Science

Regular old rock? Think again. Here’s your guide to erratic boulders in Alberta

|

|

If you’re taking a walk just east of Calgary’s Coventry Hills neighbourhood, you may dismiss it as a regular old rock covered in graffiti.

But to Lincoln Friske, it’s a local treasure.

A large erratic boulder sits just past Nose Creek Park. Friske visits the massive rock on his daily dog walks, and he decided recently to create a digital 3D model of it so others could appreciate it, too.

“It’s set up just like an anomaly in the middle of this massive park,” he said in an interview on the Calgary Eyeopener. “Most people didn’t even know there was this graffiti erratic in our own backyard.”

Erratics are stones, boulders or big blocks picked up and moved by glaciers from one place to another during the last ice age.

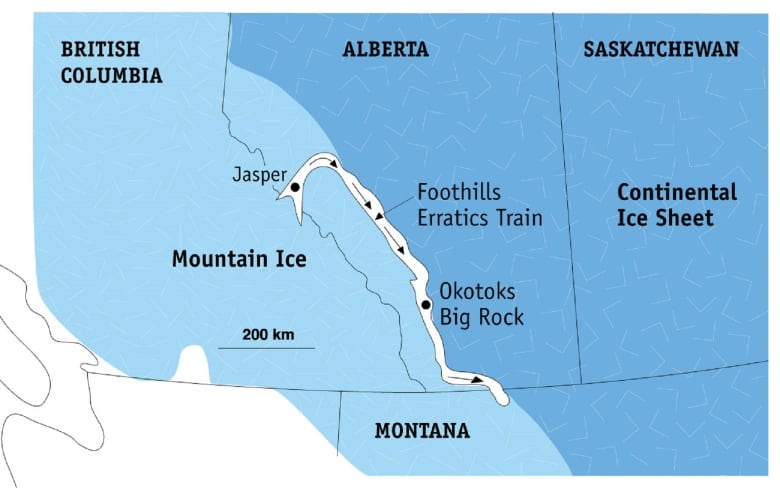

There are thousands dotting the Foothills, part of a 600-kilometre section known as the Foothills Erratics Train. It runs from about Hinton, Alta., all the way down to the Montana border.

Eva Enkelmann, an associate professor in the University of Calgary’s department of geoscience, says the boulders typically look out of place.

“It almost looks like it fell out of the sky. What that means is it doesn’t really match with the rocks you find in that area,” she said.

The stones are typically white, grey or slightly pink.

They’re made of quartzite — or cemented sand grains — dating back some 500 million years, according to Dale Leckie, geologist and author of The Scenic Geology of Alberta: A Roadside Touring And Hiking Guide.

Researchers have traced the material back to Mount Edith Cavell in Jasper National Park, about 300 kilometres northwest of Calgary.

“They are a very distinctive type of rock,” Leckie said.

“You can see features inside them, which geologists call cross-beds. They’re structures from the waves and the tides when they were deposited.”

So how did they get here?

About 20,000 years ago, a landslide occurred in Jasper National Park.

The tumbling boulders fell onto valley glaciers in the Athabasca River valley. They floated north, then east, then bumped into the Laurentide ice sheet, which covered most of Canada at the time, and were redirected southward, Leckie said.

Over time, they became scattered across the Foothills.

“When the ice melted, eventually it just let them down, I’ll say almost gently, onto the landscape, slipping, sliding back and forth,” Leckie said.

Most of the erratic boulders landed in their current resting spots about 16,000 years ago.

Another distinctive feature is how solid the erratics are, Enkelmann said.

“Only rocks that are very, very hard actually survive such a long transport,” she said. “The river would usually round the boulders and eventually they turn into pebbles.”

If you look closely, though, some of the boulders do have some round edges along their lower portions.

That’s because hundreds of years ago, bison used to rub up on the boulders to get rid of their winter coats, Leckie said, creating more polished bits. They also created depressions around the boulders known as buffalo wallows.

Where are they?

You can stumble upon an erratic boulder in many farmers’ fields running along the Rocky Mountains, Leckie said, but some of the rocks have become famous landmarks.

The largest and most well-known example would be the Okotoks erratic — also known as Big Rock — which is about the size of a three-storey apartment building. A 3D model of the erratic is also available courtesy of the University of Calgary.

The province designated Big Rock a provincial historic resource in 1978 to protect its geological and cultural importance.

“I think they’re so interesting because they’re just giant blocks,” Leckie said.

“They really grab your attention … they just jump out in the landscape because they’re standing high almost like sentinels.”

Several notable erratics are located in Calgary, including the one documented near Coventry Hills.

One sits on top of Nose Hill Park. Another, known as Split Rock, is in the city’s northeast, just off Harvest Hills Boulevard and Beddington Trail N.W.

Leckie has seen others in a McKenzie Lake playground and a Tuscany rest area. In Panorama Hills, there’s an erratic — sometimes referred to as crater rock — in a small park.

There are hundreds more, says Enkelmann, and once you’re aware of them, you’ll start to notice them everywhere.

“For me, it’s fascinating that you can weave this whole story by looking at these erratics here in the city, where we are relatively far away from the mountains but we have this evidence,” she said.

Science

Scientists Say They Have Found New Evidence Of An Unknown Planet… – 2oceansvibe News

In the new work, scientists looked at a set of trans-Neptunian objects, or TNOs, which is the technical term for those objects that sit out at the edge of the solar system, beyond Neptune

The new work looked at those objects that have their movement made unstable because they interact with the orbit of Neptune. That instability meant they were harder to understand, so typically astronomers looking at a possible Planet Nine have avoided using them in their analysis.

Researchers instead looked towards those objects and tried to understand their movements. And, Dr Bogytin claimed, the best explanation is that they result from another, undiscovered planet.

The team carried out a host of simulations to understand how those objects’ orbits were affected by a variety of things, including the giant planets around them such as Neptune, the “Galactic tide” that comes from the Milky Way, and passing stars.

The best explanation was from the model that included Planet 9, however, Dr Bogytin said. They noted that there were other explanations for the behaviour of those objects – including the suggestion that other planets once influenced their orbit, but have since been removed – but claim that the theory of Planet 9 remains the best explanation.

A better understanding of the existence or not of Planet 9 will come when the Vera C Rubin Observatory is turned on, the authors note. The observatory is currently being built in Chile, and when it is turned on it will be able to scan the sky to understand the behaviour of those distant objects.

Planet Nine is theorised to have a mass about 10 times that of Earth and orbit about 20 times farther from the Sun on average than Neptune. It may take between 10,000 and 20,000 Earth years to make one full orbit around the Sun.

You may be tempted to ask how an entire planet could ‘hide’ in our solar system when we have zooming capabilities such as the new iPhone 15 has, but consider this: If Earth was the size of a marble, the edge of our solar system would be 11 kilometres away. That’s a lot of space to hide a planet.

[source:independent]

Science

Dragonfly: NASA Just Confirmed The Most Exciting Space Mission Of Your Lifetime – Forbes

NASA has confirmed that its exciting Dragonfly mission, which will fly a drone-like craft around Saturn’s largest moon, Titan, will cost $3.35 billion and launch in July 2028.

Titan is the only other world in the solar system other than Earth that has weather and liquid on the surface. It has an atmosphere, rain, lakes, oceans, shorelines, valleys, mountain ridges, mesas and dunes—and possibly the building blocks of life itself. It’s been described as both a utopia and as deranged because of its weird chemistry.

Set to reach Titan in 2034, the Dragonfly mission will last for two years once its lander arrives on the surface. During the mission, a rotorcraft will fly to a new location every Titan day (16 Earth days) to take samples of the giant moon’s prebiotic chemistry. Here’s what else it will do:

- Search for chemical biosignatures, past or present, from water-based life to that which might use liquid hydrocarbons.

- Investigate the moon’s active methane cycle.

- Explore the prebiotic chemistry in the atmosphere and on the surface.

Spectacular Mission

“Dragonfly is a spectacular science mission with broad community interest, and we are excited to take the next steps on this mission,” said Nicky Fox, associate administrator of the Science Mission Directorate at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “Exploring Titan will push the boundaries of what we can do with rotorcraft outside of Earth.”

It comes in the wake of the Mars Helicopter, nicknamed Ingenuity, which flew 72 times between April 2021 and its final flight in January 2023 despite only being expected to make up to five experimental test flights over 30 days. It just made its final downlink of data this week.

Dense Atmosphere

However, Titan is a completely different environment to Mars. Titan has a dense atmosphere on Titan, which will make buoyancy simple. Gravity on Titan is just 14% of the Earth’s. It sees just 1% of the sunlight received by Earth.

function loadConnatixScript(document)

if (!window.cnxel)

window.cnxel = ;

window.cnxel.cmd = [];

var iframe = document.createElement(‘iframe’);

iframe.style.display = ‘none’;

iframe.onload = function()

var iframeDoc = iframe.contentWindow.document;

var script = iframeDoc.createElement(‘script’);

script.src = ‘//cd.elements.video/player.js’ + ‘?cid=’ + ’62cec241-7d09-4462-afc2-f72f8d8ef40a’;

script.setAttribute(‘defer’, ‘1’);

script.setAttribute(‘type’, ‘text/javascript’);

iframeDoc.body.appendChild(script);

;

document.head.appendChild(iframe);

loadConnatixScript(document);

(function()

function createUniqueId()

return ‘xxxxxxxx-xxxx-4xxx-yxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx’.replace(/[xy]/g, function(c) 0x8);

return v.toString(16);

);

const randId = createUniqueId();

document.getElementsByClassName(‘fbs-cnx’)[0].setAttribute(‘id’, randId);

document.getElementById(randId).removeAttribute(‘class’);

(new Image()).src = ‘https://capi.elements.video/tr/si?token=’ + ’44f947fb-a5ce-41f1-a4fc-78dcf31c262a’ + ‘&cid=’ + ’62cec241-7d09-4462-afc2-f72f8d8ef40a’;

cnxel.cmd.push(function ()

cnxel(

playerId: ’44f947fb-a5ce-41f1-a4fc-78dcf31c262a’,

playlistId: ‘aff7f449-8e5d-4c43-8dca-16dfb7dc05b9’,

).render(randId);

);

)();

The atmosphere is 98% nitrogen and 2% methane. Its seas and lakes are not water but liquid ethane and methane. The latter is gas in Titan’s atmosphere, but on its surface, it exists as a liquid in rain, snow, lakes, and ice on its surface.

COVID-Affected

Dragonfly was a victim of the pandemic. Slated to cost $1 billion when it was selected in 2019, it was meant to launch in 2026 and arrive in 2034 after an eight-year cruise phase. However, after delays due to COVID, NASA decided to compensate for the inevitable delayed launch by funding a heavy-lift launch vehicle to massively shorten the mission’s cruise phase.

The end result is that Dragonfly will take off two years later but arrive on schedule.

Previous Visit

Dragonfly won’t be the first time a robotic probe has visited Titan. As part of NASA’s landmark Cassini mission to Saturn between 2004 and 2017, a small probe called Huygens was despatched into Titan’s clouds on January 14, 2005. The resulting timelapse movie of its 2.5 hours descent—which heralded humanity’s first-ever (and only) views of Titan’s surface—is a must-see for space fans. It landed in an area of rounded blocks of ice, but on the way down, it saw ancient dry shorelines reminiscent of Earth as well as rivers of methane.

The announcement by NASA makes July 2028 a month worth circling for space fans, with a long-duration total solar eclipse set for July 22, 2028, in Australia and New Zealand.

Wishing you clear skies and wide eyes.

Science

Scientists claim evidence of 'Planet 9' in our solar system – Supercar Blondie

A team of scientists claims to have evidence that there is another hidden planet – nicknamed ‘Planet 9’ – lurking in our solar system.

Of course, there have been changes to the number of planets in our solar system over recent – in space terms, anyway – years, as Pluto is no longer considered a proper planet.

Seems a bit harsh, doesn’t it?

However, a team of astronomers now believe that they have the strongest evidence yet that there is another mysterious planet hovering around our sun.

READ MORE! James Webb Telescope observes light on Earth-like planet for the first time in history

The theory that there could be other planets orbiting our star has been around for years, as scientists have noticed some unusual phenomena on the edge of the solar system that suggest the existence of another celestial body.

The theory that another planet is responsible would also explain the orbit of other objects that are outliers in our system, sitting more than 250 times Earth’s distance from the sun.

Scientist Konstantin Bogytin and his team have long been proponents of this ‘Planet 9’ theory, and now they believe they have ‘the strongest statistical evidence yet that Planet 9 is really out there’.

As we know, it wouldn’t be the only strange thing in our solar system.

Perhaps they just need to point a massive space telescope at it and they’ll find evidence of alien life out there.

This new study by Bogytin and his team focused on a number of Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs) that lie outside the orbit of Neptune towards the outer reaches of our solar system.

In analyzing the movements of these objects – which can be affected by the orbit of Neptune, as well as passing stars and the ‘galactic tide’ – the scientists concluded that there could be another unseen planet out there.

Dr Bogytin pointed out that there are other potential explanations for the behavior of these objects, but – he believes – Planet 9 is the best bet.

Once the Vera C. Rubin Observatory in Chile becomes active, we might get the best look we’ve had yet.

In a paper, the team wrote: “This upcoming phase of exploration promises to provide critical insights into the mysteries of our solar system’s outer reaches.”

That paper, entitled ‘Generation of Low-Inclination, Neptune-Crossing TNOs by Planet Nine’ is available to read here.

Images in this article were generated using AI

-

Investment23 hours ago

Investment23 hours agoUK Mulls New Curbs on Outbound Investment Over Security Risks – BNN Bloomberg

-

Sports21 hours ago

Sports21 hours agoAuston Matthews denied 70th goal as depleted Leafs lose last regular-season game – Toronto Sun

-

Media2 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Business20 hours ago

BC short-term rental rules take effect May 1 – CityNews Vancouver

-

Media4 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Art19 hours ago

Collection of First Nations art stolen from Gordon Head home – Times Colonist

-

Investment20 hours ago

Investment20 hours agoBenjamin Bergen: Why would anyone invest in Canada now? – National Post

-

Tech22 hours ago

Tech22 hours agoSave $700 Off This 4K Projector at Amazon While You Still Can – CNET