WASHINGTON — Canadian audiences have grown used to seeing an Indigenous politician denounce the federal legacy of residential schools. For Maka Black Elk, it was nothing short of a revelation.

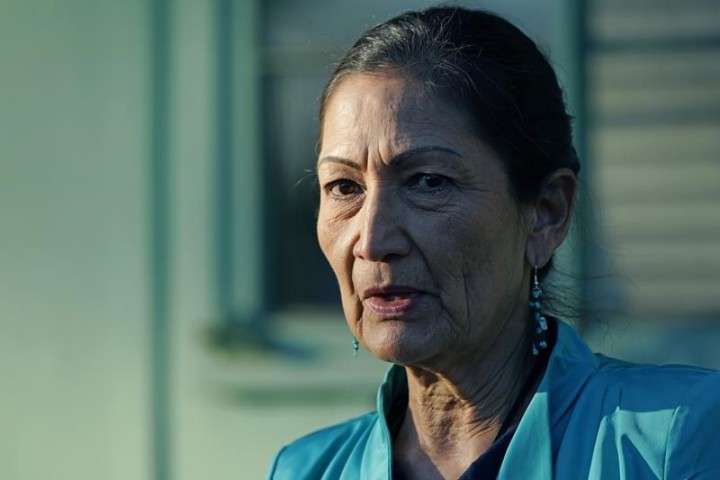

Black Elk watched Wednesday as the first Indigenous cabinet secretary in American history described in chilling detail the 150-year legacy of abuse and neglect at Indian boarding schools, perpetrated in part by the U.S. government.

Investigators found marked and unmarked burial sites at the locations of 53 former Indigenous residential schools in the U.S., and as the work continues, that number will likely grow, said the newly released report.

So too, it predicted, will the number of dead: at least 500 so far, linked to 19 of the 408 schools identified to date as having operated with U.S. government funding in 37 states and then-territories between 1819 and 1969.

Rules were enforced through corporal punishment, including flogging and whipping, solitary confinement, starvation, slapping and cuffing. Older students were at times forced to abuse their younger colleagues.

And in some cases, funding for some schools may have come from money set aside for Indigenous communities that ceded their lands to the U.S.

“The investigation shows that the United States may have used moneys held in Tribal trust accounts, including those based on cessions of Indian territories to the United States, to fund Indian children to attend federal Indian boarding schools.”

With the ultimate goal of eradicating the Indigenous way of life, children were forced to change their names, cut their hair, abandon traditional languages and routinely perform military drills.

Then they were put to work, raising livestock and chickens, making bricks and garments, producing lumber, cooking, helping to build irrigation systems and even U.S. railroads.

By itself, the report commissioned last June by Interior Secretary Deb Haaland likely proved shocking but not surprising to members of Indigenous communities on either side of the Canada-U.S. border.

“This is not new to us,” an emotional Haaland said, gesturing to indicate the other Indigenous officials and guests in the room at the Department of the Interior.

“We have lived with the intergenerational trauma of federal Indian boarding school policies for many years. What is new is the determination in the Biden-Harris administration to make a lasting difference in the impact of this trauma for future generations.”

But for Black Elk, the executive director for truth and healing at the Red Cloud Indian School in Pine Ridge, S.D., Wednesday was “historic and significant” not for what was being said, but who it was saying it, and where.

“The department that was responsible for funding and running the schools has formally acknowledged and named, in a tone that’s really different for a government organization, the history, their role in the trauma, and the legacy,” he said, fighting tears.

“Because there’s an Indigenous person and multiple Indigenous people at the helm of that institution, who all have a deep personal connection to the history, as we all do, this has happened in the way it has happened.”

Haaland herself acknowledged the significance of Wednesday’s spectacle.

“I come from ancestors who endured the horrors of the Indian boarding school assimilation policies carried out by the same department that I now lead,” she said.

“Now, we are uniquely positioned to assist in the effort to recover the dark history of these institutions that have haunted our families for too long.”

Haaland ordered the Indian Boarding School Initiative last June, an early executive decision that came just days after a B.C. First Nation announced the grim discovery of human remains at a former residential school.

Its initial report — what came out Wednesday was only Volume 1, and was accompanied by the oft-repeated message that a great deal more work remains — comes not long after Canada’s own residential-school reckoning reached a remarkable climax last month.

“I want to say to you with all my heart: I am very sorry,” Pope Francis told Indigenous delegates from Canada during a meeting at the Vatican, a long-sought gesture of reconciliation for the generations of harm done at schools run by the Roman Catholic Church.

In Canada, an estimated 150,000 Indigenous children are believed to have attended one of about 150 residential schools that operated between the 1880s and when the last one closed in 1996.

Marc Miller, Canada’s minister of Crown-Indigenous relations, said he consulted with Haaland last fall, who has already acknowledged the importance of the grim discoveries in Canada as a significant catalyst in her own work.

Miller said there has been “cross-pollination” between the two departments in recent months on the issue of residential schools, especially given that the border between the two countries is largely an artifice for Indigenous communities.

Miller acknowledged the “change in tone and approach” in the U.S. under President Joe Biden, and cheered Haaland on in her efforts.

“I often hear from Indigenous communities, particularly those that are along the border, about these issues, and they’re very present,” he said. “They’re very real, and it’s a lived experience of Indigenous Peoples across the Americas.”

Black Elk said it’s unlikely that the residential school situation in the U.S. would have received any fresh scrutiny without the “rediscovery” of human remains at unmarked burial sites near several former residential schools in Canada.

A number of such discoveries have been made in the last year since ground-penetrating radar located what are believed to be more than 200 graves at a former residential school in Kamloops, B.C., last spring.

“Without them, I don’t know if this would have gotten the attention it got here in the United States,” said Black Elk.

“It’s this kind of moment that reignites this issue in the minds of the public, and that’s both good and unfortunate. But confrontation of this challenging history is what we need to help move our nation and our community forward.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published May 11, 2022.

James McCarten, The Canadian Press