Art

Is the Art World Entering the Age of ‘Anti-Woke’ Backlash? Here’s Why Today’s Reaction Will Look Very Different From Decades’ Past

|

|

We are in a backlash period—or, at least, the early stages of it, with new consensus about the “excesses” of the social justice movements of the past few years percolating through the discourse. Whether this backlash will look like previous ones is what I have been asked to comment on in this article.

The nostalgia cycle is about 30 years—long enough for the past to feel fresh again as a new generation ages (hence: That ‘90s Show). There is also an edgier kind of political nostalgia cycle. Contemporary debates about representation in the museum are experienced as a repeat of debates over “multiculturalism” from the 1990s, themselves experienced as a return to the combative confrontations of the 1960s. Indeed, so much of the politics of the present feels like a kind of replay of the ‘90s—alt-right “culture wars” as an even darker reboot of Pat Buchanan’s classic ‘90s version; the debates over “wokeness” replaying early-‘90s panics over “political correctness,” etc.

The Trump administration touched off dramatic debates, changing the texture of the conversation within the U.S. art world. Blue-chip galleries added Black artists to their programs, important overlooked female artists have been rediscovered at a brisk clip, museums shook up their schedules, and biennials reversed polarities so that the once-drastically overrepresented white Euro-American male demographic has been rendered a near non-presence in almost every such recent survey, from New York to New Orleans, and from Arkansas to Italy.

Video by Dawoud Bey at the Historic New Orleans Collection during Prospect New Orleans. Photo by Ben Davis.

Yet from the beginning, all this has been haunted by an awareness that backlash is incoming. For art observers looking at the intense focus on identity in recent biennials, the obvious reference is the 1993 Whitney Biennial, the so-called “identity politics biennial” (in fact, the recent 2022 Whitney Biennial self-consciously returned to many of the artists from 1993). This event remains a touchstone, having surfaced a large number of non-white, queer, and feminist voices. The ’93 biennial caught the angry zeitgeist of a liberal art world at the end of 12 years of Reaganite rule, in the wake of the most intense period of the AIDS crisis and the ‘92 conflagration in L.A. (VHS footage of Rodney King being beaten by the LAPD was included in the show.)

It was a watershed. But it was also a high-water mark, signaling the inflection point after which backlash officially took the wheel.

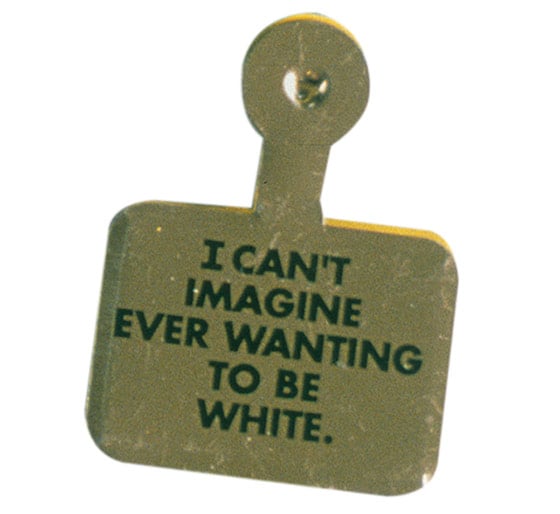

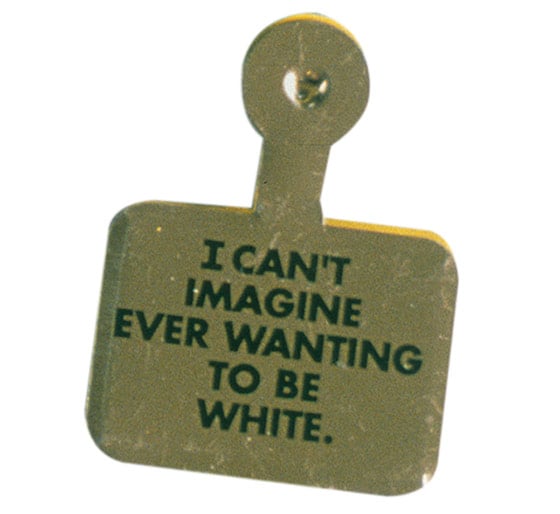

The ’93 biennial was panned by critics. Conceptual artist Daniel J. Martinez produced a series of pins given to Whitney visitors that read “I Can’t Imagine Ever Wanting to Be White.” In Who We Be, Jeff Chang’s history of the rise and cooption of multiculturalism, he quotes Martinez on what came next: “’93 was the last shot of the war. We lost right at the moment we thought we were winning.” Coco Fusco, another star of that show, remembered recently the shift that marked the second half of the decade: “In the art world of the late ‘90s and early ‘00s there was a shift away from the moral argument about empowerment and civil rights, which was widespread in the 1980s and early ‘90s, to an emphasis on visual talent and success.”

Daniel Joseph Martinez created these entry badges for the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1993 biennial exhibition.

Photo courtesy the artist and Simon Preston Gallery, New York.

What can we learn from this moment? How is today different or the same?

An uncomfortable fact is that periods of advance tend to coincide with moments when the kinds of cultural liberals who make up the base of the art world feel that they are in crisis, politically. The spectacle of conservatives in power puts more pressure on culture, as rage at political disempowerment is channeled into gestures of cultural activism and symbolic atonement. The ’90s wave came out of the anger with Reagan and Bush, just as the recent climate grew out of reaction to Trump’s election. (There was some of this vibe under Bush II, but 9/11 and the Iraq War really defined the politics of that period in a different way.)

Conversely, while it flatters the liberal art world to focus on right-wing culture warriors as the driver of regression, it was actually Bill Clinton’s ascent to power in 1992 that was the harbinger of the quietist turn in 1990s cultural discourse. He and the Democratic Leadership Council had made it their mission to represent the Democratic party as pro-business, distancing it from unions and social movements. Toni Morrison may have quipped that Clinton was “the first Black president” in the New Yorker, but during the campaign, Clinton staged his own version of the “culture wars” on Democratic party terrain, deliberately baiting Jesse Jackson into a battle over rapper Sister Souljah and making a big show of condemning “anti-white” rhetoric to prove that he was the safe hand for mainstream (read: white, pro-business, and business-as-usual) America.

As a parallel, more recent talk of a “vibe shift” in culture following the #Resistance moment coincides with the election of Joe Biden, who literally promised on the campaign trail that, were you to elect him, you wouldn’t have to think about politics too much anymore. “The 2010s were such a politicized decade that I think the desire people have to be less constrained by political considerations makes a lot of sense,” Sean Monahan, whose blog 8Ball touched off the “vibe shift” talk, told New York Magazine.

Claire Govender adds the 20,000th book to “Ben Ben Lying Down with Political Books” by Marta Minujin, Photo: Fabio De Paola/PA Wire.

The Burns Halperin Report shows just how vulnerable to rollback recent advances in representation may be. Permanent collections, they show, are not so deeply affected by the social justice zeitgeist—indeed, they are little affected (although contemporary museums seem to be making solid progress towards gender parity in collecting, at least). As one mechanism for this inertia, the report points to the fact that 60 percent of the objects that enter museum collections come from gifts or bequests; these, in turn, presumably form the basis of exhibition programs. Among other things, the blockage thereby represents the embedded malaise and biases of wealth, and its accumulated power (a point theorist Nizan Shaked also argues in her important treatise from this year, Museums and Wealth).

Researching the 1990s backlash, I found this quote from David Lang, the cofounder of the Bang on a Can festival: “If you’re giving an organization $10,000, you can say, ‘In return to that we expect you to have a social face.’ If you’re cutting them from $10,000 to $1,000, you can’t say, ‘Oh by the way for this $1,000 we’d like you to change your organization.’” Lang was speaking about how arts funding cuts took the wind out of the sails of diversification efforts in the mid-‘90s, but the line could also apply to the contemporary challenge of turning arts institutions around despite the considerable reputational and commercial incentives to do so. Compared to the 1990s, even big museums today are actually much more crisis-ridden, symbolized by the last year of protests and strikes over barely livable conditions for ordinary staff.

Without money behind social justice demands, you are left with fleeting gestures and moralistic browbeating, ultimately preparing the ground for cynicism and backlash.

The United States is much less white than it was in 1990s, meaning there is more of a self-interested business case for institutions to change. But on the other hand, inequality is much worse than in the 1990s. Private wealth has today accumulated much more power and is thus even more arrogantly disconnected from the experiences of ordinary people and convinced of its own rightness. How these two dynamics interact is going to shape what the future of what museums look like. My feeling is that they point to an intensified fragmentation of the arts rather than a return to the ideological status quo.

The long-term movement towards a more diverse country is a fact. Even if you are very cynical, it is not impossible to think that bequest patterns will evolve, with a time lag to account for changing generational sensibilities. Since the huge Black Lives Matter protests of 2020, it does feel as if diverse cultural consumption has been firmly established as a virtue for high-status individuals (whether it is embedded remains to be seen).

The Sex and the City revival ‘And Just Like That.’ Courtesy of HBO Max.

Last year’s strange, guilt-ridden Sex in the City reboot, And Just Like That…, had the merit of unintentionally underlining this newly mainstream mindset for premium cable consumers. Erstwhile gallery owner Charlotte proves her good ally status—and relieves the anxiety she and her husband Harry feel at a dinner where they are the only white people—when she explains to her friend’s critical mom that the Black artists her daughter collects are truly investment quality (including “an early Derrick Adams!”)

Still, there is a very real limit to guilting patrons into “Doing Better” on voluntaristic moral grounds. It alienates as many would-be patrons as it moves.

Burns and Halperin write, “At the current rate of change, it may be a simpler task to build entirely new museums and market structures than to create the necessary change within the existing systems.” Melissa Smith has reported on one of the most intriguing developments of the past years: Black artists, experiencing an unprecedented market windfall, are putting funds into building up their own alternative institutions, from Titus Kaphar’s NXTHVN to residencies from Derrick Adams and Mcarthur Binion.

Founder of NXTHVN and artist Titus Kaphar. Photo by John Dennis, courtesy of NXTHVN and Gagosian.

But alternative institution-building is also happening on a much bigger scale—and it is not necessarily progressive. As Georgina Adam writes in her recent book The Rise and Rise of the Private Art Museum, the major trend of the past decade around the world has been stagnation in public museums, and the parallel creation of new personal founder-driven museums (the so-called “ego-seum”), born out of “a distrust of public institutions, and in some cases more problematic aims: self-aggrandizement, hyping the value of their collection, getting better access to desirable art and getting whopping tax breaks.”

Here’s a case study for the limits of the moral appeal to patrons in an age of runaway inequality. Back in 2008, billionaire Eli Broad first backed L.A. MOCA when it needed a bailout, prompting fears, from New York Times critic Roberta Smith, that he would merge “the museum’s exemplary collection of art with his own, more predictable, market-driven one.” That turned out not to be what happened at all. After debates over the museum’s direction, Broad simply withdrew from supporting L.A. MOCA to build his own glitzy Broad Museum across the street—with free admission and Jeff Koonses galore.

Jeff Koons’s tulips sculpture at the Broad. Photo by Santi Visalli/Getty Images.

The new political demands on culture from one direction are likely to produce new cultural moves that are equally unprecedented in the other. Until very recently, you used to be able to assume that Silicon Valley was a lock for liberals. But the kinds of new tech fortunes that the art industry has been unsuccessfully courting for over a decade—the bulk of new wealth creation, before the recent tech downturn—now seem to be flirting with reaction. In opposition to the Bernie Sanders-style social-democratic wave, Black Lives Matter, and #MeToo, techie libertarianism seems to be mutating into a turbo-charged Nietzschean neo-monarchism, militantly hostile to traditional liberal institutions, creating a new political bloc with the alt-right trolls.

Contemporary cultural backlash may not look like a return to a cozy, oblivious cultural center. It may take its cues more from Elon Musk buying Twitter to “defeat the woke mind virus” or Peter Thiel funding an “anti-woke” downtown film festival out of his pocket change.

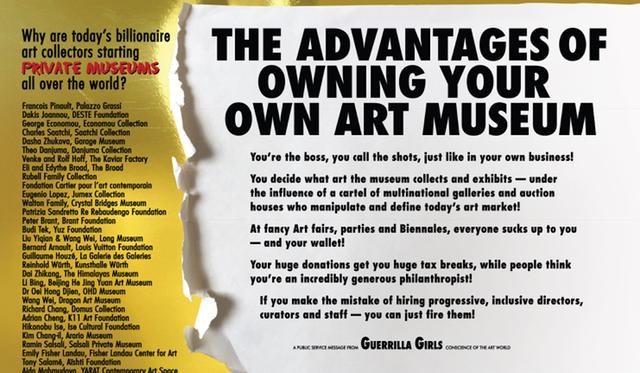

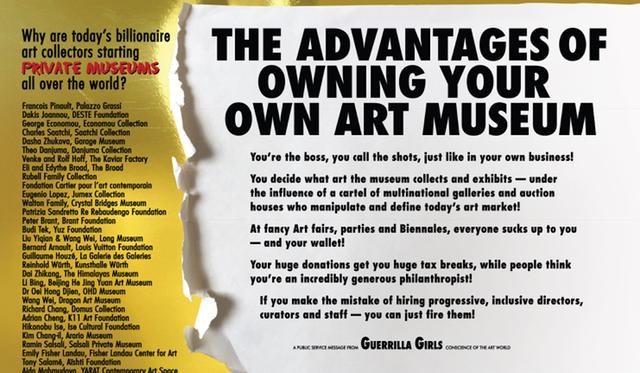

When art observers think of backlash in the 1990s, they often think of the 1995 Whitney Biennial. It is often considered a “return to beauty” biennial, where representation snapped back towards the historical norms after the aberration of ‘93. The Guerrilla Girls printed fliers and posters summing up the feeling, declaring ironically, “Traditional Values and Quality Return to the Whitey [sic] Museum.”

A translation of the Guerrilla Girls’ banner. Photo: Courtesy Guerrilla Girls.

But the more relevant example of culture-wars backlash for today possibly came one year later: the 1996 founding of Fox News. Its boss Roger Ailes had served as a media guru to George H.W. Bush in the period of the infamous, race-baiting Willie Horton ad. He officially ejected himself from politics after Bush’s defeat in the 1992 election. And yet, all that reactionary political energy, instead of being neutralized, deflected into the cultural sphere. In Fox News, Ailes masterminded the creation of a free-standing ideological universe, one that openly challenged the idea that you could assume a mainstream “liberal media bias.” We know what its effects have been.

Given this potential shape of backlash and the structural flaws at the heart of the traditional art system, where to look for hope for real progress? I’ll give the last word to Cornell West. In his 1990 essay on “The New Cultural Politics of Difference,” West described the “double bind” of cultural producers within academia and museums, critical of institutions that they were nevertheless materially dependent on.

I think invoking it here is the opposite of nostalgia—it may be even more apt in the 2020s than it was in 1990s:

Without social movement or political pressure from outside these institutions… transformation degenerates into mere accommodation or sheer stagnation, and the role of the “coopted progressive”—no matter how fervent one’s subversive rhetoric—is rendered more difficult. In this sense there can be no artistic breakthrough or social progress without some form of crisis in civilization—a crisis usually generated by organizations or collectivities that convince ordinary people to put their bodies and lives on the line. There is, of course, no guarantee that such pressure will yield the result one wants, but there is a guarantee that the status quo will remain or regress if no pressure is applied at all.

Art

Art in Bloom returns – CTV News Winnipeg

Art

Crafting the Painterly Art Style in Eternal Strands – IGN First – IGN

Next up in our IGN First coverage of Eternal Strands, we’re diving into the unique and colorful art in the land of the Enclave. We sat down with art director Sebastien Primeau and lead character artist Stephanie Chafe to ask them all about it.

IGN: Let’s talk about Eternal Strands’ distinctive art style. What were some of the guiding principles behind the art direction?

Primeau: I think what was guiding the art direction at the beginning of the project was to find the scale of the game, because we knew that we were having those gigantic 25-meter tall creatures and monsters. So we really wanted to have the architectural elements of the game – the vegetation, the trees – to reflect that kind of size.

So one of my inspirations was coming from an architect called Hugh Ferriss, and I was very impressed by his work, and it was very inspiring for me too. So just the scale of his work. So he was a real influence for Metropolis, Gotham, so I was really inspired by his work.

Chafe: I think one of the things that, just as artists and as creators, we were interested in as well was going for a color palette that can be very bright. And something that can really challenge us too as artists, and going into a bit more of at-hand painterly work, and getting our hands really into it, into the clay, so to speak, and trying to go for something bright and colorful.

IGN: That’s not the first time I’ve heard your team describe the art style as “painterly.” What does that mean?

Primeau: Painterly is just a word that can give so much room to different types of interpretation. I think where we started was Impressionist painters. So I really enjoy looking at many painters, and they have different types of styles. But we wanted to have something that was fresh, colorful, and unique.

And also, I remember when we were starting the project there was that word. “It’s going to be stylized,” but stylized is just a word that gives so much room to different kinds of style. And since we were a small team, we had to figure out a way to create those rough brushstrokes. If it was painted very quickly by an artist, like Bob Ross would say, “Accident is normal.” So I think we wanted to embrace that. And because we’re all artists, it’s hard too, at some point, to disconnect from what you’re doing. It’s like, “Oh, I can maybe add some more details over there.” But I was always the- “Guys, oh, Steph, that’s enough. Let’s stop it right there. I think it looks cool.”

IGN: So, when you create an asset for Eternal Strands, is somebody actually painting something?

Chafe: I can speak more on the character side. For us, we do a lot of that hand painting, a lot of those strokes by hand. And we try to embrace, not the mistakes, but the non-realistic part of it having an extra splotch here and there.

We’ve got brushes that we made that can help us as artists to get the texture we’re looking for. It really is a texture that gives to it. But a lot of the time it’s not just something generated in a substance painter, or getting these things that will layer these things for you, making it quick and procedural. Sometimes we have those as helpers, but more often than not we just go in and paint.

IGN: Eternal Strands is a fair bit more colorful than lots of games today. Why was it important to the team to have lots of bright colors?

Primeau: You need to be careful, actually, with colors. Because with too many colors you can create that kind of pizza of color.

We wanted to balance the color per level, because we’re not making an open-world game. I really wanted each level to have their own color palette identity. So we’re playing a lot with the lighting. The lighting for me is key. It’s very important. You can have gorgeous textures, props, characters, but if your lighting is not that great, it’s like… So lighting is key. And especially with Unreal Five, we have now, access to Lumen. It brought so much richness to the color, how the color is balancing with the entirety of the level. It definitely changed the way we were looking at the game.

We’re using the technology, but in a way to create something that feels like if you were looking at a painting. I think we have achieved that goal.

Chafe: I’m very happy with it.

IGN: What were your inspirations from other games or other media when developing the art style?

Primeau: I have many. I’ll start with graphic novels, European graphic novels. I really wanted to stay away from DC comics, Marvels comics, those kinds of classics.

Before I started Eternal Strand, I saw a video. It was one of the League of Legends short films for a competition. It’s “RISE.” I don’t know if you remember that one, but it was made by Fortiche Studio who did Arcane, and I’m a huge fan of Arcane. When I saw that short film, it was way before Arcane was announced, I was like, “oh gosh, this is freaking cool. This is so amazing. I wish I would be able to work on a game that has that kind of look.”

Chafe: For me, when we started the project, one of the things that I wanted to challenge myself a lot was in concept and drawing and stuff like that and doing more, learning more about color as well, which is something I find super fascinating and also kicks my butt all the time because of just color theory in general.

But with the [character] portraits specifically, I think, I mean, growing up I played a lot of games, a lot of JRPGs too. I played just seeing basic portraits in something like Golden Sun or eventually also Persona and of course Hades, which is a fantastic game. I played way too much of that, early access included. But I really liked that part. Visual novels too, just that kind of thing. You can get an emotion from a 2D image as well when it’s well done, especially if you have voices on top of it.

IGN: Were there any really influential pieces of concept art that served as a guiding document the team would reference later on?

Chafe: I have one personal: It’s really Maxime Desmettre’s stuff because it was so saturated. Blue, blue, blue sky. Maxim Desmettre is our concept artist that we have who works from Korea. When I joined the project, seeing that was just like… and seeing that as a challenge too, like ‘how are we going to get there?’

The one that I’m thinking of that hopefully we could find after, just in general with the work that always speaks so much to me is this blue, blue sky and the saturation of the grass. But also when he gets into his architecture and stuff like that, there’s just a warmth to everything. The warmth to the stone that just makes it look inviting and mysterious at the same time. And I think that really speaks a lot to it.

IGN: How did you go about designing Eternal Strand’s protagonist: Brynn?

Primeau: I think that Mike also, when he pitched me the character, he was using Indiana Jones as an example. So courageous, adventurer guy, cool guy. Also, when you’re looking at Indiana Jones, he’s a cool guy. And we wanted to create that kind of coolness also out of our main protagonist. And I remember it took time. We did many iterations.

Chafe: It was a lot of iterations for sure. Well, I think I had done a bunch of sketches because it’s what’s going to be the face of the player, and also to have her own personality as well in the story, and her history as well. And the mantle was a really big one too. What gives her one of sets of her powers and stuff, figuring that out was actually one of the longest processes. It’s just a cape, but at the same time, it’s getting that to work with gameplay and all that kind of stuff. But yeah, all of Brynn’s personality and her vibe really comes from a lot of good work from the narrative team. So, mostly collaboration there.

IGN: What’s the deal with Brynn’s mentor: Oria? How did you settle on a giant bird?

Chafe: Populating the world of the enclave was, “it’s free real estate.” You get to just throw things on the wall and see what sticks. And, “Oh, that’s really cool. Oh, that’s nice.” At some point I’d done a big sketch of a big bird lady with a claymore, and Seb said, “That’s cool.” And then kind of ran with it.

IGN: What’s the toughest part about the art style you’ve chosen for Eternal Strands?

Primeau: The toughest part was…A lot of people in the team have experience making games, so it was to get outside of that mold that we’ve been to.

For me, working on games that were more realistic in terms of look, I think it was really tough just to think differently, to change our mindset, especially that we knew that we would be a small team, so we had to do the art differently, find recipes, especially when we were talking about textures, for example. So having a good mix.

Chafe: One of the things too is also as we’re all a bunch of artists, and every artist has their own style that they just suddenly have ingrained in them, and that’s what makes us all unique as artists as well. But when you’re on a project, you have to coalesce together. You can’t kind of have one look different from the other. When you’re doing something more realistic, you have your North Star, which is a giant load of references that are real. And you can say “it has to look like that, as close to that as possible.”

When you have a style in mind and you’re developing at the same time, you kind of look at it and you review it and you have a feeling more than anything else.

You’re training each other with your styles as you kind of merge together in the end. And that kind of is how the style happened through, like you mentioned, like finding easy recipes, through just actually creating assets and seeing what comes out and, “Oh, that’s really cool. Okay, we can now use that as kind of our North Star.”

For more on Eternal Strands, check out our preview of the Ark of the Forge boss fight, or read our interview with the founders of Yellow Brick Games on going from AAA studios to their own indie shop, and for everything else stick with IGN.

Art

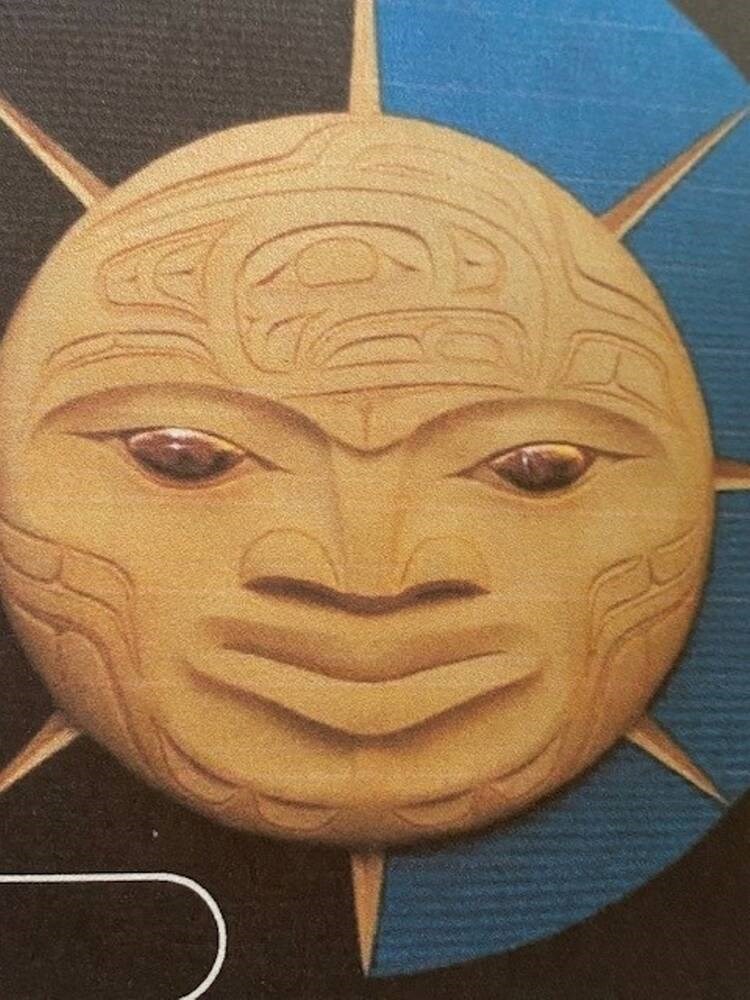

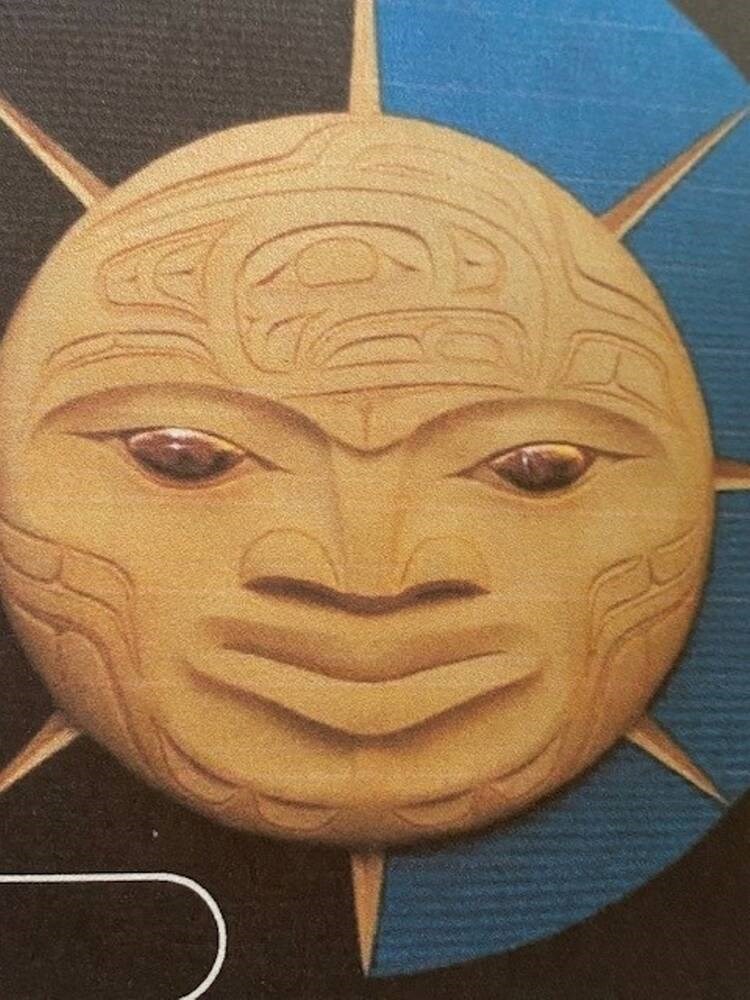

Collection of First Nations art stolen from Gordon Head home – Times Colonist

Saanich police are investigating the theft of a large collection of First Nations art valued at more than $60,000 from a Gordon Head home.

The theft happened on April 2.

The collection includes several pieces by Whitehorse-based artist Calvin Morberg, as well as Inuit carvings estimated to be more than 60 years old.

Anyone with information on the thef is asked to call Saanich police at 250-472-4321.

jbell@timescolonist.com

-

Tech11 hours ago

Tech11 hours agoSave $700 Off This 4K Projector at Amazon While You Still Can – CNET

-

Investment11 hours ago

Investment11 hours agoUK Mulls New Curbs on Outbound Investment Over Security Risks – BNN Bloomberg

-

Science11 hours ago

Science11 hours agoJeremy Hansen – The Canadian Encyclopedia

-

Tech10 hours ago

Tech10 hours ago'Kingdom Come: Deliverance II' Revealed In Epic New Trailer And It Looks Incredible – Forbes

-

Sports9 hours ago

Sports9 hours agoAuston Matthews denied 70th goal as depleted Leafs lose last regular-season game – Toronto Sun

-

Business8 hours ago

BC short-term rental rules take effect May 1 – CityNews Vancouver

-

Investment8 hours ago

Investment8 hours agoBenjamin Bergen: Why would anyone invest in Canada now? – National Post

-

Art8 hours ago

Collection of First Nations art stolen from Gordon Head home – Times Colonist