Article content

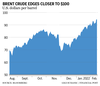

Oil’s surge toward US$100 a barrel for the first time since 2014 is threatening to deal a double-blow to the world economy by further denting growth prospects and driving up inflation.

Much of the world will take a hit as companies and consumers find bills rising and spending power squeezed by costlier food, transportation and heating

Oil’s surge toward US$100 a barrel for the first time since 2014 is threatening to deal a double-blow to the world economy by further denting growth prospects and driving up inflation.

That’s a worrying combination for the U.S. Federal Reserve and fellow central banks as they seek to contain the strongest price pressures in decades without derailing recoveries from the pandemic. Group of 20 finance chiefs meet virtually this week for the first time this year with inflation among their top concerns.

While energy exporters stand to benefit from the boom and oil’s influence on economies isn’t what it once was, much of the world will take a hit as companies and consumers find their bills rising and spending power squeezed by costlier food, transportation and heating.

According to Bloomberg Economics’ Shok model, a climb in crude to US$100 by the end of this month from around US $70 at the end of 2021 would lift inflation by about half a percentage point in the U.S. and Europe in the second half of the year.

More broadly, JPMorgan Chase & Co. warns a run-up to US$150 a barrel would almost stall the global expansion and send inflation spiralling to over 7 per cent, more than three times the rate targeted by most monetary policy makers.

“The oil shock feeds into what is now a broader inflation problem,” said long-time Fed official Peter Hooper, who’s now global head of economic research for Deutsche Bank AG. “There’s a decent chance of a significant slowing of global growth” as a result.

Hopefully this is not the straw that breaks the camel’s back

Priyanka Kishore

Oil is about 50 per cent higher than a year ago, part of a broader rally in commodity prices that’s swept up natural gas too. Among the drivers: A post-lockdown resurgence in worldwide demand, geopolitical tensions ignited by oil giant Russia and strained supply chains. Prospects for a renewed Iranian nuclear deal have at times cooled the market.

Still, the rise has been piercing. Just two years ago, oil prices plunged briefly below zero.

Fossil fuels — oil, as well as coal and natural gas — provide more than 80 per cent of the global economy’s energy. And the cost of a typical basket of them is now up more than 50 per cent from a year ago, according to Gavekal Research Ltd., a consultancy.

The energy crunch also compounds the ongoing squeeze in global supply chains, which drove up costs and delayed raw materials and finished goods.

Vivian Lau, who runs a global logistics company based in Hong Kong, said her customers are already closely watching rising fuel costs.

“The price of oil is definitely a concern,” said Lau, vice chair and group chief executive officer of Pacific Air Holdings. “The increase is happening at a time when air freight prices are already very high.”

Economists are war gaming scenarios from here.

Goldman Sachs Group Inc., which sees oil at US$100 in the third quarter, estimates a 50 per cent increase lifts headline inflation by an average of 60 basis points, with emerging economies hit most.

The International Monetary Fund recently raised its forecast for global consumer prices to an average 3.9 per cent in advanced economies this year, up from 2.3 per cent, and 5.9 per cent in emerging and developing nations.

“With inflation currently at multi-decade highs and uncertainty surrounding the inflation outlook already unprecedented, the last thing the recovering global economy needs is another leg higher in energy prices,” HSBC economists Janet Henry and James Pomeroy wrote in a Feb. 4 report. “Yet that is what it is getting.”

China, the world’s biggest oil importer and goods exporter, has so far enjoyed benign inflation. But it’s economy remains vulnerable as producers are already juggling high input costs and concerns over energy shortages.

With price pressures proving more tenacious than earlier expected, central bankers are now prioritizing inflation fighting over demand support. U.S. consumer prices surprising to a four-decade high sent shocks through the system, increasing bets the Fed will raise rates seven times this year, a faster pace than earlier expected.

Bank of England Governor Andrew Bailey this month partly justified the decision to raise U.K. interest rates by pointing to a “squeeze from energy prices.” European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde said recently that officials will “carefully examine” how energy prices will impact the economy as they signal a shift toward tightening. The Reserve Bank of India on Thursday also flagged oil prices as a risk.

To be sure, the world economy is no longer the oil guzzler it was during previous decades, especially the 1970s, and alternative energy offers some buffer. Other pandemic-era insulators include swelling household savings and higher wages amid a tight labor market.

In the U.S. the emergence of the shale oil industry means its economy is less vulnerable to fuel shocks: While consumers are paying more for gasoline, domestic producers are earning more.

Mark Zandi, chief economist for Moody’s Analytics, estimates that each US$10 per barrel increase shaves 0.1 percentage point off of economic growth the following year. That compares with a 0.3 to 0.4 point blow prior to the fracking revolution.

Other oil producers will have reason to celebrate, too.

Russia’s budget, for example, could reap more than US$65 billion in extra revenue this year, helping buffer the Kremlin against possible sanctions over Ukraine. Other emerging market producers would benefit, as would Canada and Middle Eastern economies.

But for most consumers, and central bankers, much rides on how fast and how far energy goes, particularly if economies lose momentum globally.

“A continued rapid rise can raise risks of recession-like conditions in some countries, especially if fiscal policy is also tightening notably,” said Priyanka Kishore of Oxford Economics Ltd., which estimates that every US$10 per barrel increase in oil eats around 0.2 percentage points from world growth.

“Hopefully,” she said, “this is not the straw that breaks the camel’s back.”

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

How will the U.S. election impact the Canadian economy? BNN Bloomberg

Source link

[unable to retrieve full-text content]

Trump and Musk promise economic ‘hardship’ — and voters are noticing MSNBC

Source link

OTTAWA – The Canadian economy was flat in August as high interest rates continued to weigh on consumers and businesses, while a preliminary estimate suggests it grew at an annualized rate of one per cent in the third quarter.

Statistics Canada’s gross domestic product report Thursday says growth in services-producing industries in August were offset by declines in goods-producing industries.

The manufacturing sector was the largest drag on the economy, followed by utilities, wholesale and trade and transportation and warehousing.

The report noted shutdowns at Canada’s two largest railways contributed to a decline in transportation and warehousing.

A preliminary estimate for September suggests real gross domestic product grew by 0.3 per cent.

Statistics Canada’s estimate for the third quarter is weaker than the Bank of Canada’s projection of 1.5 per cent annualized growth.

The latest economic figures suggest ongoing weakness in the Canadian economy, giving the central bank room to continue cutting interest rates.

But the size of that cut is still uncertain, with lots more data to come on inflation and the economy before the Bank of Canada’s next rate decision on Dec. 11.

“We don’t think this will ring any alarm bells for the (Bank of Canada) but it puts more emphasis on their fears around a weakening economy,” TD economist Marc Ercolao wrote.

The central bank has acknowledged repeatedly the economy is weak and that growth needs to pick back up.

Last week, the Bank of Canada delivered a half-percentage point interest rate cut in response to inflation returning to its two per cent target.

Governor Tiff Macklem wouldn’t say whether the central bank will follow up with another jumbo cut in December and instead said the central bank will take interest rate decisions one a time based on incoming economic data.

The central bank is expecting economic growth to rebound next year as rate cuts filter through the economy.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Oct. 31, 2024

The Canadian Press. All rights reserved.

Jacques Villeneuve calls thieves of late father’s bronze monument soulless idiots

B.C. port employers to launch lockout at terminals as labour disruption begins

RFK Jr. says Trump would push to remove fluoride from drinking water. ‘It’s possible,’ Trump says

Nova Scotia Liberals release four-year $2.3-billion election platform

Poilievre asks premiers to axe their sales taxes on new homes worth under $1 million

‘Canada is watching’: New northern Alberta police service trying to lead by example

Alabama Gov. Kay Ivey treated for dehydration at campaign rally

Manitoba eyes speedier approval, more Indigenous involvement in mining sector