Updated on November 7, 2020 at 11:55 a.m. ET

Two themes seem to define the 2020 election results we’ve seen so far—and also build on a decade or more of political developments: the depolarization of race and the polarization of place.

Democrats have historically won about 90 percent of the Black vote and more than 65 percent of the Latino vote. But initial returns suggest that Joe Biden might have lost ground with nonwhite voters.

The most obvious drift is happening among Latinos. In Florida, Biden underperformed in heavily Latino areas, especially Miami-Dade County, whose Cuban American population seems to have turned out for Donald Trump. Across the Southeast, majority-Latino precincts in Florida, Georgia, and North Carolina swung 11.5 points toward Republicans since 2016. In southern Texas, Trump won several heavily Latino counties in the Rio Grande Valley, including Zapata, the second-most-Latino county in the country, which hadn’t voted for a Republican in 100 years. Even in the Democratic fortress of Massachusetts, cities with the highest share of Latino voters saw the starkest shifts toward Trump, according to Rich Parr, the research director for the MassINC Polling Group.

Some evidence suggests that Biden lost support among other minority groups as well. In North Carolina’s Robeson County, where Native Americans account for a majority of voters and which Barack Obama won by 20 points in 2012, Biden lost by 40 points. In Detroit, where nearly 80 percent of the population is Black, Trump’s support grew from its 2016 levels—albeit by only 5,000 votes. (Exit polls also found that Black and Latino men in particular inched toward Trump in 2020, but these surveys are unreliable.)

The slight but significant depolarization of race didn’t happen out of nowhere. As the pollster David Shor told New York magazine in July, Black voters trended Republican in 2016, while Latino voters also moved right in some battleground states. “In 2018, I think it’s absolutely clear that, relative to the rest of the country, nonwhite voters trended Republican,” he said. “We’re seeing this in 2020 polling, too. I think there’s a lot of denial about this fact.” After this election, the trend may be harder to deny.

A caveat: The 2020 election data are still incomplete. Nonwhite voters still lean Democratic, and one shouldn’t overstate the degree to which their shift at the margins is responsible for Trump’s overall level of support. Finally, race is a messy and often-forced category. While it is sometimes useful to talk about a Latino electorate as distinct from, say, the Black vote, there is really no such thing as a singular Latino electorate, but rather a grab bag of Latino electorates, varying by geography, gender, generation, country of origin, and socioeconomic status.

The depolarization of race will make it harder for Democrats to count on demography as a glide path to a permanent majority. It should make them think hard about how a president they excoriate as a white supremacist somehow grew his support among nonwhite Americans. But in the long run, racial depolarization might be good for America. A lily-white Republican Party that relies on minority demonization as an engine for voter turnout is dangerous for a pluralist country. But a GOP that sees its path to victory winding through a diverse working class might be more likely to embrace worker-friendly policies that raise living standards for all Americans.

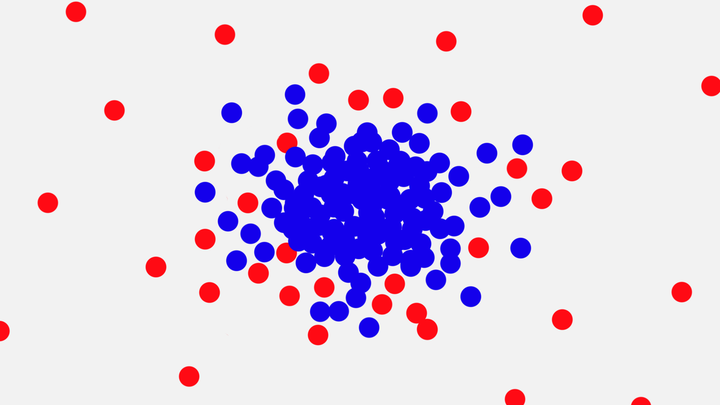

Even more than the depolarization of race, the polarization of place is a long-running trend. In the past 100 years, Democrats have gone from being the party of the farmland to a profoundly urban coalition. In 1916, Woodrow Wilson’s support in rural America was higher than his support in urban counties. Exactly one century later, Hillary Clinton won nine in 10 of the nation’s largest counties and took New York City, Boston, Denver, Atlanta, Philadelphia, and Chicago by more than 50 points. Now it looks like Biden won the election by running up the score in cities and pushing the inner suburbs left, even as Trump strengthened his grip on rural areas.

Wisconsin offers a good illustration of place-based partisan evolution. The state has been decided by less than one percentage point four times in the past six elections, but the distribution of votes has changed immensely in that period. In 2000, Al Gore won the largest county, Milwaukee, by about 20 percentage points and eked out a 5,000-vote victory in rural areas such as Pepin County, the birthplace of the Little House on the Prairie author, Laura Ingalls Wilder. In white, wealthy suburban areas such as Waukesha, he got clobbered by more than 30 points. This year, Biden doubled Gore’s margin in Milwaukee to 40 points and significantly narrowed the gap in Waukesha, while Trump cleaned up in Pepin. Thus, two Democrats separated by two decades won Wisconsin by less than 0.5 percent—Gore with a metro-rural coalition and Biden with a big metro surge that carried over into the white-collar suburbs.

This story is playing out across the country. The economist Jed Kolko calculated that, as of midday yesterday, large urban areas remained staunchly pro-Democrat as inner suburbs moved hard to the left. In the Northern Virginia suburb of Fairfax, just across the river from Washington, D.C., Biden won 70 percent of the votes in a county that George W. Bush carried in 2000. Meanwhile, Kolko found, Trump held on to a 40-point lead in rural America and gained votes in low-density suburbs, such as Ocean, New Jersey, outside New York City. From coast to coast, inner suburbs are voting more like cities—that is, for Democrats—and outer suburbs are voting more like rural areas, for Republicans.

Driving both the polarization of place and the depolarization of race is the diploma divide. Non-college-educated Latino and Black Americans are voting a little bit more like non-college-educated white Americans, and these groups are disproportionately concentrated in sparser suburbs and small towns that reliably vote Republican. Meanwhile, low-income, college-educated 20-somethings, many of whom live in urban areas, are voting more like rich, college-educated people who tend to live in the inner suburbs that are moving left.

Demographics were never destiny. Density and diplomas form the most important divide in American politics. At least for now.

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.