Nearly 30 years ago, the PBS program Firing Line convened a debate about the War on Drugs, which has contributed more than any other criminal-justice policy to deadly street violence in Black neighborhoods and the police harassment, arrest, and mass incarceration of Black Americans. Revisiting the debate helps clarify what it will take to end that ongoing policy mistake.

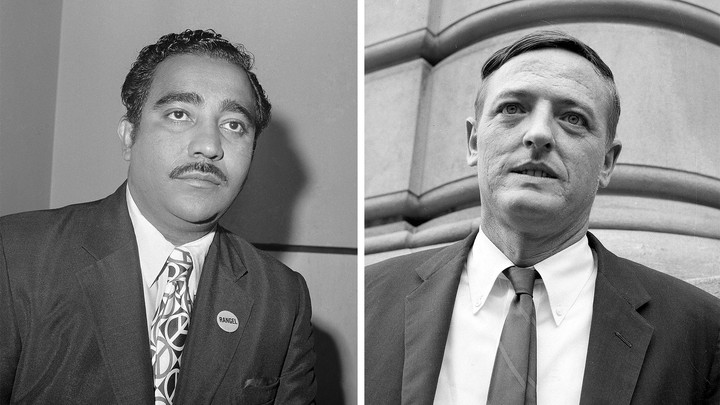

Congressman Charlie Rangel led one side in the 1991 clash. Born in 1930, Rangel served in the Korean War, provided legal assistance to 1960s civil-rights activists, participated in the Selma-to-Montgomery marches, and represented Harlem for 46 years as a Democrat in the House. He was once arrested while participating in an anti-apartheid rally. Opposing him was William F. Buckley Jr., the conservative intellectual who founded National Review in 1955 and took the wrong side in some of the most significant racial-justice controversies of his day. In an infamous 1957 editorial, Buckley justified the imposition of white-supremacist racial segregation in the American South. He opposed federal civil-rights legislation in the 1960s. And he was an apologist for South Africa’s apartheid regime in the 1980s.

Rangel was Black. Buckley was white. Rangel had demonstrated a lifelong commitment to the full equality of Black people. Buckley had repeatedly stood athwart civil-rights advances, yelling “Stop!” Yet on debate night in 1991, the Democratic representative was the one arguing that the arrest and mass incarceration of Americans caught possessing or selling drugs should continue. And the Reaganite conservative was the one insisting that the human costs of a “law and order” approach were too steep to bear, citing roughly 800,000 Americans arrested that year.

“Let’s do what we can for those who are afflicted short of sending them to jail,” Buckley said. “I want to hear from you whether you want a society based on, say, the Malaysian or the Singapore model in which––and I’m not exaggerating––people get publicly flogged and they get hanged and they get their fingers chopped off. Is this what you want to do in order to accomplish your aims?” he asked Rangel. “If not, what is it that you want to do that we’re not doing already?”

Rangel acknowledged that the criminal-justice system “has not worked and has not been a deterrent to drug abuse in this country.” He added, “I still believe that it should be there, because in order to fight this war, you need all of these factors working together. We should not allow people to be able to distribute this poison without fear that maybe they might be arrested and put in jail.” In fact, Rangel clarified, if somebody wants to sell drugs to a child, they should fear “that they will be arrested and go to jail for the rest of their natural life. That’s what I’m talking about when I say fear.” Then he suggested that America should tap the generals who won the Gulf War to intensify the War on Drugs. “What we’re missing: to find a take-charge general like Norman Schwarzkopf, like Colin Powell, to coordinate some type of strategy so that America, who has never run away from a battle, will not be running away from this battle,” he said. “Let’s win this war against drugs the same way we won it in the Middle East.”

What insights can today’s War on Drugs abolitionists take from this story?

First, that in politics and policy making, neither all good nor all bad things go together. A person might care deeply about racial equality, as Rangel did, yet support a policy that fuels racial disparities. A rival might reject anti-racist politics, even siding with white supremacists on some issues, as Buckley did, while fighting to abandon a ruinous policy that has disproportionately harmed generations of Black people. “It is outrageous to live in a society whose laws tolerate sending young people to life in prison because they grew, or distributed, a dozen ounces of marijuana,” Buckley wrote to the New York Bar Association in 1995 as part of his ongoing advocacy. “I would hope that the good offices of your vital profession would mobilize at least to protest such excesses of wartime zeal, the legal equivalent of a My Lai massacre. And perhaps proceed to recommend the legalization of the sale of most drugs, except to minors.” In 1996, National Review joined him, editorializing “that the war on drugs has failed, that it is diverting intelligent energy away from how to deal with the problem of addiction, that it is wasting our resources, and that it is encouraging civil, judicial, and penal procedures associated with police states.”

Conor Friedersdorf: Why the war on cocaine isn’t working

Had the drug war ended back in the early 1990s, younger Millennials would have been spared a policy that empowered gangs, fueled bloody wars for drug territory in American cities, ravaged Latin America, enriched narco cartels, propelled the AIDS epidemic, triggered police militarization, and contributed more than any other policy to racial disparities in national and local incarceration.

Instead, the War on Drugs continues as a bipartisan enterprise even today. And that brings us to a second insight: As in 1991, when Buckley argued on the same side as the ACLU, unexpected alliances are possible. Some proponents of decriminalizing drugs and cutting the DEA budget, such as Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, are in broad alignment with the left-identitarian approach to anti-racism. Other War on Drugs opponents, on the left and the right, reject that approach. For example, my colleague John McWhorter, who has argued that the drug war is “destroying black America,” believes that what he calls “third-wave anti-racism” is a quasi-religious dead end too prone to Manichaean perspectives.

What if all drug-war opponents joined forces, much as Christian conservatives, progressives, and libertarians have united in efforts to reform sentencing rules and reduce mass incarceration?

A majority may want to end the drug war. According to a 2019 Cato Institute poll, 69 percent of Democrats, 54 percent of independents, and 40 percent of Republicans support decriminalizing drugs. But it may take an alliance among people with different motivations, including anti-racism; a mistrust of the state; a principled love of liberty; a desire to do cocaine at parties; a quasi-religious interest in the mind-expanding possibilities of psychedelics; the experience of losing a loved one to impure drugs; and many others. Forging a right-left coalition may be the only way to finally succeed in ending the decades-long debacle.

Read: How the War on Drugs kept black men out of college

Finally, that decades-old debate shows that cooperation among different kinds of drug-war opponents should be easier now than it was in 1991. Conservatives and libertarians today reject white supremacy and racism in ways Buckley and his fellow War on Drugs abolitionist Ron Paul did not. In practice, however, interacting with people on the other side of the culture wars may be more difficult today. Public support for politicians who compromise has fallen as negative polarization has increased. And social media makes it easier to rally people who seek to punish sin and enforce purity. If Buckley were still alive today, could a university get away with platforming him in a debate? The populist-right website The Daily Caller has advocated against the War on Drugs. Would its Trump-loving readers tolerate an alliance with Ocasio-Cortez?

But impure alliances are the path to success. Coalitions drawing from the whole political spectrum can’t coalesce and succeed if, say, drug-war critics on the left won’t work with anyone who flies a Gadsden flag, or drug-war abolitionists on the right won’t work with a member of Congress who says “Black Lives Matter” but won’t say “Blue Lives Matter.” Without progress, innocents such as Breonna Taylor, who was killed in a botched no-knock drug raid in Louisville, Kentucky, will keep dying.

Roughly 450,000 people in the United States are currently incarcerated for drug offenses. “Black Americans are nearly six times more likely to be incarcerated for drug-related offenses than their white counterparts, despite equal substance usage rates,” the Center for American Progress found in 2018. “Almost 80 percent of people serving time for a federal drug offense are black or Latino. In state prisons, people of color make up 60 percent of those serving time for drug charges.” If the War on Drugs ended today, racial disparities in raids, arrests, sentencing, and incarceration would likely shrink, as would adversarial interactions between the police and civilians, and much violence that U.S. drug policy fuels in Mexico, Colombia, and beyond. Cooperating to end the drug war is a moral imperative for the left and the right.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.