Art

Vancouver Art Gallery's fall lineup shows there's more to Victor Vasarely's universal visual language – Ubyssey Online

A huge print of David Bowie’s self-titled album cover. Neon tubing inside the frame of a painting. A tube-shaped sculpture made of suspended rice paper. What do these all have in common?

The fall exhibition lineup for the Vancouver Art Gallery.

On October 17, three new exhibitions opened at the Vancouver Art Gallery: Victor Vasarely, Op Art in Vancouver, and Uncommon Languages. Op Art in Vancouver was developed in conjunction with Victor Vasarely, while Uncommon Languages responds to themes throughout Vasarely’s work, specifically that of a “universal visual language.”

So this review is a buy one get two free. Lucky you!

Victor Vasarely

Imagine you’re standing in front of a huge painting. Taller than you, if you were the approximate size of, say, a 5’5” man. The painting is of a grid. Small black diagonal squares — like they’ve been italicized — against a white background.

Except some of the squares are going the wrong way. No matter how long you look at it, your eyes keep going back to those squares, the ones that are pointed in the opposite direction as the rest. There isn’t a pattern of directions reversed. There are just three splotches of nonconformity. But it makes the whole painting jump; you can almost see a weird moving S shape in the grid of squares — except there definitely isn’t one. You’re seeing things.

That’s Vasarely, baby.

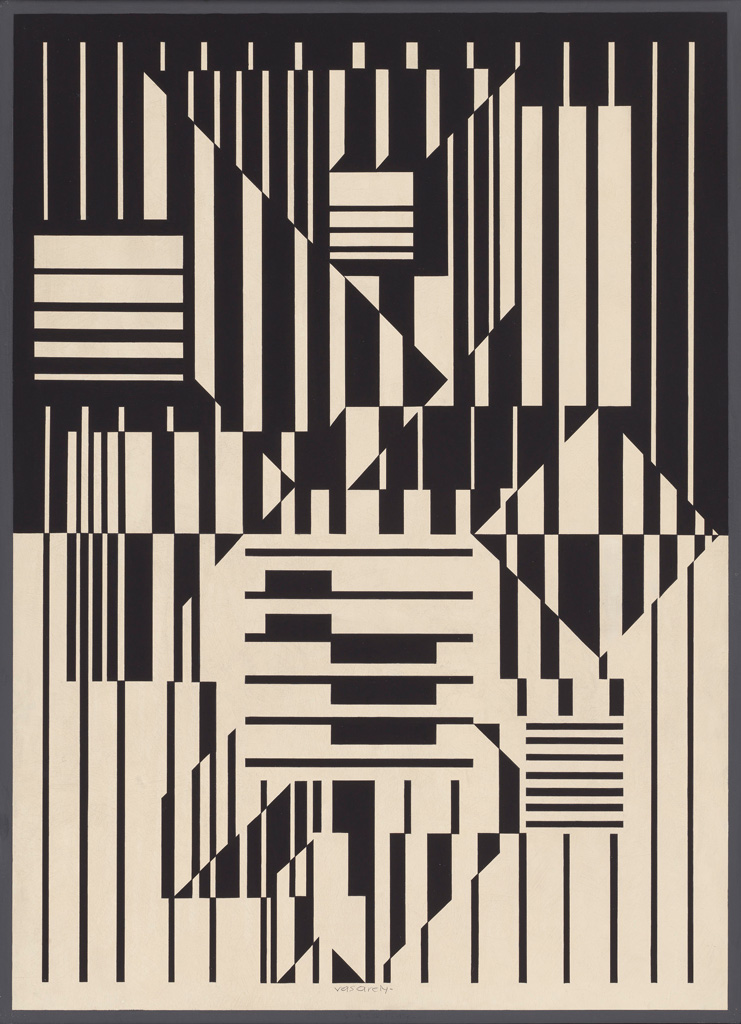

Victor Vasarely was a Hungarian-French artist renowned for his colourful abstract patterns and largely credited as being the father of the Op art movement. Op art, short for optical art, is simply art that plays with optical illusions.

When I think of optical illusions, I jump past pieces that invoke movement or depth in a completely still 2D surface. I tend to look for works which make you squint really hard to see the young woman instead of the old lady. To be fair, those are both optical illusions. But this exhibit, which focuses on Vasarely’s work from the 1960s and ’70s, is much more the former.

It’s simplistic and highly abstract. Shapes and colours.

Vasarely worked with such simple shapes and a limited palette for a straightforward reason: he wanted to create a universal visual language. Like, really wanted. Victor Vasarely doesn’t just contain paintings. There are sculptures, books, an album cover, a tea set, screenprints, a mass-produced woven piece and what basically amounts to a board game. (Called Planetary Folklore, it’s basically a build-your-own-Vasarely kit, with patterns matching his actual pieces.)

Despite his impressive breadth of mediums, the pieces I kept returning to were his paintings. I think it’s the scale that gets to me. From far away, they look simple and clean, experiments in design and colour.

But if you get close enough, you can still see the brushstrokes; the medium betrays the presence of the artist.

Sorry, Vasarely. There’s no universality. It’s all just you, all the way down.

Op Art in Vancouver

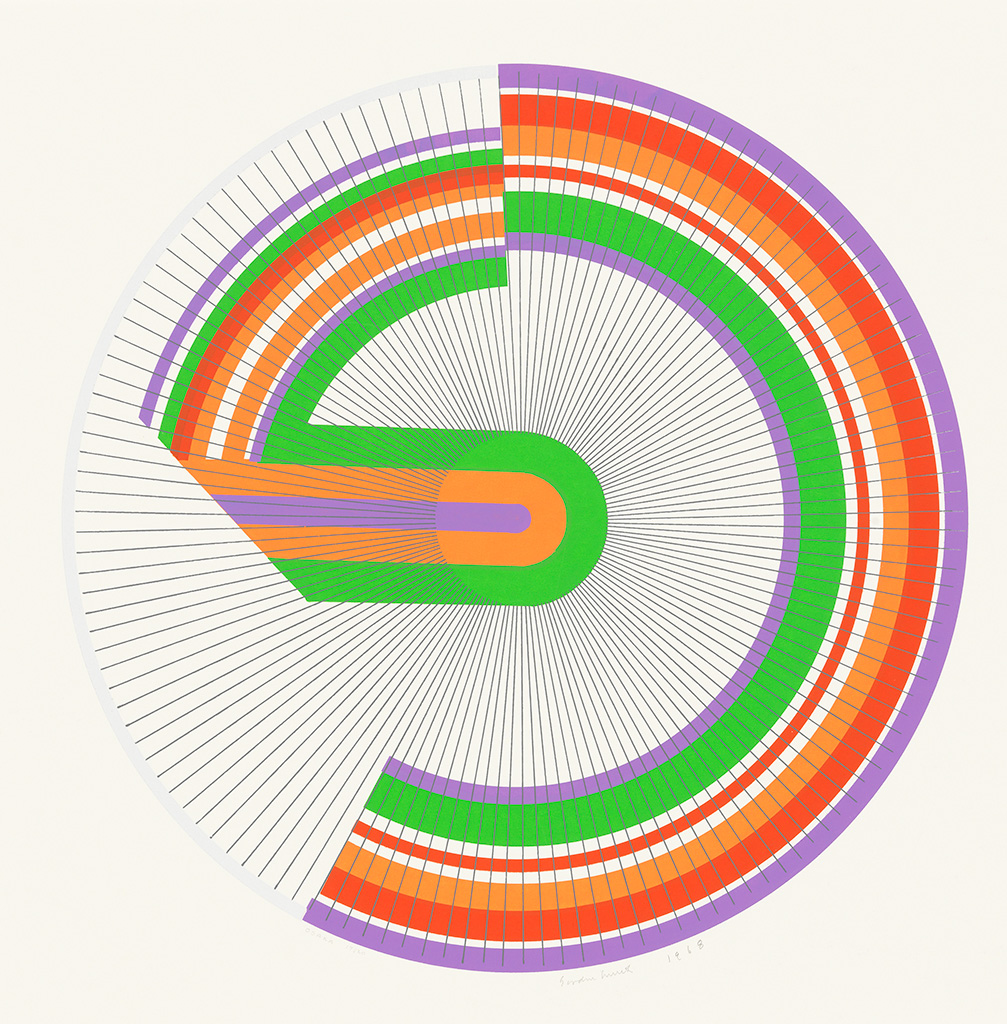

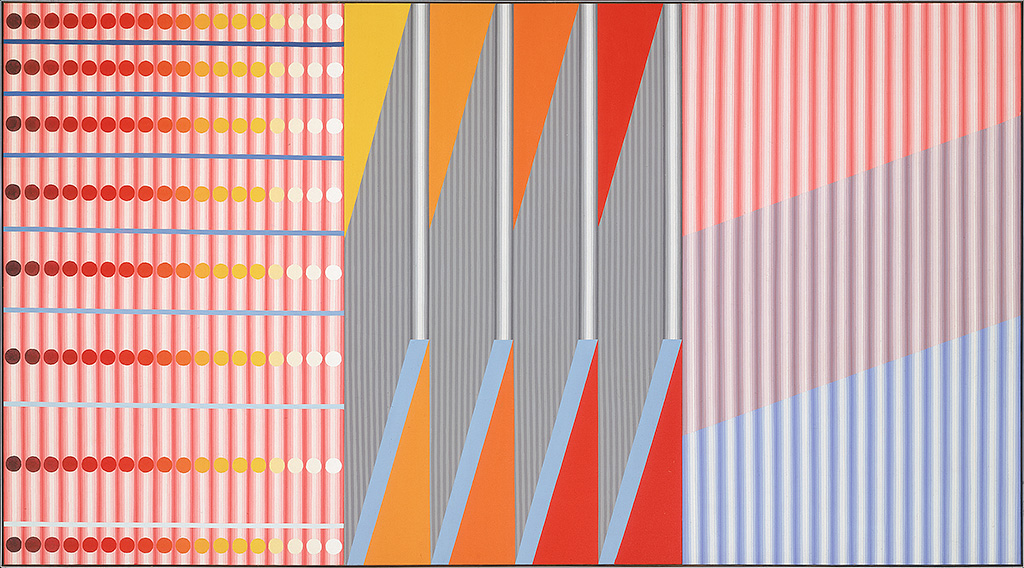

Unsurprisingly, Op Art in Vancouver is about the emergence of Op Art in Vancouver during the late 1950s and early ’60s. This small exhibition is the bridge between Victor Vasarely and Uncommon Language — quite literally because you have to walk through it to get from one exhibit to the other.

While the pieces in Vasarely played with literal optical illusions to convey a sense of movement or depth, the Op-art here is just as concerned with challenging what the viewer expects to see as it is with challenging how the viewer sees.

Which is to say: most of the pieces in Op Art in Vancouver are paintings or screenprints — weird ones. (Neon tubing! Mirrors! Mirrors in the paintings!)

In fact, there’s this fun divide in Op Art in Vancouver between pieces that are noticeably visually jarring and pieces that look essentially identical to contemporary graphic design.

With digital art software, straight lines and solid colours are easy, or at least, easier than they are with paint on canvas. Which is, in itself, something a lot of people don’t think about often, because straight lines and solid colours are meant to look easy.

Why am I so emotional about straight lines? Michael Morris, that’s why.

Michael Morris is one of the artists in Op Art in Vancouver. The thing that set Morris’s work apart for me — aside from the mirrors and plexiglass — was the fact that, unlike a lot of his peers, Morris painted without the aid of masking tape and paint rollers, which were used to create the sharp lines and smooth surface that feels so graphic design-y about op art.

The lines in Morris’s work wobble. They’re clearly and visibly imperfect. Yet his design compositions are just as abstract and shape oriented as his counterparts in Op Art in Vancouver. It’s surreal as hell to look at. I highly recommend looking at it.

Uncommon Language

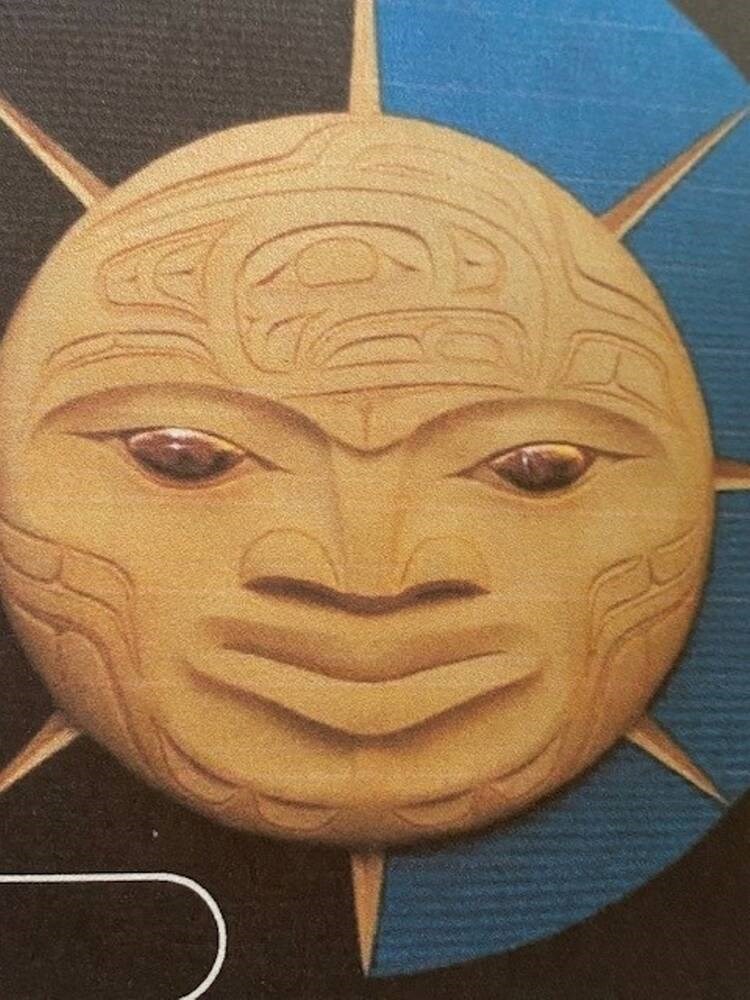

Uncommon Language is the third exhibition in the Vancouver Art Gallery’s fall lineup and the most visually distinct. Quite simply, it’s not op art. While Op Art in Vancouver explores how Op art traditions emerged locally, Uncommon Languages addresses the thematic undertones of Vasarely’s work, specifically his desire for a universal visual language.

But, once you think about it, the concept of a universal visual language is, in a lot of ways, not all that utopian. In fact, it’s deeply Eurocentric, not to mention colonialist. You idealize the concept of a single universal language when society’s standards of “universal” have always included you.

Uncommon Language is a broad and vast exhibition in subject, medium and tone. There’s a marble bench, several poems, a mask, a painting leaned against the wall, a row of books painted black, spliced-together videos of people exercising — it’s a lot.

The pieces here not only expand on a desire for universality and question whose voices are and aren’t being heard, they also challenge the viewer’s expectations of art, similar to op art. It’s just more … conceptual. Like, if we lean a painting against a wall instead of hanging it up, how does that change how we approach the painting?

I agree. That question sounds incredibly conceited when I say it like that. But I also can’t describe how physically uncomfortable it was to see Andrew Dadson’s Black Lean Painting.

Even though Uncommon Language plays with thematic disruption and visual disruption, there is a third, more subtle layer of disruption going on, which is clearest to see in the presentation of Françoise Sullivan’s Dance in the Snow.

Dance in the Snow is a series of photographs of Sullivan performing a dance routine that only three people ever saw. (It was filmed, but the film was lost.) The photographs that comprise Dance in the Snow are presented next to an essay by Sullivan about the dance, published on the 30th anniversary of its single performance.

But the most riveting part of seeing this piece in Uncommon Language is the historical context that the didactic text — the gallery wall text — provides. This is context that Sullivan is deliberately not addressing in her work, or her reflection on her work, like how one of her dance instructors was known for appropriating African dance movements and percussion, or how Sullivan herself positions her reflection on this dance within colonialist tropes of being alone in a landscape.

Uncommon Language pulls a lot of big, theoretical punches. It’s a deeply thought-provoking exhibition.

But mostly, I wondered why it wasn’t the exhibition literally named after and focused on the works of Victor Vasarely that contextualized his desire for a universal visual language in the historical context of ongoing colonialism. Why it didn’t attempt to contextualize his work in any historical context aside from his fame in the 1960s and ’70s? Why it framed his use of mass production to make artwork more available as revolutionary, instead of, you know, deeply consumerist.

Is it a disservice to present something as simple when it’s actually complex? How much of a disservice, if at all? What might Victor Vasarely and Op Art in Vancouver have gained from talking about their historical contexts within those exhibitions?

I don’t know. But I wonder.

Victor Vasarely, Op Art in Vancouver and Uncommon Language will be open until April 5, 2021.

Art

Art in Bloom returns – CTV News Winnipeg

Art

Crafting the Painterly Art Style in Eternal Strands – IGN First – IGN

Next up in our IGN First coverage of Eternal Strands, we’re diving into the unique and colorful art in the land of the Enclave. We sat down with art director Sebastien Primeau and lead character artist Stephanie Chafe to ask them all about it.

IGN: Let’s talk about Eternal Strands’ distinctive art style. What were some of the guiding principles behind the art direction?

Primeau: I think what was guiding the art direction at the beginning of the project was to find the scale of the game, because we knew that we were having those gigantic 25-meter tall creatures and monsters. So we really wanted to have the architectural elements of the game – the vegetation, the trees – to reflect that kind of size.

So one of my inspirations was coming from an architect called Hugh Ferriss, and I was very impressed by his work, and it was very inspiring for me too. So just the scale of his work. So he was a real influence for Metropolis, Gotham, so I was really inspired by his work.

Chafe: I think one of the things that, just as artists and as creators, we were interested in as well was going for a color palette that can be very bright. And something that can really challenge us too as artists, and going into a bit more of at-hand painterly work, and getting our hands really into it, into the clay, so to speak, and trying to go for something bright and colorful.

IGN: That’s not the first time I’ve heard your team describe the art style as “painterly.” What does that mean?

Primeau: Painterly is just a word that can give so much room to different types of interpretation. I think where we started was Impressionist painters. So I really enjoy looking at many painters, and they have different types of styles. But we wanted to have something that was fresh, colorful, and unique.

And also, I remember when we were starting the project there was that word. “It’s going to be stylized,” but stylized is just a word that gives so much room to different kinds of style. And since we were a small team, we had to figure out a way to create those rough brushstrokes. If it was painted very quickly by an artist, like Bob Ross would say, “Accident is normal.” So I think we wanted to embrace that. And because we’re all artists, it’s hard too, at some point, to disconnect from what you’re doing. It’s like, “Oh, I can maybe add some more details over there.” But I was always the- “Guys, oh, Steph, that’s enough. Let’s stop it right there. I think it looks cool.”

IGN: So, when you create an asset for Eternal Strands, is somebody actually painting something?

Chafe: I can speak more on the character side. For us, we do a lot of that hand painting, a lot of those strokes by hand. And we try to embrace, not the mistakes, but the non-realistic part of it having an extra splotch here and there.

We’ve got brushes that we made that can help us as artists to get the texture we’re looking for. It really is a texture that gives to it. But a lot of the time it’s not just something generated in a substance painter, or getting these things that will layer these things for you, making it quick and procedural. Sometimes we have those as helpers, but more often than not we just go in and paint.

IGN: Eternal Strands is a fair bit more colorful than lots of games today. Why was it important to the team to have lots of bright colors?

Primeau: You need to be careful, actually, with colors. Because with too many colors you can create that kind of pizza of color.

We wanted to balance the color per level, because we’re not making an open-world game. I really wanted each level to have their own color palette identity. So we’re playing a lot with the lighting. The lighting for me is key. It’s very important. You can have gorgeous textures, props, characters, but if your lighting is not that great, it’s like… So lighting is key. And especially with Unreal Five, we have now, access to Lumen. It brought so much richness to the color, how the color is balancing with the entirety of the level. It definitely changed the way we were looking at the game.

We’re using the technology, but in a way to create something that feels like if you were looking at a painting. I think we have achieved that goal.

Chafe: I’m very happy with it.

IGN: What were your inspirations from other games or other media when developing the art style?

Primeau: I have many. I’ll start with graphic novels, European graphic novels. I really wanted to stay away from DC comics, Marvels comics, those kinds of classics.

Before I started Eternal Strand, I saw a video. It was one of the League of Legends short films for a competition. It’s “RISE.” I don’t know if you remember that one, but it was made by Fortiche Studio who did Arcane, and I’m a huge fan of Arcane. When I saw that short film, it was way before Arcane was announced, I was like, “oh gosh, this is freaking cool. This is so amazing. I wish I would be able to work on a game that has that kind of look.”

Chafe: For me, when we started the project, one of the things that I wanted to challenge myself a lot was in concept and drawing and stuff like that and doing more, learning more about color as well, which is something I find super fascinating and also kicks my butt all the time because of just color theory in general.

But with the [character] portraits specifically, I think, I mean, growing up I played a lot of games, a lot of JRPGs too. I played just seeing basic portraits in something like Golden Sun or eventually also Persona and of course Hades, which is a fantastic game. I played way too much of that, early access included. But I really liked that part. Visual novels too, just that kind of thing. You can get an emotion from a 2D image as well when it’s well done, especially if you have voices on top of it.

IGN: Were there any really influential pieces of concept art that served as a guiding document the team would reference later on?

Chafe: I have one personal: It’s really Maxime Desmettre’s stuff because it was so saturated. Blue, blue, blue sky. Maxim Desmettre is our concept artist that we have who works from Korea. When I joined the project, seeing that was just like… and seeing that as a challenge too, like ‘how are we going to get there?’

The one that I’m thinking of that hopefully we could find after, just in general with the work that always speaks so much to me is this blue, blue sky and the saturation of the grass. But also when he gets into his architecture and stuff like that, there’s just a warmth to everything. The warmth to the stone that just makes it look inviting and mysterious at the same time. And I think that really speaks a lot to it.

IGN: How did you go about designing Eternal Strand’s protagonist: Brynn?

Primeau: I think that Mike also, when he pitched me the character, he was using Indiana Jones as an example. So courageous, adventurer guy, cool guy. Also, when you’re looking at Indiana Jones, he’s a cool guy. And we wanted to create that kind of coolness also out of our main protagonist. And I remember it took time. We did many iterations.

Chafe: It was a lot of iterations for sure. Well, I think I had done a bunch of sketches because it’s what’s going to be the face of the player, and also to have her own personality as well in the story, and her history as well. And the mantle was a really big one too. What gives her one of sets of her powers and stuff, figuring that out was actually one of the longest processes. It’s just a cape, but at the same time, it’s getting that to work with gameplay and all that kind of stuff. But yeah, all of Brynn’s personality and her vibe really comes from a lot of good work from the narrative team. So, mostly collaboration there.

IGN: What’s the deal with Brynn’s mentor: Oria? How did you settle on a giant bird?

Chafe: Populating the world of the enclave was, “it’s free real estate.” You get to just throw things on the wall and see what sticks. And, “Oh, that’s really cool. Oh, that’s nice.” At some point I’d done a big sketch of a big bird lady with a claymore, and Seb said, “That’s cool.” And then kind of ran with it.

IGN: What’s the toughest part about the art style you’ve chosen for Eternal Strands?

Primeau: The toughest part was…A lot of people in the team have experience making games, so it was to get outside of that mold that we’ve been to.

For me, working on games that were more realistic in terms of look, I think it was really tough just to think differently, to change our mindset, especially that we knew that we would be a small team, so we had to do the art differently, find recipes, especially when we were talking about textures, for example. So having a good mix.

Chafe: One of the things too is also as we’re all a bunch of artists, and every artist has their own style that they just suddenly have ingrained in them, and that’s what makes us all unique as artists as well. But when you’re on a project, you have to coalesce together. You can’t kind of have one look different from the other. When you’re doing something more realistic, you have your North Star, which is a giant load of references that are real. And you can say “it has to look like that, as close to that as possible.”

When you have a style in mind and you’re developing at the same time, you kind of look at it and you review it and you have a feeling more than anything else.

You’re training each other with your styles as you kind of merge together in the end. And that kind of is how the style happened through, like you mentioned, like finding easy recipes, through just actually creating assets and seeing what comes out and, “Oh, that’s really cool. Okay, we can now use that as kind of our North Star.”

For more on Eternal Strands, check out our preview of the Ark of the Forge boss fight, or read our interview with the founders of Yellow Brick Games on going from AAA studios to their own indie shop, and for everything else stick with IGN.

Art

Collection of First Nations art stolen from Gordon Head home – Times Colonist

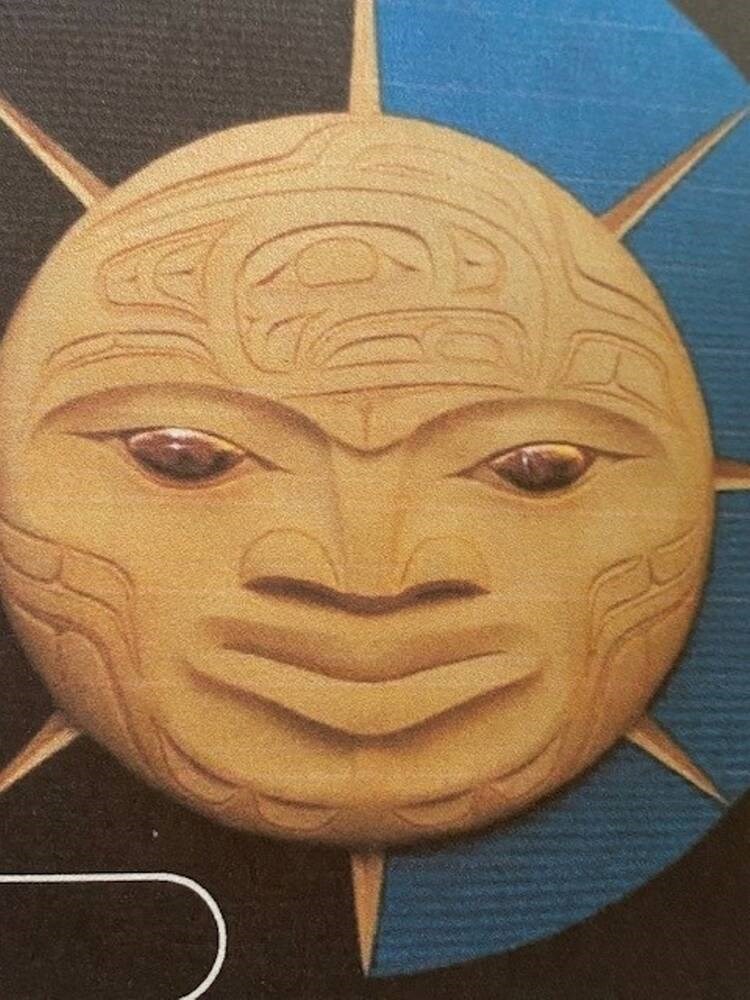

Saanich police are investigating the theft of a large collection of First Nations art valued at more than $60,000 from a Gordon Head home.

The theft happened on April 2.

The collection includes several pieces by Whitehorse-based artist Calvin Morberg, as well as Inuit carvings estimated to be more than 60 years old.

Anyone with information on the thef is asked to call Saanich police at 250-472-4321.

jbell@timescolonist.com

-

Tech11 hours ago

Tech11 hours agoSave $700 Off This 4K Projector at Amazon While You Still Can – CNET

-

Investment12 hours ago

Investment12 hours agoUK Mulls New Curbs on Outbound Investment Over Security Risks – BNN Bloomberg

-

Tech10 hours ago

Tech10 hours ago'Kingdom Come: Deliverance II' Revealed In Epic New Trailer And It Looks Incredible – Forbes

-

Science12 hours ago

Science12 hours agoJeremy Hansen – The Canadian Encyclopedia

-

Sports10 hours ago

Sports10 hours agoAuston Matthews denied 70th goal as depleted Leafs lose last regular-season game – Toronto Sun

-

Business9 hours ago

BC short-term rental rules take effect May 1 – CityNews Vancouver

-

Investment9 hours ago

Investment9 hours agoBenjamin Bergen: Why would anyone invest in Canada now? – National Post

-

Art9 hours ago

Collection of First Nations art stolen from Gordon Head home – Times Colonist