Art

‘Without golf art, I’d be in jail’: the remarkable story of Valentino Dixon

|

|

A mere five-minute stroll from Augusta National lives a man with a more extraordinary backstory than anybody who will tee off in the upcoming Masters. Golf was largely responsible for restoring Valentino Dixon’s freedom, which in itself is poetic given his upbringing in the streets of East Side Buffalo.

“I had never set foot on a golf course before I went to prison,” Dixon explains. “I have played about 20 times now.

“Golf meant absolutely nothing to me. I grew up in a tough, inner‑city neighbourhood where it was just football and basketball. Golf was for white privileged people; at least I thought it was. It had nothing to do with a poor black kid, growing up in a drug-infested neighbourhood. I was never in a gang or anything like that but a lot of my friends got killed when I was younger.”

Dixon has rubbed shoulders with Tiger Woods and Jack Nicklaus. He has sold artwork to Michelle Obama. Yet for 27 years – he received a life sentence – Dixon was imprisoned for a shooting he was not responsible for. The delivery of justice arrived only after Dixon’s astonishing knack for reproducing golf holes on canvas received widespread publicity. He walked free in 2018, after the confession of another man – made two days after the 1991 shooting – was so belatedly accepted.

For the first seven years of his internment and despite earlier being such a promising art student Dixon did not draw a thing. His passion was refuelled by a delivery of supplies from an uncle. “He told me if I could reclaim my talent, I could reclaim my life,” says Dixon. “I started to draw again. My uncle said I may have to draw myself out of prison. That made me say to myself: ‘If I become one of the greatest artists who has ever lived, that has to get me some attention and has to get me my freedom.’ I was drawing for up to 10 hours every day for the next 20 years.

“Had I not been drawing every day, a warden would never have known me or asked me to draw the golf hole.”

The 12th at Augusta National. No ordinary golf hole. Golden Bell. “I was like: ‘Golf? I don’t know anything about golf. I’ll draw it but please, give me a break here,’” Dixon recalls. “My neighbour said I should draw more golf holes and I said: ‘Hell, no!’ He tossed some Golf Digest magazines on my bed. I started drawing courses every day and once I started I couldn’t stop.”

With this came the attention which accelerated Dixon’s bid for freedom. His voice started to be heard and the errors attached to his original trial came to light. So what was it about the appearance of golf venues that captured Dixon’s imagination from inside a cell? “Twice a year, when we were kids, our father would take us fishing. That was the only time I had real peace, those fishing trips. The golf courses reminded me of that.”

Dixon has received a medal from the Vatican. Nicklaus compared Dixon’s spirit to that of Nelson Mandela. Obama bought an item as a gift to her husband, Barack, after noting the artist’s tale on a US television show. “Everybody wants golf art,” he says. “I have some amazing art work but everyone wants golf art. I think that’s all connected to the story. Golf art got me out of prison. Without golf art, I’d still be sitting in jail right now.”

after newsletter promotion

Dixon met Woods shortly before the golfing icon won his 15th major, the Masters of 2019. “He knew my story,” says Dixon. “We chatted for five minutes. I told him he would win the Masters. He said: ‘I’ll try.’ I said: ‘No, you are going to win the Masters.’ He looked at his manager and said: ‘I like this guy.’” Woods’s victory reverberated way beyond golf.

Dixon now has a golf apparel range for sale alongside his artwork and greetings cards. He helps prisoners in their attempts to overturn injustice (“If I can get out of the situation I was in …”) and speaks in youth centres in the hope of advising teenagers to take the correct path in life. Dixon, now 53, has visited most of the iconic golf courses in the US. He was a guest, too, when the DP World Tour made a recent stop in Dubai. It seems impossible that this could ever compensate for being robbed of almost three decades of his life but Dixon is an upbeat, infectious character.

“I was never consumed by anger; that is not in my nature,” he says. “I was upset with the people who did this to me but I was around people who were angry all the time. I wasn’t like that. I could still smile, laugh, joke. I didn’t allow what was going on with me to change me. I believe in taking obstacles and using them as motivation. Where is bitterness and anger going to get me? I would only be a miserable person.”

In a month’s time the most famous names in golf will roll into Augusta in preparation for the first major of 2023. Close by will be an individual whose attitude and talent levels should draw admiring glances from those competing on golf’s hallowed turf. “I always thought outside the box as an artist,” says Dixon. “I always had big dreams for myself.” He got there in the end, following the most unimaginable of journeys.

Art

Art and Ephemera Once Owned by Pioneering Artist Mary Beth Edelson Discarded on the Street in SoHo – artnet News

This afternoon in Manhattan’s SoHo neighborhood, people walking along Mercer Street were surprised to find a trove of materials that once belonged to the late feminist artist Mary Beth Edelson, all free for the taking.

Outside of Edelson’s old studio at 110 Mercer Street, drawings, prints, and cut-out figures were sitting in cardboard boxes alongside posters from her exhibitions, monographs, and other ephemera. One box included cards that the artist’s children had given her for birthdays and mother’s days. Passersby competed with trash collectors who were loading the items into bags and throwing them into a U-Haul.

“It’s her last show,” joked her son, Nick Edelson, who had arranged for the junk guys to come and pick up what was on the street. He has been living in her former studio since the artist died in 2021 at the age of 88.

Naturally, neighbors speculated that he was clearing out his mother’s belongings in order to sell her old loft. “As you can see, we’re just clearing the basement” is all he would say.

Photo by Annie Armstrong.

Some in the crowd criticized the disposal of the material. Alessandra Pohlmann, an artist who works next door at the Judd Foundation, pulled out a drawing from the scraps that she plans to frame. “It’s deeply disrespectful,” she said. “This should not be happening.” A colleague from the foundation who was rifling through a nearby pile said, “We have to save them. If I had more space, I’d take more.”

Edelson’s estate, which is controlled by her son and represented by New York’s David Lewis Gallery, holds a significant portion of her artwork. “I’m shocked and surprised by the sudden discovery,” Lewis said over the phone. “The gallery has, of course, taken great care to preserve and champion Mary Beth’s legacy for nearly a decade now. We immediately sent a team up there to try to locate the work, but it was gone.”

Sources close to the family said that other artwork remains in storage. Museums such as the Guggenheim, Tate Modern, the Museum of Modern Art, the Brooklyn Museum, and the Whitney currently hold her work in their private collections. New York University’s Fales Library has her papers.

Edelson rose to prominence in the 1970s as one of the early voices in the feminist art movement. She is most known for her collaged works, which reimagine famed tableaux to narrate women’s history. For instance, her piece Some Living American Women Artists (1972) appropriates Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper (1494–98) to include the faces of Faith Ringgold, Agnes Martin, Yoko Ono, and Alice Neel, and others as the apostles; Georgia O’Keeffe’s face covers that of Jesus.

A lucky passerby collecting a couple of figurative cut-outs by Mary Beth Edelson. Photo by Annie Armstrong.

In all, it took about 45 minutes for the pioneering artist’s material to be removed by the trash collectors and those lucky enough to hear about what was happening.

Dealer Jordan Barse, who runs Theta Gallery, biked by and took a poster from Edelson’s 1977 show at A.I.R. gallery, “Memorials to the 9,000,000 Women Burned as Witches in the Christian Era.” Artist Keely Angel picked up handwritten notes, and said, “They smell like mouse poop. I’m glad someone got these before they did,” gesturing to the men pushing papers into trash bags.

A neighbor told one person who picked up some cut-out pieces, “Those could be worth a fortune. Don’t put it on eBay! Look into her work, and you’ll be into it.”

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

Art

Biggest Indigenous art collection – CTV News Barrie

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Biggest Indigenous art collection CTV News Barrie

Source link

Art

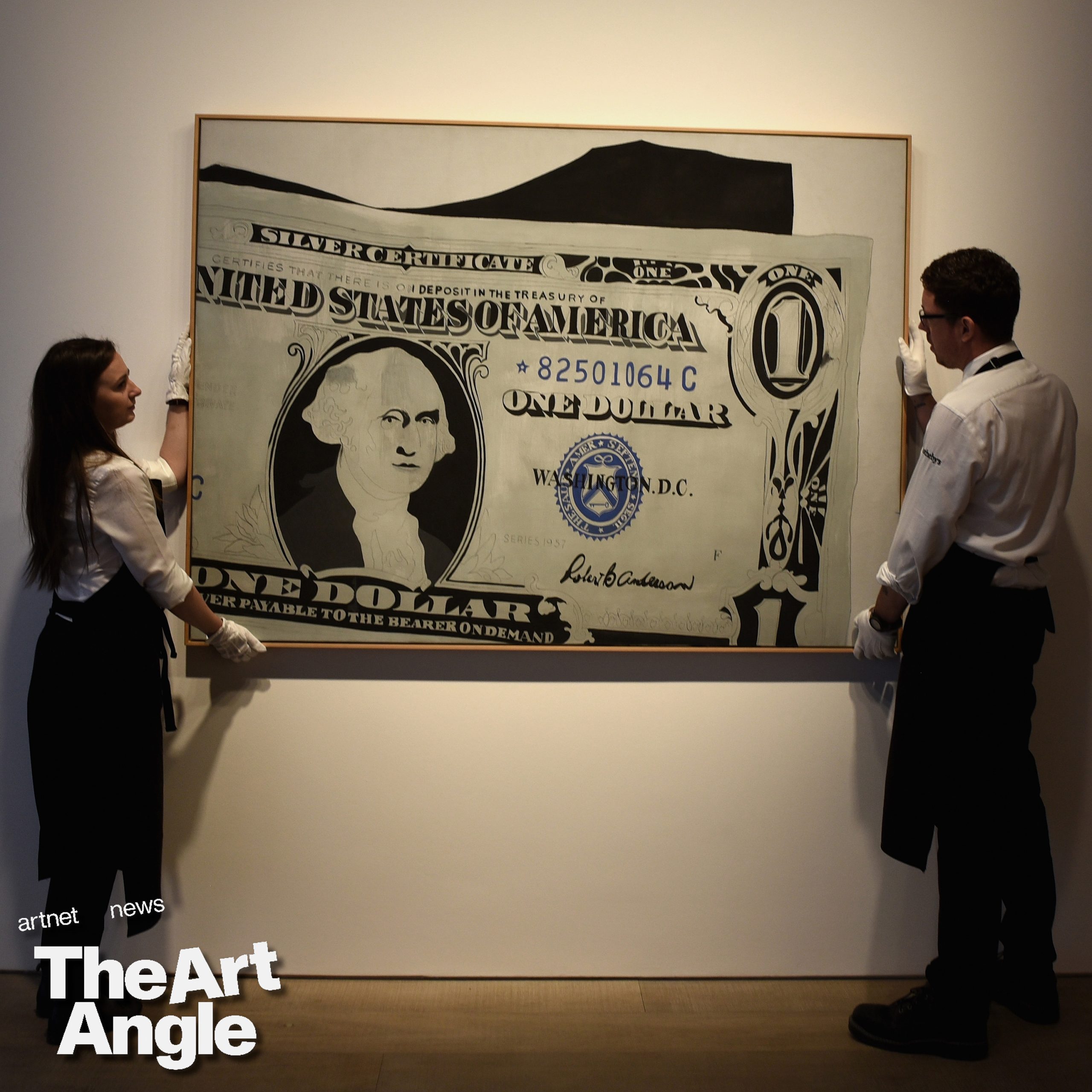

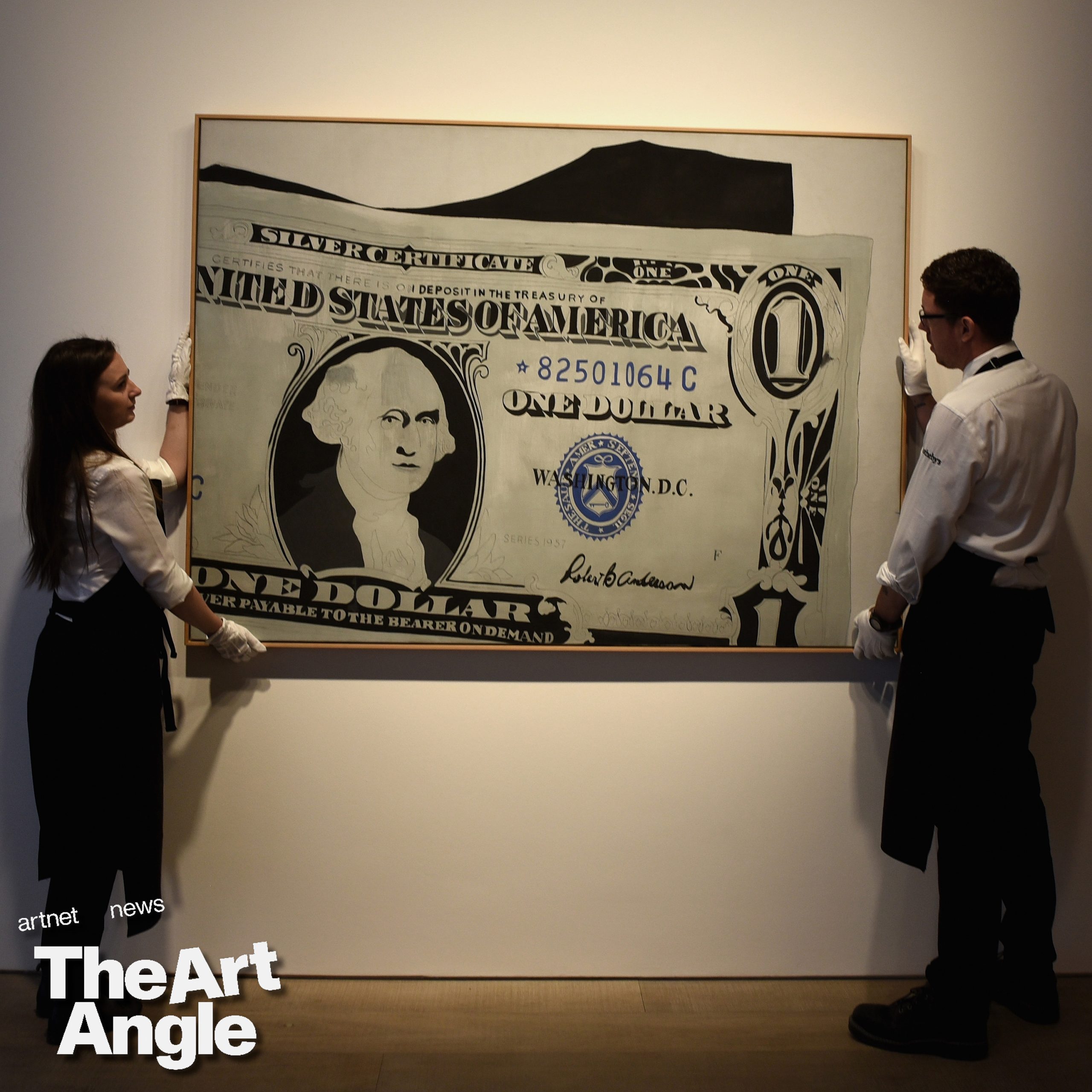

Why Are Art Resale Prices Plummeting? – artnet News

Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

The art press is filled with headlines about trophy works trading for huge sums: $195 million for an Andy Warhol, $110 million for a Jean-Michel Basquiat, $91 million for a Jeff Koons. In the popular imagination, pricy art just keeps climbing in value—up, up, and up. The truth is more complicated, as those in the industry know. Tastes change, and demand shifts. The reputations of artists rise and fall, as do their prices. Reselling art for profit is often quite difficult—it’s the exception rather than the norm. This is “the art market’s dirty secret,” Artnet senior reporter Katya Kazakina wrote last month in her weekly Art Detective column.

In her recent columns, Katya has been reporting on that very thorny topic, which has grown even thornier amid what appears to be a severe market correction. As one collector told her: “There’s a bit of a carnage in the market at the moment. Many things are not selling at all or selling for a fraction of what they used to.”

For instance, a painting by Dan Colen that was purchased fresh from a gallery a decade ago for probably around $450,000 went for only about $15,000 at auction. And Colen is not the only once-hot figure floundering. As Katya wrote: “Right now, you can often find a painting, a drawing, or a sculpture at auction for a fraction of what it would cost at a gallery. Still, art dealers keep asking—and buyers keep paying—steep prices for new works.” In the parlance of the art world, primary prices are outstripping secondary ones.

Why is this happening? And why do seemingly sophisticated collectors continue to pay immense sums for art from galleries, knowing full well that they may never recoup their investment? This week, Katya joins Artnet Pro editor Andrew Russeth on the podcast to make sense of these questions—and to cover a whole lot more.

Follow Artnet News on Facebook:

Want to stay ahead of the art world? Subscribe to our newsletter to get the breaking news, eye-opening interviews, and incisive critical takes that drive the conversation forward.

-

Media9 hours ago

DJT Stock Rises. Trump Media CEO Alleges Potential Market Manipulation. – Barron's

-

Media11 hours ago

Trump Media alerts Nasdaq to potential market manipulation from 'naked' short selling of DJT stock – CNBC

-

Investment10 hours ago

Private equity gears up for potential National Football League investments – Financial Times

-

Media24 hours ago

DJT Stock Jumps. The Truth Social Owner Is Showing Stockholders How to Block Short Sellers. – Barron's

-

Health24 hours ago

Health24 hours agoType 2 diabetes is not one-size-fits-all: Subtypes affect complications and treatment options – The Conversation

-

Business24 hours ago

Tofino, Pemberton among communities opting in to B.C.'s new short-term rental restrictions – Vancouver Sun

-

Business23 hours ago

A sunken boat dream has left a bad taste in this Tim Hortons customer's mouth – CBC.ca

-

News22 hours ago

Best in Canada: Jets Beat Canucks to Finish Season as Top Canadian Club – The Hockey News