Art

New Blanton Museum of Art Exhibition Showcases the Talents of Artist Terry Allen – The Alcalde

Terry Allen’s creative process is a mystery—even to him. In fact, he never knows where inspiration will take him. Though he creates works in many disciplines, Allen first became well-known as one of the greatest narrative songwriters in country music, beginning with the cult outlaw 1975 concept album Juarez. Though he’s still writing and releasing complex country albums—the most recent being 2020’s Just Like Moby Dick—Allen’s work as a visual artist at least equals that of his storied musical career.

But the former Guggenheim Fellow and multiple NEA grant awardee with pieces in collections across the world, including at the Museum of Modern Art and the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, creates art without much consideration for its resulting media. He doesn’t find inspiration and think to himself, that’s a song, or, that’s definitely just a painting. Hell, sometimes it’s both. Such is the case in many of his pieces in MemWars, an art exhibition that opened at the Blanton Museum of Art on Dec. 18, that deals with, as Allen puts it, “that battlefield of memory, I suppose.”

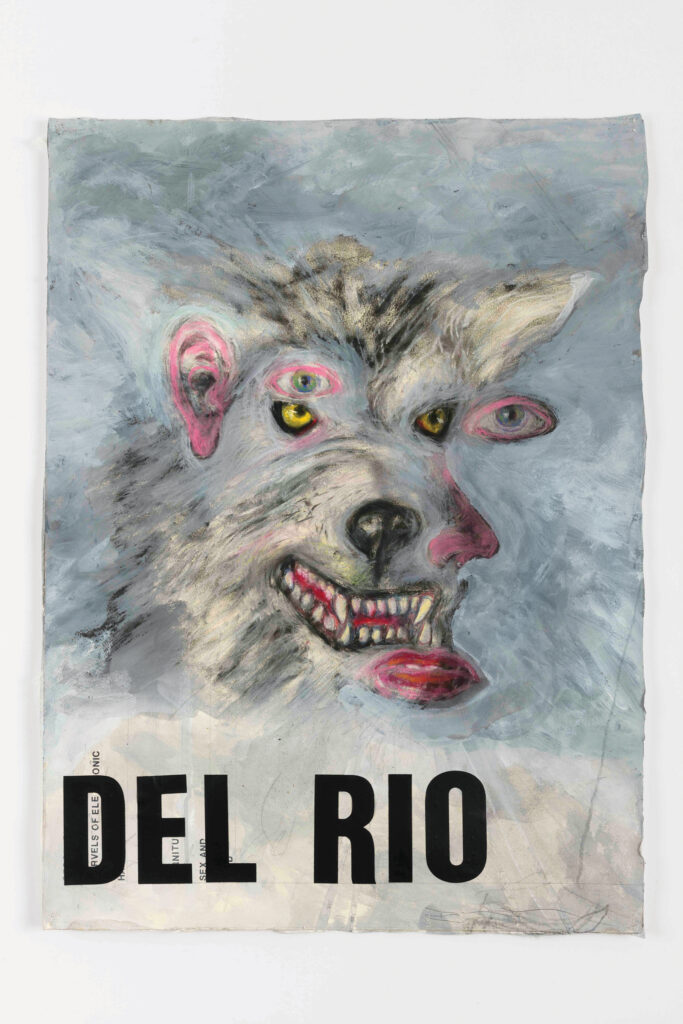

“Wolfman of del Rio (MemWars),” for instance, a mixed media on paper piece created between 2018-19, shares a title with the fourth track on Allen’s 1979 double album Lubbock (On Everything). In the painting, images of a man and a wolf merge, just as the past does with the present, and, above all, Allen’s musical life becomes indistinguishable from his visual art. Essentially, that’s how he creates.

“They’ve always been one thing to me. Playing music or making visual pieces—whatever your sense of curiosity or wherever that takes you, I’m game for it,” Allen says. “That thing of trying to categorize things … I’m really not interested in that.”

“Wolfman” joins approximately 21 other drawings, “hung densely,” per Allen’s request of Blanton Deputy Director of Curatorial Affairs Carter E. Foster, on one side of a long, black curtain in the Contemporary Gallery upstairs at the museum. Opposite that is a multi-screen video installation, with Allen on one side and his wife, artist and writer Jo Harvey Allen, on the other. They alternate telling stories about possible origins of songs, after which both faces disappear and Allen appears on a third screen, performing with his back to the audience as he and his piano roar down a long, flat highway for over an hour. The video is not necessarily connected to the other visual pieces, according to Allen, but similar themes arise when the exhibition is considered holistically.

“It’s always a mystery where a song comes from, even at the most obvious, it’s still a mystery that it becomes a song to me,” Allen says. “That piece kind of deals with that idea.”

Allen met Foster through a mutual friend, museum director Kippy Stroud, who ran a residency each year in Maine for artists, writers, and curators. About 10 years ago, both were in Maine, and Foster saw Allen’s artwork at a residency presentation. Foster says it “seemed crazy not to” put on a contemporary art show for Terry Allen at the Blanton when another colleague suggested it. Before then, though, in 2015, Stroud died suddenly during one of the residencies. In acknowledgement of Stroud bringing Allen and Foster together, MemWars includes a piece called “Song For Kippy.”

“She had an everlasting influence on everyone she came into contact with, and I’m not sure if she even really knew it, the impact that she had on people,” Allen says. “But then that to me was a real anchor in this show.”

Much of the exhibition touches on people like Stroud, whose experiences have made deep impressions on Allen. One piece is about his cousin’s failed attempt at a second act as a professional archer following a dishonorable discharge during his fourth tour of Vietnam. “The war basically killed him, but it took about 40 years to do it,” Allen says.

Another, “Roadrunner,” is about a high school friend who was killed during the early days of Vietnam. A champion high school track and field athlete, he had roadrunners tattooed on his calves, and when he died in battle, he was identified by those markings. Astute Allen listeners might recognize the name from “Blue Asian Reds (for Roadrunner),” a 1979 song written from the perspective of his friend’s grieving girlfriend.

“He was the first person that made the war real to me,” Allen says. “I was at art school in California and got a call that he had been blown up in Vietnam. And it was just inconceivable to me to this human that I knew and was a friend of mine was there. There’s some pieces in the show that address that.”

Allen says that though these pieces deal with the battlefield of his memory—and often real war settings—his work is not born out of some cathartic triumph over emotion.

“It’s pretty cold-blooded when you make something,” he says. “You just make this thing and then you stand back and maybe try to come to terms with it and figure out what it is. But it’s really about the thing. It’s not about you; it’s about what you make.”

MemWars runs until July 10, 2022, at the Blanton Museum of Art.

CREDITS: © Terry Allen, Courtesy of L.A . Louver, Venice, CA

Art

Art and Ephemera Once Owned by Pioneering Artist Mary Beth Edelson Discarded on the Street in SoHo – artnet News

This afternoon in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, people walking along Mercer Street were surprised to find a trove of materials that once belonged to the late feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson, all free for the taking.

Outside of Edelson’s old studio at 110 Mercer Street, drawings, prints, and cut-out figures were sitting in cardboard boxes alongside posters from her exhibitions, monographs, and other ephemera. One box included cards that the artist’s children had given her for birthdays and mother’s days. Passersby competed with trash collectors who were loading the items into bags and throwing them into a U-Haul.

“It’s her last show,” joked her son, Nick Edelson, who had arranged for the junk guys to come and pick up what was on the street. He has been living in her former studio since the artist died in 2021 at the age of 88.

Naturally, neighbors speculated that he was clearing out his mother’s belongings in order to sell her old loft. “As you can see, we’re just clearing the basement” is all he would say.

Photo by Annie Armstrong.

Some in the crowd criticized the disposal of the material. Alessandra Pohlmann, an artist who works next door at the Judd Foundation, pulled out a drawing from the scraps that she plans to frame. “It’s deeply disrespectful,” she said. “This should not be happening.” A colleague from the foundation who was rifling through a nearby pile said, “We have to save them. If I had more space, I’d take more.”

Edelson’s estate, which is controlled by her son and represented by New York’s David Lewis Gallery, holds a significant portion of her artwork. “I’m shocked and surprised by the sudden discovery,” Lewis said over the phone. “The gallery has, of course, taken great care to preserve and champion Mary Beth’s legacy for nearly a decade now. We immediately sent a team up there to try to locate the work, but it was gone.”

Sources close to the family said that other artwork remains in storage. Museums such as the Guggenheim, Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney currently hold her work in their private collections. New York University’s Fales Library has her papers.

Edelson rose to prominence in the 1970s as one of the early voices in the feminist art movement. She is most known for her collaged works, which reimagine famed tableaux to narrate women’s history. For instance, her piece Some Living American Women Artists (1972) appropriates Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1494–98) to include the faces of Faith Ringgold, Agnes Martin, Yoko Ono, and Alice Neel, and others as the apostles; Georgia O’Keeffe’s face covers that of Jesus.

A lucky passerby collecting a couple of figurative cut-outs by Mary Beth Edelson. Photo by Annie Armstrong.

In all, it took about 45 minutes for the pioneering artist’s material to be removed by the trash collectors and those lucky enough to hear about what was happening.

Dealer Jordan Barse, who runs Theta Gallery, biked by and took a poster from Edelson’s 1977 show at A.I.R. gallery, “Memorials to the 9,000,000 Women Burned as Witches in the Christian Era.” Artist Keely Angel picked up handwritten notes, and said, “They smell like mouse poop. I’m glad someone got these before they did,” gesturing to the men pushing papers into trash bags.

A neighbor told one person who picked up some cut-out pieces, “Those could be worth a fortune. Don’t put it on eBay! Look into her work, and you’ll be into it.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Art

Biggest Indigenous art collection – CTV News Barrie

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Biggest Indigenous art collection CTV News Barrie

Source link

Art

Why Are Art Resale Prices Plummeting? – artnet News

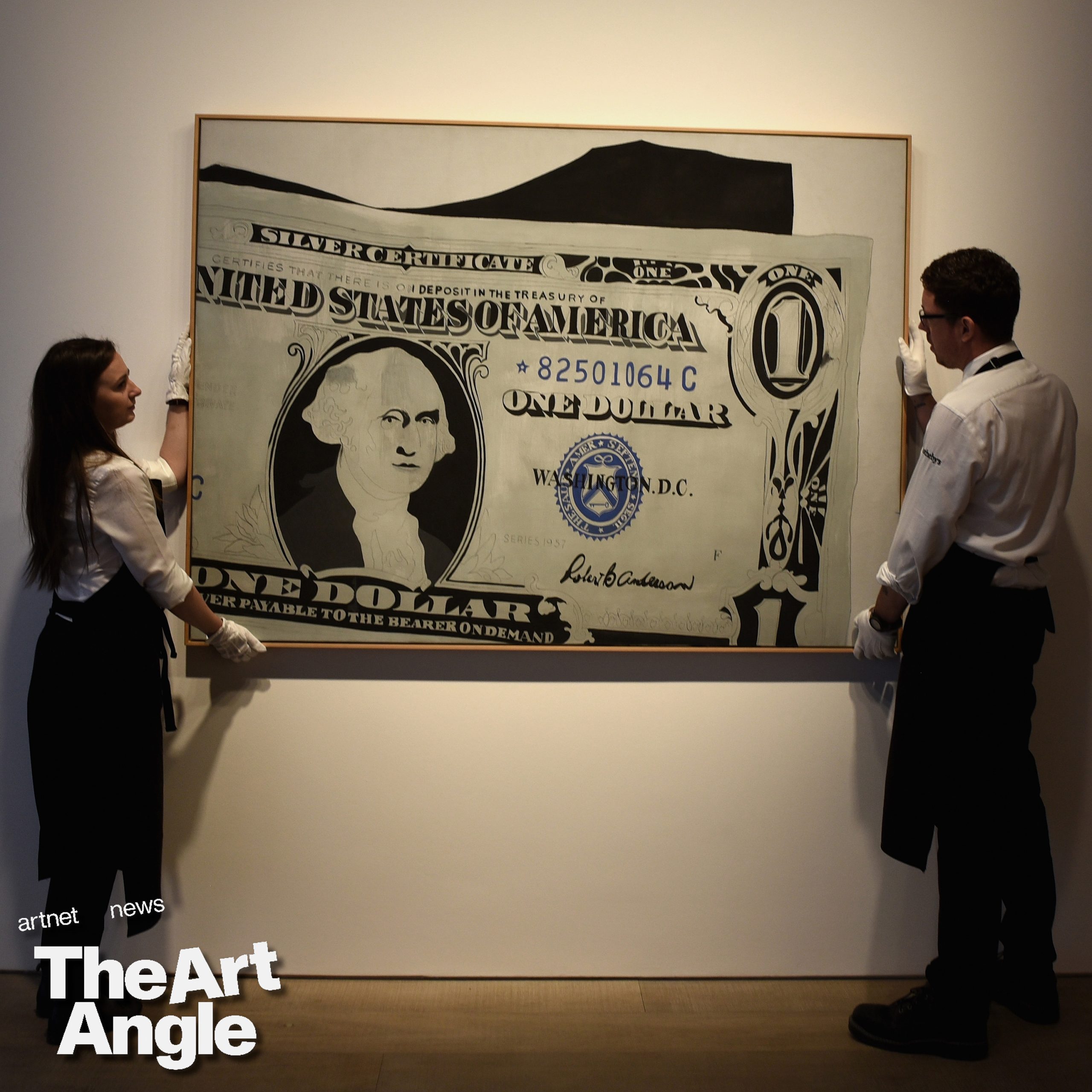

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

-

Media15 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Media17 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Investment16 hours ago

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

-

Sports20 hours ago

Sports20 hours ago2024 Stanley Cup Playoffs 1st-round schedule – NHL.com

-

Real eState8 hours ago

Botched home sale costs Winnipeg man his right to sell real estate in Manitoba – CBC.ca

-

News14 hours ago

Canada Child Benefit payment on Friday | CTV News – CTV News Toronto

-

Business16 hours ago

Gas prices see 'largest single-day jump since early 2022': En-Pro International – Yahoo Canada Finance

-

Art19 hours ago

Enter the uncanny valley: New exhibition mixes AI and art photography – Euronews