There’s something really weird in the center of the Milky Way.

The vicinity of a supermassive black hole is a pretty weird place to start with, but in 2020 astronomers found six objects orbiting Sagittarius A* that are unlike anything in the galaxy. They are so peculiar that they have been assigned a brand-new class – what astronomers are calling G objects.

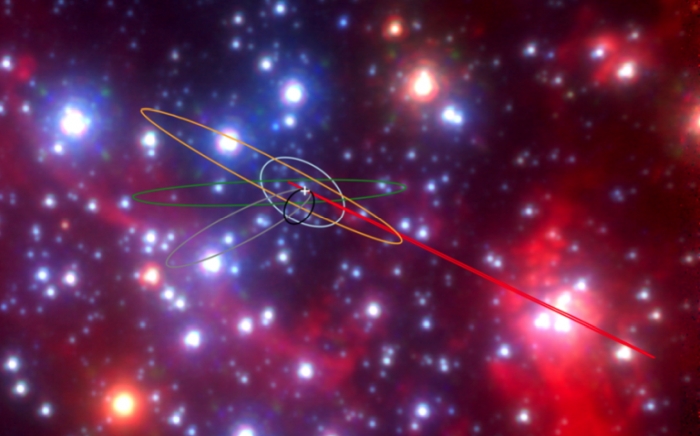

The original two objects – named G1 and G2 – first caught the eye of astronomers nearly two decades ago, with their orbits and odd natures gradually pieced together over subsequent years. They seemed to be giant gas clouds 100 astronomical units across, stretching out longer when they got close to the black hole, with gas and dust emission spectra.

But G1 and G2 weren’t behaving like gas clouds.

“These objects look like gas but behave like stars,” physicist and astronomer Andrea Ghez of the University of California, Los Angeles explained in 2020.

Ghez and her colleagues had been studying the galactic center for over 20 years. Based on that data, a team of astronomers led by UCLA astronomer Anna Ciurlo identified four more of these objects: G3, G4, G5, and G6.

(Anna Ciurlo/Tuan Do/UCLA Galactic Center Group)

They’re on wildly different orbits from G1 and G2 (pictured above); all together, the G objects have orbital periods that range from 170 years to 1,600 years.

It’s unclear exactly what they are, but G2’s intact emergence from periapsis in 2014 – that is, the closest point in its orbit to the black hole – was, Ghez believes, a big clue.

“At the time of closest approach, G2 had a really strange signature,” she said.

“We had seen it before, but it didn’t look too peculiar until it got close to the black hole and became elongated, and much of its gas was torn apart. It went from being a pretty innocuous object when it was far from the black hole to one that was really stretched out and distorted at its closest approach and lost its outer shell, and now it’s getting more compact again.”

Previously, it had been thought that G2 was a cloud of hydrogen gas, which was going to get torn apart and slurped up by by Sgr A*, producing some supermassive black hole accretion fireworks. The fact that nothing happened was later referred to as a “cosmic fizzle“.

The astronomers believe that the answer lies in massive binary stars. Most of the time, these twin stars, locked in a mutual orbit, hang out just doing their buddy star thing. But sometimes – just like colliding binary black holes – they can smoosh into each other, forming one big star.

When this happens, they produce a vast cloud of dust and gas that surrounds the new star for about a million years after the collision.

“Something must have kept [G2] compact and enabled it to survive its encounter with the black hole,” Ciurlo added. “This is evidence for a stellar object inside G2.”

So what of the other five? Well, they could be binary star mergers too. Most of the stars in the galactic center are very massive, and most of them are binaries. And the extreme gravitational forces at play around Sgr A* could be enough to destabilise their binary orbits with relative frequency.

“Mergers of stars may be happening in the Universe more often than we thought, and likely are quite common,” Ghez said.

” Black holes may be driving binary stars to merge. It’s possible that many of the stars we’ve been watching and not understanding may be the end product of mergers that are calm now. We are learning how galaxies and black holes evolve. The way binary stars interact with each other and with the black hole is very different from how single stars interact with other single stars and with the black hole.”

It does seem like the G objects have a lot in common, whatever they are, and expanding the dataset can only provide more information to tease out the puzzle. There is, however, still a lot to figure out. Like some mysterious fireworks spotted flaring out of Sgr A* that’s also been spotted.

Was that a delayed reaction from G2’s periapsis? Was the cosmic fizzle not so fizzly after all? We might just have to keep watching this weird little supermassive black hole corner of space to see what happens next…

The research was published in Nature.

An earlier version of this article was published in December 2020.