Talk to almost anyone today about social media, and you’ll hear that it’s toxic. One might diagnose it with having an excess of outrage, another too little free speech. Some bemoan the invasion of privacy, the scourge of lies and hate, the capricious rule of technology titans, the trashing of attention spans. And some feel that no matter how delicious any morsel it offers, the indulgence leaves a bad aftertaste.

Media

Opinion | How to make social media better – The Washington Post

The pendulum has fully swung from early Pollyanna predictions that social media would unite families and topple repressive regimes to today’s declarations that it is depressing teenagers and destroying democracy. Frustration is widespread; calls for change cross the political aisle. Pioneers have decamped from Twitter and Facebook to join experimental platforms such as Mastodon and Post, despite clunky features and the sacrifice of caches of followers and friends.

But for many of us, the dream of digital town squares where we openly discuss important matters has lost its luster. Messaging apps such as WhatsApp and Facebook Messenger, where chats take place in private groups, have for years been more popular than broadcasting thoughts to a public feed. And who can blame teenagers for preferring TikTok? Even on a good day, a whimsical video has more appeal than a heated exchange with a vitriolic stranger.

Meanwhile, the technologies and the talent pool to create new kinds of online communities are expanding. Thousands of workers have left Big Tech companies in recent months, some of whom itch to do something civic-minded. While building social networks once took a great deal of money and technical expertise, today’s wannabe hosts can use open-source protocols and their own servers to build micro-communities that offer users more control over content, privacy and the rules of the road.

Even in Washington, the political will to change the status quo is growing. Last year, bipartisan bills targeting the downsides of digital platforms emerged in both chambers of Congress. Though there’s still no consensus about what to do, there’s an emerging consensus that something must be done about social media.

Where all this momentum leads is anyone’s guess. But there’s no going back to a world before Facebook, however pretty it might look in the foggy rearview mirror. What we should hope for instead is a new era of social media — one that serves the best interests of society instead of exploiting its worst impulses. To get there will require new business models and funding sources — and probably some smart and not heavy-handed legislation. It also will require something sorely lacking from most social media conversations today: imagination.

How do we want to gather online in the future? What would lively, inviting, edifying social media communities give us, and how would they look and feel? Whom do we want to connect with, and on what terms? What kinds of conversations and content do we want to see and share? And most important, whom do we want to make choices about something that has become essential to the way we interact with one another, the way we learn about the world, and the way we impart what we know?

Most of us haven’t asked ourselves these questions. We accept the social media we have, perhaps out of convenience or because it’s all we know.

“We basically have two problems in digital governance: one, not knowing what we want; and two, not trusting people to give it to us,” said Jonathan Zittrain, faculty director of Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. “When we imagine a solution, we still think about Facebook and Twitter, single communities of millions or billions of people where one statement might get exposed to 10 million or 100 million people in the span of 24 hours.”

It’s little wonder that the prevailing platforms have become so noxious. The for-profit companies such as Meta and Twitter that host them rely on advertising for revenue; the more engaged we are by what we see, the more ad dollars they earn. Polarizing content creates stronger reactions and therefore more sharing and commenting, so social media companies’ algorithms amplify it. The profit scheme favors conflict.

Swashbuckling entrepreneurs now decide whether a post should be taken down — whether it’s merely an unpopular viewpoint or an outright lie, whether it’s mild nudity or a neo-Nazi slur. These men are not sufficiently motivated by the marketplace or their consciences to cultivate communities that inform the masses with the truth, to surface nuance on public matters, or to protect our privacy from companies that seek to sell us their wares.

We stay because we still get something from social media. Facebook, Instagram and Twitter can feel like thriving cities where we already know a lot of people and our way around. This makes it hard to leave — despite discontent with our interactions or with how Mark Zuckerberg and Elon Musk police our posts, or welcome trolls to the party.

Mercifully, the possibility for a different kind of social media — where we could get more of what we like and less of what we don’t — is opening up.

Divya Siddarth, co-founder of a new effort to create more community control of emerging technologies called the Collective Intelligence Project, said it’s becoming easier to choose what kinds of online communities we want. Technology models such as federated networks, which underlie Mastodon, the ascendant Twitter refuge, allow people to choose from a range of options for privacy, transparency of identity and social norms in smaller communities linked to a common hub.

Innovators are creating ranking systems that would enable people to vote on a community’s content-moderation algorithm based on what it amplifies and suppresses, rather than accept a single company’s default strategy. Researchers are working on algorithms that would “bridge” divides, amplifying not what’s causing strong reactions but what people of various persuasions, whether political affiliations or musical tastes, agree on. In the future, people might be able to choose algorithms or entire networks that expose them to ideas from diverse sources and surface consensus views, and that also might better prevent harassment and hate speech.

Progress in artificial intelligence, including large language models such as ChatGPT — although it poses risks such as spreading more misinformation — could also help, Siddarth said, by summarizing convergence areas on hot topics or translating across languages to bring more people around the globe into online conversations.

“We have this core desire for community, and people are creative about using the internet in ways that go around the existing incentive structures,” she said. “A lot of people are experimenting and bootstrapping in this space.”

That experimentation has yet to yield vibrant and enticing alternatives to the cities we inhabit on the big social media sites. But with the right kind of thinking, investment and policy, it could.

Eli Pariser, author of “The Filter Bubble” and co-director of New_Public, believes next-generation digital platforms should be public spaces, such as the parks, libraries and trails where we go in the real world to have fun, exercise, learn, meet new friends or connect with old ones, check out public art, and sometimes organize charity drives or have political conversations. In the future social media landscape, Pariser said, people might go to a certain online network to connect with people at their school, a different one to connect with neighbors, and yet another to connect with people in their cities or more globally. New_Public calls itself a community and studio aimed at building such online spaces.

If the idea of encountering more digital spaces sounds overwhelming today, that’s because we don’t yet have seamless ways to move among networks. Each one has its own app, profile, data and connections. But it’s possible to create an open, shared protocol for social media that would enable us to use one or two apps to move among various networks — the way we now send one another email even if our correspondence relies on distinct servers and design interfaces (Gmail, Yahoo Mail and so on). For this to happen, companies will have to be compelled by their customers or the law to make their networks open and interoperable, allowing us to leave without losing our data and to move our profiles and connections around. This would make it easier to spend more time in communities that are better for us.

You might wonder, as I have, whether the social media we have today is the social media we deserve — if human nature is the true driver of all the outrage. But consider that the entire internet is not a cesspool of terrorists and conspiracy theorists. The environments that people inhabit, and their design, matter. Wikipedia, although it is an online encyclopedia and not a social media network, shows what can happen when people are invited to tend their own digital community gardens. Notably, as a nonprofit, this platform was designed not to keep its users addicted, but to share credible information with the public.

Wikipedia has motivated people to build and maintain its compendium of knowledge for free — with a collaborative spirit and remarkable accuracy. A cadre of volunteer editors sets the standards for how entries are added and updated. Conflict, lies, bias and bad faith are not rewarded; editors get demoted or promoted by the community based on their behavior, and their track records are made public.

Former Wikimedia chief executive Katherine Maher believes the next era of social media could similarly let communities govern themselves. “You can get platforms where users have responsibility for content moderation — friendly spaces, safe spaces with robust and meaningful discussion,” she said. Maher suggests that existing media companies hire facilitators charged with listening to their communities and setting the boundaries for what gets amplified and what gets taken down instead of relying on a central authority that farms the job out to people charged with following its rules.

Wikipedia is instructive, too, in that its operation relies on donations. It will probably take public or philanthropic investment — and sustained financial support over time from the government or directly from us via subscription fees — to support the next generation of social media technologies and platforms. The current offerings might seem free, but they come at the cost of our individual and collective well-being. Social media could be freed from its flawed business model if we thought of it as a public good worthy of public investment, similar to roadways, K-12 schools and the military.

That’s not to say that commercial platforms can be expected to disappear. But with more competition and greater capacity for users to leave them, ad-driven companies might be motivated to temper their preference for polarization over community-building. Already, several social media companies are struggling to grow their subscriber numbers.

For all its ills, social media still serves some good in our lives and in our society, and it can one day serve far more. Family and friends still share their milestones. People with rare diseases find solidarity and solace and advocate for cures together. It’s on social media that Iranian women brought worldwide attention to their protests over wearing the hijab and that pro-democracy activists organized in Hong Kong. And it’s still a place to witness awe-inspiring dance routines, optical illusions and, yes, cat antics.

Breaking the stranglehold that existing platforms have on users is not going to be easy. Technology companies will have to play by new rules, and civic leaders must decide to collectively invest in innovation. Just as critical, however, is that we begin to envision alternatives to our current malaise. Capital, political will and people follow good ideas. Without ideas, we may squander the chance to channel discontent into progress.

The first era of social media was designed for us by clever young men with technical expertise and vague notions of connecting people to one another — but not much foresight about how it would change the world. And politicians in their thrall have let them run amok.

Better online communities won’t grow from the same kinds of ideas, companies and thinkers who got us here. The next era should be shaped by the wide public it will serve. The new communities should be designed and shepherded by all of us: artists, teachers, entrepreneurs, policy wonks, nurses, architects, moms, mechanics, community organizers, musicians, writers. It’s our turn to choose the technological future we want.

Can you imagine a different, better kind of social media in the future? Share your ideas here.

Media

Psychology group says infinite scrolling and other social media features are ‘particularly risky’ to youth mental health – NBC News

A top psychology group is urging technology companies and legislators to take greater steps to protect adolescents’ mental health, arguing that social media platforms are built for adults and are “not inherently suitable for youth.”

Social media features such as endless scrolling and push notifications are “particularly risky” to young people, whose developing brains are less able to disengage from addictive experiences and are more sensitive to distractions, the American Psychological Association wrote in a report released Tuesday.

But age restrictions on social media platforms alone don’t fully address the dangers, especially since many kids easily find workarounds to such limits. Instead, social media companies need to make fundamental design changes, the group said in its report.

“The platforms seem to be designed to keep kids engaged for as long as possible, to keep them on there. And kids are just not able to resist those impulses as effectively as adults,” APA chief science officer Mitch Prinstein said in a phone interview. He added that more than half of teens report at least one symptom of clinical dependency on social media.

“The fact that this is interfering with their in-person interactions, their time when they should be doing schoolwork, and — most importantly — their sleep has really important implications,” Prinstein said.

The report did not offer specific changes that social media companies can implement. Prinstein suggested one option could be to change the default experience of social media accounts for children, with functions such as endless scrolling or alerts shut off.

The report comes nearly a year after the APA issued a landmark health advisory on social media use in adolescence, which acknowledged that social media can be beneficial when it connects young people with peers who experience similar types of adversity offline. The advisory urged social media platforms to minimize adolescents’ online exposure to cyberbullying and cyberhate, among other recommendations.

But technology companies have made “few meaningful changes” since the advisory was released last May, the APA report said, and no federal policies have been adopted.

A spokesperson for Meta, the parent company of Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp, disputed the assertion that there have not been changes instituted on its platforms recently. In the last year, Meta has begun showing teens a notification when they spend 20 minutes on Facebook and has added parental supervision tools that allow parents to schedule breaks from Facebook for their teens, according to a list of Meta resources for parents and teenagers. Meta also began hiding more results in Instagram’s search tool related to suicide, self-harm and eating disorders, and launched nighttime “nudges” that encourage teens to close the app when it’s late.

Prinstein said more is still needed.

“Although some platforms have experimented with modest changes, it is not enough to ensure children are safe,” he said.

TikTok and X, formerly known as Twitter, did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

Tuesday’s report comes amid broader concern over the effects of social media on young people. In March, Florida passed a law prohibiting children younger than 14 from having social media accounts and requiring parental consent for those ages 14 and 15. California lawmakers have introduced a bill to protect minors from social media addiction. Dozens of states have sued Meta for what they say are deceptive features that harm children’s and teens’ mental health.

And last month, a book was published by social psychologist Jonathan Haidt that argues that smartphones and social media have created a “phone-based childhood,” sending adolescents’ rates of anxiety, depression and self-harm skyrocketing.

The book, “The Anxious Generation: How the Great Rewiring of Childhood Is Causing an Epidemic of Mental Illness,” has been hotly debated. While it has its detractors, it instantly became a bestseller.

Prinstein said that it’s up to technology companies to protect their youngest users, but parents can also help. He recommended all devices in a family’s household go on top of the refrigerator at 9 p.m. each night to help kids — and parents — get the amount of sleep they need. He also said there is no harm in limiting or postponing a child’s use of social media.

“We have no data to suggest that kids suffer negative consequences if they delay social media use, or if their parents set it for half an hour a day, or an hour a day,” he said.

“If anything, kids tell us, anecdotally, that they like to be able to blame it on their parents and say, ‘Sorry, my parents won’t let me stay on for more than an hour, so I have to get off,’” he added. “It kind of gives them a relief.”

Media

More than mere media bias: How New York prosecutors see Trump's scheme with the National Enquirer – MSNBC

IE 11 is not supported. For an optimal experience visit our site on another browser.

-

Now Playing

More than mere media bias: How New York prosecutors see Trump’s scheme with the National Enquirer

06:15

-

UP NEXT

The real DOJ corruption scandal at the heart of Trump’s criminal trial in New York

11:59

-

Bank with a checkered past and a deep history with Trump raises red flags

07:23

-

Why Republicans are hiding behind the politics of personality

04:23

-

Media whiffs on the news in Trump’s abortion statement as Dobbs becomes weaponized on global scale

09:17

-

U.S. foes exploit Trump’s divisiveness with fake MAGA accounts; China adopts Russian tactics

10:58

-

Judge has enough of Trump’s attacks on family members; extends gag order on ‘defendant’s vitriol’

04:59

-

Combat training for election workers? Arizona braces for Trump-addled election deniers

07:59

-

Maddow joins colleagues in objecting to McDaniel for legitimizing Trump, attacking democracy

11:59

-

Panicking Trump coming up short for civil fraud penalty; no friends stepping up as deadline nears

07:18

-

Putin flexes expansionist muscles as GOP stalling starves Ukraine of military aid

04:25

-

How pro-Trump election officials could make sure your vote doesn’t count

08:19

-

How Russia duped two Republicans with propaganda laundered through fake news sites

03:54

-

‘Massive national security risk’: Trump financial desperation makes access to U.S. secrets dangerous

04:22

-

‘Everything’s for sale’: Trump’s TikTok flip-flop follows disturbing pattern

11:46

-

Maddow calls out glaring contradiction in Katie Britt’s GOP response

03:13

-

‘Incredibly aggressive’: Biden delivers energized State of the Union

10:39

-

Who is Senator Katie Britt? GOP taps Alabama senator with reproductive rights in spotlight

10:43

-

Maddow: This election is a choice ‘between having a democracy and not’

08:37

-

Democrats see opportunities for Biden to take back North Carolina in 2024

08:26

-

Now Playing

More than mere media bias: How New York prosecutors see Trump’s scheme with the National Enquirer

06:15

-

UP NEXT

The real DOJ corruption scandal at the heart of Trump’s criminal trial in New York

11:59

-

Bank with a checkered past and a deep history with Trump raises red flags

07:23

-

Why Republicans are hiding behind the politics of personality

04:23

-

Media whiffs on the news in Trump’s abortion statement as Dobbs becomes weaponized on global scale

09:17

-

U.S. foes exploit Trump’s divisiveness with fake MAGA accounts; China adopts Russian tactics

10:58

Media

The boomer pause: the sign that shows you should really get off social media – The Guardian

Name: The boomer pause.

Age: A split second.

Appearance: An uncomfortably long break.

Does it refer to an entitled pause between statements to show that you, a boomer, own the room? Not quite: it refers to that awkward moment of silence between hitting “record” and speaking that boomers leave when they film their social media posts.

I’m not sure I understand. It’s like the millennial pause, but longer.

Wait – the millennial pause? A term, coined in 2021, for the telltale split-second pause millennials leave before speaking, because they came of age before TikTok.

And the boomer pause is longer, because boomers are even older? Exactly. Like a long pause before and after speaking.

So it’s a pause indicating age-related technological ineptitude? It’s more than that.

With an added note of self-satisfied indifference about how you come across? That’s part of it, I guess.

And a studied refusal to get to grips with even the most basic and user-friendly editing features? It’s just being a boomer, really.

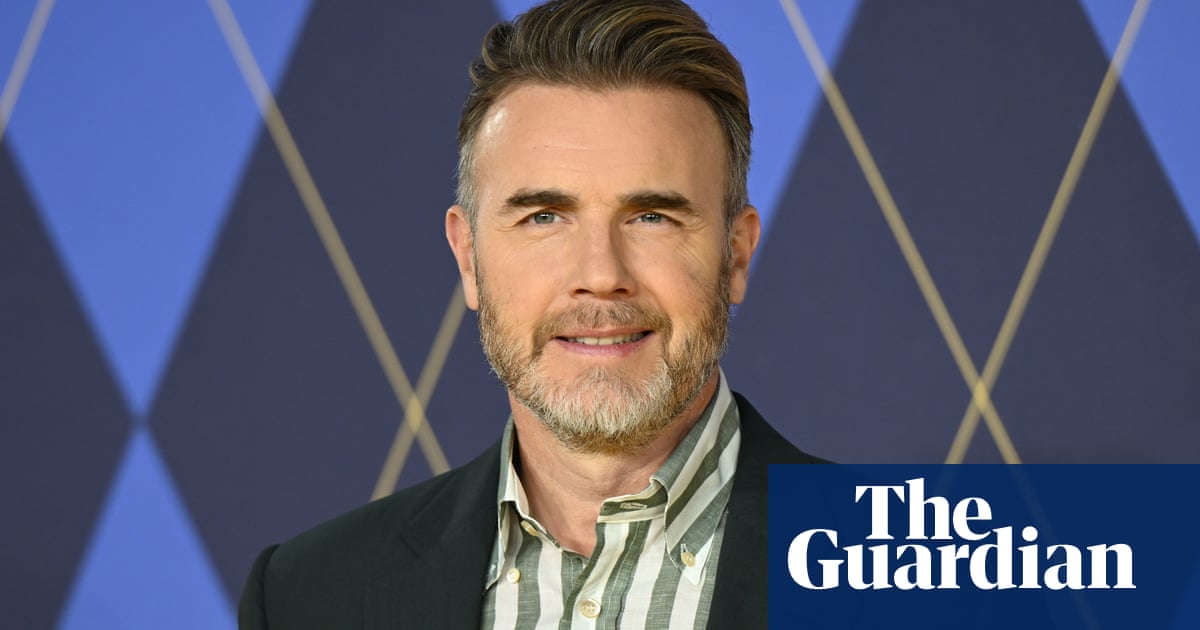

Would you happen to have a popular example of the phenomenon to hand? Yes: Gary Barlow.

From Take That? That’s the one. On the TikTok account of his wine range, Barlow recently filmed himself grinning in front of a vineyard.

Gary Barlow has a wine range? Keep up. The clip, which has since gone viral, may be transcribed thus: (IMMENSE PAUSE). Barlow: “This is my idea of a very nice day out.” (SECOND IMMENSE PAUSE). End of video.

A boomer pause? “I thought my phone had frozen” was one of the many comments below the post.

Maybe he’s inserting a deliberate pause to … To what?

… to capture your attention. TikTok doesn’t work like that, grandad.

Anyway, I hate to break it to you, but Gary Barlow isn’t a boomer. Are you kidding? He has his own wine range, and homes worth millions in London, Oxfordshire and Santa Monica.

Barlow was born in 1971. The generally acknowledged boomer cutoff is 1964. He is technically Gen X. The boomer pause is down to the length of the gap, not the age of the pauser.

So Kylie Jenner could leave a boomer pause? She could, but she wouldn’t.

Do say: (After counting to five slowly in your head) “Hi, everybody!”

Don’t say: “I am pushing the button! It just keeps flashing this … oops, I think we’re on. Hi, everybody!”

-

Media19 hours ago

DJT Stock Plunges After Trump Media Files to Issue Shares

-

Business18 hours ago

FFAW, ASP Pleased With Resumption of Crab Fishery – VOCM

-

Media18 hours ago

Marjorie Taylor Greene won’t say what happened to her Trump Media stock

-

Business19 hours ago

Javier Blas 10 Things Oil Traders Need to Know About Iran's Attack on Israel – OilPrice.com

-

Media17 hours ago

Trump Media stock slides again to bring it nearly 60% below its peak as euphoria fades – National Post

-

Politics19 hours ago

Politics19 hours agoIn cutting out politics, A24 movie 'Civil War' fails viewers – Los Angeles Times

-

Investment20 hours ago

A Once-in-a-Generation Investment Opportunity: 1 Top Artificial Intelligence (AI) Stock to Buy Hand Over Fist in April … – Yahoo Finance

-

Real eState12 hours ago

Real estate mogul concerned how Americans will deal with squatters: ‘Something really bad is going to happen’ – Fox Business