Science

Russia to send new Soyuz capsule after tiny meteoroid cripples ISS one

|

|

Russia said on Wednesday it would launch another Soyuz spacecraft next month to bring home two of its own cosmonauts and a US astronaut from the International Space Station after their original capsule was struck by a micrometeoroid and started leaking.

The last month’s leak came from a tiny puncture — less than 1 millimetre wide — on the external cooling system of the Soyuz MS-22 capsule, one of two return capsules docked to the ISS that can bring crew members home.

“Having analysed the condition of the spacecraft, thermal calculations and technical documentation, it has been concluded that the MS-22 must be landed without a crew on board,” said Yuri Borisov, the head of the Russian space agency Roscosmos.

Russia said a new capsule, Soyuz MS-23, would be sent up on 20 February from the Baikonur cosmodrome in Kazakhstan to replace the damaged Soyuz MS-22, which will be returned to Earth empty. The new capsule will have to fly to the ISS in autopilot mode, too.

The original plan was to launch the MS-23 in March with two Russians and one American, replacing the three already up there. This new crew will now have to wait until late summer or fall to fly when another capsule is ready for them.

The crew is ‘safe on board the space station’, NASA says

Russian cosmonauts Sergey Prokopyev and Dmitry Petelin and US astronaut Francisco Rubio had been due to end their mission in March but will now extend it by a few more months and return aboard the MS-23.

“They are ready to go with whatever decision we give them,” Joel Montalbano, NASA’s ISS program manager, told a news conference. “I may have to fly some more ice cream to reward them,” he added.

If there is an emergency in the meantime, Roscosmos said it would look at whether the MS-22 spacecraft can be used to rescue the crew. In this scenario, temperatures in the capsule could reach unhealthy levels of 30-40 degrees Celsius.

“In case of an emergency, when the crew will have a real threat to life on the station, then probably the danger of staying on the station can be higher than going down in an unhealthy Soyuz,” Sergei Krikalev, Russia’s chief of crewed space programs, said.

NASA took part in all the discussions and agreed with the plan.

“Right now, the crew is safe on board the space station,” said NASA’s space station program manager Joel Montalbano. “There’s no immediate need for the crew to come home today.”

There are a total of seven space station residents, and the crew can not rely on the MS-22 if they encounter another emergency, like a fire or decompression.

Besides Prokopyev, Petelin and Rubio, the space station is home to NASA astronauts Nicole Mann and Josh Cassada, Russia’s Anna Kikina and Japan’s Koichi Wakata, who rode up on a SpaceX capsule last October.

NASA said it was looking at the possibility of adding extra crew to the capsule — the only other “lifeboat” vehicle currently docked at the station.

‘We are prepared for this situation’, Roscosmos says

The incident has disrupted Russia’s ISS activities, forcing its cosmonauts to call off spacewalks as officials focused on the leaky capsule.

Both NASA and Roscosmos believe the leak was caused by a micrometeoroid — a small particle of space rock — hitting the capsule at high velocity.

“Space is not a safe place, and not a safe environment. We have meteorites, we have a vacuum and we have a high temperature and we have complicated hardware that can fail,” Krikalev said.

“Now we are facing one of the scenarios … we are prepared for this situation.”

The issue comes during the 11th month of Russia’s war against Ukraine, which sparked the biggest crisis in relations between Moscow and the West since the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis.

Moscow has used its space program since the February invasion to show support for its troops.

The Soyuz rocket launched in March 2022 was decked out with a large letter “Z”, known as the main symbol of Russia’s aggression against its neighbour.

In early July of 2022, cosmonauts Oleg Artemyev, Denis Matveyev and Sergey Korsakov shared photos of themselves aboard the ISS holding the flags of the so-called “people’s republics” of Donetsk Luhansk, two territories in Ukraine’s Donbas that Russia has since unilaterally annexed despite protests by the international community.

On 21 December, Roscosmos’ former director and a close ally of Russian President Vladimir Putin, Dmitry Rogozin, was critically wounded while celebrating his birthday in Moscow-occupied Donetsk.

Rogozin, who was replaced at the helm of Russia’s national space agency on 16 July 2022, is known as one of the most fervent supporters of the war in Ukraine.

The new chief, Yuri Borisov, previously said that Russia plans to pull out of the ISS programme in 2024 and build its own space station down the line.

Neither Roscosmos nor NASA made any comments regarding the ongoing tensions between Moscow and Washington in the context of the Soyuz crisis.

Science

West Antarctica's ice sheet was smaller thousands of years ago – here's why this matters today – The Conversation

As the climate warms and Antarctica’s glaciers and ice sheets melt, the resulting rise in sea level has the potential to displace hundreds of millions of people around the world by the end of this century.

A key uncertainty in how much and how fast the seas will rise lies in whether currently “stable” parts of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet can become “unstable”.

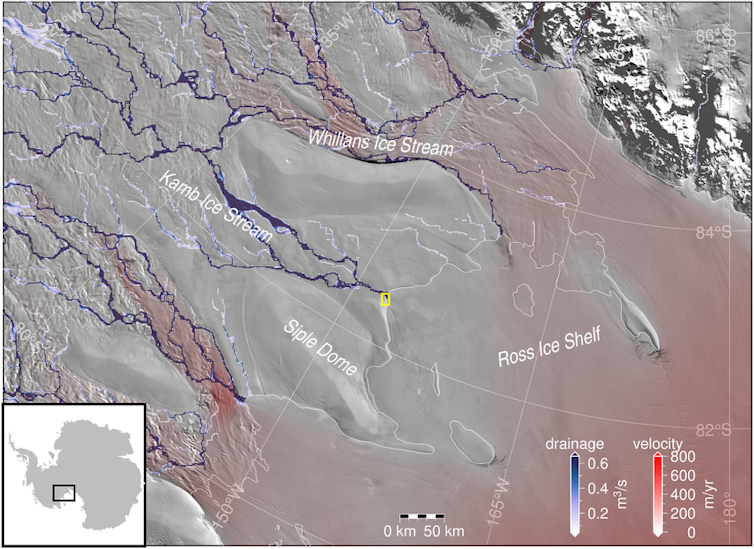

One such region is West Antarctica’s Siple Coast, where rivers of ice flow off the continent and drain into the ocean.

Journal of Geophysical Research, CC BY-SA

This ice flow is slowed down by the Ross Ice Shelf, a floating mass of ice nearly the size of Spain, which holds back the land-based ice. Compared to other ice shelves in West Antarctica, the Ross Ice Shelf has little melting at its base because the ocean below it is very cold.

Although this region has been stable during the past few decades, recent research suggest this was not always the case. Radiocarbon dating of sediments from beneath the ice sheet tells us that it retreated hundreds of kilometres some 7,000 years ago, and then advanced again to its present position within the last 2,000 years.

Figuring out why this happened can help us better predict how the ice sheet will change in the future. In our new research, we test two main hypotheses.

Read more:

What an ocean hidden under Antarctic ice reveals about our planet’s future climate

Testing scenarios

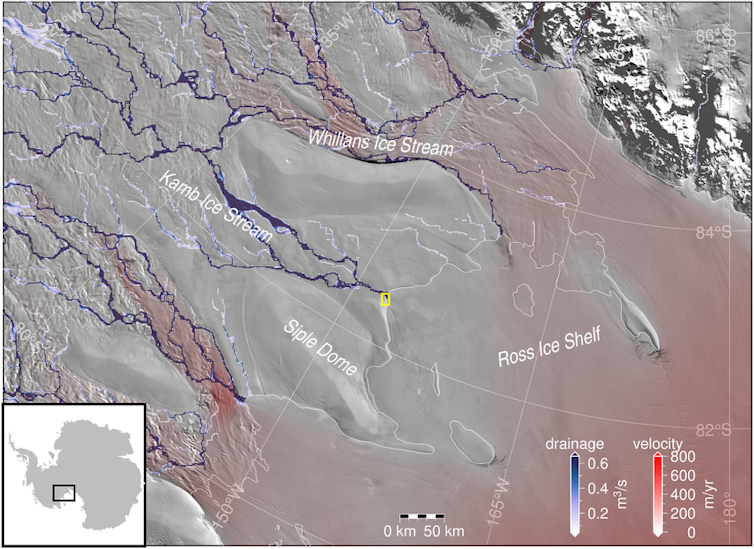

Scientists have considered two possible explanations for this past ice sheet retreat and advance. The first is related to Earth’s crust below the ice sheet.

As an ice sheet shrinks, the change in ice mass causes the Earth’s crust to slowly uplift in response. At the same time, and counterintuitively, the sea level drops near the ice because of a weakening of the gravitational attraction between the ice sheet and the ocean water.

As the ice sheet thinned and retreated since the last ice age, crustal uplift and the fall in sea level in the region may have re-grounded floating ice, causing ice sheet advance.

AGU, CC BY-SA

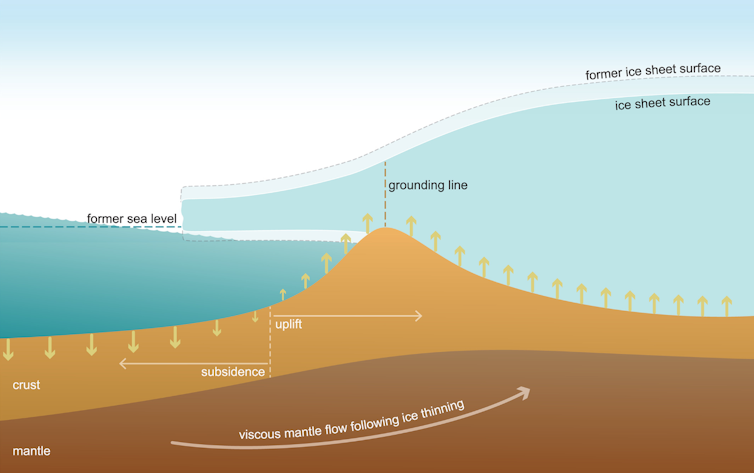

The other hypothesis is that the ice sheet behaviour may be due to changes in the ocean. When the surface of the ocean freezes, forming sea ice, it expels salt into the water layers below. This cold briny water is heavier and mixes deep into the ocean, including under the Ross Ice Shelf. This blocks warm ocean currents from melting the ice.

AGU, CC BY-SA

Seafloor sediments and ice cores tell us that this deep mixing was weaker in the past when the ice sheet was retreating. This means that warm ocean currents may have flowed underneath the ice shelf and melted the ice. Mixing increased when the ice sheet was advancing.

We test these two ideas with computer model simulations of ice sheet flow and Earth’s crustal and sea surface responses to changes in the ice sheet with varying ocean temperature.

Because the rate of crustal uplift depends on the viscosity (stickiness) of the underlying mantle, we ran simulations within ranges estimated for West Antarctica. A stickier mantle means slower crustal uplift as the ice sheet thins.

The simulations that best matched geological records had a stickier mantle and a warmer ocean as the ice sheet retreated. In these simulations, the ice sheet retreats more quickly as the ocean warms.

When the ocean cools, the simulated ice sheet readvances to its present-day position. This means that changes in ocean temperature best explain the past ice sheet behaviour, but the rate of crustal uplift also affects how sensitive the ice sheet is to the ocean.

Veronika Meduna, CC BY-SA

What this means for climate policy today

Much attention has been paid to recent studies that show glacial melting may be irreversible in some parts of West Antarctica, such as the Amundsen Sea embayment.

In the context of such studies, policy debates hinge on whether we should focus on adapting to rising seas rather than cutting greenhouse gas emissions. If the ice sheet is already melting, are we too late for mitigation?

Our study suggests it is premature to give up on mitigation.

Global climate models run under high-emissions scenarios show less sea ice formation and deep ocean mixing. This could lead to the same cold-to-warm ocean switch that caused extensive ice sheet retreat thousands of years ago.

For West Antarctica’s Siple Coast, it is better if we prevent this ocean warming from occurring in the first place, which is still possible if we choose a low-emissions future.

Science

NASA's Voyager 1 resumes sending engineering updates to Earth – Phys.org

For the first time since November, NASA’s Voyager 1 spacecraft is returning usable data about the health and status of its onboard engineering systems. The next step is to enable the spacecraft to begin returning science data again. The probe and its twin, Voyager 2, are the only spacecraft to ever fly in interstellar space (the space between stars).

Voyager 1 stopped sending readable science and engineering data back to Earth on Nov. 14, 2023, even though mission controllers could tell the spacecraft was still receiving their commands and otherwise operating normally. In March, the Voyager engineering team at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California confirmed that the issue was tied to one of the spacecraft’s three onboard computers, called the flight data subsystem (FDS). The FDS is responsible for packaging the science and engineering data before it’s sent to Earth.

The team discovered that a single chip responsible for storing a portion of the FDS memory—including some of the FDS computer’s software code—isn’t working. The loss of that code rendered the science and engineering data unusable. Unable to repair the chip, the team decided to place the affected code elsewhere in the FDS memory. But no single location is large enough to hold the section of code in its entirety.

So they devised a plan to divide affected the code into sections and store those sections in different places in the FDS. To make this plan work, they also needed to adjust those code sections to ensure, for example, that they all still function as a whole. Any references to the location of that code in other parts of the FDS memory needed to be updated as well.

The team started by singling out the code responsible for packaging the spacecraft’s engineering data. They sent it to its new location in the FDS memory on April 18. A radio signal takes about 22.5 hours to reach Voyager 1, which is over 15 billion miles (24 billion kilometers) from Earth, and another 22.5 hours for a signal to come back to Earth. When the mission flight team heard back from the spacecraft on April 20, they saw that the modification had worked: For the first time in five months, they have been able to check the health and status of the spacecraft.

During the coming weeks, the team will relocate and adjust the other affected portions of the FDS software. These include the portions that will start returning science data.

Voyager 2 continues to operate normally. Launched over 46 years ago, the twin Voyager spacecraft are the longest-running and most distant spacecraft in history. Before the start of their interstellar exploration, both probes flew by Saturn and Jupiter, and Voyager 2 flew by Uranus and Neptune.

Provided by

NASA

Citation:

NASA’s Voyager 1 resumes sending engineering updates to Earth (2024, April 22)

retrieved 22 April 2024

from https://phys.org/news/2024-04-nasa-voyager-resumes-earth.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Science

Osoyoos commuters invited to celebrate Earth Day with the Leg Day challenge – Oliver/Osoyoos News – Castanet.net

Osoyoos commuters can celebrate Earth Day as the Town joins in on a national commuter challenge known as “Leg Day,” entering a chance to win sustainable transportation prizes.

The challenge, from Earth Day Canada, is to record 10 sustainable commutes taken without a car.

“Cars are one of the biggest contributors to gas emissions in Canada,” reads an Earth Day Canada statement. “That’s why, Earth Day Canada is launching the national Earth Day is Leg Day Challenge.”

So far, over 42.000 people have participated in the Leg Day challenge.

Participants could win an iGo electric bike, public transportation for a year, or a gym membership.

The Town of Osoyoos put out a message Monday promoting joining the national program.

For more information on the Leg Day challenge click here.

-

Business16 hours ago

Honda to build electric vehicles and battery plant in Ontario, sources say – Global News

-

Science16 hours ago

Science16 hours agoWill We Know if TRAPPIST-1e has Life? – Universe Today

-

Investment20 hours ago

Down 80%, Is Carnival Stock a Once-in-a-Generation Investment Opportunity?

-

Health13 hours ago

Health13 hours agoSee how chicken farmers are trying to stop the spread of bird flu – Fox 46 Charlotte

-

Health16 hours ago

Health16 hours agoSimcoe-Muskoka health unit urges residents to get immunized

-

Science22 hours ago

Science22 hours agoWatch The World’s First Flying Canoe Take Off

-

News21 hours ago

Honda expected to announce multi-billion dollar deal to assemble EVs in Ontario

-

Investment14 hours ago

Investment14 hours agoOwn a cottage or investment property? Here's how to navigate the new capital gains tax changes – The Globe and Mail