Health

Science seeking Alzheimer’s clues from few who escape genetic fate

|

|

Doug Whitney inherited the same gene mutation that gave Alzheimer’s disease to his mother, brother and generations of other relatives by the unusually young age of 50.

Yet he’s a healthy 73, his mind still sharp. Somehow, the Washington man escaped his genetic fate.

So did a woman in Colombia who dodged her own family’s similar Alzheimer’s destiny for nearly three decades.

To scientists, these rare “escapees” didn’t just get lucky. They offer an unprecedented opportunity to learn how the body may naturally resist Alzheimer’s.

“It’s unique individuals oftentimes that really provide us with breakthroughs,” said Dr. Eric McDade of Washington University in St. Louis, where Whitney’s DNA is being scoured for answers.

The hope: If researchers could uncover and mimic whatever protects these escapees, they might develop better treatments — even preventive therapies — not only for families plagued by inherited Alzheimer’s but for everyone.

“We are just learning about this approach to the disease,” said neuropsychologist Yakeel Quiroz of Massachusetts General Hospital, who helped study the Colombian woman. “One person can actually change the world — as in her case, how much we have learned from her.”

Quiroz’s team has a pretty good idea what protected Aliria Piedrahita de Villegas — an additional genetic oddity that apparently countered the damage from her family Alzheimer’s mutation. But testing showed Whitney doesn’t have that protective factor so something else must be shielding his brain.

Now scientists are on the lookout for even more Alzheimer’s escapees — people who may have simply assumed they didn’t inherit their family’s mutation because they’re healthy long after the age their loved ones always get sick.

“They just think it’s kind of luck of the draw and it may in fact be that they’re resilient,” said McDade, a researcher with a Washington University network that tracks about 600 members of multiple affected families — including Whitney, the escapee.

“I guess that made me pretty special. And they started poking and prodding and doing extra testing on me,” the Port Orchard, Washington, man said. “I told them, you know, I’m here for whatever you need.”

Answers can’t come quickly enough for Whitney’s son Brian, who also inherited the devastating family gene. He’s reached the fateful age of 50 without symptoms but knows that’s no guarantee.

“I liken my genetics to being a murder mystery,” said Brian Whitney, who volunteers for Washington University studies that include testing an experimental preventive drug. “Our literal bodies of evidence are what they need to crack the case.”

*****

More than 6 million Americans, and an estimated 55 million people worldwide, have Alzheimer’s. Simply getting older is the main risk — it’s usually a disease of people over age 65.

Less than 1% of Alzheimer’s is caused by inheriting a single copy of a particular mutated gene. Children of an affected parent have a 50-50 chance of inheriting the family Alzheimer’s gene. If they do, they’re almost guaranteed to get sick at about the same age as their parent did.

That near certainty allows scientists to study these families and learn critical information about how Alzheimer’s forms. It’s now clear that silent changes occur in the brain at least two decades before the first symptoms — a potential window to intervene. Among the culprits, sticky amyloid starts building up, followed by neuron-killing tau tangles.

What happens instead in the brains of the resilient?

“That’s why I’m here,” said Doug Whitney, who for years has given samples of blood and spinal fluid and undergone brain scans and cognitive exams, in the hunt for clues. “It’s so important that people in my situation come forward.”

Whitney’s grandparents had 14 children and 10 of them developed early-onset Alzheimer’s. The first red flag for his mother: Thanksgiving 1971, when she forgot the pumpkin pie recipe she’d always made from memory.

“Five years later she was gone,”’ Whitney said.

Back then doctors didn’t know much about Alzheimer’s. It wasn’t until the 1990s that separate research teams proved three different genes, when mutated, can each cause this uniquely inherited form of the disease. They each speed abnormal amyloid buildup.

Doug Whitney’s family could only watch and worry as his 50th birthday came and went. His older brother had started showing symptoms at 48. (Some other siblings later were tested and didn’t inherit the gene although two still don’t know.)

“We went through about 10 years when the kids would call home their first question was, ‘How’s Dad?’” his wife Ione Whitney recalled. “By the time he turned 60 we kind of went, wow, we beat the coin toss.”

But not the way he’d hoped. In 2010, urged by a cousin, Whitney joined the St. Louis research. He also agreed to a genetic test he’d expected to provide final reassurance that his children wouldn’t face the same worry — only to learn he’d inherited the family mutation after all.

“He kind of got leveled by that result,” Brian Whitney said.

While Brian inherited the family gene, his sister Karen didn’t — but she, too, is part of the same study, in the healthy comparison group.

*****

U.S. researchers aren’t the only ones on the trail of answers. In South America, scientists are tracking a huge extended family in Colombia that shares a similar Alzheimer’s-causing variant. Carriers of this mutated gene start showing memory problems in their early 40s.

In contrast, one family member — Piedrahita de Villegas — was deemed to have “extreme resistance,” with no cognitive symptoms until her 70s. Researchers flew the woman to Quiroz’s lab in Boston for brain scans. And when she died at 77 of melanoma with only mild signs of dementia, her brain was donated to Colombia’s University of Antioquia for closer examination.

Her brain was jampacked with Alzheimer’s trademark amyloid plaques. But researchers found very little tau — and weirdly, it wasn’t in the brain’s memory hub but in a very different region.

Clearly something affected how tau formed and where. “The thing that we don’t know for sure is why,” Quiroz said.

DNA offered a suspect: An ultra-rare mutation on an unrelated gene.

That APOE gene comes in different varieties, including a version notorious for raising people’s risk of traditional old-age Alzheimer’s and another that’s linked to lower risk. Normally the APOE3 version that Piedrahita de Villegas carried makes no difference for dementia.

But remarkably, both copies of her APOE3 gene were altered by the rare “Christchurch” mutation — and researchers think that blocked toxic tau.

To start proving it, Quiroz’s team used preserved cells from Piedrahita de Villegas and another Colombian patient to grow some cerebral tissue in lab dishes. Cells given the Christchurch mutation developed less tau.

“We still have more work to do but we’re getting closer to understanding the mechanism,” Quiroz said.

That research already has implications for a field that’s long considered fighting amyloid the key step to treating Alzheimer’s.

Instead, maybe “we just need to block what’s downstream of it,” said Dr. Richard Hodes, director of the National Institute on Aging.

And since Whitney, the Washington man, doesn’t have that extra mutation, “there may be multiple pathways for escape,” Hodes added.

In St. Louis, researchers are checking out another clue: Maybe something special about Whitney’s immune system is protecting his brain.

The findings also are fueling a search for more escapees to compare. The Washington University team recently began studying one who’s unrelated to Whitney. In Colombia, Quiroz said researchers are looking into a few more possible escapees.

*****

That search for answers isn’t just work for scientists. Whitney’s son Brian estimates he spends about 25 days each year undergoing different health checks and procedures, many of them far from his Manson, Washington, home, as part of Alzheimer’s research.

That includes every two weeks, getting hooked up to a pump that administers an experimental amyloid-fighting drug. He also gets regular brain scans to check for side effects.

Living with the uncertainty is tough, and he sometimes has nightmares about Alzheimer’s. He tries to follow what he now knows was his parents’ mantra: “Make the best of life till 50 and anything after that is a bonus.”

He makes lots of time to go fishing and camping with daughter Emily, now 12, who hasn’t yet been told about the family gene. He hopes there will be some answers by the time she’s an adult and can consider testing.

“When I have a bad day and decide maybe I should not continue (the research), I think of her and then that all vanishes,” he said.

—Lauran Neergaard, The Associated Press

Health

April 22nd to 30th is Immunization Awareness Week – Oldies 107.7

<!–

isIE8 = true;

Date.now = Date.now || function() return +new Date; ;

Health

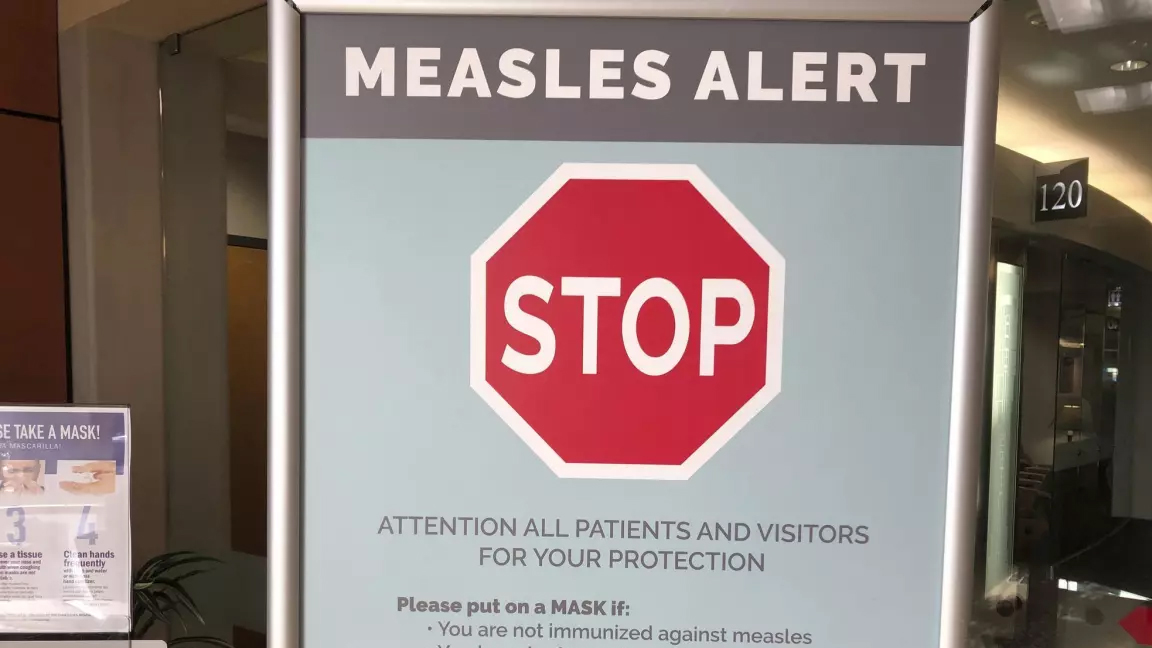

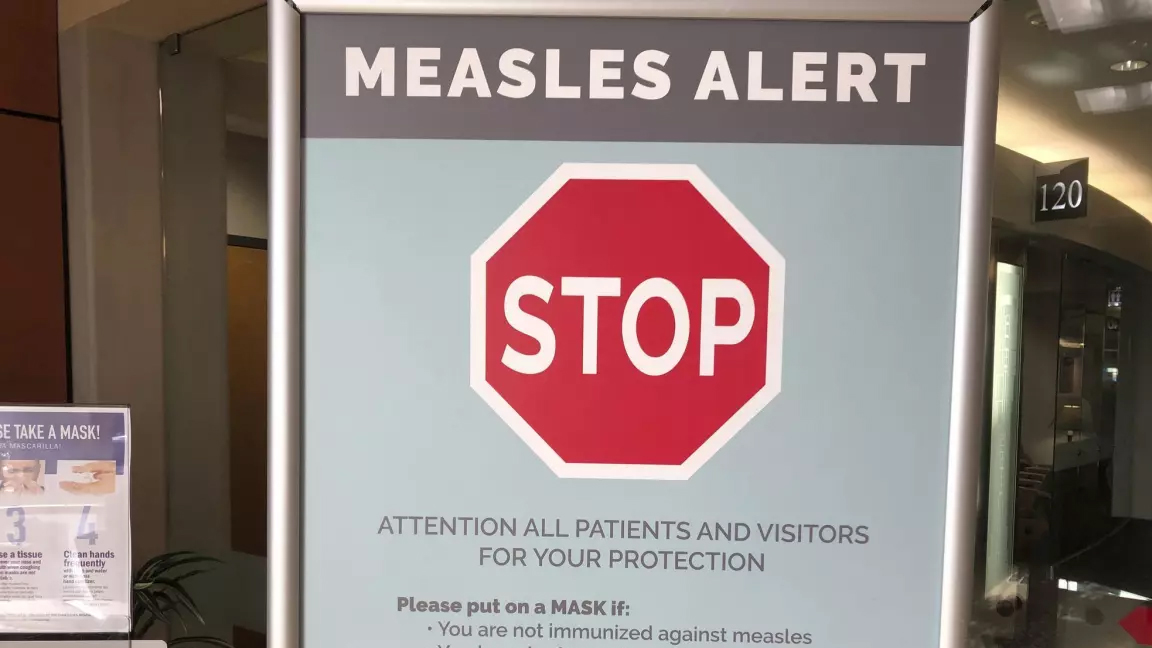

AHS confirms case of measles in Edmonton – CityNews Edmonton

Alberta Health Services (AHS) has confirmed a case of measles in Edmonton, and is advising the public that the individual was out in public while infectious.

Measles is an extremely contagious disease that is spread easily through the air, and can only be prevented through immunization.

AHS says individuals who were in the following locations during the specified dates and times, may have been exposed to measles.

- April 16

- Edmonton International Airport, international arrivals and baggage claim area — between 3:20 p.m. and 6 p.m.

- April 20

- Stollery Children’s Hospital Emergency Department — between 5 a.m. to 3 p.m.

- April 22

- 66th Medical Clinic (13635 66 St NW Edmonton) — between 12:15 p.m. to 3:30 p.m.

- Pharmacy 66 (13637 66 St NW Edmonton) — between 12:15 p.m. to 3:30 p.m.

- April 23

- Stollery Children’s Hospital Emergency Department — between 4:40 a.m. to 9:33 a.m.

AHS says anyone who attended those locations during those times is at risk of developing measles if they’ve not had two documented doses of measles-containing vaccine.

Those who have not had two doses, who are pregnant, under one year of age, or have a weakened immune system are at greatest risk of getting measles and should contact Health Link at 1-877-720-0707.

Symptoms

Symptoms of measles include a fever of 38.3° C or higher, cough, runny nose, and/or red eyes, a red blotchy rash that appears three to seven days after fever starts, beginning behind the ears and on the face and spreading down the body and then to the arms and legs.

If you have any of these symptoms stay home and call Health Link.

In Alberta, measles vaccine is offered, free of charge, through Alberta’s publicly funded immunization program. Children in Alberta typically receive their first dose of measles vaccine at 12 months of age, and their second dose at 18 months of age.

Health

U.S. tightens rules for dairy cows a day after bird flu virus fragments found in pasteurized milk samples – Toronto Star

/* OOVVUU Targeting */

const path = ‘/news/canada’;

const siteName = ‘thestar.com’;

let domain = ‘thestar.com’;

if (siteName === ‘thestar.com’)

domain = ‘thestar.com’;

else if (siteName === ‘niagarafallsreview.ca’)

domain = ‘niagara_falls_review’;

else if (siteName === ‘stcatharinesstandard.ca’)

domain = ‘st_catharines_standard’;

else if (siteName === ‘thepeterboroughexaminer.com’)

domain = ‘the_peterborough_examiner’;

else if (siteName === ‘therecord.com’)

domain = ‘the_record’;

else if (siteName === ‘thespec.com’)

domain = ‘the_spec’;

else if (siteName === ‘wellandtribune.ca’)

domain = ‘welland_tribune’;

else if (siteName === ‘bramptonguardian.com’)

domain = ‘brampton_guardian’;

else if (siteName === ‘caledonenterprise.com’)

domain = ‘caledon_enterprise’;

else if (siteName === ‘cambridgetimes.ca’)

domain = ‘cambridge_times’;

else if (siteName === ‘durhamregion.com’)

domain = ‘durham_region’;

else if (siteName === ‘guelphmercury.com’)

domain = ‘guelph_mercury’;

else if (siteName === ‘insidehalton.com’)

domain = ‘inside_halton’;

else if (siteName === ‘insideottawavalley.com’)

domain = ‘inside_ottawa_valley’;

else if (siteName === ‘mississauga.com’)

domain = ‘mississauga’;

else if (siteName === ‘muskokaregion.com’)

domain = ‘muskoka_region’;

else if (siteName === ‘newhamburgindependent.ca’)

domain = ‘new_hamburg_independent’;

else if (siteName === ‘niagarathisweek.com’)

domain = ‘niagara_this_week’;

else if (siteName === ‘northbaynipissing.com’)

domain = ‘north_bay_nipissing’;

else if (siteName === ‘northumberlandnews.com’)

domain = ‘northumberland_news’;

else if (siteName === ‘orangeville.com’)

domain = ‘orangeville’;

else if (siteName === ‘ourwindsor.ca’)

domain = ‘our_windsor’;

else if (siteName === ‘parrysound.com’)

domain = ‘parrysound’;

else if (siteName === ‘simcoe.com’)

domain = ‘simcoe’;

else if (siteName === ‘theifp.ca’)

domain = ‘the_ifp’;

else if (siteName === ‘waterloochronicle.ca’)

domain = ‘waterloo_chronicle’;

else if (siteName === ‘yorkregion.com’)

domain = ‘york_region’;

let sectionTag = ”;

try

if (domain === ‘thestar.com’ && path.indexOf(‘wires/’) = 0)

sectionTag = ‘/business’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/autos’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/autos’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/entertainment’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/entertainment’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/life’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/life’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/news’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/news’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/politics’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/politics’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/sports’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/sports’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/opinion’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/opinion’;

} catch (ex)

const descriptionUrl = ‘window.location.href’;

const vid = ‘mediainfo.reference_id’;

const cmsId = ‘2665777’;

let url = `https://pubads.g.doubleclick.net/gampad/ads?iu=/58580620/$domain/video/oovvuu$sectionTag&description_url=$descriptionUrl&vid=$vid&cmsid=$cmsId&tfcd=0&npa=0&sz=640×480&ad_rule=0&gdfp_req=1&output=vast&unviewed_position_start=1&env=vp&impl=s&correlator=`;

url = url.split(‘ ‘).join(”);

window.oovvuuReplacementAdServerURL = url;

Infected cows were already prohibited from being transported out of state, but that was based on the physical characteristics of the milk, which looks curdled when a cow is infected, or a cow has decreased lactation or low appetite, both symptoms of infection.

function buildUserSwitchAccountsForm()

var form = document.getElementById(‘user-local-logout-form-switch-accounts’);

if (form) return;

// build form with javascript since having a form element here breaks the payment modal.

var switchForm = document.createElement(‘form’);

switchForm.setAttribute(‘id’,’user-local-logout-form-switch-accounts’);

switchForm.setAttribute(‘method’,’post’);

switchForm.setAttribute(‘action’,’https://www.thestar.com/tncms/auth/logout/?return=https://www.thestar.com/users/login/?referer_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.thestar.com%2Fnews%2Fcanada%2Fu-s-tightens-rules-for-dairy-cows-a-day-after-bird-flu-virus-fragments-found%2Farticle_985b0bac-0252-11ef-abc6-eb884d6a1f0c.html’);

switchForm.setAttribute(‘style’,’display:none;’);

var refUrl = document.createElement(‘input’); //input element, text

refUrl.setAttribute(‘type’,’hidden’);

refUrl.setAttribute(‘name’,’referer_url’);

refUrl.setAttribute(‘value’,’https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/u-s-tightens-rules-for-dairy-cows-a-day-after-bird-flu-virus-fragments-found/article_985b0bac-0252-11ef-abc6-eb884d6a1f0c.html’);

var submit = document.createElement(‘input’);

submit.setAttribute(‘type’,’submit’);

submit.setAttribute(‘name’,’logout’);

submit.setAttribute(‘value’,’Logout’);

switchForm.appendChild(refUrl);

switchForm.appendChild(submit);

document.getElementsByTagName(‘body’)[0].appendChild(switchForm);

function handleUserSwitchAccounts()

window.sessionStorage.removeItem(‘bd-viafoura-oidc’); // clear viafoura JWT token

// logout user before sending them to login page via return url

document.getElementById(‘user-local-logout-form-switch-accounts’).submit();

return false;

buildUserSwitchAccountsForm();

console.log(‘=====> bRemoveLastParagraph: ‘,0);

-

News23 hours ago

Amid concerns over ‘collateral damage’ Trudeau, Freeland defend capital gains tax change

-

Art20 hours ago

The unmissable events taking place during London’s Digital Art Week

-

Politics24 hours ago

Politics24 hours agoPolitics Briefing: Saskatchewan residents to get carbon rebates despite province’s opposition to pricing program

-

News22 hours ago

What is a halal mortgage? How interest-free home financing works in Canada

-

Politics15 hours ago

Politics15 hours agoOpinion: Fear the politicization of pensions, no matter the politician

-

Economy21 hours ago

German Business Outlook Hits One-Year High as Economy Heals

-

Media14 hours ago

B.C. puts online harms bill on hold after agreement with social media companies

-

Politics14 hours ago

Politics14 hours agoPecker’s Trump Trial Testimony Is a Lesson in Power Politics