CNN

—

The lesson of January 6, 2021, is that when extremism, conspiracies and incitement reach a boiling point, they seek an outlet.

That recent history is loudly echoing amid a deepening sense that the country could be heading back to a dark political place as another Election Day looms. And sadly, in a such a toxic age, another violent eruption cannot be ruled out.

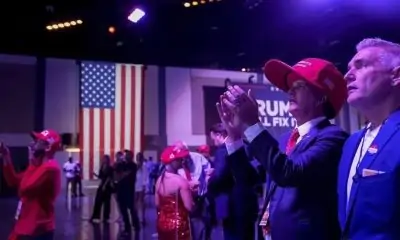

As he contemplates a 2024 campaign and rallies for 2022 candidates, ex-President Donald Trump is conducting a new symphony of political malice and facing little pushback from his party despite the insurrection’s example of where the politics of malevolence can lead.

The foreboding atmosphere five weeks before the midterm elections shows the country remains in the grip of the rancor that stained the peaceful transfer of power from one president to another less than two years ago.

Trump launches direct attack on McConnell a month out from midterm elections

This coincides with painful and far from complete investigations into what happened after the 2020 election. On Monday, for instance, on the first day of the trial of five alleged members of the Oath Keepers militia charged with seditious conspiracy, jurors heard how senators cried as they hid from Trump’s mob.

The former President dialed up the hate another notch last week with a social media post that accused Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, with whom he has a strained relationship, of having a “death wish” and flung racism at his wife, former Transportation Secretary Elaine Chao. In another escalation, Trump recently slammed FBI agents as “vicious monsters” over the lawful search of his Florida home.

One of the ex-President’s top boosters, Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene of Georgia, also played into Trump’s politics of fear at his weekend rally in Michigan, claiming that Democrats wanted Republicans dead.

Trump’s political model remains rooted in igniting anger among his supporters. The more outrageous his comments, the more that the ex-President and his supporters show disdain for Washington elites and the rules and conventions that constrain the presidency and government institutions. His political self image emulates the militarism and brashness of foreign strongmen. And in a sense, his refusal to temper his political speech, even at the risk of endangering others, demonstrates yet again his power over a party that largely refuses to rebuke him, however extreme he becomes.

Attacks on or threats to political leaders are not just a bloody relic of America’s past. There have been multiple recent instances of intimidation targeting political figures from both parties – from death threats left on Illinois GOP Rep. Adam Kinzinger’s phone over his involvement in the House’s insurrection probe to charges filed against a man who allegedly harassed Democratic Rep. Pramila Jayapal of Washington state.

In June, a man was charged with attempting to kill Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh. The same month, New York Republican Rep. Lee Zeldin, who’s running for governor, was attacked by a man at a campaign event. While the alleged assailant appeared not to have a political motive, it was a reminder, as if one was needed, of the vulnerability of candidates on the stump.

Former Democratic Rep. Gabrielle Giffords of Arizona was left with life-changing injuries by a gunman who attacked a constituency event in 2011, killing six people. In 2017, Louisiana GOP Rep. Steve Scalise was badly wounded by a gunman who opened fire at a congressional baseball practice. The man had professed support for Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders’ progressive politics and hated conservatives and Trump, according to a CNN review of his Facebook profiles, public records and letters to his newspaper. (Sanders, who has never employed the kind of incitement that Trump is known for, was quick to condemn the shooting as “despicable” after saying the assailant “apparently” volunteered for his presidential campaign, and he made clear violence of any kind was unacceptable.)

Why you can’t just ignore Donald Trump’s latest threat

It’s not always possible to trace each attack, or attempted attack, to specific heated rhetoric. But such incidents also mean that politicians cannot claim their words are uttered in a vacuum. The dangers of stoking fear and violence are obvious. The US Capitol insurrection made this clearer than ever. Multiple rioters testified in court cases that they were doing what Trump wanted on that day. In the House select committee’s seventh hearing, Stephen Ayres, who pleaded guilty to disorderly conduct in a restricted building, said everyone was simply following what the former President wanted. Or as the panel’s vice chair, Wyoming GOP Rep. Liz Cheney put it, the then-President “summoned the mob, assembled the mob and lit the flame of this attack.”

In a nation with easy access to guns, with a recent history of political violence and where Trump and others use false claims of voter fraud as political rocket fuel, it is reasonable to wonder what dire consequences may haunt this election season.

Mississippi Democratic Rep. Bennie Thompson, who chairs the House select committee, on Monday condemned Trump’s social media assault on McConnell and told colleagues in both parties, “We need to be better than this.”

He said in a statement that Trump’s rhetoric “could incite political violence, and the former President knows full well that extremists often view his words as marching orders.”

In an editorial on Monday, the conservative editorial page of The Wall Street Journal also condemned Trump’s attack on McConnell.

“The ‘death wish’ rhetoric is ugly even by Mr. Trump’s standards and deserves to be condemned. Mr. Trump’s apologists claim he merely meant Mr. McConnell has a political death wish, but that isn’t what he wrote,” the paper said.

“It’s all too easy to imagine some fanatic taking Mr. Trump seriously and literally, and attempting to kill Mr. McConnell.”

A New York Times story over the weekend, which detailed a stream of threats and harassment against lawmakers of both parties, noted that after Trump was elected in 2016, the number of reported threats against members of Congress rose more than 10 times to 9,625 in 2021, according to Capitol Police figures.

“I wouldn’t be surprised if a senator or House member were killed,” Republican Sen. Susan Collins of Maine told the paper in an interview.

“What started with abusive phone calls is now translating into active threats of violence and real violence.”

Violent rhetoric can be bipartisan. But there is little doubt that Trump’s behavior has contributed to an increasingly volatile political culture.

Long before the Capitol insurrection, the ex-President injected a bullying and brutal tone in his campaign rhetoric. Month by month, Trump built an impression that violence was a legitimate tool of expressing political grievances – a process that came to a head on January 6 – and further eroded the idea that Americans’ differences should be settled at the ballot box rather than through violent action.

‘It’s never, ever OK to be a racist,’ Rick Scott says when asked about Trump’s personal attack on Elaine Chao

The former President appears to implicitly offer his supporters a kind of permission to emulate his incitement. And his tendency to drag others down into the political gutter with him has contributed to a coarsening of the wider political culture, especially among Republicans who have to choose between their political careers and publicly tolerating his extremism.

Republicans often seize upon the rhetoric of key Democratic figures to suggest their supporters are being victimized and targeted. This happened most recently when Biden referred to Trump’s “Make America Great Again” supporters as embracing “semi-fascism.” Intemperate political rhetoric should always be condemned. But any objective viewing of Trump’s speeches and social media posts must conclude that he’s an incessant and deliberate offender.

Part of the reason why is that his own party – some courageous lawmakers aside – almost never steps into condemn him. This was borne out by the uncomfortable dodging from Florida Sen. Rick Scott, the chairman of the Senate GOP campaign committee, on Sunday shows when he was asked to condemn Trump’s post about McConnell.

“You know, the President likes to give people nicknames. So you can ask him how he came up with a nickname. I’m sure he has a nickname for me,” Scott told CNN’s Dana Bash on “State of the Union,” before struggling to reorient the conversation toward the high inflation that Republicans believe will hurt Democrats in the midterms.

“I hope no one is racist. I hope no one says anything that’s inappropriate,” Scott said, encapsulating the manner in which Trump has intimidated his party into submission through seven years of fury since he announced his first campaign.

As the former President cranks up his political machine again, and as the broader political environment deteriorates, a sense of menace and danger is again gathering around another American election.

Source link