The setting sun backlights a pristine panoply of pines of different sizes and species. Far northern Canadian countryside rolls by at a leisurely pace of a train ride, viewed through an upper deck glass-enclosed of a special observation car. Waves of green and brown in slightly varying shades sweep by. There’s no working Wi-Fi to interrupt with emails or social media demanding attention.

It’s mesmerizing and calming. Two or three hours pass peacefully without notice.

Now repeat. Repeat again. And again. Two hours becomes two days.

To get between Churchill, Manitoba, Canada — the polar bear and beluga whale capital of the world and a tourist hot spot for northern adventure tourism — and Winnipeg, Manitoba, there are only two options: A $1,100 one-way plane flight that takes two-and-a-half hours or a scenic 45-hour to 49-hour much cheaper train ride. It’s a $200 train ride like few others from the glass ceiling of the observation car Canada’s VIA railroad bills it as a “scenic adventure.”

It starts with a vista of the tree-less but not quite barren tundra, then powers through hours of tall forests. They eventually give way to more manicured cropland with the occasional animal, even a herd of elk. Sunset glimmers off a lake. When night comes it holds the hope of a Northern Lights sighting stretching all around. If there are no glimmering auroras, there’s a special beauty in the pitch black outside with only the lights of the train interrupting.

And it goes on for 1,697 kilometers (1,054 miles). There are 10 listed stops enroute with some only for a few minutes and others a few hours.

It’s Churchill’s connection to the rest of the world

While it’s promoted for tourism, the train is actually a lifeline for the town of Churchill. The community has roads inside town and for a few miles to the outskirts, but no roads go to other cities. So it’s expensive flying or an overnight train ride at a more reasonable price tag.

The semi-weekly trains bring tourists, residents, mail, food, fuel and other necessities.

From May 2017 to October 2018, part of the rail line washed out because of storms and poor maintenance, stranding an entire community.

Staples had to be delivered by air and propane fuel was brought in by ship through the Hudson Bay. Prices in town skyrocketed and lawsuits were filed over who was responsible for the repair costs.

“We had no rail service for about 18 months meaning Churchilleans couldn’t go out by rail to visit their families in other parts of Manitoba,” Churchill Mayor Mike Spence said. “It was devastating.”

The town and some First Nations in the area took over the rail line and it’s back to operating. Spence said with the community pouring tens of millions of dollars into repairs the lines should stay open even as the world’s weather gets more extreme.

It’s a very long ride

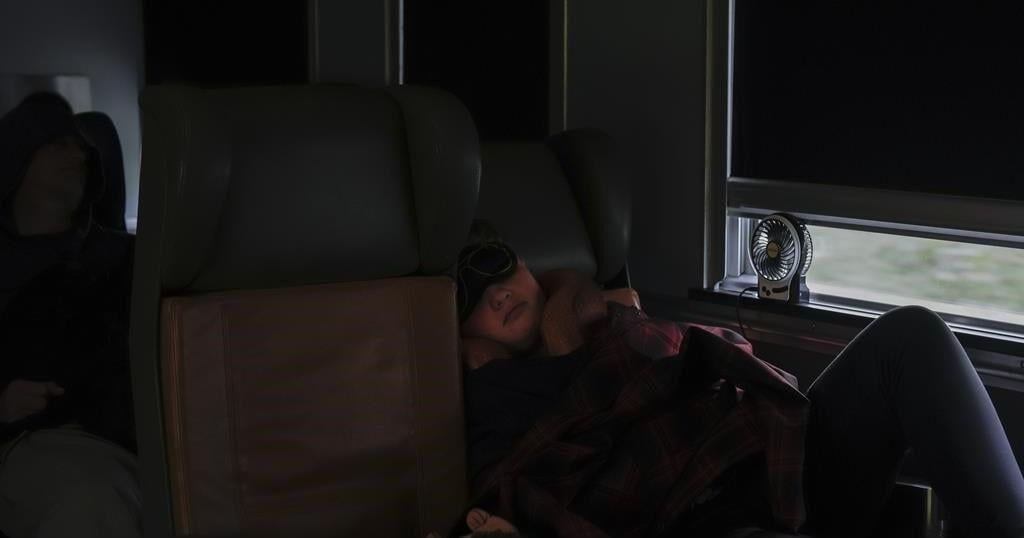

Sleeper berths are available on the train, along with shower cubicles the size of those in a New York hotel room, but for those traveling more cheaply or booking late, there are standard seats in the cabin. The seats recline — mostly. But it’s not full laying down.

Food is also limited.

There is a small galley below the observation deck. It has some food, heated by a microwave. The train does serve beer, but limited brands. Frequent commuters and those who do their research know to bring their own snacks on board, and make the most of the restaurants at longer stops in towns on route.

Stations along the way vary greatly: In Dauphin, passengers wait outside an historic brick station built in 1912, but in Wabowden, a single yellow sign nailed to a pole near the track that reads “Muster Point” alerts passengers to the stop.

For residents of smaller communities along the route, the train provides the only connection to other parts of Manitoba.

At Thompson, passengers are better connected — and fed

Many ride the train weekly, traveling to and from Thompson. At about 13,600 residents, it’s the biggest community the train stops at, besides Winnipeg, with amenities like big-box stores and restaurants.

Thompson — just under halfway between Churchill and Winnipeg — is where many Churchill residents train journey ends.

Residents said they often keep cars in Thompson, take the train there and then drive to Winnipeg. They can shave 17 hours off the trip that way, they said.

All but two dozen passengers got off at Thompson, the closest bigger community connected to the rest of Manitoba by road.

First Nation communities line the route

After leaving Thompson, the train heads to remote First Nation communities on both sides of the route.

And though the journey distance-wise is short, it takes hours by train, with many passengers passing the time playing cards and chatting with each other in the dining car.

The town of Pas, a longer stop on the route, includes a bar right by the station. But the train’s porter warned passengers off it, saying it was a rather rough establishment. She knew because she has been there.

In Thicket Portage, population around 150, residents gather to meet their rides back to town at the stop, a small wooden shack near the tracks. Here, they unload their luggage and other goods, food, diapers and other staples.

The train also ventured into a different zone in eastern Saskatchewan and the cute downtown of Canora, which strangely wasn’t on the train schedule for stops.

As the train heads further south, the landscape changes, the northern forest giving way to crop fields and livestock as the route approaches Winnipeg in southern Manitoba.

And finally, after 49 hours, the train pulls into Winnipeg.

This glimpse into the beautiful monotony of vast stretches of untouched trees and tan tundra is a trip of a lifetime, which — for some passengers at least — seemed to last that long.

___

Read more of AP’s climate coverage at http://www.apnews.com/climate-and-environment

___

Follow Seth Borenstein and Joshua Bickel on X at @borenbears and @Joshuabickel

______

The Associated Press’ climate and environmental coverage receives financial support from multiple private foundations. AP is solely responsible for all content. Find AP’s standards for working with philanthropies, a list of supporters and funded coverage areas at AP.org.