Art

Saskatchewan boy, philanthropist, international art dealer

|

|

Like many who grew up in rural Saskatchewan during the 1950s, Frederick Mulder curled, played hockey and golfed in people’s backyards. Looking back now on his childhood in the tiny town of Eston, there was just one indication of the unconventional career he had waiting.

“My ex-wife used to say, ‘You used to go door to door selling Christmas cards, now you just go city to city selling prints.'”

Not just any prints but Picassos, Munches and Matisses.

Mulder, 76, is one of the world’s foremost experts in the field of 19th- and 20th-century European prints. He has sold art to private dealers and museums around the world.

As he walks around the Picasso and Paper exhibit at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, his faint British accent is a reminder that the man has been in England now for over 50 years.

“This is it. This is the one we sold,” said Mulder. “This is a linocut from 1962 of Jacqueline, his wife.”

Mulder graduated from the University of Saskatchewan with a BA in English then attended Brown University in Rhode Island on a scholarship but made a last-minute switch to philosophy. His thesis adviser suggested he write his dissertation at Oxford or Cambridge.

“I thought that was a lovely idea,” Mulder says with a smile.

Borrowing to buy Picassos

With the help of a generous Canada Council fellowship, Mulder hopped on a plane bound for England with a book about investments. The last chapter focused on a man who collected the etchings of 17th-century master Rembrandt van Rijn.

Upon arriving, Mulder attended an auction containing one of the artist’s prints. With little experience in purchasing art, he picked up the phone to seek advice — and ended up dialling the famous Sotheby’s auction house.

“I treated London just like it was, as if it was this small town, really. I thought I could call anybody up or go and see anyone.”

Mulder bought his first Rembrandt print in 1966 and was instantly hooked.

He later sold it and used some of the money to go to Paris. It was there he met up with a man named Paul Proute whose stock included Picassos, including an impression of The Circus — the only Picasso Mulder owned.

“I said to him, well, I’d like to buy yours. And he said, ‘I have a whole bunch of them if, you know, if you want more than one.'”

Mulder bought eight. But had to borrow the money to do it.

“I came back, told my bank that I had done this and said, ‘I hear you have these things called overdrafts,'” he says with a laugh. “The bank manager was amused. I don’t think he’d ever had a graduate student asking if he could, you know, borrow money to buy some Picassos.”

Within two weeks, he says, he’d sold every Picasso for double what he’d paid.

It was the start of a formula that propelled Mulder’s career forward: buy strategically, sell honestly, profit slowly. Eventually, the art would go for as much as $3 million.

Despite his success, Mulder never aspired to own a yacht or go on expensive vacations. In fact, his 20-year-old Volkswagen was stolen a few years ago so now he rides a bicycle or uses Uber to get around.

Instead, Mulder uses that money to give back.

Passionate philanthropist

“Fred’s passions go far beyond the art world, and I would divide them into two that are connected at the hip,” said University of Saskatchewan president Peter Stoicheff, who has known Mulder for eight years. “One is philanthropy … and the other is … in environmental causes.”

Mulder estimates, and media reports confirm, he has so far donated around 10 million pounds (more than $17 million Cdn) to various causes. He says the environment is definitely a focus.

“I think that what we’re doing now is we’re stealing the future from our children. We don’t have the right to use resources that we should be leaving for you to use,” said Mulder.

“He’s very humble,” said Stoicheff. “It’s difficult to say exactly where that comes from, but part of it is that he grew up in small-town Saskatchewan.”

There are now Picasso works splashed across the Prairies — nearly all with ties to Mulder, and at least six of which he donated to the University of Saskatchewan (U of S).

In 2012, Mulder sold what he calls “the most extensive collection of Picasso linocuts in the world” to Ellen Remai. She subsequently donated it to the Remai Modern, a Saskatoon art museum named after her, and that sparked a partnership between the museum and the U of S.

The collection is valued at some $20 million.

Back to his roots

In May, Mulder will return to his home province for a Picasso symposium put on by the museum and the U of S, which in 2017 honoured Mulder for his “lifelong contributions in the art world and his passion for philanthropy.”

“It’ll be nice to go back,” said Mulder. “I’ve often thought if I had come from the same background in the U.K. that I came from in Saskatchewan, which is a very remote farming town, I probably would have had the wrong accent, the wrong set of ideas.”

Asked what his younger self would think upon hearing about the life he has lived, Mulder says with a laugh, “I would have thought that they must be talking about somebody else.”

There was no art in Eston, Sask., when Mulder grew up. There is now, however, one Picasso linocut, donated by Mulder, that hangs in the local museum, a testament to where the great art dealer is from, where he went and the endless possibilities of where anyone can go.

“These things happen. They could so easily not have happened,” said Mulder, “and if you take the opportunity that they provide, you know, they kind of transform your life.”

Art

The Wall Street lawyer who quit to make Lego art: ‘It is a job, not a hobby’ – The Guardian

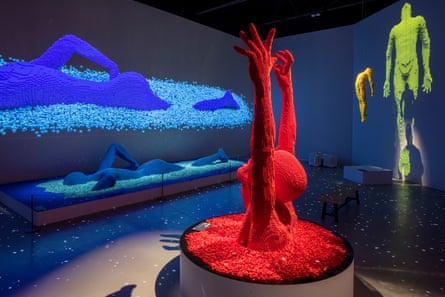

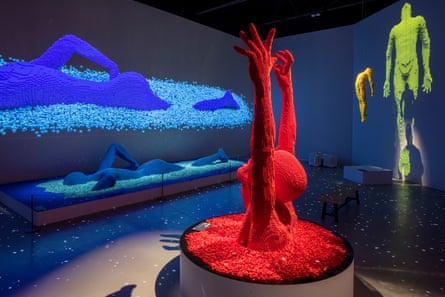

He’s made a living out of building sculptures from Lego and his work has been shown in 100 cities and 24 countries, attracting millions of visitors. But you won’t find any Lego in Nathan Sawaya’s home. Call it work-life balance: “I love what I do, but it is a job … not a hobby,” the 50-year-old American artist says.

It is a job, but it’s also something like a dream. Sawaya was a Wall Street lawyer who was unhappy with his career, playing with his favourite childhood toys after hours to unwind. Creating elaborate sculptures from scratch wasn’t unfamiliar to him – as a child, when his parents wouldn’t buy him a dog, he fashioned a lifesize pet from Lego bricks. “It was very rudimentary, but it was what I could do as a kid,” he recalls.

Sawaya began posting photos of his sculptures online. When his website crashed from all the clicks, he took it as a sign to quit law and pursue Lego. The first iteration of Sawaya’s travelling exhibition, the Art of the Brick, was held at a small art museum in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 2007, featuring about two dozen sculptures. “I treated it like a wedding and invited all my friends and family from all over,” he says. “I expected that to be my last solo show, but fortunately it has kept going ever since.”

Initially, Sawaya was met with resistance from Lego – the company’s first ever contact was a cease and desist. But he eventually went to work for Lego as a master model builder (the people who build the models for Legoland and other official operations). The audition process sounds simple enough, but it requires skill. “They say: here’s a pile of bricks, build a sphere out of it. You build the sphere and they roll it across the table or the floor to see how you did.”

After a short stint with Lego, Sawaya branched out on his own. He’s now a Lego certified professional, a title reserved for those who have made their own businesses from the bricks. “It’s a very good business relationship,” Sawaya says of his dealings with Lego these days. He has to buy the bricks, like anyone else. “I understand that they’re a toy company, and they understand that I’m an artist.”

Is there any tension in making art from a branded product? “Of course,” he says. “I’m subject to the decisions of a third party.” For example, he’s limited to the colours that Lego produces – he gets around this by having an extensive inventory of about 10m bricks between his two studios in Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

Sawaya doesn’t see his exhibition as promotional for Lego – “I don’t call the show the art of Lego,” he points out – but he acknowledges that the accessibility that makes him love the medium so much also equates to something of a monopoly. “It is still a brand, and that is a part of it,” he says. “When you get up very close to every sculpture of mine, you can see the word Lego on every individual piece.”

The Art of the Brick, which has just opened in Melbourne, has been a worldwide hit – there are three or four exhibitions running simultaneously at any given time. “They’re all different, but there are favourites that I’ve replicated because there’s some expectation that certain pieces are going to be there,” he says.

Sawaya’s most well-known piece is 2007’s Yellow, a sculpture of a man opening his own chest to reveal Lego pieces spilling out – Lady Gaga superimposed her head on to it in the video for her 2014 single G.U.Y. At the Melbourne show it looms large, surrounded by seven smaller-scale versions in different colours.

But there are plenty more. Sawaya doesn’t keep count of how many sculptures he’s created over the past two decades, but estimates that it might be close to a thousand. He’s made a six-metre-long Batmobile and a lifesize replica of Central Perk, the cafe from Friends, with fellow Lego artist Brandon Griffith, which required 1m bricks.

So what goes into planning a Lego sculpture on this level? “It depends on the piece, of course, but it all starts with the idea,” he says. “There’s some mapping that goes into it – sometimes it’s just drawing it out. Sometimes it’s digital.

“There’s also a lot of research that goes into it: am I doing a piece that people are familiar with? If it’s a replica – let’s say an art history piece – that’s going to require going and looking at the original, gathering photographs and whatnot. If it’s just pouring out of my brain, then it’s more trial and error.”

In Melbourne, Sawaya’s works are animated with kinetics for the first time – 250 glowing skulls move in mesmerising waves against a mirrored wall, with lights and music adding a new dimension. In another room, there’s a lit-up recreation of Formula One driver Lando Norris’s helmet at an 18:1 ratio; in yet another, realistic animals, including a giraffe and a polar bear mother and cub, are projected against their natural habitats in a collaboration with the Australian photographer Dean West.

These creations are undeniably impressive, but peer into some corners of the internet and you’ll find some people asking: is it art? In Sawaya’s mind, at least, it doesn’t matter. “I leave it up to the art critics and students to decide what the art world thinks,” he says. “I’m not striving for it – I’m just doing my own thing.”

-

The Art of the Brick is on now at Melbourne Showgrounds.

Art

Faith Ringgold Perfectly Captured the Pitch of America's Madness – The New York Times

Faith Ringgold, who died Saturday at 93, was an artist of protean inventiveness. Painter, sculptor, weaver, performer, writer and social justice activist, she made work in which the personal and political were tightly bonded. And much of that work gained popularity among audiences that didn’t necessarily frequent galleries and museums. This was particularly true of her series of semi-autobiographical painted narrative quilts depicting scenes of African American urban childhood, subject matter that translated readily into illustrated children’s books, of which, over the years, Ringgold published many.

Altogether, hers added up to a landmark-status career. But the art establishment, as defined by major museums, big-bucks auction houses and a few talent-hogging galleries, never knew quite what to do with it, or with her. So they didn’t do anything. No mega-surveys, no million-dollar corporate commissions, no Venice Biennale-type canonizations.

Recently, though, very late in the day, came a serious uptick in attention. In 2016, the Museum of Modern Art finally brought Ringgold into its collection with the acquisition of several pieces from early in her career. One of them was a monumental 1967 painting titled “American People Series #20: Die.” It shows a crowd of panicked men, women and children, white and Black, screaming and bleeding, and stampeding in all directions as if under lethal attack from some unseen force.

It’s useful to remember where Ringgold stood in her life at the time she painted the picture. Harlem-born, she’d had a classical art education, was teaching art in public school, and was painting what she herself described as Impressionist-style landscapes. She was also reading James Baldwin, listening to the news, and seeing American racial politics shift from civil rights-era passive resistance to a newly assertive Black power. The country was on red alert, just as it is today, and her art responded to the emergency by turning topical.

In the paintings she called the “American People Series,” of which “Die” was one, white people and Black people appear together, but with skewed power balances made clear. In an early picture, “The Civil Rights Triangle” from 1963, five men in business suits, four Black, one white, form a pyramid, with the white man on top, indicating that to the extent the civil rights movement was white-approved, it was also white-controlled.

In “Die,” the culminating picture in the series, a full-on war has erupted, though one that goes beyond being a clear-cut race war. All the figures in the picture look equally stunned and traumatized by the blood bath they find themselves in.

And for Ringgold at this time, art itself went beyond being the seismic recorder of a culture. It also became a vehicle for path-clearing and ethical advocacy. She organized protests against the exclusion of Black artists from leading museums, and designed posters in support of the Attica inmates and the activist Angela Davis. In a painting series called “Black Light,” she eliminated white pigment from her palette and mixed black into all her colors. By the 1970s she had become convinced that Black liberation and women’s liberation were inseparable causes. In 1971 she painted a mural for what was then the Women’s House of Detention on Rikers Island.

She knew that the country she lived in was actively, murderously crazy. For an artist to find a voice for that craziness, to get the pitch of the madness right, was unusual and daring. For that artist to be Black and female was more than unusual, and met with pushback from many sources, most of them within the art world itself.

The kind of painting she favored — figurative, storytelling, polemical — was out of fashion with the establishment, which well into the ’60s touted abstraction as the only “serious” aesthetic mode. (Even within Black art circles a debate over whether modern art, Black or otherwise, should admit political content was very much alive.) And her work continued to run against the grain throughout the Minimalist and Conceptualist years. It’s only recently, with figurative painting hugely in vogue, that her work has gained something like market currency.

And over the decades she continued to develop in new directions. Her formal means grew ever more craft-intensive, incorporating weaving, sewing and carving. Her political content drew less from the news and more from art history and her own life. Her determination to share this content, often determinedly Black-positive in tone, with young audiences through 20 published children’s books is all but unique in contemporary art annals.

The full range of these developments was on display in an overdue retrospective, “Faith Ringgold: American People,” organized by the New Museum in 2022. But back to Ringgold at MoMA in 2019.

For the opening of its newly expanded premises, the museum was rehanging, top to bottom, its permanent collection galleries, and “Die,” a relatively recent arrival, was chosen for inclusion. More than that, it was awarded a starring role. It shared an otherwise sparsely installed gallery with a major MoMA attraction, Picasso’s 1907 “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” a confrontational image of five nude Catalan prostitutes with sliced-up bodies and faces like African masks.

The two paintings were placed cater-corner in the gallery, so you could take them in together at a glance. Both are violent. (The colonialist implications of “Demoiselles” have been much noted, and art historians have read the picture as, among other things, an expression of male sex panic.) Both register as scorchingly political, while leaving their precise politics unclear. Paired at MoMA, they seemed to be visually and conceptually duking it out.

For me, Ringgold — an avowed Picasso fan — won the match. But what really mattered was simply that she was there, smack in the center of Western Modernism’s ground zero institution, and with her most radical image. I admire Ringgold’s later art, much of it materially innovative and expressively buoyant. But it’s the early work, from the pivotal period that produced “Die,” that I keep coming back to.

What she managed to do, in those early paintings, was put aside all the conventional art tools she’d been schooled with, beauty among them (she would later reclaim it), in order to face down the world as it really was, including an art world that had no use for her — a Black woman — and was, in fact, fortressed to keep her and everyone like her out.

Certain artists manage to leap over walls. Picasso was one. And some tunnel under those walls, hit resistance, tunnel some more and, once inside, open a door to let others in. That’s what Faith Ringgold, artist-activist to the end, did.

Art

AI art is only a threat if we let "prompt-jockeys" take control – Creative Bloq

One of the questions that arises in my mind is how we can make generative AI art an actual meaningful creative tool that does our bidding, instead of doing its own thing. The ‘slot machine’ effect is very widespread in generative AI tools, and very rarely do you get anything out that resembles the image you had in your mind as you were going in.

I believe generative AI art tools can be an ally for artists, helping us improve workflows, find new ideas and speed up creativity. The generic nature of AI art can work in our favour, as text prompts alone really can’t replace the imagination of artists. This gets to the very heart of what AI means for creativity, and how we manage its use.

-

Media16 hours ago

Trump Media plunges amid plan to issue more shares. It's lost $7 billion in value since its peak. – CBS News

-

Media24 hours ago

Trump Media stock slides again to bring it nearly 60% below its peak as euphoria fades – National Post

-

Business24 hours ago

Tesla May Be Headed For Massive Layoffs As Woes Mount: Reports – InsideEVs

-

Tech20 hours ago

Tech20 hours agoJava News Roundup: JobRunr 7.0, Introducing the Commonhaus Foundation, Payara Platform, Devnexus – InfoQ.com

-

Real eState19 hours ago

Real estate mogul concerned how Americans will deal with squatters: ‘Something really bad is going to happen’ – Fox Business

-

Sports19 hours ago

Sports19 hours agoRafael Nadal confirms he’s ready for Barcelona: ‘I’m going to give my all’ – ATP Tour

-

Sports24 hours ago

Sports24 hours agoPoints and payouts: Scottie Scheffler cements FedExCup top spot with Masters win, earns $3.6M – PGA TOUR – PGA TOUR

-

Science19 hours ago

Total solar eclipse: Continent watches in wonder – Yahoo News Canada