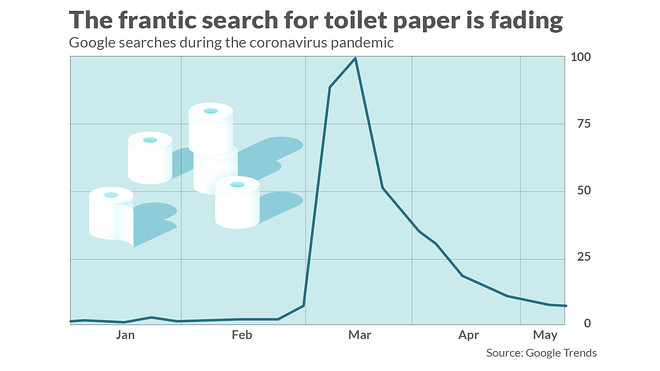

If the end of the great toilet paper shortage is any indication, the U.S. economy has already bottomed out and a fragile recovery is underway.

After months of being hard to find, toilet paper is increasingly available on supermarket shelves and at popular online sites such as Amazon. Americans aren’t hoarding supplies as much or desperately seeking where to find rolls except in a diminishing number of coronavirus hotspots.

Toilet paper is not the only cue.

All 50 states have partly reopened their economies, people are slowly returning to work, consumer confidence has crept higher and Americans are driving further and getting out of their house more often, according to social mobility trackers. Signs of revival are everywhere.

“The economy has bottomed,” said Steve Blitz, chief economist of TS Lombard.

See:MarketWatch Coronavirus Recovery Tracker

The big unknown — what’s on everyone’s mind — is how quickly the U.S. recovers from the shock of a coronavirus pandemic that ignited the fastest and deepest economic slump in modern history. The Wall Street forecasting firm IHS Markit predicts gross domestic product in the second quarter will sink by a whopping 40% at an annualized pace, dwarfing anything the U.S. has witnessed before.

There’s little doubt among economists the U.S. will experience a burst of growth before the end of the year. Blitz likened the economy to a rubber duck being held under water in a bathtub. When it’s released, it briefly shoots up in the air — before falling back down.

That’s the most likely path of the recovery, analysts say. The U.S. will get a pop after most of the coronavirus restrictions are lifted, but the economy won’t be restored to pre-crisis levels for at least a few years.

The biggest barrier naturally is the virus itself. So long as a vaccine or treatment remains elusive, many Americans are likely to continue social distancing and avoiding large crowds on their own volition. Although the vast majority of people who have contracted the virus have survived, a recent poll by Harris Interactive found that 50% of Americans think they will die if they get COVID-19.

“A full recovery in the economy is going to hinge on how well society gets the pandemic under control,” said Boston Federal Reserve President Eric Rosengren. “If consumers are afraid to eat out, shop, travel, a relaxation of laws may do little to bring back customers and thus jobs.”

Read:There’s a limit on what the Fed can do to help, Rosengren says in MarketWatch interview

Absent a cure, large and critical segments of economy will require sweeping changes just to survive that could result in the loss of millions of jobs. These industries include airlines, hotels, retail stores and restaurants.

The restaurant-booking site OpenTable, for example, predicts one in four restaurants are likely to close because of the virus. And airlines that typically bank on selling at least 80% of their seats to make money will have to cut flights, amenities, and jobs if only 60% of their seats are filled in a post-pandemic world. Those are just a few of the nightmare scenarios.

See:TSA passenger travel totals

For now millions of workers in these fields are on furlough and getting paid unemployment benefits by the government. Others who work for idled small businesses have been put back on company payrolls through an emergency federal program that provides forgivable loans.

Yet if these job losses turn from temporary to permanent it will make a recovery all the harder, keeping unemployment in the double digits at least until 2021.

The jobless rate rose unofficially to almost 20% in May, according to a government analysis, from just 3.5% three months ago. More than 20 million people lost their jobs in April alone.

Read:Great Depression 2020? The unofficial U.S. jobless rate is at least 20%—or worse

Feeling growing public pressure and worried about falling tax revenue, every state is reopening their economies ore relaxing restrictions to try to limit the damage

“The longer stay-in-place restrictions prevail, the more likely job losses are permanent rather than temporary,” said economist Stephen Gallagher of Societe Generale.

There’s growing evidence that federal help is working for small business and state reopenings. The number of Americans in early May who were collecting unemployment benefits, known as continuing claims, actually fell for the first time since the crisis began.

“The much slower rise in continuing claims suggests that people are now beginning to return to work,” chief U.S. economist Paul Ashworth of Capital Economics said.

The Trump White House, with an eye toward the 2020 presidential elections, is pushing the states to reopen even faster. Yet most economy watchers, including Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, suggest Washington will have to spend even more than the $3 trillion it has already approved.

“This is the biggest shock we’ve seen in living memory. The question that looms in the air is, is it enough?” Powell told senators at a hearing on Tuesday about emergency loans for business.

The next pivotal event for the economy is likely to come by midsummer when federal programs that offer extra unemployment benefits and subsidies to keep small business workers on payrolls expire. If not enough workers are able to return to their jobs because business is slow, Congress might need to add more money to the pot to prevent more mass layoffs and another shock to the economy.

Local and state governments are also coping with unprecedented declines in tax revenue and are being forced to lay off scores of workers. Democrats and Republicans are divided over whether to help them out, but if the crisis gets worse, a reluctant Trump White House might have to come to the rescue.

By the early fall, the fear over the virus returning is another potential obstacle on the path to recovery. If the disease starts to spread again and forces more state lockdowns, all the progress made during the warmer months could be lost.

Even if the virus remains contained in the fall, the lingering threat all but ensures states will retain some restrictions, limiting the size and speed of the rebound.

“A slow reopening will limit a renewed viral outbreak, but will also prolong the stress on workers and firms,” economists at Northern Trust predicted.