.cms-textAlign-lefttext-align:left;.cms-textAlign-centertext-align:center;.cms-textAlign-righttext-align:right;.cms-magazineStyles-smallCapsfont-variant:small-caps;

In case you hadn’t heard, “the American dream is dead.” This is, I think, due to an “epidemic of crime.” Or maybe “bad hombres” who insisted they be subjected to “no more bullshit.”

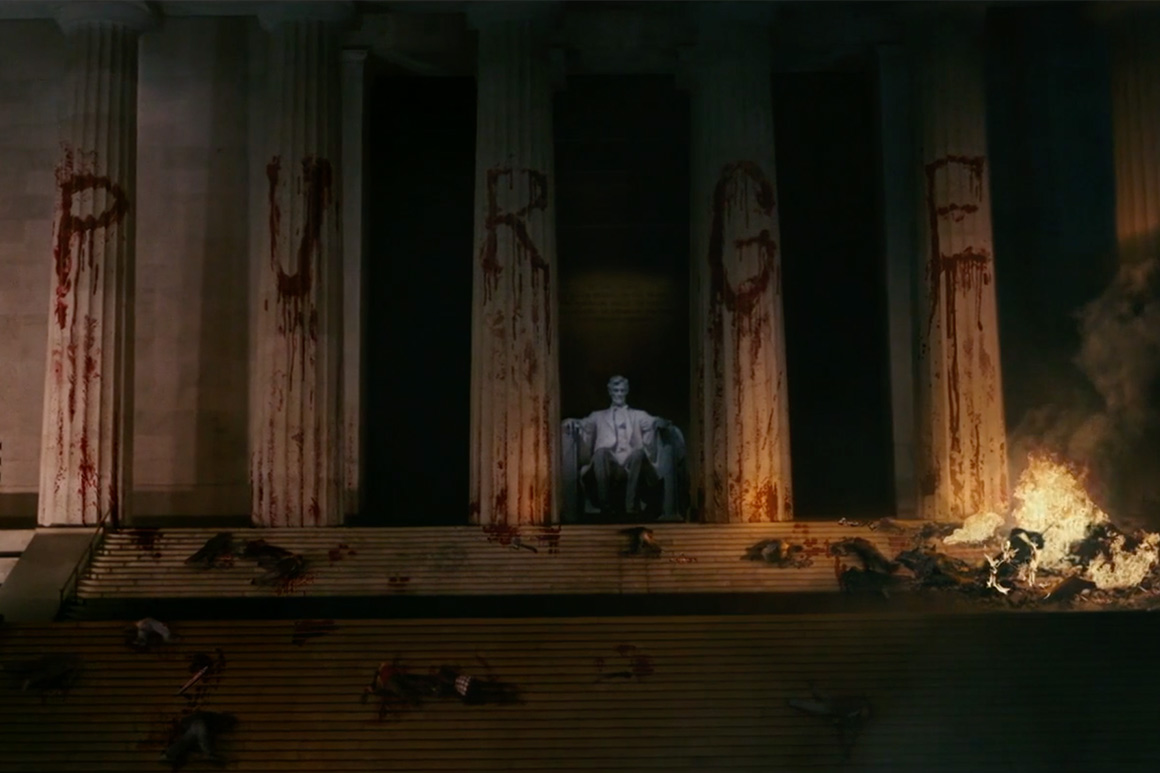

Who said these things? Donald Trump, of course (or at least, in some cases, his bootleg merchandisers). But also a menagerie of forgettable stock characters from the “Purge” horror-thriller cinematic universe. If the exact details are fuzzy, forgive me. In a span of 24 hours over the July Fourth weekend, I watched all five “Purge” films — including “The Forever Purge,” which just opened in theaters — in an attempt to understand why this aggressively off-putting, grotesque franchise has maintained its stranglehold on the American imagination for nearly a decade now.

To do what these films do not, and indulge in a little bit of understatement, it was a disorienting experience.

The “Purge” universe is based on a simple and nihilistic premise: In a dystopian near-future, a democratically-elected American theocracy legalizes any and all crime — including murder — for 12 hours each year, with the starting bell a 7:00 p.m. siren blast on March 21 that announces anarchy until the following morning. The stated purpose is to psychologically “purify” a society wracked by unemployment and rampant crime, allowing Americans to live peacefully among each other for the remainder of the year.

In (this fictional) reality, however, it’s all just a ruse by bloodthirsty oligarchs to sell guns and insurance while culling the ranks of those who can’t afford to hunker down for the night in gilded panic rooms. One part hardcore social Darwinism, one part “Escape From New York” and a sprinkle of “The Handmaid’s Tale” have combined to the tune of nearly $500 million at the worldwide box office.

That’s just a taste of the hazily sketched political philosophy the “Purge” films lay out. Regardless of their thematic ambiguity, there’s an obvious hook: They serve as opportunities for the viewer to “purge” in their own mind over the course of 90-110 minutes, imagining how they might survive in a world of unbidden violence—or what they might be tempted to do if given the chance to act with impunity. The viewer can damn the Purge’s avaricious creators while enjoying the catharsis-by-proxy of the violence they unleash. Even better, the masters of this particular universe are drawn vaguely enough that viewers of all political stripes can imagine them as the foes of their choosing: religious autocrats, a shadowy global cabal of far-right fever dreams, or anything in between.

The political details of the world conjured by franchise creator and screenwriter James DeMonaco—scattershot and contradictory as they are—reveal the driving impulses of the populist id that drives today’s politics. Now nearly a decade after its launch, one could do worse than squinting at the “Purge” franchise to glean an impressionistic, if woefully incomplete, picture of American social erosion.

***

In “The Purge,” the franchise’s 2013 maiden voyage, simplicity is a virtue. Produced on a relatively shoestring budget of $3 million, the film is effectively an old-school haunted house picture focusing on one family’s efforts to make it through Purge Night at home. The civic trappings of the franchise are almost irrelevant here, replaced by a series of straightforward moral quandaries: What do we owe our neighbors? How much risk would you take on to protect them? How far are you willing to go to protect your own family?

Those are the questions the film’s protagonist, a McMansion-dwelling but economically insecure salesman played by Ethan Hawke, faces as he glowers his way through what recalls a lengthy, uber-violent, not-very-sophisticated episode of “The Twilight Zone.” The demons at Hawke’s heavily-fortified door—he happens to peddle security systems meant to keep those who can afford them safe from the Purge—are a roving gang of “American Psycho”-style preppies, who appeal to class solidarity by imploring Hawke to release a homeless man taken in by his compassionate offspring. With its sadistic elite antagonists, the film establishes the series’ crude populism, and although it doesn’t amount to much of a social critique, the final product is probably the most satisfying in the series by virtue of its small-scale, human focus.

In its 2014 sequel, “The Purge: Anarchy,” the camera zooms way out. We’re introduced to the wider sociopolitical context of the Purge, which has created a country where unemployment is below 5 percent and “crime is virtually non-existent, while every year fewer and fewer people live below the poverty line,” as the film’s opening title card helpfully explains. Eventually, via painstaking verbal exposition, the viewer learns that the ruling party (the perfectly vaguely named “New Founding Fathers of America”) is now simply deploying death squads to indiscriminately murder the poor, who apparently have not done an efficient enough job of it themselves come Purge time.

The sequel does some things effectively. By turning its focus to the people who can’t afford to enter Ethan Hawke’s bunker, it confronts the viewer more directly with the pitch-black implications of the series’ premise, up to and including a disturbing scene of threatened sexual violence. But in what becomes a recurring theme for the franchise, that strength is also the film’s weakness. Bogged down by dull action, bizarre pacing and the ham-fisted introduction of a Black resistance group for whom the term “caricature” would be generous, “The Purge: Anarchy” introduces a raft of provocative, upsetting ideas and proceeds to do less than the bare minimum with them.

That trend largely continues in the series’ third installment, “The Purge: Election Year.” As one might surmise from the title, the film tackles electoral politics head-on. Its plot follows an idealistic, crusading politician who seeks the presidency on a single-issue platform of abolishing the Purge. Although it’s cinematically more successful than its predecessor—benefiting from tighter action sequences as DeMonaco is clearly more comfortable with the larger budget—it still lacks real thematic punch or focus. Its protagonist, portrayed by “Lost” star Elizabeth Mitchell, invokes Lincoln in a debate speech against her opponent; one of the film’s scrappy rebels faux-cynically proclaims “She’s full of it too, nothing will actually change.”

By the time the film was released in mid-2016, critics were salivating for parallels between its bleak universe and the Manichean, id political landscape that year’s real-world election had shaped. They were hard to come by. Ironically, perhaps more than any other film in the franchise, “Election Year” dodges the explicitly topical in favor of the closest thing to a throughline that exists between the five films: its vague, stick-it-to-‘em populism. When its captured antagonist implores the film’s heroes to murder him in cold blood, he repeats a common refrain from “Anarchy,” smugly reassuring them that it’s “their right as an American.” Who across the political spectrum wouldn’t like to stick it to their entitled opponents? (Here, it’s ultimately a moral victory, although action cult hero Frank Grillo does get in a solid below-the-belt shot and Arnold-style one-liner.)

The next entry, the 2018 prequel “The First Purge,” benefits from a shakeup. In its origin story of both the Purge itself and the dystopia that birthed it, we see glimpses of the political dynamics DeMonaco surmises could drive Americans to such depravity—a housing crisis, an epidemic of opioid use, widespread and uncontrollable protests. It’s the cinematic equivalent of a “You Are Here” sticker (and in case the setting wasn’t immediate enough for you, there’s a brief cameo from CNN’s Van Jones interviewing the Purge’s in-universe creator).

Despite its head-on embrace of the imagined political conditions under which such an event could take place, “The First Purge” is the most entertaining film in the series by virtue of a street-level narrative focus that recalls the series’ origins. It also benefits from easily the most charismatic “Purge” lead in Y’lan Noel (of HBO’s “Insecure”), a laconic Staten Island drug kingpin who intends to lay low as the new government uses his borough as the Purge’s experimental testing ground.

Of course, he does not succeed, and the film follows him and a largely Black cast of Staten Islanders as they attempt to escape the Purge night’s violence. Of all the “Purge” films, “The First Purge” most directly acknowledges the ugly reality that many Americans would no doubt use such an opportunity to vent their racial animus in horrific and violent ways. An indelible, disturbing image of Noel choking the life from a white stormtrooper in a Sambo mask hits far harder than similar agitprop from across the series. The filmmakers clearly grasp, for the first time, that without nailing the “humanity” part of “inhumanity,” depicting it is ultimately just an exercise in morbid juvenilia.

Which brings us to “The Forever Purge.” Like its predecessors, the newest “Purge” flick gleefully prods at raw wounds in the American psyche, depicting societal tensions as the basis for grisly violence. And it does so while providing an allegory more explicit than any film in the series thus far. In a town on the northern side of the U.S.-Mexico border, racist paramilitary groups keep the annual violence going past its legally-sanctioned window in an attempt to rid American society of non-whites. A Hallmark-handsome family of white ranchers with a pregnant matriarch and their Mexican migrant colleagues then must make a treacherous border crossing to Mexico to escape the violence, in a predictable inversion of the typical North American refugee narrative.

While its politics are stated more clearly than any other film in the series, the allegory isn’t nearly clever enough to overcome the same two-dimensional characters and formulaic action that have historically depressed the franchise’s Rotten Tomatoes score. The audience is now apparently catching up to the critics, with the film opening to the series’ lowest box office even as movie theaters wake from their pandemic slumber. The film is, simply, not very good, an inert border-crossing thriller onto which the franchise’s stale trappings are welded.

It ends, however, on an odd but revealing note: an audio collage of news broadcasts reporting that across the country, people are banding together to fight back against the racist militias that have overwhelmed the … racist theocracy. (I know.) It seems like an uncharacteristically hopeful note to end on for such a bleak series, but to close “Purge” watchers, it should make perfect sense: Against all odds, the films have a fundamentally optimistic view of human nature. Time and again, it’s established that most people are, in fact, not interested in murder, rape, arson and the like, and that the depraved violence depicted is perpetrated by mostly either psychotic outliers or a government dissatisfied with its charges’ lack of bloodlust.

That confidence in human nature reveals the fundamental flaw at the heart of the “Purge” series, and why its politics seem so head-spinningly inconsistent. The films are abrasive, button-pushing, and purposely confrontational in a way that plays on the viewers’ own insecurities and fears about the state of America’s social contract. Their subliminal reassurance of the viewer, however, defangs them in the absence of any meaningful critique. The series fails to either confront the viewer directly enough to reach any kind of real insight about the world, or provide the quality of dumb-fun pulp entertainment that would make us not care.

To take “The Purge” franchise as emblematic of our times, then, might be done better by examining its style rather than its content: Angsty, fearful, lacking clarity but willing to point an omni-directional and accusatory finger at a moment’s notice. Judging by last weekend’s aforementioned box office, the past few years of American life have somewhat exhausted our appetite for such fare. The series’ creators, however, surely appreciate that fate on some level. To quote one of the universe’s various hulking brutes, who shouts the phrase unbidden like a mantra, it’s “survival of the fucking fittest.”