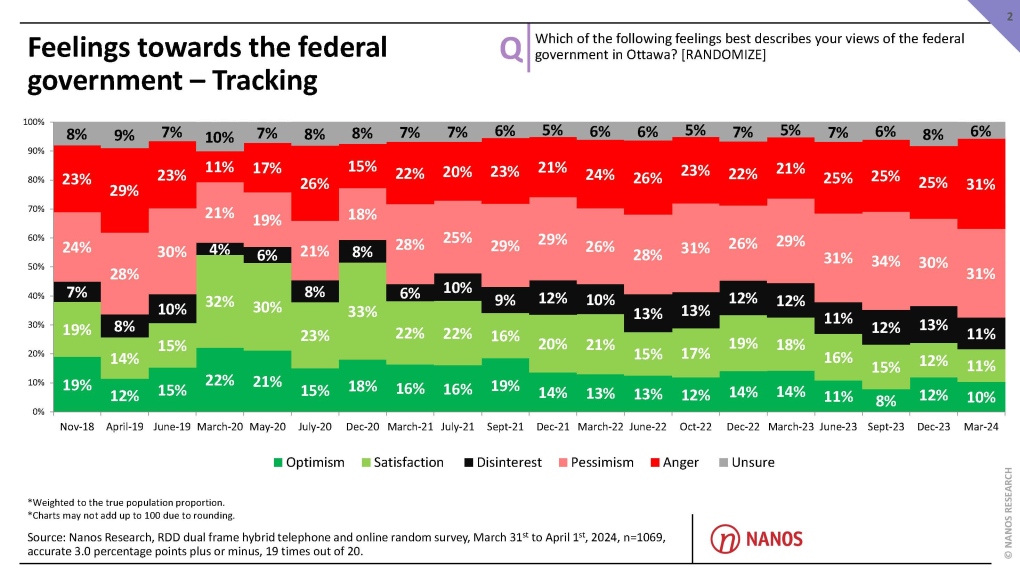

Most Canadians in March reported feeling angry or pessimistic towards the federal government than at any point in the last six years, according to a survey by Nanos Research.

Nanos has been measuring Canadians’ feelings of optimism, satisfaction, disinterest, anger, pessimism and uncertainty toward the federal government since November 2018.

The latest survey found that optimism had crept up slightly to 10 per cent since hitting an all-time low of eight per cent in September 2023.

However, 62 per cent of Canadians said they feel either pessimistic or angry, with respondents equally split between the two sentiments.

(Nanos Research)

“What we’ve seen is the anger quotient has hit a new record,” Nik Nanos, CTV’s official pollster and Nanos Research founder, said in an interview with CTV News’ Trend Line on Wednesday.

Only 11 per cent of Canadians felt satisfied, while another 11 per cent said they were disinterested.

Past survey results show anger toward the federal government has increased or held steady across the country since March 2023, while satisfaction has gradually declined.

Will the budget move the needle?

Since the survey was conducted before the federal government released its 2024 budget, there’s a chance the anger and pessimism of March could subside a little by the time Nanos takes the public’s temperature again. They could also stick.

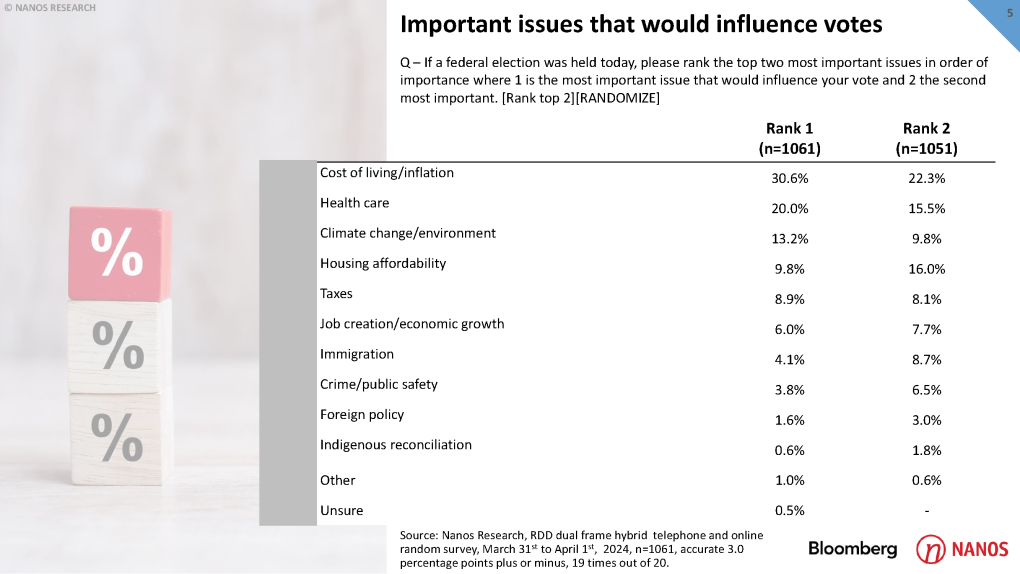

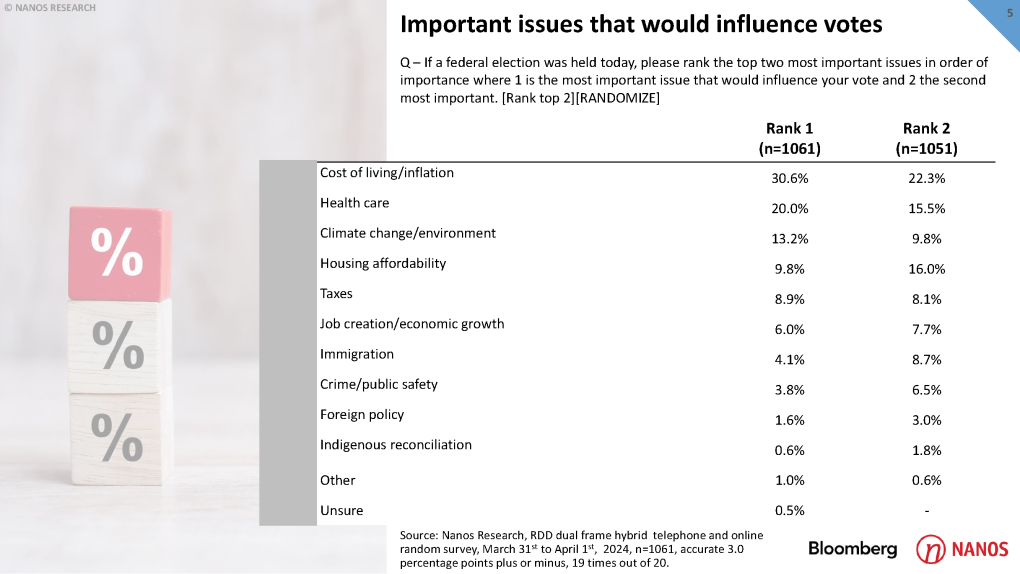

The five most important issues to Canadians right now that would influence votes, according to another recent Nanos survey conducted for Bloomberg, include inflation and the cost of living, health care, climate change and the environment, housing affordability and taxes.

With this year’s budget, the federal government pledged $52.9 billion in new spending while promising to maintain the 2023-24 federal deficit at $40.1 billion. The federal deficit is projected to be $39.8 billion in 2024-25.

The budget includes plans to boost new housing stock, roll out a national disability benefit, introduce carbon rebates for small businesses and increase taxes on Canada’s top-earners.

However, advocacy groups have complained it doesn’t do enough to address climate change, or support First Nations communities and Canadians with disabilities.

“Canada is poised for another disastrous wildfire season, but this budget fails to give the climate crisis the attention it urgently deserves,” Keith Brooks, program director for Environmental Defence, wrote in a statement on the organization’s website.

Meanwhile, when it comes to a promise to close what the Assembly of First Nations says is a sprawling Indigenous infrastructure gap, the budget falls short by more than $420 billion. And while advocacy groups have praised the impending roll-out of the Canada Disability Benefit, organizations like March of Dimes Canada and Daily Bread Food Bank say the estimated maximum benefit of $200 per month per recipient won’t be enough to lift Canadians with disabilities out of poverty.

According to Nanos, if Wednesday’s budget announcement isn’t enough to restore the federal government’s favour, no amount of spending will do the trick.

“If the Liberal numbers don’t move up after this, perhaps the listening lesson for the Liberals will be (that) spending is not the political solution for them to break this trend line,” Nanos said. “It’ll have to be something else.”

Conservatives in ‘majority territory’

While the Liberal party waits to see what kind of effect its budget will have on voters, the Conservatives are enjoying a clear lead when it comes to ballot tracking.

“Any way you cut it right now, the Conservatives are in the driver’s seat,” Nanos said. “They’re in majority territory.”

According to Nanos Research ballot tracking from the week ending April 12, the Conservatives are the top choice for 40 per cent of respondents, the Liberals for 23.7 per cent and the NDP for 20.6 per cent.

Whether the Liberals or the Conservatives form the next government will come down, partly, to whether voters believe more government spending is, or isn’t, the key to helping working Canadians, Nanos said.

“Both of the parties are fighting for working Canadians … and we have two competing visions for that. For the Liberals, it’s about putting government support into their hands and creating social programs to support Canadians,” he said.

“For the Conservatives, it’s very different. It’s about reducing the size of government (and) reducing taxes.”

Watch the full episode of Trend Line in our video player at the top of this article. You can also listen in our audio player below, or wherever you get your podcasts. The next episode comes out Wednesday, May 1.

Methodology

Nanos conducted an RDD dual frame (land- and cell-lines) hybrid telephone and online random survey of 1,069 Canadians, 18 years of age or older, between March 31 and April 1, 2024, as part of an omnibus survey. Participants were randomly recruited by telephone using live agents and administered a survey online. The sample included both land- and cell-lines across Canada. The results were statistically checked and weighted by age and gender using the latest census information and the sample is geographically stratified to be representative of Canada. The margin of error for this survey is ±3.0 percentage points, 19 times out of 20.

With files from The Canadian Press, CTV News Senior Digital Parliamentary Reporter Rachel Aiello and CTV News Parliamentary Bureau Writer, Producer Spencer Van Dyke

-

Science6 hours ago

Science6 hours agoJeremy Hansen – The Canadian Encyclopedia

-

Tech24 hours ago

Tech24 hours agoCytiva Showcases Single-Use Mixing System at INTERPHEX 2024 – BioPharm International

-

Health20 hours ago

Health20 hours agoSupervised consumption sites urgently needed, says study – Sudbury.com

-

Investment6 hours ago

Investment6 hours agoUK Mulls New Curbs on Outbound Investment Over Security Risks – BNN Bloomberg

-

News19 hours ago

Canada's 2024 budget announces 'halal mortgages'. Here's what to know – National Post

-

News18 hours ago

2024 federal budget's key takeaways: Housing and carbon rebates, students and sin taxes – CBC News

-

Science19 hours ago

Science19 hours agoGiant, 82-foot lizard fish discovered on UK beach could be largest marine reptile ever found – Livescience.com

-

Tech22 hours ago

Tech22 hours agoNew EV features for Google Maps have arrived. Here’s how to use them. – The Washington Post