Art

Opinion: Art as an investment hedge is returning amid inflation and a choppy market

|

|

:format(jpeg)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/DQ5KUP2CLRPCPH5D66JOKH3URY.jpg)

Pablo Picasso’s ‘Guitare sur une table’ from 1919 appeared on the market for the first time in 75 years.Michael Bowles/Getty Images

Gus Carlson is a New York-based columnist for The Globe and Mail

The numbers were eye-popping even for the movers and shakers in the rarefied air of the world’s fine-art markets.

The Christie’s New York fall auction of Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen’s collection last week cleared US$1.5-billion, including five works that sold for more than US$100-million apiece. A Sotheby’s New York auction of the collection of CBS founder William Paley took in almost US$50-million this week, including US$37.5-million for Pablo Picasso’s Guitar on a Table, purchased by the media tycoon in 1946.

Beyond the wow power of the big names and the big price tags, the sales shone a bright light on an increasingly popular investment strategy, even for people who don’t know their Klimt from their Klee: art as a hedge in an inflationary time, when financial markets are choppy and recession looms.

“Art is so stable because its value is not tied to the economy or how it performs,” said Emily Greenspan, the founder of TAG ARTS, a Los Angeles art consultancy, who has seen an uptick in interest from clients looking to diversify their portfolios with something other than the usual stocks and bonds. “It really is a safe, solid place to put your money – safer than the stock market or real estate.”

Art experts say there have been only two meaningful downward blips in the market over the past two decades: the financial crisis of 2007-08 and the pandemic.

To be sure, while art has real appeal as a tangible asset, caveat emptor. The market is not regulated, so if a collector buys a work that does not increase in value, no one will make them whole. As well, the art market’s 2022 price spike is daunting to new investors.

And then of course there’s the risk of buying a fake. Even respected galleries have been burned by greedy fraudsters and highly skilled counterfeiters. In the US$80-million case involving New York’s Knoedler & Company, painter Pei-Shen Qian was able to fool countless collectors and dealers with works claimed to be those of artists such as Mark Rothko and Jackson Pollock.

Another issue is that just because an investor has money doesn’t mean they can walk into a gallery and buy what they like. There is a credential-building process because there are often waiting lists for popular artists, and novice collectors must get in line behind museums and recognized collectors.

Can wine, art, and other collectibles work as hedges against inflation?

“Galleries want to see the value of the art and the artists protected over the long term,” Ms. Greenspan said. “They want to know if you’re for real and what you plan to do with the work over time.”

And unlike real estate, flipping is considered taboo in the art world. Flippers risk being blackballed by galleries and will have to fight it out at auction.

But there is no question that art as an investment is becoming more popular. Investors themselves are a more diverse group these days – from young tech entrepreneurs to foreign investors to young families looking to diversify their holdings and get personal enjoyment from the art as well.

That is because there are many ways to get in, even for those who have no interest or experience in collecting – or the money to buy expensive pieces at auction.

Art funds are becoming more popular as ways for average investors to diversify without having to learn anything about art. Investors bank on the market expertise of the fund managers, who buy and sell art, to increase the value of the portfolio and deliver returns.

For investors who are also wannabe collectors, Ms. Greenspan advises to wait for off-peak auctions and sales, where there is a good chance to find works by up-and-comers and unheralded works by famous artists. As she says, even a lesser-known Picasso will always be a Picasso.

“Watch the trends like you would in any investment market,” she said. Still, “it is a crapshoot as to who will be the next hot commodity.”

As for what’s hot now, the Black Lives Matter movement generated a boom for African-American artists such as Derek Fordjour, Charles Gaines, Mark Bradford and Kehinde Wiley. Black women artists are in especially high demand, among them: Mickalene Thomas, Amy Sherald and Njideka Akunyili Crosby.

“Art is a cultural touchstone,” Ms. Greenspan said, “and museums try to reflect that in their collections.”

Art

Art and Ephemera Once Owned by Pioneering Artist Mary Beth Edelson Discarded on the Street in SoHo – artnet News

This afternoon in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, people walking along Mercer Street were surprised to find a trove of materials that once belonged to the late feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson, all free for the taking.

Outside of Edelson’s old studio at 110 Mercer Street, drawings, prints, and cut-out figures were sitting in cardboard boxes alongside posters from her exhibitions, monographs, and other ephemera. One box included cards that the artist’s children had given her for birthdays and mother’s days. Passersby competed with trash collectors who were loading the items into bags and throwing them into a U-Haul.

“It’s her last show,” joked her son, Nick Edelson, who had arranged for the junk guys to come and pick up what was on the street. He has been living in her former studio since the artist died in 2021 at the age of 88.

Naturally, neighbors speculated that he was clearing out his mother’s belongings in order to sell her old loft. “As you can see, we’re just clearing the basement” is all he would say.

Photo by Annie Armstrong.

Some in the crowd criticized the disposal of the material. Alessandra Pohlmann, an artist who works next door at the Judd Foundation, pulled out a drawing from the scraps that she plans to frame. “It’s deeply disrespectful,” she said. “This should not be happening.” A colleague from the foundation who was rifling through a nearby pile said, “We have to save them. If I had more space, I’d take more.”

Edelson’s estate, which is controlled by her son and represented by New York’s David Lewis Gallery, holds a significant portion of her artwork. “I’m shocked and surprised by the sudden discovery,” Lewis said over the phone. “The gallery has, of course, taken great care to preserve and champion Mary Beth’s legacy for nearly a decade now. We immediately sent a team up there to try to locate the work, but it was gone.”

Sources close to the family said that other artwork remains in storage. Museums such as the Guggenheim, Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney currently hold her work in their private collections. New York University’s Fales Library has her papers.

Edelson rose to prominence in the 1970s as one of the early voices in the feminist art movement. She is most known for her collaged works, which reimagine famed tableaux to narrate women’s history. For instance, her piece Some Living American Women Artists (1972) appropriates Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1494–98) to include the faces of Faith Ringgold, Agnes Martin, Yoko Ono, and Alice Neel, and others as the apostles; Georgia O’Keeffe’s face covers that of Jesus.

A lucky passerby collecting a couple of figurative cut-outs by Mary Beth Edelson. Photo by Annie Armstrong.

In all, it took about 45 minutes for the pioneering artist’s material to be removed by the trash collectors and those lucky enough to hear about what was happening.

Dealer Jordan Barse, who runs Theta Gallery, biked by and took a poster from Edelson’s 1977 show at A.I.R. gallery, “Memorials to the 9,000,000 Women Burned as Witches in the Christian Era.” Artist Keely Angel picked up handwritten notes, and said, “They smell like mouse poop. I’m glad someone got these before they did,” gesturing to the men pushing papers into trash bags.

A neighbor told one person who picked up some cut-out pieces, “Those could be worth a fortune. Don’t put it on eBay! Look into her work, and you’ll be into it.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Art

Biggest Indigenous art collection – CTV News Barrie

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Biggest Indigenous art collection CTV News Barrie

Source link

Art

Why Are Art Resale Prices Plummeting? – artnet News

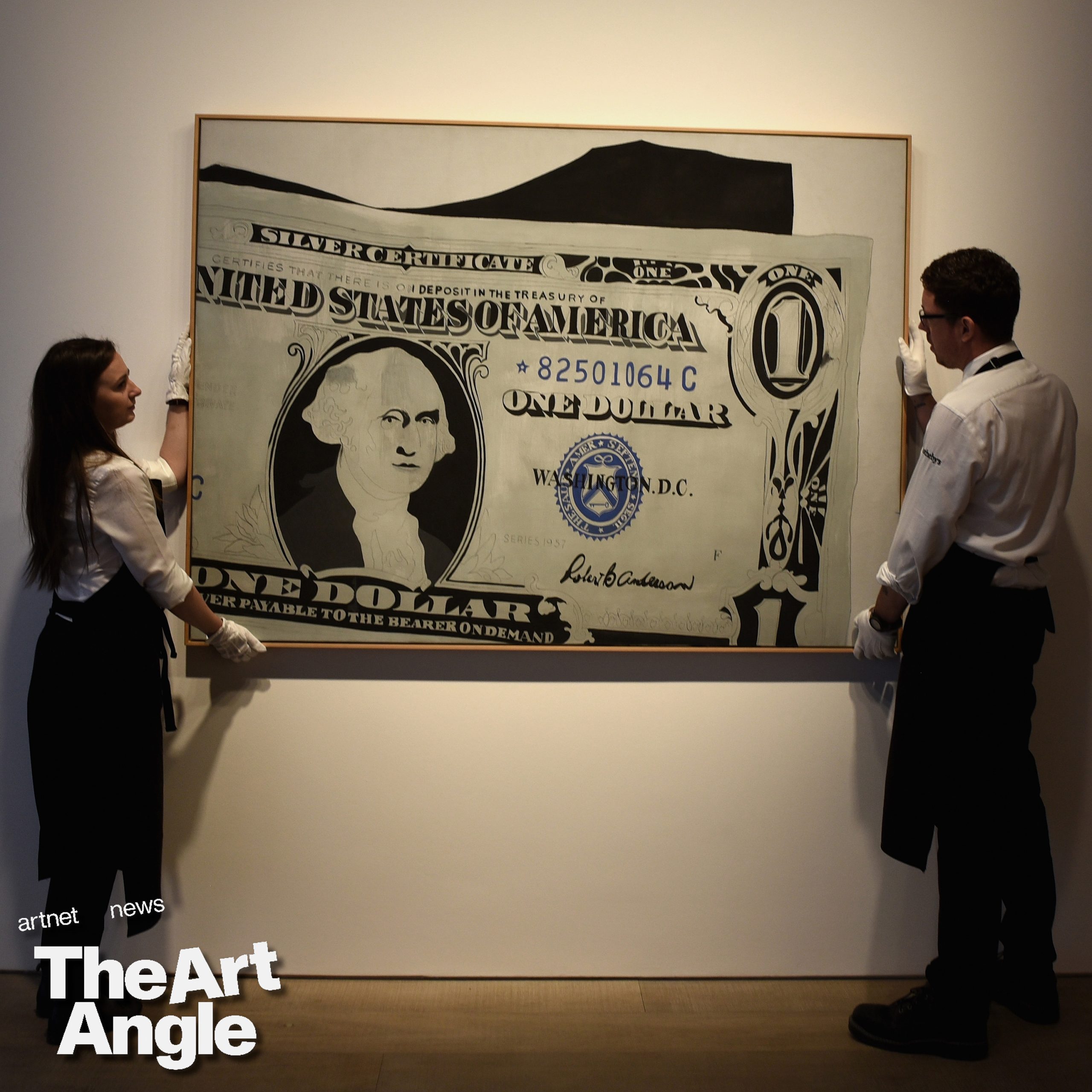

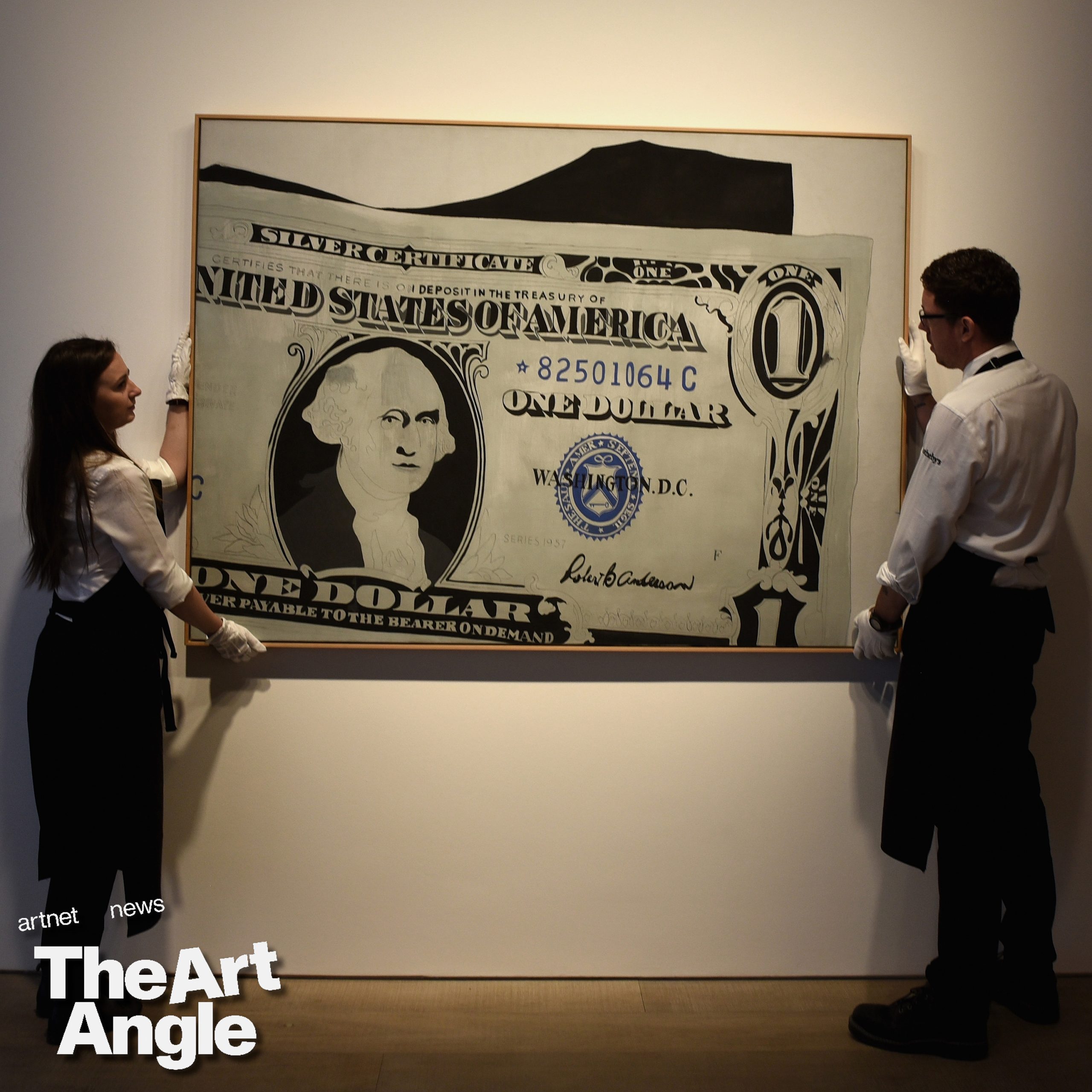

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

-

Media13 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Media16 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Investment14 hours ago

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

-

Sports19 hours ago

Sports19 hours ago2024 Stanley Cup Playoffs 1st-round schedule – NHL.com

-

Investment23 hours ago

Investment23 hours agoWant to Outperform 88% of Professional Fund Managers? Buy This 1 Investment and Hold It Forever. – The Motley Fool

-

Business14 hours ago

Gas prices see 'largest single-day jump since early 2022': En-Pro International – Yahoo Canada Finance

-

Real eState6 hours ago

Botched home sale costs Winnipeg man his right to sell real estate in Manitoba – CBC.ca

-

Health23 hours ago

Health23 hours agoToronto reports 2 more measles cases. Use our tool to check the spread in Canada – Toronto Star