Economy

In an Unequal Economy, the Poor Face Inflation Now and Job Loss Later – The New York Times

For Theresa Clarke, a retiree in New Canaan, Conn., the rising cost of living means not buying Goldfish crackers for her disabled daughter because a carton costs $11.99 at her local Stop & Shop. It means showering at the YMCA to save on her hot water bill. And it means watching her bank account dwindle to $50 because, as someone on a fixed income who never made much money to start with, there aren’t many other places she can trim her spending as prices rise.

“There is nothing to cut back on,” she said.

Jordan Trevino, 28, who recently took a better paying job in advertising in Los Angeles with a $100,000 salary, is economizing in little ways — ordering a cheaper entree when out to dinner, for example. But he is still planning a wedding next year and a honeymoon in Italy.

And David Schoenfeld, who made about $250,000 in retirement income and consulting fees last year and has about $5 million in savings, hasn’t pared back his spending. He has just returned from a vacation in Greece, with his daughter and two of his grandchildren.

“People in our group are not seeing this as a period of sacrifice,” said Mr. Schoenfeld, who lives in Sharon, Mass., and is a member of a group called Responsible Wealth, a network of rich people focused on inequality that pushes for higher taxes, among other stances. “We notice it’s expensive, but it’s kind of like: I don’t really care.”

Higher-income households built up savings and wealth during the early stages of the pandemic as they stayed at home and their stocks, houses and other assets rose in value. Between those stockpiles and solid wage growth, many have been able to keep spending even as costs climb. But data and anecdotes suggest that lower-income households, despite the resilient job market, are struggling more profoundly with inflation.

That divergence poses a challenge for the Federal Reserve, which is hoping that higher interest rates will slow consumer spending and ease pressure on prices across the economy. Already, there are signs that poorer families are cutting back. If richer families don’t pull back as much — if they keep going on vacations, dining out and buying new cars and second homes — many prices could keep rising. The Fed might need to raise interest rates even more to bring inflation under control, and that could cause a sharper slowdown.

In that case, poorer families will almost certainly bear the brunt again, because low-wage workers are often the first to lose hours and jobs. The bifurcated economy, and the policy decisions that stem from it, could become a double whammy for them, inflicting higher costs today and unemployment tomorrow.

“That’s the perfect storm, if unemployment increases,” said Mark Brown, chief executive of West Houston Assistance Ministries, which provides food, rental assistance and other forms of aid to people in need. “So many folks are so very close to the edge.”

America’s poor have spent part of the savings they amassed during coronavirus lockdowns, and their wages are increasingly struggling to keep up with — or falling behind — price increases. Because such a big chunk of their budgets is devoted to food and housing, lower-income families have less room to cut back before they have to stop buying necessities. Some are taking on credit card debt, cutting back on shopping and restaurant meals, putting off replacing their cars or even buying fewer groceries.

But while lower-income families spend more of each dollar they earn, the rich and middle classes have so much more money that they account for a much bigger share of spending in the overall economy: The top two-fifths of the income distribution account for about 60 percent of spending in the economy, the bottom two-fifths about 22 percent. That means the rich can continue to fuel the economy even as the poor pull back, a potential difficulty for policymakers.

The Federal Reserve has been lifting interest rates rapidly since March to try to slow consumer spending and raise the cost of borrowing for companies, which will in turn lead to fewer business expansions, less hiring and slower wage growth. The goal is to slow the economy enough to lower inflation but not so much that it causes a painful recession.

But job growth accelerated unexpectedly in July, with wages climbing rapidly. Consumer spending, adjusted for inflation, has cooled, but Americans continue to open their wallets for vacations, restaurant meals and other services. If solid demand and tight labor market conditions continue, they could help to keep inflation rapid and make it more difficult for the Fed to cool the economy without continuing its string of quick rate increases. That could make widespread layoffs more likely.

“The one, singular worry is the jobs market — if demand is constrained to the point that companies have to start laying off workers, that’s what hits Main Street,” said Nela Richardson, chief economist at the job market data provider ADP. “That’s what hits low-income workers.”

Lower-income people are already hurting. Mr. Brown’s organization has seen more requests for help in recent months, he said, as local families fall behind on their bills. The size of the typical request has gone up, too, from a few hundred dollars to a few thousand. And he has noticed financial pain creeping up the income spectrum.

Mr. Brown’s observations are backed up by government data: About 12 percent of households reported they were struggling to get enough to eat in early July, up from about 10 percent at the beginning of the year, according to the Census Bureau.

Families can’t easily cut back what they spend on rent, gas or electricity as those prices climb, said Brian Greene, chief executive of the Houston Food Bank, which provides food to Mr. Brown’s organization and other charities across the region. So they cut back on food.

“Food insecurity isn’t about food,” Mr. Greene said. “Food insecurity is about income.”

Many poorer families’ incomes held up relatively well early in the pandemic because government aid — expanded unemployment benefits, stimulus checks and other programs — helped offset lost wages when businesses shut down. Then, as the economy reopened, pay soared for restaurant workers, delivery drivers and other low-wage workers.

But pandemic aid programs have ended and wage growth is slowing in many sectors — average hourly earnings in leisure and hospitality, which rose rapidly last year, actually fell in July from a month earlier for rank-and-file workers. Prices have risen so fast that even unusually quick wage growth has failed to keep up.

The gaping divide between the rich and the poor in this inflationary moment is clear in corporate earnings calls. At Boot Barn, a Western wear retailer, sales of men’s Western boots were down in the first quarter, but sales of higher-priced exotic skin boots picked up. At LVMH, which owns luxury brands like Louis Vuitton and Tiffany, American revenues have been growing strongly, while at Walmart, customers are pulling back as they struggle to afford basic necessities, particularly food, which has run up sharply in price.

“This is affecting customers’ ability to spend on general merchandise categories and requiring more markdowns to move through the inventory, particularly apparel,” Walmart said in its July 25 guidance.

It’s not just apparel: Consumers across the economy are buying less milk and fewer eggs, as prices for those products rise significantly, according to an analysis of government figures by Michelle Meyer, chief U.S. economist for Mastercard. Yet they are also going out to eat at restaurants more often.

The fissures are clear in the car market. Demand for new cars, which generally sell to higher-income buyers, has remained strong and prices continue to soar amid supply shortages — putting upward pressure on inflation. But used-car demand is ebbing and prices have begun to depreciate again.

“We see bifurcation in many parts of the economy and the auto market,” Jonathan Smoke, chief economist at Cox Automotive, said in an interview. “The new vehicle buyer has shown much less price sensitivity.”

Housing is another realm where fates have diverged. Home costs have run up sharply since the pandemic and mortgages are now more expensive, making buying unaffordable for many families. Because would-be buyers can’t afford homes, they are renting, keeping apartments for lease in short supply and pushing rents ever higher. Those soaring rents hit lower-income households especially hard: Roughly six in 10 people in the bottom quarter of earners rent their homes.

By contrast, homeowners have both seen their houses rise in value and often enjoy a built-in inflation hedge, since many refinanced their mortgages and locked in low monthly payments when rates were low in 2020 and 2021.

“The haves are really comfortable right now,” said Nicole Bachaud, an economist from Zillow, also noting that “we’re going to see this gap getting wider between people who are homeowners and people who are probably never going to be homeowners.”

Ms. Clarke, the New Canaan retiree, recently got off the wait list for an affordable apartment for herself and her 24-year-old daughter, who has autism and cannot work. Their new unit has just one bedroom, but it is clean and has new appliances, and at about $1,350 a month, she can squeeze it into her budget.

The lease lasts only a year, however, and Ms. Clarke is worried about finding somewhere to live if it isn’t renewed. Even now, she is barely making ends meet: She lost her car keys recently and had to spend nearly $500 replacing them, wiping out nearly all her small rainy-day fund and leaving her one crisis away from financial disaster.

“When you don’t have money, you’re on a fixed income, you’re constantly thinking, ‘Well, maybe I shouldn’t have bought that,’” she said. “There’s no cushion. There really never was.”

More financially secure families also face headwinds, of course, which could eventually prompt them to slow down spending. The cash savings they built up during the pandemic won’t last forever, and rising prices could prompt many households to pull back their spending.

And swooning stock markets could prompt richer families, who tend to have more money invested, to spend less than they otherwise would. Some economists think that the people in this demographic have mostly kept spending recently — despite their falling economic confidence — because they are eager to take vacations that they had put off earlier in the pandemic.

“Where I’m budgeting, it’s to make room for travel,” said Mr. Trevino of Los Angeles. “I feel like I’ve missed out on that a little bit.”

Economists have speculated that richer consumers’ resilience could fade as autumn approaches and they take stock of their finances amid a slowing economy. But for now, the reality that America’s wealthier consumers have yet to sharply pull back in the face of rising prices may be setting up a tough road ahead for the nation’s poorer ones.

“We really, in a way, haven’t noticed the inflation very much,” Mr. Schoenfeld said. “This economy is very unfair.”

Jason Karaian contributed reporting.

Economy

Climate Change Will Cost Global Economy $38 Trillion Every Year Within 25 Years, Scientists Warn – Forbes

Topline

Climate change is on track to cost the global economy $38 trillion a year in damages within the next 25 years, researchers warned on Wednesday, a baseline that underscores the mounting economic costs of climate change and continued inaction as nations bicker over who will pick up the tab.

Key Facts

Damages from climate change will set the global economy back an estimated $38 trillion a year by 2049, with a likely range of between $19 trillion and $59 trillion, warned a trio of researchers from Potsdam and Berlin in Germany in a peer reviewed study published in the journal Nature.

To obtain the figure, researchers analyzed data on how climate change impacted the economy in more than 1,600 regions around the world over the past 40 years, using this to build a model to project future damages compared to a baseline world economy where there are no damages from human-driven climate change.

The model primarily considers the climate damages stemming from changes in temperature and rainfall, the researchers said, with first author Maximilian Kotz, a researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, noting these can impact numerous areas relevant to economic growth like “agricultural yields, labor productivity or infrastructure.”

Importantly, as the model only factored in data from previous emissions, these costs can be considered something of a floor and the researchers noted the world economy is already “committed to an income reduction of 19% within the next 26 years,” regardless of what society now does to address the climate crisis.

Global costs are likely to rise even further once other costly extremes like weather disasters, storms and wildfires that are exacerbated by climate change are considered, Kotz said.

The researchers said their findings underscore the need for swift and drastic action to mitigate climate change and avoid even higher costs in the future, stressing that a failure to adapt could lead to average global economic losses as high as 60% by 2100.

!function(n) if(!window.cnxps) window.cnxps=,window.cnxps.cmd=[]; var t=n.createElement(‘iframe’); t.display=’none’,t.onload=function() var n=t.contentWindow.document,c=n.createElement(‘script’); c.src=’//cd.connatix.com/connatix.playspace.js’,c.setAttribute(‘defer’,’1′),c.setAttribute(‘type’,’text/javascript’),n.body.appendChild(c) ,n.head.appendChild(t) (document);

(function()

function createUniqueId()

return ‘xxxxxxxx-xxxx-4xxx-yxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx’.replace(/[xy]/g, function(c) 0,

v = c == ‘x’ ? r : (r & 0x3 );

const randId = createUniqueId();

document.getElementsByClassName(‘fbs-cnx’)[0].setAttribute(‘id’, randId);

document.getElementById(randId).removeAttribute(‘class’);

(new Image()).src = ‘https://capi.connatix.com/tr/si?token=546f0bce-b219-41ac-b691-07d0ec3e3fe1’;

cnxps.cmd.push(function ()

cnxps(

playerId: ‘546f0bce-b219-41ac-b691-07d0ec3e3fe1’,

storyId: ”

).render(randId);

);

)();

How Do The Costs Of Inaction Compare To Taking Action?

Cost is a major sticking point when it comes to concrete action on climate change and money has become a key lever in making climate a “culture war” issue. The costs and logistics involved in transitioning towards a greener, more sustainable economy and moving to net zero are immense and there are significant vested interests such as the fossil fuel industry, which is keen to retain as much of the profitable status quo for as long as possible. The researchers acknowledged the sizable costs of adapting to climate change but said inaction comes with a cost as well. The damages estimated already dwarf the costs associated with the money needed to keep climate change in line with the limits set out in the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement, the researchers said, referencing the globally agreed upon goalpost set to minimize damage and slash emissions. The $38 trillion estimate for damages is already six times the $6 trillion thought needed to meet that threshold, the researchers said.

Crucial Quote

“We find damages almost everywhere, but countries in the tropics will suffer the most because they are already warmer,” said study author Anders Levermann. The researcher, also of the Potsdam Institute, explained there is a “considerable inequity of climate impacts” around the world and that “further temperature increases will therefore be most harmful” in tropical countries. “The countries least responsible for climate change” are expected to suffer greater losses, Levermann added, and they are “also the ones with the least resources to adapt to its impacts.”

What To Watch For

The fundamental inequality over who is impacted most by climate change and who has benefited most from the polluting practices responsible for the climate crisis—who also have more resources to mitigate future damages—has become one of the most difficult political sticking points when it comes to negotiating global action to reduce emissions. Less affluent countries bearing the brunt of climate change argue wealthy nations like the U.S. and Western Europe have already reaped the benefits from fossil fuels and should pay more to cover the losses and damages poorer countries face, as well as to help them with the costs of adapting to greener sources of energy. Other countries, notably big polluters India and China, stymie negotiations by arguing they should have longer to wean themselves off of fossil fuels as their emissions actually pale in comparison to those of more developed countries when considered in historical context and on a per capita basis. Climate financing is expected to be key to upcoming negotiations at the United Nations’s next climate summit in November. The COP29 summit will be held in Baku, the capital city of oil-rich Azerbaijan.

Further Reading

Economy

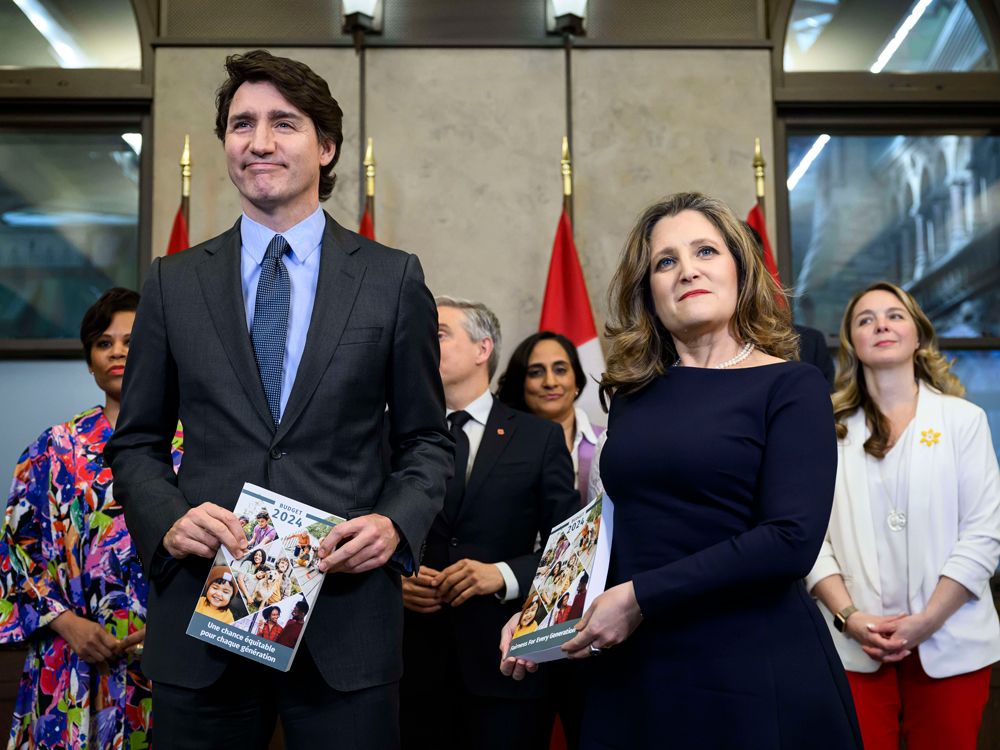

Canada's budget 2024 and what it means for the economy – Financial Post

THIS CONTENT IS RESERVED FOR SUBSCRIBERS ONLY

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Exclusive articles from Barbara Shecter, Joe O’Connor, Gabriel Friedman, Victoria Wells and others.

- Daily content from Financial Times, the world’s leading global business publication.

- Unlimited online access to read articles from Financial Post, National Post and 15 news sites across Canada with one account.

- National Post ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition to view on any device, share and comment on.

- Daily puzzles, including the New York Times Crossword.

SUBSCRIBE TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES

Subscribe now to read the latest news in your city and across Canada.

- Exclusive articles from Barbara Shecter, Joe O’Connor, Gabriel Friedman, Victoria Wells and others.

- Daily content from Financial Times, the world’s leading global business publication.

- Unlimited online access to read articles from Financial Post, National Post and 15 news sites across Canada with one account.

- National Post ePaper, an electronic replica of the print edition to view on any device, share and comment on.

- Daily puzzles, including the New York Times Crossword.

REGISTER / SIGN IN TO UNLOCK MORE ARTICLES

Create an account or sign in to continue with your reading experience.

- Access articles from across Canada with one account.

- Share your thoughts and join the conversation in the comments.

- Enjoy additional articles per month.

- Get email updates from your favourite authors.

Economy

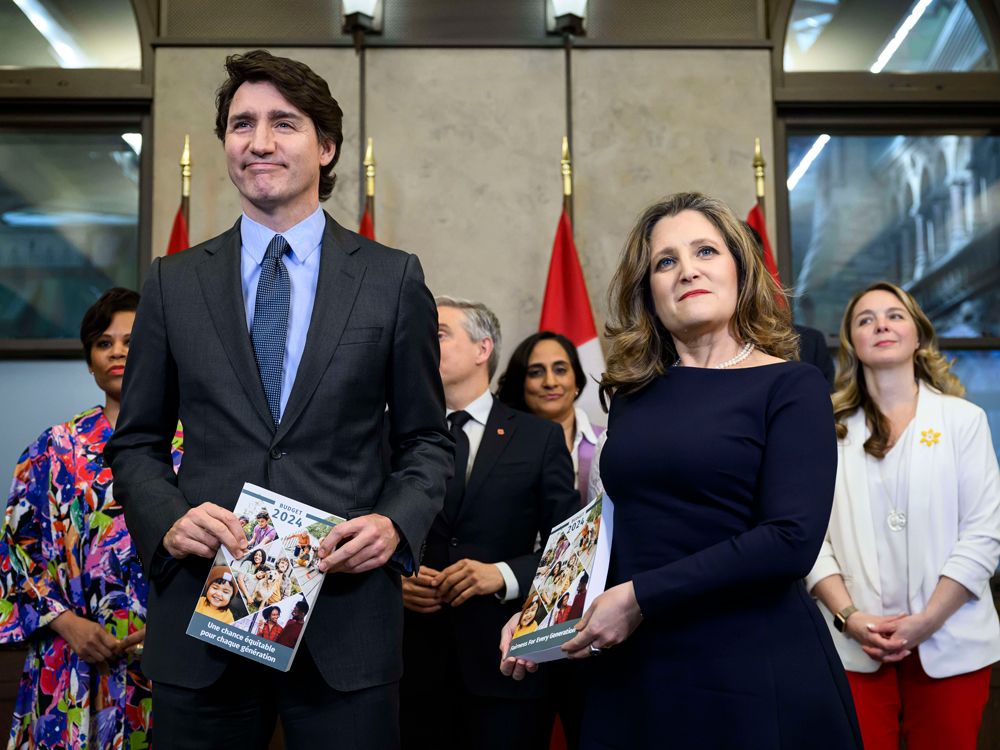

Opinion: Canada's economy has stagnated despite Trudeau government spin – Financial Post

Article content

Growth in gross domestic product (GDP), the total value of all goods and services produced in the economy annually, is one of the most frequently cited indicators of economic performance. To assess Canadian living standards and the current health of the economy, journalists, politicians and analysts often compare Canada’s GDP growth to growth in other countries or in Canada’s past. But GDP is misleading as a measure of living standards when population growth rates vary greatly across countries or over time.

Article content

Federal Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland recently boasted that Canada had experienced the “strongest economic growth in the G7” in 2022. In this she echoes then-prime minister Stephen Harper, who said in 2015 that Canada’s GDP growth was “head and shoulders above all our G7 partners over the long term.”

Article content

Unfortunately, such statements do more to obscure public understanding of Canada’s economic performance than enlighten it. Lately, our aggregate GDP growth has been driven primarily by population and labour force growth, not productivity improvements. It is not mainly the result of Canadians becoming better at producing goods and services and thus generating more real income for their families. Instead, it is a result of there simply being more people working. That increases the total amount of goods and services produced but doesn’t translate into increased living standards.

Let’s look at the numbers. From 2000 to 2023 Canada’s annual average growth in real (i.e., inflation-adjusted) GDP growth was the second highest in the G7 at 1.8 per cent, just behind the United States at 1.9 per cent. That sounds good — until you adjust for population. Then a completely different story emerges.

Article content

Over the same period, the growth rate of Canada’s real per person GDP (0.7 per cent) was meaningfully worse than the G7 average (1.0 per cent). The gap with the U.S. (1.2 per cent) was even larger. Only Italy performed worse than Canada.

Why the inversion of results from good to bad? Because Canada has had by far the fastest population growth rate in the G7, an average of 1.1 per cent per year — more than twice the 0.5 per cent experienced in the G7 as a whole. In aggregate, Canada’s population increased by 29.8 per cent during this period, compared to just 11.5 per cent in the entire G7.

Starting in 2016, sharply higher rates of immigration have led to a pronounced increase in Canada’s population growth. This increase has obscured historically weak economic growth per person over the same period. From 2015 to 2023, under the Trudeau government, real per person economic growth averaged just 0.3 per cent. That compares with 0.8 per cent annually under Brian Mulroney, 2.4 per cent under Jean Chrétien and 2.0 per cent under Paul Martin.

Recommended from Editorial

Canada is neither leading the G7 nor doing well in historical terms when it comes to economic growth measures that make simple adjustments for our rapidly growing population. In reality, we’ve become a growth laggard and our living standards have largely stagnated for the better part of a decade.

Ben Eisen, Milagros Palacios and Lawrence Schembri are analysts at the Fraser Institute.

Bookmark our website and support our journalism: Don’t miss the business news you need to know — add financialpost.com to your bookmarks and sign up for our newsletters here.

Share this article in your social network

-

Sports22 hours ago

Sports22 hours agoTeam Canada’s Olympics looks designed by Lululemon

-

News23 hours ago

Richard Chevolleau Short Film “Marvelous Marvin” Set to go to Camera

-

Business21 hours ago

Firefighters battle wildfire near Edson, Alta., after natural gas line rupture – CBC.ca

-

Tech14 hours ago

Tech14 hours agoiPhone 15 Pro Desperado Mafia model launched at over ₹6.5 lakh- All details about this luxury iPhone from Caviar – HT Tech

-

Investment23 hours ago

Investment23 hours agoStephen Poloz will lead push to boost domestic investment by Canadian pension funds

-

Sports14 hours ago

Sports14 hours agoLululemon unveils Canada's official Olympic kit for the Paris games – National Post

-

News24 hours ago

Federal budget 2024: Some of the winners and losers

-

Investment21 hours ago

Investment21 hours agoWall Street bosses cheer investment banking gains but stay cautious