Economy

The Irrelevant Recession: Congress Needs To Reverse Course To Improve The Economy – Forbes

Recession talk has dominated the news lately with an endless supply of pundits debating whether the United Sates is in a recession. It’s good to have that debate, but virtually everyone seems to have forgotten the incredibly abnormal circumstances fueling the dispute.

That’s not to say that anyone should ignore the bad policies–there are tons of them–contributing to economic turmoil, but policymakers will just make things worse if they lose sight of what’s happened. The obvious starting point is early 2020.

When COVID-19 started spreading across the country, state and local governments issued stay-at-home orders and effectively shut down the economy. The resulting drop in consumer purchases was unlike anything the nation has previously experienced.

Between the fourth quarter of 2019 and the second quarter of 2020, nominal gross domestic product (NGDP) fell from $21.7 trillion to $19.5 trillion. This 10.22% decline surpasses anything in the historical record. (And although everyone seems to forget, it was followed by a decline in the overall price level.)

Then, almost without warning, the economy roared back to life.

Between the second quarter of 2020 and the fourth quarter of 2020, NGDP increased by 10.27%. Although the NGDP growth rate came very close to this figure in 1950, the 2020 increase is the largest two-quarter increase in the historical record. And it was followed by another 8% increase through the third quarter of 2021.

Naturally, the massive drop in demand caused all kinds of supply problems, and with so many people unable to work, it spurred a burst of federal spending. By the time all was said and done, Congress had pumped out almost $7.5 trillion in stimulus, boosting Americans’ disposable income well above the average growth rate.

Unsurprisingly, the massive surge in consumer demand worsened the many supply-side problems caused by the pandemic and the government-imposed shutdowns, and inflation took off at rates not seen in 40 years.

So, regardless of how one labels the current economy, it is not part of anything close to a normal business cycle.

And forecasters should drop any pretense that they know when things will get back to normal because all such forecasts depend on wildly abnormal data. In other words, forecasting economic outcomes–something that was already, to say the very least, hit or miss–is virtually impossible right now because the data is so anomalous.

These issues are bad enough for anyone who insists on identifying whether the United States is in a recession, but an even bigger problem is that there is no objective definition of a recession. None whatsoever.

As a result, all arguments about whether the economy is formally in a recession are equivalent to unsubstantiated opinion.

It is even somewhat dicey to compare official recessions through time because the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) does not use an objective, consistent definition. The official statement reads as follows:

The NBER’s definition emphasizes that a recession involves a significant decline in economic activity that is spread across the economy and lasts more than a few months. In our interpretation of this definition, we treat the three criteria—depth, diffusion, and duration—as somewhat interchangeable. That is, while each criterion needs to be met individually to some degree, extreme conditions revealed by one criterion may partially offset weaker indications from another.

…

Because a recession must influence the economy broadly and not be confined to one sector, the committee emphasizes economy-wide measures of economic activity. The determination of the months of peaks and troughs is based on a range of monthly measures of aggregate real economic activity published by the federal statistical agencies. These include real personal income less transfers, nonfarm payroll employment, employment as measured by the household survey, real personal consumption expenditures, wholesale-retail sales adjusted for price changes, and industrial production. There is no fixed rule about what measures contribute information to the process or how they are weighted in our decisions. [Emphasis added.]

A significant decline? More than a few months? Three interchangeable criteria? (And they can offset one another?) No fixed rule? And a bunch of economists have to agree before calling the recession dates?

It’s amazing there is just one set of NBER business cycle dates.

Rather than argue over whether the American economy is in a recession, it makes just as much sense to point out that GDP has declined in consecutive quarters only 5 times since 1947, so the current situation is surely bad.

While that’s not much of a revelation to anyone who’s been paying attention, even right now, in the most abnormal of times, there are both good and bad signs.

For instance, GDP has declined in consecutive quarters, inflation is high, and both total nonfarm payrolls and labor force participation remain below their pre-pandemic levels. Housing starts have fallen to a nine-month low.

On the other hand, the second quarter GDP decrease was smaller than the first quarter decrease, consumer spending has remained strong, industrial production is growing, and personal income increased in both the first and second quarters. Moreover, household balance sheets are strong. For example, debt service payments as a percent of disposable personal income are at an all-time low (the series starts in 1980).

None of these positive signs are meant to “prove” things are fine, or to excuse the policy mistakes that have made the economy worse. There are, in fact, tons of bad policies that have legitimately caused millions of people to bicker over exactly how bad things have gotten.

On the major issues, though, it could be the case that there is no simple policy solution.

For instance, the United States labor market might be in the middle of major shifts due to years of bad policies, the consequences of which the pandemic and government shutdowns simply sped up. The employment gap remains almost 2 percent, meaning that employment is almost 2 percent below where the pre-pandemic trend suggests it would otherwise be right now. However, a close look suggests that the bulk of this gap is explained by workers 65 and older deciding to retire and, to a lesser but large extent, 20 to 24 year-olds dropping out of the labor force.

For years, businesses have been complaining about how hard it is to find workers and warning of the impending retirement of baby boomers. And demographers have long noted the trend toward having less children, but critics consistently scoffed at the idea that there was an actual labor shortage in the United States.

Against that backdrop, Congress steadfastly refused to make any major reforms to the badly broken immigration system, pretty much the only way to get more workers. Whatever the reason, business owners now find themselves having to pay workers more, a higher cost that tends to put upward pressure on consumer prices, thus worsening inflation. (Disturbingly, productivity is at a 75-year low, but that’s for another column.)

And given the supply-side problems that are contributing to high inflation, the Fed finds itself in a major pickle. It must fight inflation to fulfill its legislative mandate and maintain credibility, but it knows that monetary policy is ineffective against price level increases caused by supply-shocks.

So that leaves Americans at the mercy of Congress for positive policy responses, and that’s a most unfortunate position.

In practical terms, the only thing Congress does well is spend other people’s money, exactly the wrong prescription to fight inflation. The recent $7.5 trillion in stimulus/pandemic relief has worsened supply-side problems, driving prices higher. More government spending will only do the same, so for the love all that exists in the universe, Congress should slow its spending roll. (Congress should also ignore the critics who want higher taxes to stem inflation, but I’m pretty sure members don’t need much convincing that now is a bad time to raise taxes.)

Americans would be far better off if the federal government stepped back right now, but Congress doing less is even rarer than consecutive quarterly declines in GDP.

If Americans are lucky, gridlock will set in and there will be no major spending increases prior to the next election. If they’re extremely lucky, Congress will enact major policy reforms that free up private sector workers–even those that produce fossil fuel energy products–to increase the supply of goods and services. It would help clear supply constraints and lower prices, providing more economic opportunities for millions of Americans.

Those would be incredibly abnormal circumstances on Capitol Hill, but that’s how Congress can help fix the bad economy.

Economy

China Wants Everyone to Trade In Their Old Cars, Fridges to Help Save Its Economy

|

|

China’s world-beating electric vehicle industry, at the heart of growing trade tensions with the US and Europe, is set to receive a big boost from the government’s latest effort to accelerate growth.

That’s one takeaway from what Beijing has revealed about its plan for incentives that will encourage Chinese businesses and households to adopt cleaner technologies. It’s widely expected to be one of this year’s main stimulus programs, though question-marks remain — including how much the government will spend.

Economy

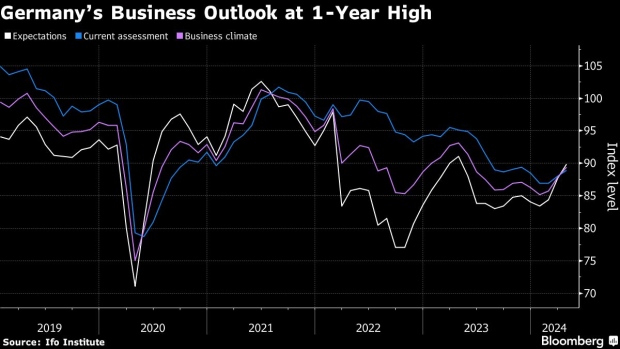

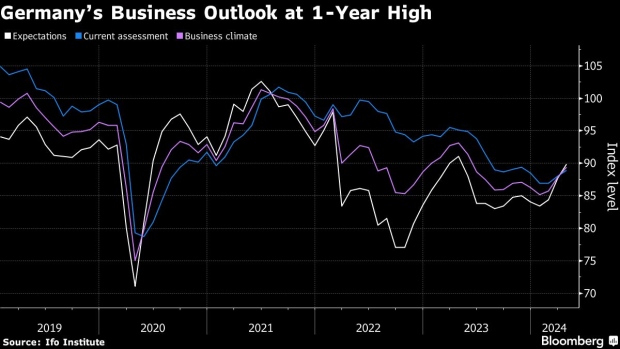

German Business Outlook Hits One-Year High as Economy Heals

|

|

German business sentiment improved to its highest level in a year — reinforcing recent signs that Europe’s largest economy is exiting two years of struggles.

An expectations gauge by the Ifo institute rose to 89.9. in April from a revised 87.7 the previous month. That exceeds the 88.9 median forecast in a Bloomberg survey. A measure of current conditions also advanced.

“Sentiment has improved at companies in Germany,” Ifo President Clemens Fuest said. “Companies were more satisfied with their current business. Their expectations also brightened. The economy is stabilizing, especially thanks to service providers.”

A stronger global economy and the prospect of looser monetary policy in the euro zone are helping drag Germany out of the malaise that set in following Russia’s attack on Ukraine. European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde said last week that the country may have “turned the corner,” while Chancellor Olaf Scholz has also expressed optimism, citing record employment and retreating inflation.

There’s been a particular shift in the data in recent weeks, with the Bundesbank now estimating that output rose in the first quarter, having only a month ago foreseen a contraction that would have ushered in a first recession since the pandemic.

Even so, the start of the year “didn’t go great,” according to Fuest.

“What we’re seeing at the moment confirms the forecasts, which are saying that growth will be weak in Germany, but at least it won’t be negative,” he told Bloomberg Television. “So this is the stabilization we expected. It’s not a complete recovery. But at least it’s a start.”

Monthly purchasing managers’ surveys for April brought more cheer this week as Germany returned to expansion for the first time since June 2023. Weak spots remain, however — notably in industry, which is still mired in a slump that’s being offset by a surge in services activity.

“We see an improving worldwide economy,” Fuest said. “But this doesn’t seem to reach German manufacturing, which is puzzling in a way.”

Germany, which was the only Group of Seven economy to shrink last year and has been weighing on the wider region, helped private-sector output in the 20-nation euro area strengthen this month, S&P Global said.

–With assistance from Joel Rinneby, Kristian Siedenburg and Francine Lacqua.

(Updates with more comments from Fuest starting in sixth paragraph.)

Economy

Parallel economy: How Russia is defying the West’s boycott

|

|

When Moscow resident Zoya, 62, was planning a trip to Italy to visit her daughter last August, she saw the perfect opportunity to buy the Apple Watch she had long dreamed of owning.

Officially, Apple does not sell its products in Russia.

The California-based tech giant was one of the first companies to announce it would exit the country in response to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

But the week before her trip, Zoya made a surprise discovery while browsing Yandex.Market, one of several Russian answers to Amazon, where she regularly shops.

Not only was the Apple Watch available for sale on the website, it was cheaper than in Italy.

Zoya bought the watch without a moment’s delay.

The serial code on the watch that was delivered to her home confirmed that it was manufactured by Apple in 2022 and intended for sale in the United States.

“In the store, they explained to me that these are genuine Apple products entering Russia through parallel imports,” Zoya, who asked to be only referred to by her first name, told Al Jazeera.

“I thought it was much easier to buy online than searching for a store in an unfamiliar country.”

Nearly 1,400 companies, including many of the most internationally recognisable brands, have since February 2022 announced that they would cease or dial back their operations in Russia in protest of Moscow’s military aggression against Ukraine.

But two years after the invasion, many of these companies’ products are still widely sold in Russia, in many cases in violation of Western-led sanctions, a months-long investigation by Al Jazeera has found.

Aided by the Russian government’s legalisation of parallel imports, Russian businesses have established a network of alternative supply chains to import restricted goods through third countries.

The companies that make the products have been either unwilling or unable to clamp down on these unofficial distribution networks.

-

Health21 hours ago

Health21 hours agoRemnants of bird flu virus found in pasteurized milk, FDA says

-

News18 hours ago

Amid concerns over ‘collateral damage’ Trudeau, Freeland defend capital gains tax change

-

Art22 hours ago

Random: We’re In Awe of Metaphor: ReFantazio’s Box Art

-

Art15 hours ago

The unmissable events taking place during London’s Digital Art Week

-

Politics19 hours ago

Politics19 hours agoHow Michael Cohen and Trump went from friends to foes

-

Science20 hours ago

NASA hears from Voyager 1, the most distant spacecraft from Earth, after months of quiet

-

Tech22 hours ago

Surprise Apple Event Hints at First New iPads in Years

-

Media21 hours ago

Vaughn Palmer: B.C. premier gives social media giants another chance