–>

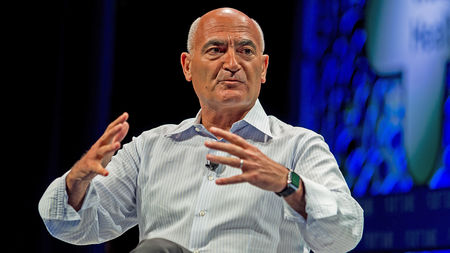

Moncef Saloui, the scientific head of Operation Warp Speed, spent 29 years making vaccines at GlaxoSmithKline.

Stuart Isett CC 2.0

Science‘s COVID-19 reporting is supported by the Pulitzer Center and the Heising-Simons Foundation.

On a nice day in early May, Moncef Slaoui was sitting by his pool when he received a phone call that would dramatically change his life—converting him from a retired executive of a big pharmaceutical company to the scientific leader of the Trump administration’s Operation Warp Speed, a multibillion-dollar crash program to develop a vaccine in record time.

What do you think about staging a Manhattan Project to make a COVID-19 vaccine? asked the caller, a person Slaoui would only describe to ScienceInsider as a former congressman who once headed the Biotechnology Innovation Organization, biotech’s powerful trade group. (James Greenwood is the only person with that resume.) Could we make a vaccine in 10, eight, or even 6 months or is it impossible? the caller pressed him. Slaoui, an immunologist who formerly headed vaccine development at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), gladly shared his thoughts. “I’m very passionate about preventing pandemics,” says Slaoui, who led a failed attempt to build a biopreparedness organization that explicitly aimed to rapidly make vaccines against emerging pathogens like SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Related

At the end of the call, the former congressman told Slaoui not to be surprised if somebody calls from the Trump administration. “Honestly, I hung up and told my wife, ‘Oh shit,’” Slaoui says. “I was hesitant around the politics.”

About 1.5 weeks later, a “senior leader” from the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) phoned and asked Slaoui to come to Washington, D.C. He made the trip from his home in Pennsylvania, meeting with the secretaries of HHS and defense, senior presidential adviser (and son-in-law) Jared Kushner, and a few others. “My No. 1 question was, ‘Is this going to be interfered with?’” Slaoui says. “Is this empowered 100%?” He says he got the answer he needed, and 4 days later, on 15 May he stood in the Rose Garden with President Donald Trump, who announced Slaoui as the scientific head of Operation Warp Speed.

To date, Warp Speed has invested more than $10 billion in eight vaccine candidates. Much of that money goes to “at-risk” purchasing of vaccines, which means the companies will produce hundreds of millions of doses that may wind up in the garbage if those candidates do not prove safe and effective. Three of the vaccines now are in large-scale efficacy trials, and interim looks at their data by independent safety and monitoring boards could reveal efficacy signals as early as October. If that happens, a vaccine could become quickly available through what’s known as an emergency use authorization (EUA), a regulatory pathway that the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has for diagnostics, treatments, and vaccines.

Talking to ScienceInsider today, Slaoui insisted he won’t be swayed by political pressures to rush an unsafe or ineffective vaccine, and that science will carry the day—or he’ll quit.

Slaoui has given few interviews since taking the Warp Speed job and he has taken something of a beating in the media for his financial holdings in companies working on COVID-19 vaccines—he was on the board of Moderna and has since stepped down, but he retains his GSK stock. And Warp Speed has been slammed for a lack of transparency on its decisions.

Slaoui spoke with ScienceInsider today for 25 minutes about his role, the challenges of the job, and the growing fear that politics and the upcoming elections on 3 November might influence the vaccine approval process. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Q: As the head of Operation Warp Speed, what do you actually do?

A: In partnership with General [Gustave] Perna, who is the chief operating officer and the ultimate decision-maker—I’m not a federal employee—we put together the overall plan. We said we want to build a portfolio of vaccines in order to manage the risk and also increase the chances that we have many vaccine doses. We said we need to use different platform technologies, all of which have to be very fast, that have different characteristics so we can reduce the risk of complete failure and also increase the opportunity to have vaccines for different subpopulations. Once we set that strategy, we started to operationalize it. Surprises come every day. New questions from the FDA. Or a clinical trial site that’s not recruiting. Or imbalances in the kind of populations that we want to have in the study. Or changing the geographic location of the sites because the epidemiology is evolving. There are 25 different sites in the U.S involved in the manufacturing of these six vaccines and General Perna and myself tour all of them. Frankly, it’s actually working even better than I was hoping.

Q: You have EUAs for hydroxychloroquine and convalescent plasma that were heavily criticized as having come about because of political pressure. Does that have blowback on you and the confidence in any vaccine EUA? Are you concerned that vaccine hesitancy is going to be fueled by the president overstating the promise of hydroxychloroquine and then convalescent plasma, which he called a historic breakthrough?

A: The science is what is going to guide us. And the science is what our team is focused on and will be judged by. And at the end of the day, the facts and the data will be made available to everyone who wants to look at them and will be transparent. I am confident that it will be a completely different scenario. We’re running phase III trials with 30,000 subjects—that’s much larger than for many vaccines that have been approved in the United States under a BLA [a biologics license application is FDA’s full approval process for a vaccine]. If a vaccine is efficacious, an EUA will require that the documentation and demonstration of efficacy be flawless. The long-term evidence of safety is going to be limited because these vaccines are going to have only 6 months or 5 months of data. So, we’re working superhard on a very active pharmacovigilance system, to make sure that when the vaccines are introduced that we’ll absolutely continue to assess their safety. Our intent is to drive the companies to a BLA that should be filed one, two, 3 months from an emergency use designation.

Q: Have you discussed with the administration the possibility of saying, ‘Let’s not ask for an EUA until after 3 November?’ Let’s just clear that off the deck right now, because there’s so much worry of an October surprise and something being pushed before 3 November. It’s not going to make a difference to the pandemic if there’s a vaccine on 2 November or 4 November.

A: I have to say, maybe even despite my personal political views, that I don’t think that’s right, because 1000 people die every day [from COVID-19]. If a vaccine [had evidence of safety and efficacy] on 25 October, it should be [requested] on 25 October. If it’s 17 November, it should be 17 November. If it’s 31 December, it should be 31 December.

It needs to be absolutely shielded from the politics. I cannot control what people say. The president says things, other people will say things Trust me, there will be no EUA filed if it’s not right.

Q: China has three vaccines in efficacy trials that use the whole virus and inactivate it. You don’t have a whole virus, inactivated vaccine in your portfolio. You’re sticking to the viral spike protein being engineered in different ways. You’re leaving an egg out of the basket for political reasons. Why don’t you have an inactivated vaccine in the portfolio?

A: I really don’t think an inactivated vaccine is a good idea. There are very strict scientific reasons. In the early 1960s, an inactivated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine was given and it enhanced disease. The second reason is I think there is a biosafety issue with 20,000-liter fermenters having trillions of virus particles and then inactivating them. Technology in today’s world allows us to not have to take those kinds of risks. If I was in the company I was in before, I’d make exactly the same decision.

Q: You’re an internationalist. You’re from Morocco, you’ve lived in Europe much of your life, you’ve had great concern about global equity throughout your career. Operation Warp Speed has said from the outset that it will not consider China-made vaccines. What happens if China has efficacy data and good safety data that are reasonable, and has a vaccine it’s going to approve? What do we do? Do we have any access to that vaccine? Or do we just wait?

A: I think it’s great if this would be the first demonstration that vaccines can work. That’s great news for the world. And frankly, if China had billions of doses of vaccine after serving its population, we would take it. We are fortunate. I believe we will have vaccines and may not be in that position. I heard the president, which was important to me, saying that if we produce enough vaccine to serve the United States, it will be available to others, including China.

Q: But the United States has not joined COVAX, an international financing mechanism to help assure that low- and middle-income countries have prompt access to any vaccines that prove safe and effective. I know you well enough that you would have voted to join COVAX. Personally, if it was your choice, wouldn’t you have?

A: I would, I would.

Q: You also have a history of being politically active. As a university student in Belgium, you were politically active. It’s in your blood: Your father, who resisted the French occupation of Morocco, was politically active. For you to now say there’s nothing political about Operation Warp Speed? Politics is all over this. And I wonder how you deal with political decisions that you disagree with.

A: I would immediately resign if there is undue interference in this process.

Q: If you see an EUA push you don’t believe in, you’re out?

A: I’m out. I have to say there has been absolutely no interference. Despite my past, which is still my present, I am still the same person with the same values. The pandemic is much bigger than that. Before being a political person with convictions, humanity has always been my objective.

Q: The monkey model data initially were going to be used as criteria for vaccine-candidate selection for Warp Speed. But it seems to me now that it’s almost, ‘Well, everything kind of works in monkeys. And nothing has a really serious safety signal.’ How are you using the monkey model to make decisions, or is it just there as a failsafe?

A: It’s a piece of the puzzle. If we did a monkey challenge and it didn’t work or it showed enhanced disease, we’d stop. But that hasn’t happened.

Q: There’s been a lot of handwringing about the fact that several of the vaccines Warp Speed is backing must be kept at extremely low temperatures before being used. Is the cold chain a problem?

A: It’s a challenge. One of the vaccines requires –80°C and two vaccines require –20°C. I think all the companies whose vaccines need –20°C or –80°C are working very hard and are set to have formulations that will be stable.

Q: You’ve been involved in many vaccine efforts: HIV, malaria, human papillomavirus. You worked on vaccines that didn’t even succeed. On the spectrum here, does SARS-CoV-2 look like it’s easy to beat, middle, or difficult?

A: This one has benefited from many things. One is the advance of platform technologies in vaccinology, particularly over the past 10 years. The second thing it has really benefited from is SARS and MERS [two respiratory diseases causes by coronaviruses related to SARS-CoV-2]. Vaccines were designed for those. So, knowing how to how to construct the [structure] of the spike was super important. From that perspective, it’s easier because past experience has been extremely relevant to this.

From the perspective of how to design the trials, how to manufacture [the vaccines], how to find the endpoints of the study based on disease, how to optimize for the epidemiology, clinical trial sites, and things like that, we haven’t yet hit the wall. One of the reasons we said we needed six or eight vaccines is because some of them may or will hit the wall.

Source: – Science Magazine