Science

NASA’s New Budget for Artemis? $28 Billion – Universe Today

It’s no exaggeration to say that NASA’s plans to return astronauts to the Moon has faced its share of challenges. From its inception, Project Artemis has set some ambitious goals, up to and including placing “the first woman and next man” on the Moon by 2024. Aside from all the technical challenges that this entails, there’s also the question of budgets. As the Apollo Era taught us, reaching the moon in a few years doesn’t come cheap!

Funding is an especially sticky issue right now because of the fact that we’re in an election year and NASA may be dealing with a new administration come Jan of 2021. In response, NASA announced a budget last week (Mon. Sept 21st) that put a price tag on returning astronauts to the Moon. According to NASA, it will cost taxpayers $28 billion between 2021 and 2025 to make sure Project Artemis’ meets its deadline of 2024.

On the same day during a phone briefing with journalists, NASA Administrator Jim Bridenstine noted that “political risks” are often the biggest obstacle to NASA’s work. This is perhaps a reference to the fact that NASA’s plans and goals have forcible shifted over the past decade or so in response to the changing priorities of new administrations.

When he took office in 2009, President Obama and his cabinet inherited the Constellation Program initiated by the Bush administration in 2005. This program aimed to create a new generation of launch systems and spacecraft to return astronauts to the Moon by 2020 at the latest. However, due to the then-current economic crisis and recommendations that the 2020 deadline could not be reached, it was canceled.

A year later, the Obama administration initiated NASA’s “Journey to Mars,” which picked up much of Constellation’s architecture but shifted the focus to a crewed mission to Mars by the 2030s. By 2017, VP Pence announced that the Trump administration’s focus would be on returning to the Moon within the 2020s. By March of 2019, Project Artemis was officially unveiled and NASA was charged with returning to the Moon in five years.

Approval for this funding now falls to Congress, which will be looking at elections by November 3rd. This year, in addition to deciding who will be president, 434 of the 435 Congressional districts across all 50 US states and 33 class 2 Senate seats will be contested. Come January, NASA could be dealing with an entirely new government.

According to Bridenstine, the first tranche of funding ($3.2 billion) must be approved by Christmas in order for NASA to remain “on track for a 2024 moon landing.” In total, NASA will require a full $16 billion in order to fund the development of the human landing system (HLS) – aka. a lunar lander – that will allow the crew of the Artemis III mission (one man and one woman) to land on the surface of the Moon.

At present, three major companies are competing to see which of their concepts NASA will choose. They include SpaceX, which presented NASA with a modified version of their Starship designed, altered to accommodate lunar landings. Then there’s Alabama-based Dynetics’ Human Landing System (DHLS), a vehicle that will provide both descent and ascent capabilities.

Rounding out the competitors is Blue Origin, meanwhile is collaborating on a design for an Integrated Lander Vehicle (ILV) that will consist of three elements – the descent, transfer, and ascent elements – designed by Blue Origin, Northrop Grumman, and Lockheed Martin, respectively. The winning design will either be integrated with the Orion capsule carrying the crew to the Moon or will launch on its own atop a company rocket.

Bridenstine also took the opportunity to set the record straight regarding where the Artemis III mission would be landing. This was in response to a previous statement he made during an online meeting of the Lunar Exploration Analysis Group (LEAG), which seemed to hint that the Artemis crews might revisit the Apollo sites.

“If you’re going to go to the equatorial region again, how are you going to learn the most?” he said. “You could argue that you’ll learn the most by going to the places where we put gear in the past. There could be scientific discoveries there and, of course, just the inspiration of going back to an original Apollo site would be pretty amazing as well.”

During Monday’s phone briefing, however, Bridenstine emphasized that the mission will be heading to the South Pole-Aitken Basin:

“To be clear, we’re going to the South Pole. There’s no discussion of anything other than that. The science that we would be doing is really very different than anything we’ve done before. We have to remember during the Apollo era, we thought the moon was bone dry. Now we know that there’s lots of water ice and we know that it’s at the South Pole.”

Investigations of this ice and other resources will be intrinsic to long-term plans to create the Artemis Base Camp. The current schedule has the Artemis I flight (which will be uncrewed) taking place by November of 2021. This will be the inaugural flight of NASA’s Space Launch System (SLS) flying with the Orion space capsule. Artemis II is scheduled for 2023, and will take a crew of astronauts around the Moon but will not attempt a lunar landing.

In 2024, the long-awaited Artemis III mission will occur and will see astronauts land on the surface for a week of operations and up to five operations on the surface. Beyond 2024, NASA plans to deploy the various segments that make up the Lunar Gateway, which will facilitate more long-term missions to the lunar surface and allow for the construction of the Artemis Base Camp.

Further Reading: Phys.org

Science

"Hi, It's Me": NASA's Voyager 1 Phones Home From 15 Billion Miles Away – NDTV

<!–

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 was mankind’s first spacecraft to enter the interstellar medium

Washington, United States:

NASA’s Voyager 1 probe — the most distant man-made object in the universe — is returning usable information to ground control following months of spouting gibberish, the US space agency announced Monday.

The spaceship stopped sending readable data back to Earth on November 14, 2023, even though controllers could tell it was still receiving their commands.

In March, teams working at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory discovered that a single malfunctioning chip was to blame, and devised a clever coding fix that worked within the tight memory constraints of its 46-year-old computer system.

window._rrCode = window._rrCode || [];_rrCode.push(function() (function(v,d,o,ai)ai=d.createElement(“script”);ai.defer=true;ai.async=true;ai.src=v.location.protocol+o;d.head.appendChild(ai);)(window, document, “//a.vdo.ai/core/v-ndtv/vdo.ai.js”); );

“Voyager 1 spacecraft is returning usable data about the health and status of its onboard engineering systems,” the agency said.

Hi, it’s me. – V1 https://t.co/jgGFBfxIOe

— NASA Voyager (@NASAVoyager) April 22, 2024

“The next step is to enable the spacecraft to begin returning science data again.”

Launched in 1977, Voyager 1 was mankind’s first spacecraft to enter the interstellar medium, in 2012, and is currently more than 15 billion miles from Earth. Messages sent from Earth take about 22.5 hours to reach the spacecraft.

Its twin, Voyager 2, also left the solar system in 2018.

Both Voyager spacecraft carry “Golden Records” — 12-inch, gold-plated copper disks intended to convey the story of our world to extraterrestrials.

These include a map of our solar system, a piece of uranium that serves as a radioactive clock allowing recipients to date the spaceship’s launch, and symbolic instructions that convey how to play the record.

The contents of the record, selected for NASA by a committee chaired by legendary astronomer Carl Sagan, include encoded images of life on Earth, as well as music and sounds that can be played using an included stylus.

window._rrCode = window._rrCode || [];_rrCode.push(function(){ (function(d,t) var s=d.createElement(t); var s1=d.createElement(t); if (d.getElementById(‘jsw-init’)) return; s.setAttribute(‘id’,’jsw-init’); s.setAttribute(‘src’,’https://www.jiosaavn.com/embed/_s/embed.js?ver=’+Date.now()); s.onload=function()document.getElementById(‘jads’).style.display=’block’;s1.appendChild(d.createTextNode(‘JioSaavnEmbedWidget.init(a:”1″, q:”1″, embed_src:”https://www.jiosaavn.com/embed/playlist/85481065″,”dfp_medium” : “1”,partner_id: “ndtv”);’));d.body.appendChild(s1);; if (document.readyState === ‘complete’) d.body.appendChild(s); else if (document.readyState === ‘loading’) var interval = setInterval(function() if(document.readyState === ‘complete’) d.body.appendChild(s); clearInterval(interval); , 100); else window.onload = function() d.body.appendChild(s); ; )(document,’script’); });

Their power banks are expected to be depleted sometime after 2025. They will then continue to wander the Milky Way, potentially for eternity, in silence.

(Except for the headline, this story has not been edited by NDTV staff and is published from a syndicated feed.)

Science

West Antarctica's ice sheet was smaller thousands of years ago – here's why this matters today – The Conversation

As the climate warms and Antarctica’s glaciers and ice sheets melt, the resulting rise in sea level has the potential to displace hundreds of millions of people around the world by the end of this century.

A key uncertainty in how much and how fast the seas will rise lies in whether currently “stable” parts of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet can become “unstable”.

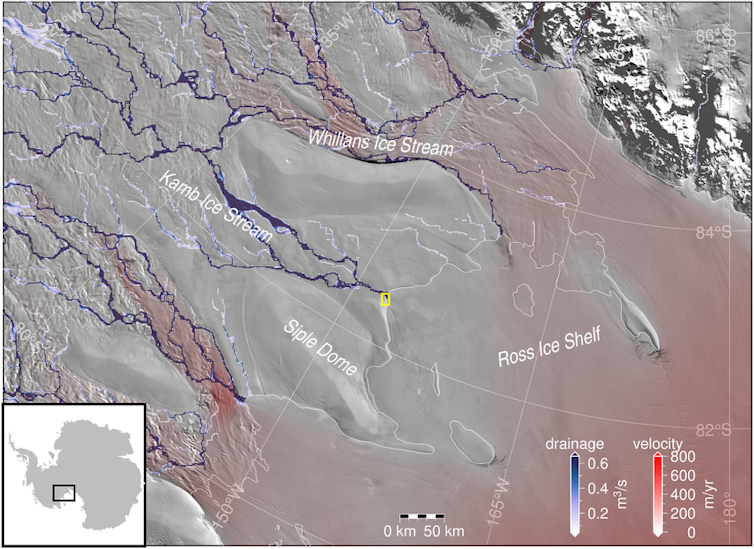

One such region is West Antarctica’s Siple Coast, where rivers of ice flow off the continent and drain into the ocean.

Journal of Geophysical Research, CC BY-SA

This ice flow is slowed down by the Ross Ice Shelf, a floating mass of ice nearly the size of Spain, which holds back the land-based ice. Compared to other ice shelves in West Antarctica, the Ross Ice Shelf has little melting at its base because the ocean below it is very cold.

Although this region has been stable during the past few decades, recent research suggest this was not always the case. Radiocarbon dating of sediments from beneath the ice sheet tells us that it retreated hundreds of kilometres some 7,000 years ago, and then advanced again to its present position within the last 2,000 years.

Figuring out why this happened can help us better predict how the ice sheet will change in the future. In our new research, we test two main hypotheses.

Read more:

What an ocean hidden under Antarctic ice reveals about our planet’s future climate

Testing scenarios

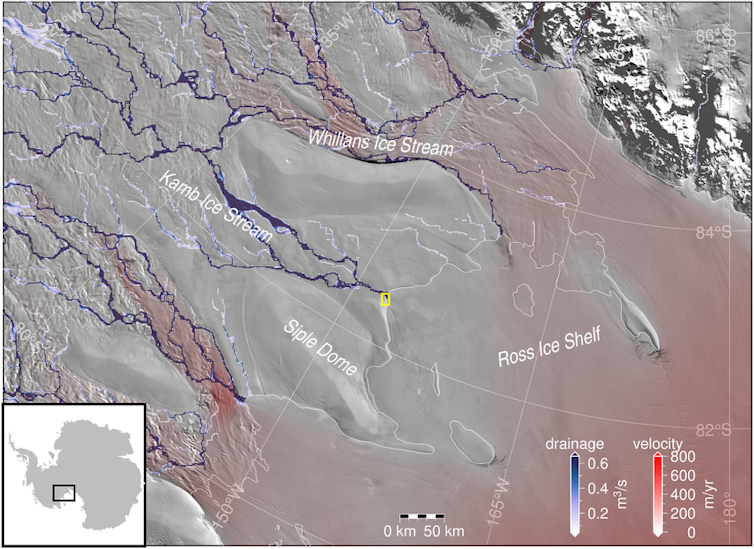

Scientists have considered two possible explanations for this past ice sheet retreat and advance. The first is related to Earth’s crust below the ice sheet.

As an ice sheet shrinks, the change in ice mass causes the Earth’s crust to slowly uplift in response. At the same time, and counterintuitively, the sea level drops near the ice because of a weakening of the gravitational attraction between the ice sheet and the ocean water.

As the ice sheet thinned and retreated since the last ice age, crustal uplift and the fall in sea level in the region may have re-grounded floating ice, causing ice sheet advance.

AGU, CC BY-SA

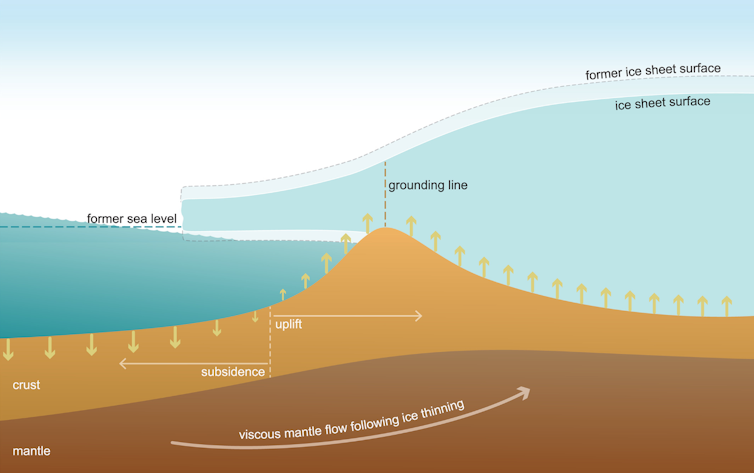

The other hypothesis is that the ice sheet behaviour may be due to changes in the ocean. When the surface of the ocean freezes, forming sea ice, it expels salt into the water layers below. This cold briny water is heavier and mixes deep into the ocean, including under the Ross Ice Shelf. This blocks warm ocean currents from melting the ice.

AGU, CC BY-SA

Seafloor sediments and ice cores tell us that this deep mixing was weaker in the past when the ice sheet was retreating. This means that warm ocean currents may have flowed underneath the ice shelf and melted the ice. Mixing increased when the ice sheet was advancing.

We test these two ideas with computer model simulations of ice sheet flow and Earth’s crustal and sea surface responses to changes in the ice sheet with varying ocean temperature.

Because the rate of crustal uplift depends on the viscosity (stickiness) of the underlying mantle, we ran simulations within ranges estimated for West Antarctica. A stickier mantle means slower crustal uplift as the ice sheet thins.

The simulations that best matched geological records had a stickier mantle and a warmer ocean as the ice sheet retreated. In these simulations, the ice sheet retreats more quickly as the ocean warms.

When the ocean cools, the simulated ice sheet readvances to its present-day position. This means that changes in ocean temperature best explain the past ice sheet behaviour, but the rate of crustal uplift also affects how sensitive the ice sheet is to the ocean.

Veronika Meduna, CC BY-SA

What this means for climate policy today

Much attention has been paid to recent studies that show glacial melting may be irreversible in some parts of West Antarctica, such as the Amundsen Sea embayment.

In the context of such studies, policy debates hinge on whether we should focus on adapting to rising seas rather than cutting greenhouse gas emissions. If the ice sheet is already melting, are we too late for mitigation?

Our study suggests it is premature to give up on mitigation.

Global climate models run under high-emissions scenarios show less sea ice formation and deep ocean mixing. This could lead to the same cold-to-warm ocean switch that caused extensive ice sheet retreat thousands of years ago.

For West Antarctica’s Siple Coast, it is better if we prevent this ocean warming from occurring in the first place, which is still possible if we choose a low-emissions future.

Science

NASA's Voyager 1 resumes sending engineering updates to Earth – Phys.org

For the first time since November, NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft is returning usable data about the health and status of its onboard engineering systems. The next step is to enable the spacecraft to begin returning science data again. The probe and its twin, Voyager 2, are the only spacecraft to ever fly in interstellar space (the space between stars).

Voyager 1 stopped sending readable science and engineering data back to Earth on Nov. 14, 2023, even though mission controllers could tell the spacecraft was still receiving their commands and otherwise operating normally. In March, the Voyager engineering team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California confirmed that the issue was tied to one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers, called the flight data subsystem (FDS). The FDS is responsible for packaging the science and engineering data before it’s sent to Earth.

The team discovered that a single chip responsible for storing a portion of the FDS memory—including some of the FDS computer’s software code—isn’t working. The loss of that code rendered the science and engineering data unusable. Unable to repair the chip, the team decided to place the affected code elsewhere in the FDS memory. But no single location is large enough to hold the section of code in its entirety.

So they devised a plan to divide affected the code into sections and store those sections in different places in the FDS. To make this plan work, they also needed to adjust those code sections to ensure, for example, that they all still function as a whole. Any references to the location of that code in other parts of the FDS memory needed to be updated as well.

The team started by singling out the code responsible for packaging the spacecraft’s engineering data. They sent it to its new location in the FDS memory on April 18. A radio signal takes about 22.5 hours to reach Voyager 1, which is over 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from Earth, and another 22.5 hours for a signal to come back to Earth. When the mission flight team heard back from the spacecraft on April 20, they saw that the modification had worked: For the first time in five months, they have been able to check the health and status of the spacecraft.

During the coming weeks, the team will relocate and adjust the other affected portions of the FDS software. These include the portions that will start returning science data.

Voyager 2 continues to operate normally. Launched over 46 years ago, the twin Voyager spacecraft are the longest-running and most distant spacecraft in history. Before the start of their interstellar exploration, both probes flew by Saturn and Jupiter, and Voyager 2 flew by Uranus and Neptune.

Provided by

NASA

Citation:

NASA’s Voyager 1 resumes sending engineering updates to Earth (2024, April 22)

retrieved 22 April 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-04-nasa-voyager-resumes-earth.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

-

Business18 hours ago

Honda to build electric vehicles and battery plant in Ontario, sources say – Global News

-

Science19 hours ago

Science19 hours agoWill We Know if TRAPPIST-1e has Life? – Universe Today

-

Investment22 hours ago

Down 80%, Is Carnival Stock a Once-in-a-Generation Investment Opportunity?

-

Health18 hours ago

Health18 hours agoSimcoe-Muskoka health unit urges residents to get immunized

-

Health15 hours ago

Health15 hours agoSee how chicken farmers are trying to stop the spread of bird flu – Fox 46 Charlotte

-

Investment17 hours ago

Investment17 hours agoOwn a cottage or investment property? Here's how to navigate the new capital gains tax changes – The Globe and Mail

-

News23 hours ago

Honda expected to announce multi-billion dollar deal to assemble EVs in Ontario

-

Science24 hours ago

Science24 hours agoWatch The World’s First Flying Canoe Take Off