Health

My third COVID-19 infection: Why reinfection can be anything but mild

|

|

As the pandemic approaches its third anniversary, most people are well and truly bored with COVID-19. With so many of us having recovered from at least one COVID-19 infection, not to mention being vaccinated and/or boosted, it is seductive to believe that catching it again won’t matter.

I’ve been to pubs and parties, packed myself onto public transport without a facemask, and entertained various guests with ‘colds’. But having just experienced COVID for the third time, I am regretting letting my guard down.

This is particularly true in the Omicron era, where we’re encouraged to believe that COVID-19 is ‘nothing but a minor sniffle’ and we must ‘learn to live with the virus’. I too have been enjoying largely living life as if the pandemic never happened in recent weeks and months. I’ve been to pubs and parties, packed myself onto public transport without a facemask, and entertained various guests with ‘colds’. But having just experienced COVID for the third time, I am regretting letting my guard down.

I am not advocating a return to full or even partial lockdowns; I desperately want my kids to continue attending school, and I don’t think pubs or restaurants need to stop serving customers indoors either. But as evidence mounts that northern hemisphere countries could experience a new wave of COVID-19 infections as winter approaches, combined with the return of influenza and other everyday illnesses, the onus is on everyone to do what they can to keep themselves – and each other – healthy.

COVID-19 reinfection

This latest bout of COVID-19, was my third in less than three years. The first, in March 2020, was characterised by a persistent cough and chest pains; the second, in June 2021, by fatigue and loss of taste and smell (I still suffer from “parosmia”). Having recovered from these infections, and been vaccinated, and boosted – twice – I had assumed that were I to catch it again, any illness would be negligible.

Ever since the rise of Omicron, scientists have talked about its relative mildness – particularly in healthy people who have been vaccinated, like me. But my third experience of COVID-19 has been my worst yet.

Part of the problem, I think, is that the medical description of “mild illness” is at odds with the normal perception of “mild”, such as with mild weather or mild cheese. When doctors and scientists talk about “mild COVID-19”, what they mean is “not severe enough to cause breathing difficulties”.

This time, I experienced various “cold-like” symptoms – sore throat, sneezing, runny nose – but it was the feverishness and headaches that immobilised me in bed for three days, unable to cook, do anything for my kids, or work. Fortunately, I am gradually starting to feel better, but my experience of “mild COVID” was easily on par with flu – an illness I previously vowed never to catch again. The possibility of going through it all again next year, assuming that’s what ‘living with coronavirus’ means, is already filling me with dread.

Waning immunity

Whereas at the start of the pandemic, nobody had any immunity to SARS-CoV-2, nearly three years on, everyone’s immune systems are on a slightly different learning curve.

Unfortunately, current COVID-19 vaccines still only top-up people’s immune protection for a limited period before their antibody levels begin to drop. They will still be largely protected against severe disease and death, but waning antibodies increase individuals’ susceptibility to reinfection.

Although at the extreme end of the spectrum, reinfections tend to be less severe than people’s first brush with SARS-CoV-2, data from the UK’s Office for National Statistics have suggested that the proportion of people reporting symptoms during reinfection varies according to which variants they have been infected with before. When they were infected, relative to their last COVID-19 infection or vaccination, could also influence their symptom severity, because levels of protective antibodies gradually diminish over time.

Then there’s how much virus someone is exposed to. According to Ben Krishna, a postdoctoral researcher in immunology and virology at the University of Cambridge, UK, infection with a higher dose of virus (say, if someone with COVID-19 sneezes in your face) could enable higher levels of virus to gain a foothold in the body before the immune system manages to stamp them out, resulting in more severe symptoms.

Have you read?

Booster campaign

My last COVID-19 booster was in June, so I was surprised to have come down with it again so soon. My experience shows that boosters do not offer total protection from the disease even though they are very effective in preventing severe disease and death. COVID-19 vaccines have had a massive impact on people’s risk of being hospitalised with or dying from the disease, and are the reason many countries have largely been able to return to normal life, without hospitals being overwhelmed.

Unfortunately, current COVID-19 vaccines still only top-up people’s immune protection for a limited period before their antibody levels begin to drop. They will still be largely protected against severe disease and death, but waning antibodies increase individuals’ susceptibility to reinfection.

Unlike the COVID-19 waves we experienced during 2020 and 2021, where a single variant, such as Delta, rapidly outcompeted all others and spread across the world, virologists are currently tracking the growth of multiple subvariants

The rationale for some countries launching COVID-19 booster campaigns in the coming weeks and months is to temporarily boost antibodies, reducing the risk of a sharp increase in severe cases, precisely when hospitals are likely to be grappling with a spike in influenza admissions. It is therefore important to take up the offer of a booster vaccine, if you are offered one, but it won’t make you invincible.

Viral evolution

Then there’s the issue of increasingly immune-resistant subvariants. Although the WHO hasn’t assigned any new Greek letters since Omicron, the subvariant that’s making me sick is likely very different to the one that infected my husband in early March, which was itself quite different to the original BA.1 version of Omicron that emerged in November 2021. The number of new, and potentially worrying Omicron subvariants in circulation right now, is unprecedented.

Unlike the COVID-19 waves we experienced during 2020 and 2021, where a single variant, such as Delta, rapidly outcompeted all others and spread across the world, virologists are currently tracking the growth of multiple subvariants, each carrying overlapping changes to the spike protein, which SARS-CoV-2 uses to grab onto, and infect human cells. Crucially, these mutations affect the ability of antibodies to recognise the virus and block it from infecting us.

If you are unfortunate enough to be reinfected, it is still likely that your infection will be mild. But mild doesn’t necessarily mean trivial. Not everyone has the benefit of sick pay, or a partner who can take over all childcare duties while their other half quarantines in bed.

Although vaccination and previous COVID infections have left us with other weapons against the virus, its ongoing evolution and individuals’ waning immunity means that even people who caught COVID-19 in May or June, when the BA.4 and BA.5 Omicron subvariants took off, could be susceptible to reinfection with the newest crop of subvariants, assuming they continue to spread.

Disruptive illness

If you are unfortunate enough to be reinfected, it is still likely that your infection will be mild. But mild doesn’t necessarily mean trivial. Not everyone has the benefit of sick pay, or a partner who can take over all childcare duties while their other half quarantines in bed. Even for those lucky enough to have these things, the risk of Long COVID still looms large.

COVID-19 isn’t just about individual risk. There are still plenty of people in our communities who risk being hospitalised, or developing lasting disability, if they catch COVID-19 – even if they’ve been vaccinated. This includes people who may look relatively young and healthy. Living life as if there’s no pandemic is risky – for everyone.

It is also unsustainable. Widespread absences due to COVID-19, flu, or any other infection, risks there being too few teachers, delivery drivers, healthcare staff and other essential workers to keep society running as normal.

Everyone wishes for a return to normal life, but behaving as if there is no COVID-19 will have consequences. Relative normality is another matter. With a few common-sense precautions – such as avoiding mixing with people if you are unwell; wearing a good quality facemask in crowded indoor spaces if local case numbers are high (particularly if you are unwell); taking a COVID-19 test if you can; getting a booster vaccine if you are offered one; and keeping indoor spaces ventilated – we can all help to keep everyone protected.

Health

Cancer Awareness Month – Métis Nation of Alberta

Cancer Awareness Month

Posted on: Apr 18, 2024

April is Cancer Awareness Month

As we recognize Cancer Awareness Month, we stand together to raise awareness, support those affected, advocate for prevention, early detection, and continued research towards a cure. Cancer is the leading cause of death for Métis women and the second leading cause of death for Métis men. The Otipemisiwak Métis Government of the Métis Nation Within Alberta is working hard to ensure that available supports for Métis Citizens battling cancer are culturally appropriate, comprehensive, and accessible by Métis Albertans at all stages of their cancer journey.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis, whether for yourself or a loved one, can feel overwhelming, leaving you unsure of where to turn for support. In June, our government will be launching the Cancer Supports and Navigation Program which will further support Métis Albertans and their families experiencing cancer by connecting them to OMG-specific cancer resources, external resources, and providing navigation support through the health care system. This program will also include Métis-specific peer support groups for those affected by cancer.

With funding from the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC) we have also developed the Métis Cancer Care Course to ensure that Métis Albertans have access to culturally safe and appropriate cancer services. This course is available to cancer care professionals across the country and provides an overview of who Métis people are, our culture, our approaches to health and wellbeing, our experiences with cancer care, and our cancer journey.

Together, we can make a difference in the fight against cancer and ensure equitable access to culturally safe and appropriate care for all Métis Albertans. Please click on the links below to learn more about the supports available for Métis Albertans, including our Compassionate Care: Cancer Transportation program.

I wish you all good health and happiness!

Bobbi Paul-Alook

Secretary of Health & Seniors

Health

Type 2 diabetes is not one-size-fits-all: Subtypes affect complications and treatment options – The Conversation

You may have heard of Ozempic, the “miracle drug” for weight loss, but did you know that it was actually designed as a new treatment to manage diabetes? In Canada, diabetes affects approximately 10 per cent of the general population. Of those cases, 90 per cent have Type 2 diabetes.

This metabolic disorder is characterized by persistent high blood sugar levels, which can be accompanied by secondary health challenges, including a higher risk of stroke and kidney disease.

Locks and keys

In Type 2 diabetes, the body struggles to maintain blood sugar levels in an acceptable range. Every cell in the body needs sugar as an energy source, but too much sugar can be toxic to cells. This equilibrium needs to be tightly controlled and is regulated by a lock and key system.

In the body’s attempt to manage blood sugar levels and ensure that cells receive the right amount of energy, the pancreatic hormone, insulin, functions like a key. Cells cover themselves with locks that respond perfectly to insulin keys to facilitate the entry of sugar into cells.

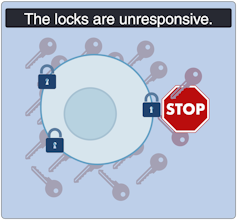

Unfortunately, this lock and key system doesn’t always perform as expected. The body can encounter difficulties producing an adequate number of insulin keys, and/or the locks can become stubborn and unresponsive to insulin.

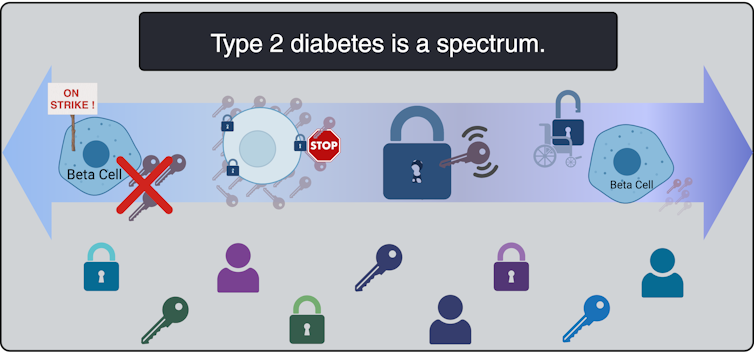

All forms of diabetes share the challenge of high blood sugar levels; however, diabetes is not a singular condition; it exists as a spectrum. Although diabetes is broadly categorized into two main types, Type 1 and Type 2, each presents a diversity of subtypes, especially Type 2 diabetes.

These subtypes carry their own characteristics and risks, and do not respond uniformly to the same treatments.

To better serve people living with Type 2 diabetes, and to move away from a “one size fits all” approach, it is beneficial to understand which subtype of Type 2 diabetes a person lives with. When someone needs a blood transfusion, the medical team needs to know the patient’s blood type. It should be the same for diabetes so a tailored and effective game plan can be implemented.

This article explores four unique subtypes of Type 2 diabetes, shedding light on their causes, complications and some of their specific treatment avenues.

Severe insulin-deficient diabetes: We’re missing keys!

(Lili Grieco-St-Pierre, Jennifer Bruin/Created with BioRender.com)

Insulin is produced by beta cells, which are found in the pancreas. In the severe insulin-deficient diabetes (SIDD) subtype, the key factories — the beta cells — are on strike. Ultimately, there are fewer keys in the body to unlock the cells and allow entry of sugar from the blood.

SIDD primarily affects younger, leaner individuals, and unfortunately, increases the risk of eye disease and blindness, among other complications. Why the beta cells go on strike remains largely unknown, but since there is an insulin deficiency, treatment often involves insulin injections.

Severe insulin-resistant diabetes: But it’s always locked!

(Lili Grieco-St-Pierre, Jennifer Bruin/Created with BioRender.com)

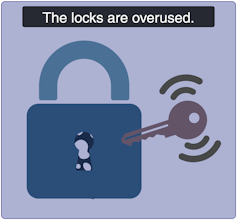

In the severe insulin-resistant diabetes (SIRD) subtype, the locks are overstimulated and start ignoring the keys. As a result, the beta cells produce even more keys to compensate. This can be measured as high levels of insulin in the blood, also known as hyperinsulinemia.

This resistance to insulin is particularly prominent in individuals with higher body weight. Patients with SIRD have an increased risk of complications such as fatty liver disease. There are many treatment avenues for these patients but no consensus about the optimal approach; patients often require high doses of insulin.

Mild obesity-related diabetes: The locks are sticky!

(Lili Grieco-St-Pierre, Jennifer Bruin/Created with BioRender.com)

Mild obesity-related (MOD) diabetes represents a nuanced aspect of Type 2 diabetes, often observed in individuals with higher body weight. Unlike more severe subtypes, MOD is characterized by a more measured response to insulin. The locks are “sticky,” so it is challenging for the key to click in place and open the lock. While MOD is connected to body weight, the comparatively less severe nature of MOD distinguishes it from other diabetes subtypes.

To minimize complications, treatment should include maintaining a healthy diet, managing body weight, and incorporating as much aerobic exercise as possible. This is where drugs like Ozempic can be prescribed to control the evolution of the disease, in part by managing body weight.

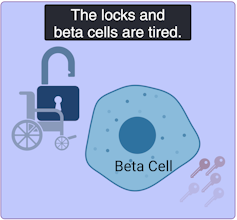

Mild age-related diabetes: I’m tired of controlling blood sugar!

(Lili Grieco-St-Pierre, Jennifer Bruin/Created with BioRender.com)

Mild age-related diabetes (MARD) happens more often in older people and typically starts later in life. With time, the key factory is not as productive, and the locks become stubborn. People with MARD find it tricky to manage their blood sugar, but it usually doesn’t lead to severe complications.

Among the different subtypes of diabetes, MARD is the most common.

Unique locks, varied keys

While efforts have been made to classify diabetes subtypes, new subtypes are still being identified, making proper clinical assessment and treatment plans challenging.

In Canada, unique cases of Type 2 diabetes were identified in Indigenous children from Northern Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario by Dr. Heather Dean and colleagues in the 1980s and 90s. Despite initial skepticism from the scientific community, which typically associated Type 2 diabetes with adults rather than children, clinical teams persisted in identifying this as a distinct subtype of Type 2 diabetes, called childhood-onset Type 2 diabetes.

Read more:

Indigenous community research partnerships can help address health inequities

Childhood-onset Type 2 diabetes is on the rise across Canada, but disproportionately affects Indigenous youth. It is undoubtedly linked to the intergenerational trauma associated with colonization in these communities. While many factors are likely involved, recent studies have discovered that exposure of a fetus to Type 2 diabetes during pregnancy increases the risk that the baby will develop diabetes later in life.

Acknowledging this distinct subtype of Type 2 diabetes in First Nations communities has led to the implementation of a community-based health action plan aimed at addressing the unique challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples. It is hoped that partnered research between communities and researchers will continue to help us understand childhood-onset Type 2 diabetes and how to effectively prevent and treat it.

A mosaic of conditions

(Lili Grieco-St-Pierre, Jennifer Bruin/Created with BioRender.com)

Type 2 diabetes is not uniform; it’s a mosaic of conditions, each with its own characteristics. Since diabetes presents so uniquely in every patient, even categorizing into subtypes does not guarantee how the disease will evolve. However, understanding these subtypes is a good starting point to help doctors create personalized plans for people living with the condition.

While Indigenous communities, lower-income households and individuals living with obesity already face a higher risk of developing Type 2 diabetes than the general population, tailored solutions may offer hope for better management. This emphasizes the urgent need for more precise assessments of diabetes subtypes to help customize therapeutic strategies and management strategies. This will improve care for all patients, including those from vulnerable and understudied populations.

Health

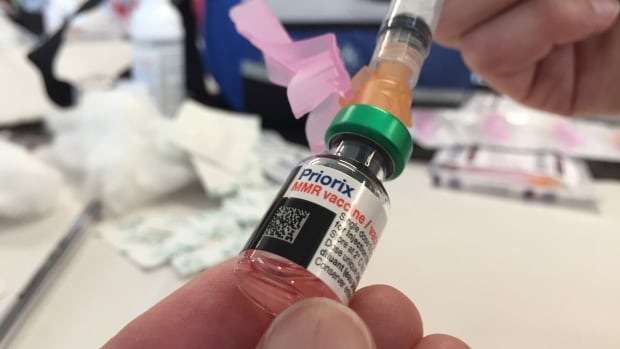

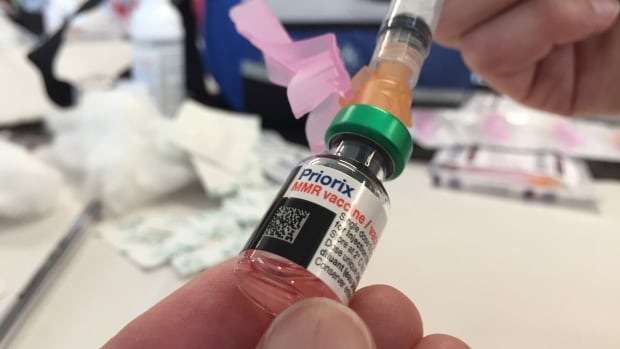

Quebec successfully pushes back against rise in measles cases – CBC.ca

Quebec appears to be winning its battle against the rising tide of measles after 45 cases were confirmed province-wide this year.

“We’ve had no locally transmitted measles cases since March 25, so that’s good news,” said Dr. Paul Le Guerrier, responsible for immunization for Montreal Public Health.

There are 17 patients with measles in Quebec currently, and the most recent case is somebody who was infected while abroad, he said.

But it was no small task to get to this point.

Le Guerrier said once local transmission was detected, news was spread fast among health centres to ensure proper protocols were followed — such as not letting potentially infected people sit in waiting rooms for hours on end.

Then about 90 staffers were put to work, tracking down those who were in contact with positive cases and are not properly vaccinated. They were given post-exposure prophylaxis, which prevents disease, said Le Guerrier.

From there, a vaccination campaign was launched, especially in daycares, schools and neighbourhoods with low inoculation rates. There was an effort to convince parents to get their children vaccinated.

Vaccination in schools boosted

Some schools, mostly in Montreal, had vaccination rates as low as 30 or 40 per cent.

“Vaccination was well accepted and parents responded well,” said Le Guerrier. “Some schools went from very low to as high as 85 to 90 per cent vaccination coverage.”

But it’s not only children who aren’t properly vaccinated. Le Guerrier said people need two doses after age one to be fully inoculated, and he encouraged people to check their status.

There are all kinds of reasons why people aren’t vaccinated, but it’s only about five per cent who are against immunization, he said. So far, some 10,000 people have been vaccinated against measles province-wide during this campaign, Le Guerrier said.

The next step is to continue pushing for further vaccination, but he said, small outbreaks are likely in the future as measles is spreading abroad and travellers are likely to bring it back with them.

Need to improve vaccination rate, expert says

Dr. Donald Vinh, an infectious diseases specialist from the McGill University Health Centre, said it’s not time to rest on our laurels, but this is a good indication that public health is able to take action quickly and that people are willing to listen to health recommendations.

“We are not seeing new cases or at least the new cases are not exceeding the number of cases that we can handle,” said Vinh.

“So these are all reassuring signs, but I don’t think it’s a sign that we need to become complacent.”

Vinh said there are also signs that the public is lagging in vaccine coverage and it’s important to respond to this with improved education and access. Otherwise, microbes capitalize on our weaknesses, he said.

Getting vaccination coverage up to an adequate level is necessary, Vinh said, or more small outbreaks like this will continue to happen.

“And it’s very possible that we may not be able to get one under control if we don’t react quickly enough,” he said.

-

Science8 hours ago

Science8 hours agoJeremy Hansen – The Canadian Encyclopedia

-

Tech7 hours ago

Tech7 hours agoSave $700 Off This 4K Projector at Amazon While You Still Can – CNET

-

Investment8 hours ago

Investment8 hours agoUK Mulls New Curbs on Outbound Investment Over Security Risks – BNN Bloomberg

-

Tech6 hours ago

Tech6 hours ago'Kingdom Come: Deliverance II' Revealed In Epic New Trailer And It Looks Incredible – Forbes

-

Sports6 hours ago

Sports6 hours agoAuston Matthews denied 70th goal as depleted Leafs lose last regular-season game – Toronto Sun

-

Health21 hours ago

Health21 hours agoSupervised consumption sites urgently needed, says study – Sudbury.com

-

Real eState7 hours ago

Sick of Your Blue State? These Real Estate Agents Have Just the Place for You. – The New York Times

-

Science21 hours ago

Science21 hours agoGiant, 82-foot lizard fish discovered on UK beach could be largest marine reptile ever found – Livescience.com