Economy

President Joe Biden’s top economic adviser, Brian Deese leaving White House

|

|

WASHINGTON (AP) — President Joe Biden’s top economic adviser, Brian Deese, is leaving his post.

Biden said Thursday in a statement that Deese would step down as director of the White House National Economic Council. That position had him coordinating policy across the government and negotiating with Congress on coronavirus aid, the budget, infrastructure, the tax code, clean energy incentives, investments in computer chip plants and other measures that the president counts as key victories.

“Brian has a unique ability to translate complex policy challenges into concrete actions that improve the lives of American people,” Biden said. “He has helped steer my economic vision into reality, and managed the transition of our historic economic recovery to steady and stable growth.”

It was the second major departure in recent weeks, as White House Chief of Staff R on Klain is also leaving and being succeeded by Jeff Zients, who previously led the administration’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Deese leaves with the economy having so far avoided a recession that many economists anticipated as the Federal Reserve has lowered inflation by slowing down the economy. Unemployment is at a low 3.5% and semiconductor companies are building new plants, while automakers are shifting toward greater production of electric vehicles.

.

Josh Boak, The Associated Press

Economy

Charting the Global Economy: Fed Delay Recalibrates All Rates – BNN Bloomberg

(Bloomberg) — Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell signaled US central bankers will wait longer to cut borrowing costs following a series of surprisingly high inflation readings, which reduces room for easier policy around the world.

Global finance chiefs convening in Washington for the International Monetary Fund-World Bank spring meetings are sweating the strength of the US economy, as elevated interest rates and a strong dollar force other currencies lower and complicate plans to bring down borrowing costs.

Meanwhile, an escalation of the conflict in the Middle East is raising concerns of a wider regional war that could send oil prices over $100 a barrel.

Here are some of the charts that appeared on Bloomberg this week on the latest developments in the global economy, geopolitics and markets:

World

The high tide for global interest rates has passed, but respite for the world economy may be limited as policymakers stay wary at the threat of inflation. Powell’s latest pivot creates a quandary for central bankers around the world.

The IMF inched up its expectations for global economic growth this year, citing strength in the US and some emerging markets, while warning the outlook remains cautious amid persistent inflation and geopolitical risks.

The increasingly hopeful economic story of 2024 so far is that of a world headed for a soft landing. Unfortunately that same world is also becoming more dangerous, divided, indebted and unequal.

US

US retail sales rose by more than forecast in March and the prior month was revised higher, showcasing resilient consumer demand that keeps fueling a surprisingly strong economy. So-called control-group sales — which are used to calculate gross domestic product — jumped by the most since the start of last year.

As President Joe Biden this week hailed America’s booming economy as the strongest in the world during a reelection campaign tour of battleground-state Pennsylvania, global finance chiefs convening in Washington had a different message: cool it. While the world’s largest economy is helping support global growth, it also means the US is “slightly overheated,” the IMF’s Kristalina Georgieva said — thanks in part to Washington’s fiscal stance, with the budget gap pushing toward 7% of GDP.

Emerging Markets

Israel reportedly struck back at Iran on Friday morning, following days of frantic diplomacy from the US and European nations in which they tried to convince Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu not to respond too aggressively, if at all, to the Iranian attack. Their main concern is to avoid a wider war in a region already roiled by the Israel-Hamas conflict and which could send oil prices above $100 a barrel.

India forecast an above-normal monsoon this year, raising optimism that ample rains will spur crop output and economic growth, as well as prompt the government to ease curbs on exports of wheat, rice and sugar. Forecast of a normal monsoon bodes well for easing food costs, and headline consumer price inflation eventually, said Anubhuti Sahay, head of economic research, South Asia, at Standard Chartered Plc.

Europe

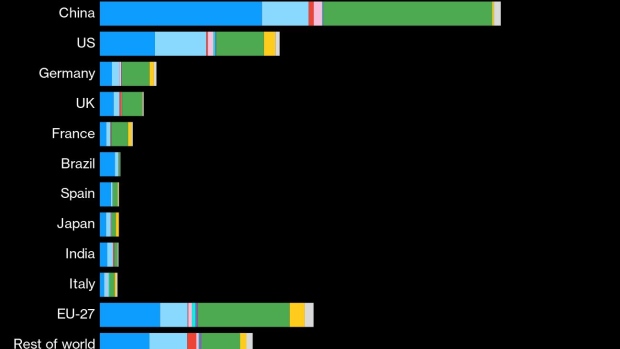

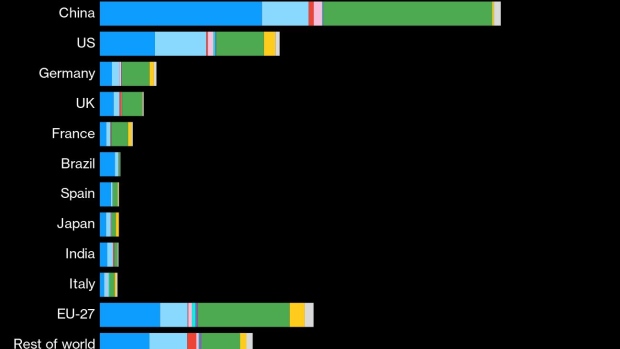

European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen is unleashing a barrage of trade restrictions against China as she seeks to follow through on a pledge to make the EU a more relevant political player on the global stage. It’s in the area of clean tech where the EU is most fervently fighting to stave off competition from cheap Chinese imports of everything from EVs to solar panels.

UK inflation slowed less than expected last month as fuel prices crept higher, prompting traders to further unwind bets on how many interest rate cuts the Bank of England will deliver this year.

Asia

China reported faster-than-expected economic growth in the first quarter – along with some numbers that suggest things are set to get tougher in the rest of the year. Gross domestic product climbed 5.3% in the period, accelerating slightly from the previous quarter and beating estimates. But much of the bounce came in the first two months of the year. In March, growth in retail sales slumped and industrial output fell short of forecasts, suggesting challenges on the horizon.

–With assistance from John Ainger, Irina Anghel, Enda Curran, Shawn Donnan, James Hirai, Rajesh Kumar Singh, John Liu, Lucille Liu, Eric Martin, Alberto Nardelli, Tom Orlik (Economist), Pratik Parija, Zoe Schneeweiss, Craig Stirling and Fran Wang.

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

Economy

Bobby Kennedy And The Ownership Economy – Forbes

In recent decades, populist presidential campaigns have arisen from the left (Bernie Sanders) and the right (Pat Buchanan). Both of these campaigns had limited appeal across the political spectrum or even attempted to engage Americans of diverse political views.

Over the past year in his independent presidential campaign, Bobby Kennedy Jr. has sought to bring together members of both major political parties, with a form of economic populism that expands ownership opportunities. In contrast to Sanders, Kennedy’s goal is not to grow the welfare state or state control over the economy. His economic populism is free-market oriented, aimed at building a broader property-owning middle class. It is aimed at widening the number of worker-owners with a stake in the market system, through their ownership of homes, businesses, employee stock and profit sharing, and other assets.

Whether Kennedy’s economic strategies can achieve the goals of ownership and the middle class he has set, remains to be determined. But his “ownership economy” is one that should be discussed and debated. Currently, it is largely ignored by the legacy media—or subsumed by the parade of articles speculating about of how many votes he will “take away” from President Biden or President Trump.

I wrote about Kennedy’s heterodox jobs program late last summer. In the eight months since, he has sharpened his jobs agenda, and connected it to a broader platform of worker ownership. It is time to revisit the campaign’s economic themes, briefly noting three of the subjects Kennedy often speaks about in 2024: the abandonment of vast sections of the blue collar economy, low wage workforces, and the marginalization of small businesses.

Abandonment Of Blue Collar Economy

“Compensate the losers” is the way that political scientist Ruy Teixeira characterizes the Democratic Party approach to the blue collar economy since the 1990s. According to this approach, workers whose jobs are impacted by environmental policies (oil and gas workers) or trade polices (heavy manufacturing workers) will be retrained for jobs in the green economy or in advanced manufacturing or even as white collar fields like information technology (the oil worker as coder). Since the 1990s a vast network of dislocated worker programs and rapid-response programs have arisen and are prominent under the Biden administration.

As might be expected, retraining hasn’t proved so easy in practice. One example: here in Northern California, the Marathon Oil

MRO

refinery closed in October 2020, laying off 345 workers. The federal and state government immediately came in with the union offering a range of retraining and job placement services. A study by the UC Berkeley Labor Center found that even a year after closure, a quarter of the workers were still unemployed. Those that were employed earned a median of $12 less than their previous jobs. Other studies similarly have identified the gap between theories of skills transference and re-employment and the realities for most blue collar workers—including the realties of alternative energy jobs today that usually pay considerably less than oil and gas jobs.

Each refinery closure or plant closure has its own business dynamics, and in many cases, like the Marathon Oil refinery, the facility will not be able to avoid closing. Re-employment cannot be avoided. Kennedy has spoken of improving the re-training and re-employment process for laid off workers, implementing best practices in retraining with the participation of unions and worker organizations.

function loadConnatixScript(document)

if (!window.cnxel)

window.cnxel = ;

window.cnxel.cmd = [];

var iframe = document.createElement(‘iframe’);

iframe.style.display = ‘none’;

iframe.onload = function()

var iframeDoc = iframe.contentWindow.document;

var script = iframeDoc.createElement(‘script’);

script.src = ‘//cd.elements.video/player.js’ + ‘?cid=’ + ’62cec241-7d09-4462-afc2-f72f8d8ef40a’;

script.setAttribute(‘defer’, ‘1’);

script.setAttribute(‘type’, ‘text/javascript’);

iframeDoc.body.appendChild(script);

;

document.head.appendChild(iframe);

loadConnatixScript(document);

(function()

function createUniqueId()

return ‘xxxxxxxx-xxxx-4xxx-yxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx’.replace(/[xy]/g, function(c) 0x8);

return v.toString(16);

);

const randId = createUniqueId();

document.getElementsByClassName(‘fbs-cnx’)[0].setAttribute(‘id’, randId);

document.getElementById(randId).removeAttribute(‘class’);

(new Image()).src = ‘https://capi.elements.video/tr/si?token=’ + ’44f947fb-a5ce-41f1-a4fc-78dcf31c262a’ + ‘&cid=’ + ’62cec241-7d09-4462-afc2-f72f8d8ef40a’;

cnxel.cmd.push(function ()

cnxel(

playerId: ’44f947fb-a5ce-41f1-a4fc-78dcf31c262a’,

playlistId: ‘4ed6c4ff-975c-4cd3-bd91-c35d2ff54d17’,

).render(randId);

);

)();

Manufacturing jobs as a share of total jobs have been in decline for the past four decades, and even as he urges trade policies for reshoring jobs, Kennedy recognizes that manufacturing going forward will be a limited part of the blue collar economy. The blue collar jobs of the future will increasingly be in the trades and services. Kennedy has enlisted “Dirty Jobs” host Mike Rowe to highlight the importance of the trades, and identify policies that can improve conditions and wages for the trades. Among these policies: a greater share of the higher education federal budget redirected from colleges into training in the trades, and support for the workers who seek to enter and remain in the trades.

Improving the economic position of blue collar workers also means expanding employee stock ownership and profit sharing. While worker cooperatives have failed to gain traction in America, forms of employee stock ownership and profit sharing are being implemented in companies with significant blue collar workforces, such as Procter & Gamble

PG

, Southwest Airlines

LUV

and Chobani. Kennedy poses the challenge: Let’s have workers-as-owners more fully share in the economic success of their employers.

Inflation Impact On Low Wage Workers

In nearly all of his talks on the economy, Kennedy addresses the issue of affordability, and how inflation has undercut wages of America’s lower wage workforces. He posts regularly on the increased cost of food, transportation, and housing, the financial strains on working class and middle class families, the number of workers who live paycheck to paycheck. When the March national jobs report was issued earlier this month, he noted the slowdown in year-over wage growth (at 4.1% the lowest year-over increase since 2021) and the increase in part-time jobs.

Kennedy recognizes that many of the low wage workforces are in such sectors as long-term care, retail, and hospitality, in which profit margins for employers are tight, and employers have limited flexibility individually to raise wages. Kennedy continues his calls for a higher minimum wage, reducing health care costs, strengthening protections and benefits for workers in the gig economy. He urges a reconsideration of trade and tax policies and the need for immigration policies that secure the nation’s borders. Kennedy’s strict border policies reflect both the “humanitarian crisis” he sees with the drug cartels and migrants, as well as the impact of unchecked immigration on the wages of low wage service and production workers.

Home ownership has a special place in Kennedy’s ownership economy, as part of bringing more workers into the middle class, and he has stepped up his advocacy on home ownership. Across society, widespread home ownership stabilizes communities, promotes civic involvement, serves as a hedge against social disorders.

Small And Independent Businesses

During the pandemic, Kennedy warned that economic lockdowns were devastating the small business economy. Today, in a regular series of podcasts on small business, he highlights the ongoing small business struggles. Just this past week, the National Federation of Independent Business, the nation’s largest small business organization, released a survey showing small business optimism is at its lowest level since 2012.

As with home ownership, Kennedy characterizes widespread small business ownership in terms of the social values as well as the values to the individual owners. Small business drives enterprise and service to others, in providing goods and services that customers value and will pay for. It drives job creation, including for individuals who do not fit easily into larger employment venues. A Kennedy Administration will prioritize rebuilding the small business economy, particularly in rural and inner city communities.

Kennedy’s small business agenda goes beyond a laundry list of small business grant and loan programs. As with the wage question, Kennedy seeks to tie a vibrant small business economy to underlying trade and tax policies. He also seeks to tie this economy to reforms in federal government procurement policies, which he describes as ineffectual.

Economic Challenges And Alternatives

The middle class society and economy of the 1950s that Kennedy grew up in and is central to his worldview was the product of unique economic forces and America’s dominant position in the post-World War II period. There is no way to get back to it, and recreating it will be more difficult than in the past, in the now global economy, and with rapidly advancing technologies.

But a broad middle class of worker-owners, is the right goal, and private sector ownership the right approach. People may find Kennedy’s strategies insufficiently detailed or unrealistic or even counterproductive. But Kennedy raises thoughtful challenges and alternatives to the economic platforms of the two main parties—just as he is raising serious challenges on a range of other issues.

Economy

Biden's Hot Economy Stokes Currency Fears for the Rest of World – Bloomberg

As Joe Biden this week hailed America’s booming economy as the strongest in the world during a reelection campaign tour of battleground-state Pennsylvania, global finance chiefs convening in Washington had a different message: cool it.

The push-back from central bank governors and finance ministers gathering for the International Monetary Fund-World Bank spring meetings highlight how the sting from a surging US economy — manifested through high interest rates and a strong dollar — is ricocheting around the world by forcing other currencies lower and complicating plans to bring down borrowing costs.

-

Media22 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Media24 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Investment22 hours ago

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

-

Real eState14 hours ago

Botched home sale costs Winnipeg man his right to sell real estate in Manitoba – CBC.ca

-

News20 hours ago

Canada Child Benefit payment on Friday | CTV News – CTV News Toronto

-

Business22 hours ago

Gas prices see 'largest single-day jump since early 2022': En-Pro International – Yahoo Canada Finance

-

Business14 hours ago

Dow Jones Rises But S&P, Nasdaq Fall; Nvidia, SMCI Flash Sell Signals As Bitcoin's Fourth Halving Arrives – Investor's Business Daily

-

Politics23 hours ago

Politics23 hours agoIran news: Canada, G7 urge de-escalation after Israel strike – CTV News