OTTAWA — Two years after it was criticized for not issuing an emergency alert during a 13-hour-long killing spree in Nova Scotia, the RCMP finally has a national Alert Ready policy in place.

The eight-page internal policy came into force on March 1 and was provided to The Canadian Press by the RCMP.

It outlines the circumstances in which a public alert can be used, including active shooter situations, terrorist attacks, riots and natural disasters.

Each commanding officer is supposed to establish a public alert coordinator position and keep statistics on the use of alerts.

According to the policy, members collect information about the incident, who is involved — including a description of the person and vehicle, if there is one — where and when it happened, why the alert is being issued and “the actions that the public is expected to take.”

Supervisors or unit commanders approve those requests, and the RCMP says the decision to use an alert is “at the discretion of those officers responding and managing the incident.”

“RCMP policy provides a guide for dealing with incidents but does not direct officers to issue alerts since policy can never address all possible situations,” an RCMP spokesperson said in an email.

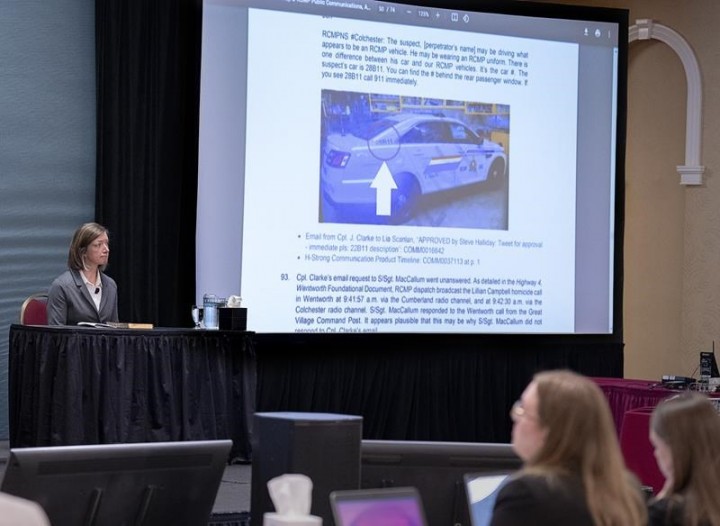

In April 2020 gunman Gabriel Wortman murdered 22 people in Nova Scotia while dressed as a cop and driving a mock police car. The killing spree spanned more than 100 kilometres and more than 13 hours, but the emergency alert system was never activated to warn the public.

The RCMP instead used Twitter to share information.

The force has said it was in the process of drafting an alert when the gunman was killed by police on April 19, but the ongoing public inquiry into the shootings has also revealed that senior officers were not aware of how to use the system.

Family members of the victims have said lives could have been saved had people been notified earlier. The public inquiry has been tasked with investigating the RCMP’s communication with the public during and after that weekend.

Supt. Dustine Rodier, who was in charge of the operational communications centre during the shooting, told the inquiry last week that “Alert Ready would be considered” in an active shooter event now.

Previously released evidence has confirmed senior RCMP officers were worried that a broader public alert could have put officers in danger by causing a “frantic panic.” The Mounties have also suggested that 911 operators could have been overwhelmed by callers seeking information.

Nova Scotia has used the emergency alert system 12 times since the shooting for events involving a police response. Paul Mason, the head of Nova Scotia’s Emergency Management Office, told the inquiry “we have not seen mass panic in response of utilization of the system.”

Cheryl McNeil, a consultant and a former employee of the Toronto police, referred to the theory as the “panic myth,” and said “as long as alerts are clear, concisely stated and provide direction, I don’t see how panic can be an expected outcome of advising the public of information they need to know.”

The RCMP’s national policy says “there will be an increase in calls” after an alert is sent out and that will likely strain resources. It recommends bringing in more staff if possible.

Rodier told the inquiry that the best way to counter that is through public education about emergency alerts, but she also said the RCMP has not developed any public education tools. She said that would be up to the province.

The new policy says it’s up to commanding officers in each division to work with the provincial or territorial authorities to establish public alert protocols, including what to do if the incident moves from one province or territory to another.

The RCMP can now issue its own alerts in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick, thanks to agreements signed with both provinces since the shooting spree.

In 2016, Nova Scotia’s Emergency Management Office offered the RCMP the ability to issue alerts because police have round-the-clock staffing and are “better positioned to respond quickly to unfolding events,” according to a summary of evidence released at the public inquiry.

The offer was not accepted.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published June 17, 2022.

Sarah Ritchie, The Canadian Press