Health

When every January is dry: The surprising appeal of living without alcohol – CBC.ca

It’s January, a month that many people now observe as ‘Dry January’ — a period to set aside alcohol and focus on health.

It’s not something I will be observing as a special occasion, because I don’t drink at all.

I can’t remember when I decided not to drink.

It was before I turned 19, because my celebration didn’t include the traditional first (legal) bar visit. It was before I started university, because I was able to enjoy being the only sober person at the end-of-orientation-week party, where I banked some wild stories to recount to my friends once they recovered from their hangovers.

I had had the occasional sip of alcohol as a teenager, and I thought it tasted terrible. I never enjoyed the astringent kick of wine, the malty foulness of beer.

But, honestly, who does? Alcoholic drinks taste objectively bad to most people at first. As the saying goes, you don’t drink them for the taste, and it’s likely that if alcoholic beverages were uncoupled from their euphoric effects we wouldn’t drink them at all.

When I declined a glass or bottle, I often found myself in the hot seat, being grilled on my reasons for abstaining.

The difference between me and most of my peers, I suppose, is that I wasn’t enthusiastic enough about the idea of getting buzzed to push through the nasty flavour.

My choice puzzled my friends at the time. After all, in our society we drink alcohol not only for its pleasurable effects but as a rite of passage.

Alcohol is a symbol of our transition into adulthood, and most teenagers are anxious to enjoy adult freedoms and to prove themselves worthy of adult responsibilities. We indulge in alcohol furtively when we begin to feel suffocated by the authority of our parents and guardians. We partake in alcohol openly to celebrate when our numerical age makes us legally (if not actually) independent from them.

When I declined a glass or bottle, I often found myself in the hot seat, being grilled on my reasons for abstaining. Not drinking, I’ve discovered, is one of the few purely personal choices that can make even strangers deeply uncomfortable.

It’s a singular experience to be questioned about why you don’t drink alcohol, because there are a limited number of answers people consider legitimate. An illness, a religious doctrine, a family history of alcoholism — these seem to be acceptable explanations for abstaining.

My reasons? I don’t like the taste, I’m having a good time already, I just don’t feel like it? These never seem to be good enough, so much so that I’ve sometimes fallen back on the excuse that there’s been alcoholism in my family (which is true, but not a factor) just to cut these awkward conversations short.

Why all this public concern over one aspect of my diet? I don’t like spicy food or cilantro either, but no one interrogates me about that.

Reckless libertines or hopeless degenerates?

Not drinking, on the other hand, is often taken as an affront. This is probably a legacy of the temperance movement, the organized crusade against alcohol consumption that snowballed during the 19th and early 20th centuries and eventually led to prohibition.

The temperance movement took a moral stance against alcohol and portrayed drinkers as reckless libertines or hopeless degenerates.

As a result, when you say you don’t drink, even today, the people around you begin to wonder if you’re looking down your nose at them like the temperance teetotallers of yore.

Add to that the fact that our society considers alcohol essential for relaxing, socializing, and partying, and the non-drinker becomes a very suspicious animal indeed. Is she a puritanical square, the sworn enemy of all things fun?

Each of us deserves to assess for ourselves whether drinking works for us, our bodies, and our pocketbooks.

This heap of cultural baggage makes it difficult for each of us to untangle how we really feel about alcohol from how we’re supposed to feel about it, how alcohol really affects our bodies from our expectations of how it should affect them.

I know a number of moderate drinkers who’ve recently given up alcohol after realizing they don’t actually enjoy drinking.

Alcohol is a depressant. It can lower your inhibitions and relax you, but it can also dampen your mood and make you feel gloomier than you did before. If you’re already prone to depression, drinking alcohol may not be a fantastic experience.

Others quit drinking because it’s getting in the way of their fitness goals (many alcoholic beverages are high in calories but, because they’re liquids, don’t fill you up) or because they want to save money. Newfoundlanders and Labradorians spend $1,056 per person on alcohol each year.

Each of us deserves to assess for ourselves whether drinking works for us, our bodies, and our pocketbooks. So, I propose a reality-based reset of our society’s approach to alcohol:

- Alcohol is a depressant, which can be a good thing or a bad thing depending on the circumstances and the individual drinker.

- Alcoholic drinks are not only drugs but food. You may or may not like their taste, and you may or may not want to include them as part of your diet.

- Alcohol might be a social lubricant, but you don’t need it to cut loose, act silly, and have fun. (I should know. I tend to be the friend who dances with abandon and occasionally lands on my face, despite being sober.)

Whether you’ll be enjoying the occasional drink this month or having a dry January, just remember that, if you’re of legal age, drinking is an option, not a requirement.

Read more from CBC Newfoundland and Labrador

Health

Toronto reports 2 more measles cases. Use our tool to check the spread in Canada – Toronto Star

/* OOVVUU Targeting */

const path = ‘/news/canada’;

const siteName = ‘thestar.com’;

let domain = ‘thestar.com’;

if (siteName === ‘thestar.com’)

domain = ‘thestar.com’;

else if (siteName === ‘niagarafallsreview.ca’)

domain = ‘niagara_falls_review’;

else if (siteName === ‘stcatharinesstandard.ca’)

domain = ‘st_catharines_standard’;

else if (siteName === ‘thepeterboroughexaminer.com’)

domain = ‘the_peterborough_examiner’;

else if (siteName === ‘therecord.com’)

domain = ‘the_record’;

else if (siteName === ‘thespec.com’)

domain = ‘the_spec’;

else if (siteName === ‘wellandtribune.ca’)

domain = ‘welland_tribune’;

else if (siteName === ‘bramptonguardian.com’)

domain = ‘brampton_guardian’;

else if (siteName === ‘caledonenterprise.com’)

domain = ‘caledon_enterprise’;

else if (siteName === ‘cambridgetimes.ca’)

domain = ‘cambridge_times’;

else if (siteName === ‘durhamregion.com’)

domain = ‘durham_region’;

else if (siteName === ‘guelphmercury.com’)

domain = ‘guelph_mercury’;

else if (siteName === ‘insidehalton.com’)

domain = ‘inside_halton’;

else if (siteName === ‘insideottawavalley.com’)

domain = ‘inside_ottawa_valley’;

else if (siteName === ‘mississauga.com’)

domain = ‘mississauga’;

else if (siteName === ‘muskokaregion.com’)

domain = ‘muskoka_region’;

else if (siteName === ‘newhamburgindependent.ca’)

domain = ‘new_hamburg_independent’;

else if (siteName === ‘niagarathisweek.com’)

domain = ‘niagara_this_week’;

else if (siteName === ‘northbaynipissing.com’)

domain = ‘north_bay_nipissing’;

else if (siteName === ‘northumberlandnews.com’)

domain = ‘northumberland_news’;

else if (siteName === ‘orangeville.com’)

domain = ‘orangeville’;

else if (siteName === ‘ourwindsor.ca’)

domain = ‘our_windsor’;

else if (siteName === ‘parrysound.com’)

domain = ‘parrysound’;

else if (siteName === ‘simcoe.com’)

domain = ‘simcoe’;

else if (siteName === ‘theifp.ca’)

domain = ‘the_ifp’;

else if (siteName === ‘waterloochronicle.ca’)

domain = ‘waterloo_chronicle’;

else if (siteName === ‘yorkregion.com’)

domain = ‘york_region’;

let sectionTag = ”;

try

if (domain === ‘thestar.com’ && path.indexOf(‘wires/’) = 0)

sectionTag = ‘/business’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/autos’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/autos’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/entertainment’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/entertainment’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/life’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/life’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/news’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/news’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/politics’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/politics’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/sports’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/sports’;

else if (path.indexOf(‘/opinion’) >= 0)

sectionTag = ‘/opinion’;

} catch (ex)

const descriptionUrl = ‘window.location.href’;

const vid = ‘mediainfo.reference_id’;

const cmsId = ‘2665777’;

let url = `https://pubads.g.doubleclick.net/gampad/ads?iu=/58580620/$domain/video/oovvuu$sectionTag&description_url=$descriptionUrl&vid=$vid&cmsid=$cmsId&tfcd=0&npa=0&sz=640×480&ad_rule=0&gdfp_req=1&output=vast&unviewed_position_start=1&env=vp&impl=s&correlator=`;

url = url.split(‘ ‘).join(”);

window.oovvuuReplacementAdServerURL = url;

Canada has seen a concerning rise in measles cases in the first months of 2024.

By the third week of March, the country had already recorded more than three times the number of cases as all of last year. Canada had just 12 cases of measles in 2023, up from three in 2022.

function buildUserSwitchAccountsForm()

var form = document.getElementById(‘user-local-logout-form-switch-accounts’);

if (form) return;

// build form with javascript since having a form element here breaks the payment modal.

var switchForm = document.createElement(‘form’);

switchForm.setAttribute(‘id’,’user-local-logout-form-switch-accounts’);

switchForm.setAttribute(‘method’,’post’);

switchForm.setAttribute(‘action’,’https://www.thestar.com/tncms/auth/logout/?return=https://www.thestar.com/users/login/?referer_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.thestar.com%2Fnews%2Fcanada%2Ftoronto-reports-2-more-measles-cases-use-our-tool-to-check-the-spread-in-canada%2Farticle_20aa7df4-e88f-11ee-8fad-8f8368d7ff53.html’);

switchForm.setAttribute(‘style’,’display:none;’);

var refUrl = document.createElement(‘input’); //input element, text

refUrl.setAttribute(‘type’,’hidden’);

refUrl.setAttribute(‘name’,’referer_url’);

refUrl.setAttribute(‘value’,’https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/toronto-reports-2-more-measles-cases-use-our-tool-to-check-the-spread-in-canada/article_20aa7df4-e88f-11ee-8fad-8f8368d7ff53.html’);

var submit = document.createElement(‘input’);

submit.setAttribute(‘type’,’submit’);

submit.setAttribute(‘name’,’logout’);

submit.setAttribute(‘value’,’Logout’);

switchForm.appendChild(refUrl);

switchForm.appendChild(submit);

document.getElementsByTagName(‘body’)[0].appendChild(switchForm);

function handleUserSwitchAccounts()

window.sessionStorage.removeItem(‘bd-viafoura-oidc’); // clear viafoura JWT token

// logout user before sending them to login page via return url

document.getElementById(‘user-local-logout-form-switch-accounts’).submit();

return false;

buildUserSwitchAccountsForm();

#ont-map-iframepadding:0;width:100%;border:0;overflow:hidden;

#ontario-cases-iframepadding:0;width:100%;border:0;overflow:hidden;

#province-table-iframepadding:0;width:100%;border:0;overflow:hidden;

console.log(‘=====> bRemoveLastParagraph: ‘,0);

Health

Cancer Awareness Month – Métis Nation of Alberta

Cancer Awareness Month

Posted on: Apr 18, 2024

April is Cancer Awareness Month

As we recognize Cancer Awareness Month, we stand together to raise awareness, support those affected, advocate for prevention, early detection, and continued research towards a cure. Cancer is the leading cause of death for Métis women and the second leading cause of death for Métis men. The Otipemisiwak Métis Government of the Métis Nation Within Alberta is working hard to ensure that available supports for Métis Citizens battling cancer are culturally appropriate, comprehensive, and accessible by Métis Albertans at all stages of their cancer journey.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis, whether for yourself or a loved one, can feel overwhelming, leaving you unsure of where to turn for support. In June, our government will be launching the Cancer Supports and Navigation Program which will further support Métis Albertans and their families experiencing cancer by connecting them to OMG-specific cancer resources, external resources, and providing navigation support through the health care system. This program will also include Métis-specific peer support groups for those affected by cancer.

With funding from the Canadian Partnership Against Cancer (CPAC) we have also developed the Métis Cancer Care Course to ensure that Métis Albertans have access to culturally safe and appropriate cancer services. This course is available to cancer care professionals across the country and provides an overview of who Métis people are, our culture, our approaches to health and wellbeing, our experiences with cancer care, and our cancer journey.

Together, we can make a difference in the fight against cancer and ensure equitable access to culturally safe and appropriate care for all Métis Albertans. Please click on the links below to learn more about the supports available for Métis Albertans, including our Compassionate Care: Cancer Transportation program.

I wish you all good health and happiness!

Bobbi Paul-Alook

Secretary of Health & Seniors

Health

Type 2 diabetes is not one-size-fits-all: Subtypes affect complications and treatment options – The Conversation

You may have heard of Ozempic, the “miracle drug” for weight loss, but did you know that it was actually designed as a new treatment to manage diabetes? In Canada, diabetes affects approximately 10 per cent of the general population. Of those cases, 90 per cent have Type 2 diabetes.

This metabolic disorder is characterized by persistent high blood sugar levels, which can be accompanied by secondary health challenges, including a higher risk of stroke and kidney disease.

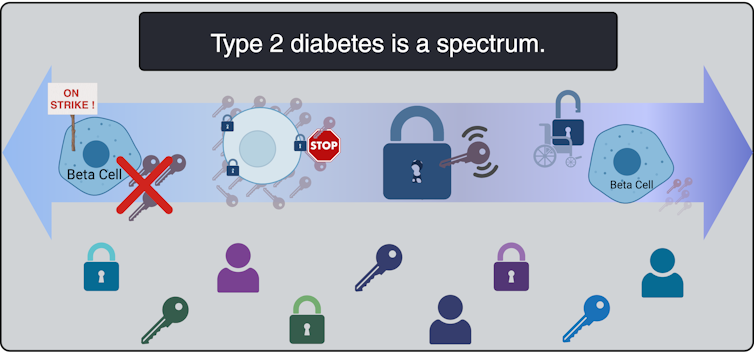

Locks and keys

In Type 2 diabetes, the body struggles to maintain blood sugar levels in an acceptable range. Every cell in the body needs sugar as an energy source, but too much sugar can be toxic to cells. This equilibrium needs to be tightly controlled and is regulated by a lock and key system.

In the body’s attempt to manage blood sugar levels and ensure that cells receive the right amount of energy, the pancreatic hormone, insulin, functions like a key. Cells cover themselves with locks that respond perfectly to insulin keys to facilitate the entry of sugar into cells.

Unfortunately, this lock and key system doesn’t always perform as expected. The body can encounter difficulties producing an adequate number of insulin keys, and/or the locks can become stubborn and unresponsive to insulin.

All forms of diabetes share the challenge of high blood sugar levels; however, diabetes is not a singular condition; it exists as a spectrum. Although diabetes is broadly categorized into two main types, Type 1 and Type 2, each presents a diversity of subtypes, especially Type 2 diabetes.

These subtypes carry their own characteristics and risks, and do not respond uniformly to the same treatments.

To better serve people living with Type 2 diabetes, and to move away from a “one size fits all” approach, it is beneficial to understand which subtype of Type 2 diabetes a person lives with. When someone needs a blood transfusion, the medical team needs to know the patient’s blood type. It should be the same for diabetes so a tailored and effective game plan can be implemented.

This article explores four unique subtypes of Type 2 diabetes, shedding light on their causes, complications and some of their specific treatment avenues.

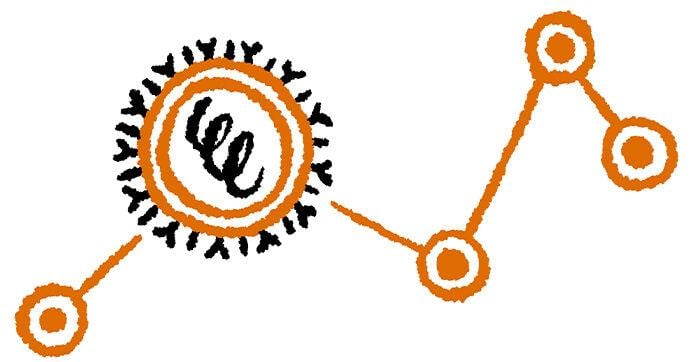

Severe insulin-deficient diabetes: We’re missing keys!

(Lili Grieco-St-Pierre, Jennifer Bruin/Created with BioRender.com)

Insulin is produced by beta cells, which are found in the pancreas. In the severe insulin-deficient diabetes (SIDD) subtype, the key factories — the beta cells — are on strike. Ultimately, there are fewer keys in the body to unlock the cells and allow entry of sugar from the blood.

SIDD primarily affects younger, leaner individuals, and unfortunately, increases the risk of eye disease and blindness, among other complications. Why the beta cells go on strike remains largely unknown, but since there is an insulin deficiency, treatment often involves insulin injections.

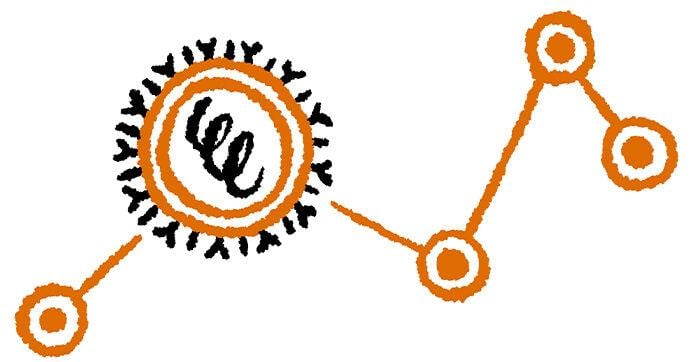

Severe insulin-resistant diabetes: But it’s always locked!

(Lili Grieco-St-Pierre, Jennifer Bruin/Created with BioRender.com)

In the severe insulin-resistant diabetes (SIRD) subtype, the locks are overstimulated and start ignoring the keys. As a result, the beta cells produce even more keys to compensate. This can be measured as high levels of insulin in the blood, also known as hyperinsulinemia.

This resistance to insulin is particularly prominent in individuals with higher body weight. Patients with SIRD have an increased risk of complications such as fatty liver disease. There are many treatment avenues for these patients but no consensus about the optimal approach; patients often require high doses of insulin.

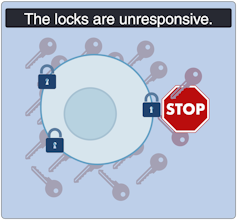

Mild obesity-related diabetes: The locks are sticky!

(Lili Grieco-St-Pierre, Jennifer Bruin/Created with BioRender.com)

Mild obesity-related (MOD) diabetes represents a nuanced aspect of Type 2 diabetes, often observed in individuals with higher body weight. Unlike more severe subtypes, MOD is characterized by a more measured response to insulin. The locks are “sticky,” so it is challenging for the key to click in place and open the lock. While MOD is connected to body weight, the comparatively less severe nature of MOD distinguishes it from other diabetes subtypes.

To minimize complications, treatment should include maintaining a healthy diet, managing body weight, and incorporating as much aerobic exercise as possible. This is where drugs like Ozempic can be prescribed to control the evolution of the disease, in part by managing body weight.

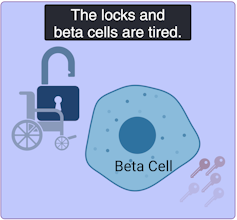

Mild age-related diabetes: I’m tired of controlling blood sugar!

(Lili Grieco-St-Pierre, Jennifer Bruin/Created with BioRender.com)

Mild age-related diabetes (MARD) happens more often in older people and typically starts later in life. With time, the key factory is not as productive, and the locks become stubborn. People with MARD find it tricky to manage their blood sugar, but it usually doesn’t lead to severe complications.

Among the different subtypes of diabetes, MARD is the most common.

Unique locks, varied keys

While efforts have been made to classify diabetes subtypes, new subtypes are still being identified, making proper clinical assessment and treatment plans challenging.

In Canada, unique cases of Type 2 diabetes were identified in Indigenous children from Northern Manitoba and Northwestern Ontario by Dr. Heather Dean and colleagues in the 1980s and 90s. Despite initial skepticism from the scientific community, which typically associated Type 2 diabetes with adults rather than children, clinical teams persisted in identifying this as a distinct subtype of Type 2 diabetes, called childhood-onset Type 2 diabetes.

Read more:

Indigenous community research partnerships can help address health inequities

Childhood-onset Type 2 diabetes is on the rise across Canada, but disproportionately affects Indigenous youth. It is undoubtedly linked to the intergenerational trauma associated with colonization in these communities. While many factors are likely involved, recent studies have discovered that exposure of a fetus to Type 2 diabetes during pregnancy increases the risk that the baby will develop diabetes later in life.

Acknowledging this distinct subtype of Type 2 diabetes in First Nations communities has led to the implementation of a community-based health action plan aimed at addressing the unique challenges faced by Indigenous Peoples. It is hoped that partnered research between communities and researchers will continue to help us understand childhood-onset Type 2 diabetes and how to effectively prevent and treat it.

A mosaic of conditions

(Lili Grieco-St-Pierre, Jennifer Bruin/Created with BioRender.com)

Type 2 diabetes is not uniform; it’s a mosaic of conditions, each with its own characteristics. Since diabetes presents so uniquely in every patient, even categorizing into subtypes does not guarantee how the disease will evolve. However, understanding these subtypes is a good starting point to help doctors create personalized plans for people living with the condition.

While Indigenous communities, lower-income households and individuals living with obesity already face a higher risk of developing Type 2 diabetes than the general population, tailored solutions may offer hope for better management. This emphasizes the urgent need for more precise assessments of diabetes subtypes to help customize therapeutic strategies and management strategies. This will improve care for all patients, including those from vulnerable and understudied populations.

-

Investment24 hours ago

Investment24 hours agoUK Mulls New Curbs on Outbound Investment Over Security Risks – BNN Bloomberg

-

Sports22 hours ago

Sports22 hours agoAuston Matthews denied 70th goal as depleted Leafs lose last regular-season game – Toronto Sun

-

Media3 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Business21 hours ago

BC short-term rental rules take effect May 1 – CityNews Vancouver

-

Media5 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Art20 hours ago

Collection of First Nations art stolen from Gordon Head home – Times Colonist

-

Investment21 hours ago

Investment21 hours agoBenjamin Bergen: Why would anyone invest in Canada now? – National Post

-

Tech23 hours ago

Tech23 hours agoSave $700 Off This 4K Projector at Amazon While You Still Can – CNET