Politics

The new politics of climate change – Financial Times

A billionaire, a novelist and a professor all write a book about climate change.

That may sound like the start of a joke but it is not, especially for philanthropist Bill Gates and author Jonathan Franzen. Their books have come out just as Michael E Mann, one of the world’s best known climate scientists, has published a book accusing each of abetting new forces of inactivism slowing efforts to tackle climate change.

It is hard to think of another time the publishing world has delivered such an engaging spectacle. As raging wildfires and deadly floods drive a new sense of urgency, the debate about how to curb global warming has spread far beyond the scientists, economists and activists who once dominated the field. We are all, as it were, environmentalists now.

Yet the scale of the climate problem makes it hard to know what constitutes a meaningful response. Is it enough to give up meat and flying? Do we need a slew of technological breakthroughs? Or is disaster now inevitable and any sort of action too late?

These three books address all these questions, but none so comprehensively as Mann. The Pennsylvania State University professor has had an unusually vivid view of the battle to cut the world’s dependence on fossil fuels.

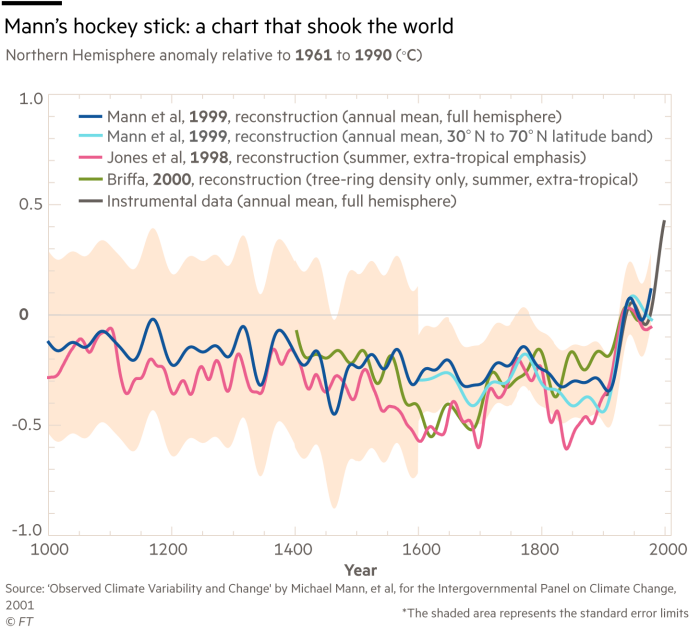

He was still in his early thirties in 1998 when he and two colleagues published what has been called the most controversial chart in science: the hockey stick. At a time of widespread denial about climate change, their simple graph showed global temperatures had varied little for centuries, but shot up after fossil fuel burning took off after the industrial revolution. In other words, the world was warming at a rate unseen in modern history and humans were causing it.

Mann faced a blistering effort to discredit his work — and even death threats. In the US, Republicans in Congress, many of them recipients of fossil fuel industry donations, accused him of inaccuracy, fraud and worse, as he recounted in his 2012 book, The Hockey Stick and the Climate Wars.

Nearly a decade later, the science behind the hockey stick remains robust. Yet Mann makes a convincing case that the fight against climate action continues — under different terms of engagement. “Outright denial of the physical evidence of climate change simply isn’t credible any more,” he writes in The New Climate War. The war on the science has ended, he says. But in its place has come a war on climate action, or “a softer form of denialism” in which “inactivists” deploy a mix of deception, deflection and distraction to delay cuts in emissions.

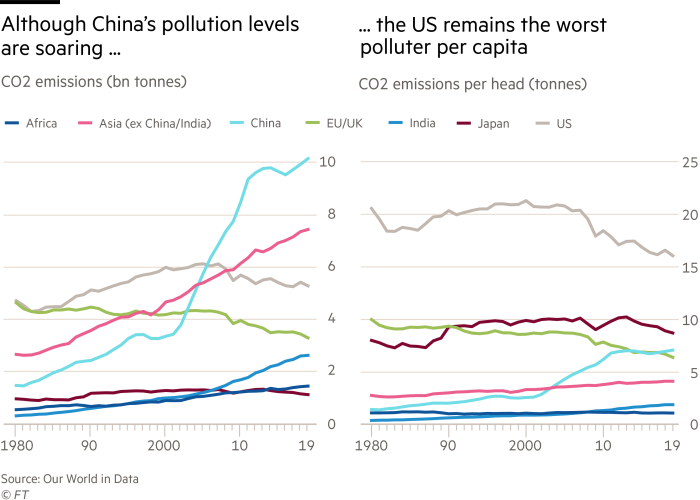

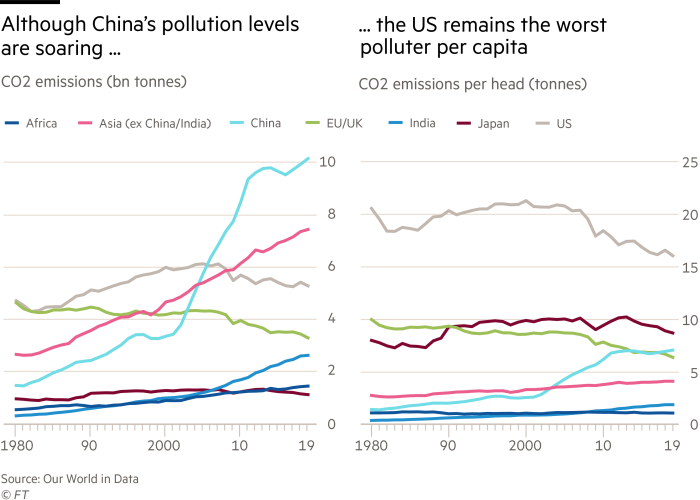

Many readers will be surprised to learn that one of Mann’s chief complaints concerns flight-shaming, vegan diets and other types of individual behaviour widely thought to be central to tackling climate change. Personal actions can help, and often set a sensible example. But, as Mann writes, they cannot rival broad, systemic measures such as carbon pricing or ending fossil fuel subsidies. For all the scrutiny of flying, it currently accounts for about 3 per cent of global carbon emissions.

Worse, some research suggests a focus on personal behaviour creates an illusion of progress that can erode support for more effective collective policies. One study found the more people switched off lights and scrimped on household energy use, the less likely they were to support a carbon tax.

Dwelling on individual behaviour is also a “particularly devious” deflection strategy, Mann argues, because it breeds divisive finger-pointing among campaigners and attempts to render leaders as elite hypocrites. Celebrity climate activist Leonardo DiCaprio, for instance, is often lambasted for flying in a private jet. After Al Gore released his 2006 documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, claims emerged that his home used 20 times more energy than the average American house.

Mann shows attention on personal action did not occur in a vacuum. Oil companies were early promoters of the personal carbon footprint calculator and there is a well-thumbed playbook for industries seeking to divert attention from their own activities to individuals using their products. The US gun lobby claims “guns don’t kill people, people kill people” to fend off tougher laws; beverage groups back campaigns against roadside litter created by their own bottles and cans.

Some of Mann’s other examples of soft denialism are even more insidious because they are promoted by green activists themselves. Exhibit one: what he calls climate “doomists” who promote the idea that all hope is lost and action is fruitless, which is where Jonathan Franzen comes in.

The best-selling US novelist is no climate denier. But in 2019 he caused an outcry with an elegantly written New Yorker magazine article titled “What if We Stopped Pretending?” which argued climate disaster was all but certain and it made sense to focus on how to use finite resources to deal with it. His new 70-page booklet bears the same title and includes the article, along with an interview Franzen gave a German journalist to expand on his views. “All-out war on climate change made sense when only as long as it was winnable,” says Franzen. Human nature has made meaningful climate action almost impossible and “a false hope of salvation can be actively harmful,” he argues. Preparing for floods, fires and refugees might be more pertinent.

The essay reads at times like an elegiac counsel of despair. For the pugnacious Mann it is far worse. He devotes nearly four pages to what he calls “one of the most breathtakingly doomist diatribes” ever written. The fundamental problem with the article, Mann rails, is that it attempts “to build a case for doom on a flimsy foundation of distorted science”.

Mann argues that it is still possible to avert 2C of warming and that every bit of carbon that is not burnt prevents additional damage. “There is both urgency and agency,” he says. Social and political changes also give him cause for cautious optimism. Apart from the fact that outright denialism is fading and that climate action advocates such as Joe Biden are being elected, he is buoyed by the youth climate movement and the rise of investors rethinking the risks of fossil fuel investments.

In addition, he thinks the Covid crisis has reawakened appreciation of science, while pandemic recovery plans have opened opportunities for green investments. “We appear to be nearing the much-anticipated tipping point on climate action,” he writes.

Yet the urgency of the problem remains, which is what leads Mann to cite Bill Gates on several charges of climate inactivism.

The Microsoft co-founder is not an obvious target. Unlike other billionaires bent on reaching Mars or the Moon, Gates has spent vast sums to improve the lives of the poorest on this planet. He warned of the need to prepare for a global pandemic years before the current crisis and is now leading vaccine efforts to defeat Covid-19. He is also a lavish backer of technologies to avert what he says is the very real threat of global warming, as he details in his book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster.

Yet Gates has long irked many climate campaigners. He has raised doubts about using green energy in developing countries (a form of inactivism for Mann) and scorned the idea of fossil fuel divestment, telling the FT in 2019 it had “zero” impact on emissions.

In his new book, Gates reveals he actually divested his direct holdings in oil and gas companies in 2019. He still supports what Mann calls “non-solution solutions” offering the illusion of climate action, such as geoengineering schemes to offset warming carbon emissions. Gates has long been among the largest funders of research into such efforts, which can range from directly capturing carbon dioxide from the air to shooting sulphate particles into the atmosphere to mimic the cooling effects of volcanic eruptions.

For Mann, these schemes come under the heading of “dangerous techno-fixes” that appeal to free-market conservatives — by suggesting government regulation is unnecessary — but entail hugely risky “tinkering” with complex Earth systems we do not fully understand.

Gates acknowledges such concerns, admitting that unproven geoengineering concepts raise “thorny ethical issues”. He adds that his funding for such efforts is “tiny” compared to his other climate financing. But he still thinks the approach is worth investigating “while we still have the luxury of study and debate”.

The idea that there is time to develop meaningful climate solutions underpins a central theme of the book, namely that existing green technologies are not enough and must be augmented by big innovation breakthroughs. “We have some of what we need, but far from all of it,” he says.

This puts Gates on one side of a debate between those who think the climate problem will be solved by technology, versus those who believe the technology needed is here and what is required is more political will and policies to deploy it.

Mann belongs to the latter camp. “Sorry Bill Gates, but we don’t need a miracle,” he writes, pointing to academics who showed years ago that existing renewable energy and storage technologies could meet up to 80 per cent of global energy demand by 2030, and 100 per cent by 2050.

The framework Gates uses to support his view is based on his idea of the “green premium”, or the extra cost of zero-carbon technologies compared with fossil fuel alternatives. The average cost of a gallon of conventional jet fuel, for instance, is $2.22, while jet biofuels cost about $5.35, so the green premium adds up to $3.13.

He argues that clean technologies should only be deployed if they have a low or zero green premium, which by his analysis excludes all but a handful of options, such as home air heat pumps in some cities which in certain cases can actually be cheaper than fossil fuel alternatives. That is, he admits, partly because fossil fuel prices do not reflect the damage they inflict, and meaningful carbon pricing will be “crucial” to eliminating green premiums.

This analysis is useful. So too is his accessible description of what needs to be done to tackle climate change: bring the 51bn tons of greenhouse gases typically emitted globally each year down to zero.

Some readers may find his folksy tone, and occasional fart joke, more agreeable than Mann’s punchier work. Others may wonder how Gates managed to write an entire book on climate action that scarcely mentions the powerful political forces bent on thwarting it.

Either way, his approach leads him down some curious paths, especially when it comes to the state of existing renewables. Readers in the UK, who have been getting more than 10 per cent of their electricity from offshore wind farms this year, will be surprised to see Gates describe offshore wind as a green idea “currently in the proof phase” of market development, along with low-carbon cement.

Likewise, Gates is oddly dismissive of the idea that emissions should fall fast this decade, despite UN science reports showing global emissions should halve by 2030, and reach net zero by 2050, to avoid 1.5C of warming. “Making reductions by 2030 the wrong way might actually prevent us from ever getting to zero,” he claims. We might, for instance, replace coal power plants with gas-fired ones that have carbon capture equipment but still emit greenhouse gases. Theoretically, that is a risk. But so is waiting years for innovation breakthroughs that do not arrive.

Ultimately, Gates and Mann probably agree more than they disagree. Each wants action to curb warming emissions that pose a dire threat to the climate and, considering the torrid state of climate disputes in very recent history, that is a welcome relief.

The New Climate War: The Fight to Take Back Our Planet, by Michael E Mann, Scribe, RRP£16.99, 368 pages

How To Avoid A Climate Disaster: The Solutions We Have and the Breakthroughs We Need, by Bill Gates, Allen Lane, RRP£20/Knopf RRP$26.95, 272 pages

What If We Stopped Pretending? by Jonathan Franzen, Fourth Estate, RRP£7.99, 70 pages

Pilita Clark is an FT business columnist

Join our online book group on Facebook at FT Books Café

Politics

Are settler politics running unchecked in Israel? – Al Jazeera English

In Israel, the far right is increasingly influential in politics, with a government reliant for its existence on a settler movement driving an ever-more extreme agenda.

Analysts point out that settler and ultra-right-wing voices have come to dominate the cabinet, providing legal and political cover for even more expansion into internationally recognised Palestinian territory, and underpinning much of the ferocity of Israel’s war on Gaza.

And yet, despite that, and irrespective of the international criticism of Israel that continues to grow, the United States continues to fund it.

US lawmakers in the Senate voted on Tuesday, by an overwhelming majority, to transfer $17bn in military aid to Israel.

Celebrating the passage of the bill, House House Majority leader Chuck Schumer told the Senate: “Tonight we tell our allies: ‘We stand with you.’

“We tell our adversaries: ‘Don’t mess with us.’ We tell the world: ‘The United States will do everything to safeguard democracy and our way of life.’”

Settlers and politics

But in Israel, “democracy” and the system that Schumer and other US politicians back involves the illegal settlement of occupied Palestinian land, displacing the native population, and creating a dual system of governance, with Jews ruled under Israeli civil law, and occupied Palestinians under military law.

These settlements now dot much of the occupied West Bank, either gathering in established clusters, or in outposts that even the Israeli state deems illegal, but does little about.

As their numbers and political support have grown, settlers have become more confident, attacking Palestinian villages in well-armed and coordinated raids, occasionally with military support, and evicting Palestinian villagers.

In tandem with the expansion of the settlements has been a wider rightward drift across Israeli society, which saw the country elect its most right-wing parliament or Knesset in its history in November 2022.

Among its members are extreme-right provocateur Itamar Ben-Gvir – convicted of incitement in 2007 – who acts as national security minister, and Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich, whose claims to Palestinian territory in the occupied West Bank run counter to international law.

“The settler and far-right movements have been growing rapidly within Israel for years, to the point where forming a government is impossible without participation from right-wing parties opposed to territorial compromise with Palestinians,” Omar H Rahman of the Middle East Council on Global Affairs said.

Ben-Gvir and Smotrich, members of the right-wing coalition cabinet of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, speak to a growing constituency characterised as “messianic” in its approach to Palestinians and their land, according to analysts.

Settlers’ ideologies – which claim, among other things, a religious justification for their taking of Palestinian land – have been a growing political presence since the 1967 war, which resulted in Israel occupying the Gaza Strip, the Sinai Peninsula, the West Bank, and East Jerusalem.

“The US has played a significant role in this rightward shift by ensuring Israel’s impunity for relentless illegal settlement building, thereby undercutting those within Israeli politics who warned of the consequences of unfettered expansionism,” Rahman said. “This demonstrated to the Israeli public there would be no penalty for supporting those in Israel who want all the land ‘between the river and the sea’.”

Israel has seemingly run a violent campaign in the occupied West Bank in parallel to its war on Gaza, which followed a Hamas-led attack into Israel in which 1,139 people were killed and some 200 taken into Gaza.

As of March of this year, 7,350 Palestinians had been arrested by Israeli forces across the West Bank, many without charge and with no hope of due process.

In the last few days, rights group Amnesty International has sharply criticised settler attacks on Palestinians and what it calls the established system of apartheid that reigns in the occupied West Bank.

In the days following the discovery of the body of 14-year-old Binyamin Ahimeir, himself from an illegal Israeli West Bank settlement, hundreds of settlers went on a deadly rampage between April 12 and 16, torching homes, fruit trees and vehicles.

By the end of their attack, four Palestinians lay dead, killed by either settlers or Israeli military forces, Amnesty said, including Omar Hamed, a 17-year-old boy from near Ramallah.

An estimated 487 Palestinians have been killed in the occupied West Bank in attacks by armed settlers, often supported by security forces according to witnesses, or by security forces in near-nightly raids on towns and refugee camps and in other incidents.

Israel’s war on Gaza has killed at least 34,262 people. The true figure is likely far higher.

Netanyahu and the settlers

While Netanyahu has officially rejected settler ambitions for Gaza, he does have two settler ministers in his cabinet and the movement is continuing to grow.

Expectations that prime minister Netanyahu might act as a check on settler ambitions have also proven ill founded. Since at least 2015, both he and his Likud party have been joining with the extreme elements of the right by running campaigns noted for their dog whistle racism, Eyal Lurie-Paredes of the Middle East Institute said.

“It’s not just about the present,” Lurie-Paredes added, “It’s about the future.

“Most political party, not just Likud, has ever really opposed the settlements. They’re a winning card. The main two sectors of the population of settlers – national orthodox and ultra-orthodox – have the highest birth-rate among Israeli Jews high birth-rates. Out of Jewish first graders, more than 40 percent belong to these groups.

Additionally, Israeli governments have created a more enhanced welfare state in the West Bank for Jews, offering them better infrastructure and cheaper housing – which or drive people to move there and increase their belonging to the settler movement” he added.

Referring to the years leading up to Israel’s founding in 1948, Tel Aviv-based analyst Dahlia Scheindlin said “Settler politics have always been there.”

“However,” she noted, “it had never really been especially religious. That element only really entered the political mainstream after the 1967 war. From that point, the idea developed that territorial expansion was part of messianic redemption took hold as a specific theology among certain religious Jews.

“In tandem to this was a state that was ready to facilitate settlements covertly. However, more recently, Likud’s own populist mandate has become indistinguishable from that of Smotrich and Ben-Gvir, and now we have a government openly embracing settlers, the extreme right and their politics.”

The US and the settlers

The US says it opposes the creation of settlements and has recently sanctioned bodies involved with the movement, some known to be close to Ben-Gvir and said to be actively fundraising for the settler movement within the US.

The US government has also said it is considering sanctions against the Netzah Yehuda battalion, which operates within the occupied West Bank and draws its recruits from Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews, on repeated allegations of rights abuses.

Nevertheless, while the US may oppose settlements on paper, the Israeli government publicly embraced the settler mission of Ben-Gvir and Smotrich in June of last year, overturning legislation that had stood for 27 years, and giving Smotrich effective control of the expanded and accelerated settlement-building process. Netanyahu himself has repeatedly rejected the idea of a Palestinian state, and has presented himself as a bulwark against Palestinian self-determination.

Other than a brief period under former President Donald Trump, when the United States supported the notion of settlements, Washington has regarded them as illegal since 1978. In 1983, the census showed that the settler population of the West Bank was 22,800. It is currently estimated at 490,493.

And now, that dominance of the settler ultranationalist trend in Israeli politics threatens Gaza.

At a “Settlement Brings Security” conference in Jerusalem in January, around a third of Netanyahu’s cabinet ministers, as well as up to 15 additional Knesset members, including members of his own nationalist Likud Party, walked past a large map of Gaza with a bold star of David emblazoned above it.

For Palestinians in Gaza, the threat of a new wave of displacement to make way for any such illegal settlement is real – championed by figures at the very top of Israeli politics.

Politics

With capital gains change, the Liberals grasp the tax reform nettle again – CBC News

In the fall of 2021, the editors of the Canadian Tax Journal devoted several dozen pages to the “hotly debated” topic of capital gains.

On balance, the editors wrote, their selected contributors were in favour of raising the inclusion rate for capital gains — the share of an individual’s capital gains that are subject to income tax rates. But they acknowledged that putting such a change into practice would not be easy.

“Opposition to capital gains tax increases among affected taxpayers is apt to be vociferous,” Michael Smart and Sobia Hasan Jafry wrote in one of the featured papers, “precisely because such a reform would act like a lump sum tax that would be difficult or impossible for taxpayers to avoid in the long run by changing their behaviour.”

Whatever its exact causes or motivations, “vociferous” opposition to tax hikes may be as old as taxation itself. But the Liberals already have firsthand experience of how loud that opposition can get, having watched one set of reforms struggle to survive an onslaught of confusion and controversy in the summer of 2017.

Now they’re taking another swing at it — and one big question is whether they’re better prepared for the blowback this time.

The federal government unveiled billions in spending in its 2024 budget, and to help pay for it all, it’s proposing changes to how capital gains are taxed. CBC’s Nisha Patel breaks down how it works and who will be affected.

If the Liberals are hoping to look reasonable and measured, they can at least point to the fact that they haven’t gone nearly as far as some wanted them to go.

In their 2001 paper, Smart and Hasan Jafry proposed increasing the inclusion rate from 50 per cent to 80 per cent for all capital gains. In her third budget, tabled last week, Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland proposed an inclusion rate of 67 per cent for capital gains of $250,000 or more.

In their 2021 analysis, Smart and Hasan Jafry pointed out that the wealthiest families benefited disproportionately from the preferential tax treatment afforded to capital gains (though there is some debate over exactly how disproportionately the benefits are distributed). That’s now a key aspect of the government’s argument.

“The government is asking the wealthiest Canadians to pay their fair share,” last week’s budget document said, adding that only about 0.13 per cent of Canadians would be affected by the change.

As Freeland noted, her changes also aren’t unprecedented. From 1990 to 2000, the inclusion rate was 75 per cent for all capital gains. Freeland is also promising a special carve-out aimed at entrepreneurs.

“There are a lot of reasons why the inclusion rate should go up for capital gains,” Smart said in an interview this week.

For one thing, Smart argues, “it’s fairer for all Canadians if taxpayers with capital gains pay the same rates of tax as the rest of us do right now.” Also, he says, “it’s better for the economy if every investor is paying the same tax rate on everything she or he invests in,” pointing to differences in the way dividends and capital gains are taxed.

The fight over what these changes will mean

While condemning the budget, Pierre Poilievre’s Conservatives have been noticeably quiet on the issue of capital gains. That might be because they sense — correctly — that the Liberals would be happy to accuse them of supporting tax breaks for the rich.

For the time being, other voices are filling the void — including doctors, who came forward with their own concerns this week. The technology sector has been the loudest in its objections. The Council of Canadian Investors has sponsored an open letter that has now been signed by hundreds of tech executives.

Canadian Medical Association president Dr. Kathleen Ross tells Power & Politics that she fears changes to the capital gains tax will make recruitment and retention of physicians more difficult at ‘a time where the health force is beleaguered, mothballed and really struggling to deliver on services to Canadians.’

In an op-ed for the National Post, the council’s president, Benjamin Bergen, warned that the changes would hurt Canada’s economic “vibes.” Specifically, he argued that a higher inclusion rate would discourage business investment.

“Capital gains are taxed at a different rate because they are taxes on investment,” he wrote. “Every investment comes with risk … [t]he tax code takes this into account.”

But other figures in the investment community have come forward to say the backlash is confused and unwarranted.

There does not seem to be a clear consensus on the economic impact of changes to the capital gains tax. In a paper published last year, the economist Jonathan Rhys Kesselman wrote that “the overall impact of existing and increased capital gains taxes on the economy’s efficiency and growth are mixed and not easily quantified.”

“When the gains inclusion rate was raised to 75 per cent in 1990 for nearly a decade, adverse economic impacts were not observed, though this is at best weak evidence,” Kesselman wrote. “Contrary to common claims about higher taxes on gains, some impacts would be economically favourable, and others that might be adverse could be mitigated through appropriate concomitant reforms.”

All in a Day13:14Three tech entrepreneurs break down impact of federal budget on their sector

Ottawa tech pros want the federal government to reconsider capital gains changes that, they say, can scare investors and jeopardise business.

It might be fair to assume the change will have some downside. But every policy choice involves a trade-off.

In an email this week, University of Calgary economist Trevor Tombe — who argues it makes sense to hike taxes on capital gains — wrote that while it would not be controversial to suggest the capital gains changes will have some kind of negative effect, “all policy choices come with costs and benefits, so we also have to then compare the costs to the benefits of the government’s spending choices.”

What the Liberals might have learned from 2017

Compared to the tax fight of 2017 — when the Liberals sought to change the rules on private incorporation — the government has been far more explicit and purposeful this time about connecting the tax changes to new spending proposals, particularly those related to ensuring that younger Canadians can find affordable places to live.

“I understand for some people this might cost more if they sell a cottage or a secondary residence, but young people can’t buy their primary residences yet,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Tuesday.

In total, the changes are projected to produce $19.4 billion in additional revenue for the federal government over five years. In her budget speech, Freeland connected asking wealthy Canadians to pay more with federal programs to provide dental care, school lunches and free contraception.

The goal of reducing income inequality might be worthy in and of itself, but it’s more abstract than the tangible things the Liberals are pointing to now.

An internal review conducted by the Finance Department after the tax storm of 2017 concluded that the government had been slow to respond to concerns and criticism and that there was a “need to more rapidly adjust communications strategies and messaging to effectively address misconceptions.” Scott Clark, a former senior finance official, observed at the time that there were no “winners” — people who would benefit from the changes — to whom the federal government could point.

The early returns might suggest the government learned some things from the 2017 experience. For one thing, Freeland openly acknowledged from the outset that some people were likely going to be upset.

But if 2017 is any guide, the opposition is unlikely to pass quickly or quietly.

Politics

Meet Shannon Waters, The Narwhal’s B.C. politics and environment reporter – The Narwhal

When Shannon Waters first joined the press gallery at the B.C. legislature, the decision on whether or not to continue the Site C dam project was looming large. Shannon was there as a reporter for BC Today, a daily political newsletter, and she remembers being blown away by long-time Narwhal reporter Sarah Cox’s work.

“Her ability to look at these huge complex reports, which, at the time, I mostly just felt like I was drowning in, and cut through that to tell stories about what was really going on was impressive,” Shannon says. “That was my initial intro and I have been following The Narwhal ever since!”

Fast forward more than six years later, Shannon joins The Narwhal as our first-ever B.C. politics and environment reporter. And get this, Sarah will be her editor in the new gig.

“After years of admiring their work, I’m excited to work with Sarah and the whole Narwhal team,” Shannon says.

I sat down with Shannon to get to know her better and hear more about what brought her The Narwhal’s growing pod.

What’s your favourite animal?

That’s easy, it’s an octopus. I have one tattooed on my arm. I just think it’s really neat that we have a creature on this planet as intelligent as an octopus. It’s the closest thing to alien life that we’ve ever come across but it’s right here on the planet with us. And I think that’s very cool.

What is the thing about journalism that gets you excited to start your work day?

I get excited about working as a journalist because every day is a bit different. I like having the opportunity to learn new things on a regular basis, partly because I get bored really easily.

My favorite thing about being a reporter is you never really know exactly how your day is gonna go and you’re always getting to talk to interesting people. As a bonus, I also really like to write, and I always have.

Your first job was at a radio station in Prince George, B.C. How did this early experience shape you?

I think it really honed my sense of journalism being part of the community and a community service. We covered all kinds of things. I was on the school board beat when I first got there and then I was covering city hall a little later on. I did a weekend shift. I covered crime stories.

Sometimes you’d start out the day covering one story and then by the end of the day, you’d be doing something else. I was also in Prince George in 2017, for the wildfires, and the city became a hub for people who were displaced from all across B.C. That was a really intense, eye-opening experience about what communities can do for people when they are put to the test. So again, learning things, and that variety and getting to write about them for a living.

You’re a self-described political nerd. Where does that come from?

I’m fascinated by politics because it touches every aspect of our lives, and there’s not really any way to get away from it. I consider myself a bit cynical about our political systems but even if you don’t like them, or don’t believe in them, or don’t want anything to do with them, you can’t really get away from politics. I find it fascinating to look at what is going on in the political sphere, what kind of policies are popular at the moment? Which ones are being rejected? How is that conversation going? How did it get started? Where might it go? And politics is also about people.

I like being someone who can hopefully try and help people understand why politics matters, what they can do to try and affect the change that they might want to see and how the politics in their area or the policies being enacted by politicians affects them and the people around them. It’s not something that everybody finds fascinating. A lot of people’s eyes glaze over when you tell them you’re a political or a legislative reporter. But I really enjoy the work. And it’s one of those things that feels like, well, somebody should be doing it. And so for now, at least, that somebody can be me.

It’s an election year in B.C. What are you most excited about?

I’m looking forward to seeing what happens. We’re really in a very interesting space in B.C. right now. If you were talking to me a year ago about the election, I would probably have sounded a bit more bored, because it seemed like much more of a foregone conclusion — you know, the NDP were going to likely win a majority and we’d have sort of more of the same. But now you have this really interesting churn in the political landscape with the emergence of the B.C. Conservatives as a real contender of a party according to the polling that we’ve been seeing. Meanwhile B.C. United, which is the very well-established B.C. Liberal party renamed, has sort of had the wheels come off.

So, I’m really interested to see what happens on the campaign trail as you have these parties trying to court voters, what sort of ideas they’re going to put forward. I’m also really curious what it means for the Green Party. B.C. hasn’t had a lot of elections where we’ve had so many parties competing for seats in the legislature and I think that’s going to make for a very interesting and probably quite dramatic campaign.

What kind of stories do you hope to tell more of?

I am excited about getting more in depth. I’ve been doing daily news for about seven years now, including covering elections. I have really enjoyed doing that and I feel like when you’re a daily news reporter you also have all these thoughts about potential stories that need a closer look or more time to percolate. So I’m really looking forward to looking at the news landscape and seeing what’s missing. With the election, I’m also excited to look back and think: what was the government saying about this particular policy in the last election? What have they done on it during the interim? And what are they saying now?

I think one of the biggest things I learned as BC Today’s reporter and later Politics Today’s editor-in-chief is finding the stories in the minutia and the nuts and bolts of what goes on in the legislature. There’s a list that has been building in my head for a long time of all of these stories that I’ve wanted to take a closer look at over the years and I’m excited to get started.

What are three things people might not know about you?

I could eat peanut butter toast and drink coffee every day of my life and die happy. Growing up I wanted to be a marine biologist and study either sharks or cephalopods. I am the biggest word nerd, which can be a good thing for someone who writes for a living, but is sometimes a struggle. I am still striving to use the word “absquatulate” in a story someday!

-

Politics23 hours ago

Politics23 hours agoOpinion: Fear the politicization of pensions, no matter the politician

-

Science23 hours ago

Science23 hours agoNASA Celebrates As 1977’s Voyager 1 Phones Home At Last

-

Politics22 hours ago

Politics22 hours agoPecker’s Trump Trial Testimony Is a Lesson in Power Politics

-

Media16 hours ago

B.C. online harms bill on hold after deal with social media firms

-

Media22 hours ago

B.C. puts online harms bill on hold after agreement with social media companies

-

Business22 hours ago

Oil Firms Doubtful Trans Mountain Pipeline Will Start Full Service by May 1st

-

Art24 hours ago

Turner Prize: Shortlisted artist showcases Scottish Sikh community

-

Media21 hours ago

Trump poised to clinch US$1.3-billion social media company stock award