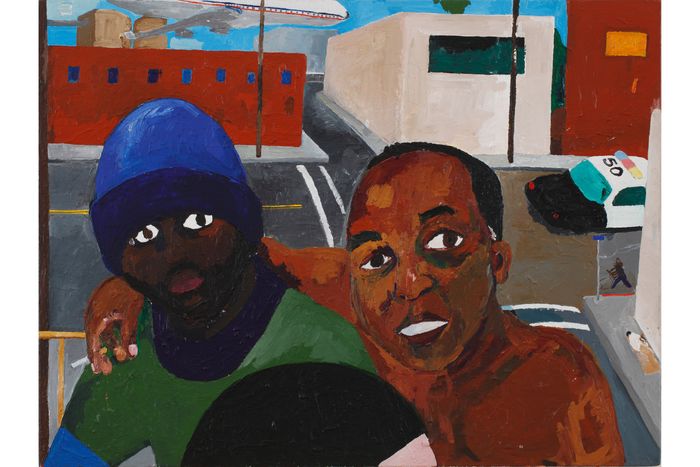

Henry Taylor once said, “I want to be all over the place.” He is! The Whitney’s new retrospective of the artist, Henry Taylor: B Side, is the best show of 2023. Every gallery has pictures that will take your breath away with their omnivorous ambition. His subjects range from his friends to strangers in his L.A. neighborhood to famous Black historical figures like Miles Davis and Cicely Tyson, who he famously depicted in front of the White House like a revisionist update on the dour couple in American Gothic. He’s done Barack and Michelle Obama, too, though you barely recognize them at home on a couch. He’s done self-portraits, murals, depictions of extreme violence committed against Black people. His inspirations include Jay-Z, Noah Davis, and the late great Bob Thompson, who appears repeatedly in a bird shape that watches over his paintings. “I want to feel free when I’m on that fucking canvas,” he has said. Taylor is about the freest artist now working.

The story of how he arrived at this position of supreme autonomy is an unlikely one. Born in Ventura, California, he was the youngest of eight children. His mother cleaned other people’s homes. His father was a painter for the U.S. government. One of his older brothers was shot at 22 and died seven years later. “I think about that a lot,” he has said. One brother became a minister, another started a Black Panther chapter in Ventura County. As a kid he’d “just watch and listen.”

Taylor graduated from CalArts in his late-thirties and didn’t have gallery representation until his mid-forties. “A lot of galleries who say they were looking at me for 20 years—that’s a motherfucking lie,” he told The Guardian in 2021. Half a lifetime of being an outsider has left its mark on his work, which describes a universe in which the line between vertiginous success and abject failure is perilously thin. “Every successful Black person has 18 members of his family living in the projects,” he has said, “and we all know someone who’s in the system.”

“There are certain things I endured that I didn’t think my son would have to endure,” he told LAXART executive director Hamza Walker in an interview for Cultured. “But we’re still having to go through these things.” B Side features many testaments to the immutability of the Black experience, most prominently an enormous untitled graphite mural that unfurls across four walls of a large gallery and retells the story of slavery and its long dreadful tail, from West Africa to the Great Migration and beyond. It culminates with a giant image of Whitney Houston with wings. There is also THE TIMES THAY AINT A CHANGING, FAST ENOUGH! from 2017, a world-upending painting that depicts the police killing of Philando Castile the year before. He is alone in the car, bleeding out, a corpse lying in what has become his tomb. A blue, twisting seatbelt divides the painting in two, one half defined by Castille’s lifeless, lidless eye, the other by a white hand holding a gun.

Yet even here, life blazes across the canvas: the sizzling colors, the big cut-out shapes, the fast but studied paint strokes, the rivulets of blood turned orange and blue. Throughout his work, bravura and heroism are mingled with the humiliation of death and defeat. In his self-portrait, based on a late-16th century painting of Henry V, Taylor is shown in profile in a plush robe and a bejeweled chain. He raises a tiny delicate hand in a blessing, a gesture of kingly greatness.

So many pictures here echo other pictures, as if Taylor were a kind of shaman of art history filling its ghostly spirits with fresh life. Before Gerhard Richter there was Cassi, from 2017, is a replica of Richter’s picture of his 11-year old daughter, Betty, but instead of a blond, white girl the subject is a Black girl with an Afro, his fellow artist Cassi Namoda. It is a point-blank shot at the era of Great White Males. His recreation of Whistler’s Mother is titled Eldridge Cleaver, featuring the Black Panther casually smoking a cigarette as he lounges in a Modernist chair.

My favorite of Taylor’s paintings are his images of everyday life. The 4th, from 2012, is a monumental painting, 13 feet tall and more than six feet wide. It could dominate a cathedral. We see a Black woman at a grill, a superb abstract composition of chicken, hot dogs, and other meats. In the background is a walled-in courtyard: a penitentiary. Perhaps she is offering a sacrifice to those incarcerated within. Perhaps this is this what the Fourth of July means to Taylor: independence served with a dose of the carceral state, yet another B Side of American history—the Black Side. He has presented this perspective with love and wit and wisdom, showing that freedom isn’t gained by transcendence but by understanding that the only way out is through.