Science

Black Hole Unmasked: Astronomers Capture First Image of Accretion Ring and Relativistic Jet

Astronomers have produced an image depicting both the accretion structure and the powerful relativistic jet of the black hole at the center of the Messier 87 galaxy. The image was generated using the Global Millimeter VLBI Array (GMVA), supplemented by the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Greenland Telescope (GLT), providing a panoramic view of the black hole and its jet at a new wavelength. The image reveals a larger, thicker ring-like structure, indicating that material falling into the black hole generates an observable emission.

Scientists used new technology to produce an unprecedented image of both the accretion process and the jet of the Messier 87 <span class=”glossaryLink” aria-describedby=”tt” data-cmtooltip=”

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”]”>black hole. Utilizing the GMVA, <span class=”glossaryLink” aria-describedby=”tt” data-cmtooltip=”

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”]”>ALMA, and GLT, they’ve observed a larger ring-like structure and a broader radiation from the inner region of the black hole, implying the existence of an outblowing wind. This breakthrough reveals previously unseen details about black holes.

An international team of scientists led by Dr. Rusen Lu from the Shanghai Astronomical Observatory (SHAO) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences has used new millimeter-wavelength observations to produce an image that shows, for the first time, both the ring-like accretion structure around a black hole, where matter falls into the black hole, and the black hole’s associated powerful relativistic jet. The source of the images was the central black hole of the prominent radio galaxy Messier 87.

The study was recently published in the journal Nature.

The image underlines for the first time the connection between the accretion flow near the central supermassive black hole and the origin of the jet. The new observations were obtained with the Global Millimeter VLBI Array (GMVA), complemented by the phased Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) and the Greenland Telescope (GLT). The addition of these two observatories has greatly enhanced the imaging capabilities of the GMVA.

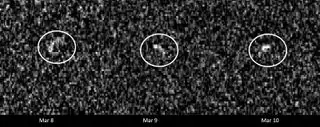

Millimeter-VLBI image of the jet and the black hole in Messier 87, obtained with the GMVA array plus ALMA and the Greenland Telescope. Credit: R.-S. Lu (SHAO), E. Ros (MPIfR), S. Dagnello (NRAO/AUI/NSF)

“Previously, we had seen both the black hole and the jet in separate images, but now we have taken a panoramic picture of the black hole together with its jet at a new wavelength,” said Dr. Lu.

The surrounding material is thought to fall into the black hole in a process known as accretion. But no one had ever imaged it directly.

According to Lu, the ring that was seen before was becoming larger and thicker at the 3.5 mm observing wavelength. “This shows that the material falling into the black hole produces additional emission that is now observed in the new image. This gives us a more complete view of the physical processes acting near the black hole,” said Lu.

The participation of ALMA and GLT in the GMVA observations and the resulting increase in resolution and sensitivity of this intercontinental network of telescopes has made it possible to image the ring-like structure in M87 for the first time at the 3.5 mm wavelength. The diameter of the ring measured by the GMVA is 64 microarcseconds, which corresponds to the size of a small (5-inch/13-cm) selfie ring light on Earth as seen by an astronaut on the Moon. This diameter is 50 percent larger than what was seen in observations by the Event Horizon Telescope at 1.3 mm, in accordance with expectations for the emission from relativistic <span class=”glossaryLink” aria-describedby=”tt” data-cmtooltip=”

” data-gt-translate-attributes=”[“attribute”:”data-cmtooltip”, “format”:”html”]”>plasma in this region.

Map of the radio telescopes used to image Messier 87 at 3.5 millimeters in the 2018 Global Millimetre VLBI Array (GMVA) campaign. Credit: Helge Rottmann, MPIfR

“With the greatly improved imaging capabilities by adding ALMA and GLT into GMVA observations, we have gained a new perspective. We do indeed see the triple-ridged jet that we knew about from earlier VLBI observations,” said Thomas Krichbaum of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy (MPIfR) in Bonn. “But now we can see how the jet emerges from the emission ring around the central supermassive black hole and we can measure the ring diameter also at another (longer) wavelength.”

The light from M87 is produced by the interplay between highly energetic electrons and magnetic fields, a phenomenon called synchrotron radiation. The new observations, at a wavelength of 3.5 mm, reveal more details about the location and energy of these electrons. They also tell us something about the nature of the black hole itself: It is not very hungry. It consumes matter at a low rate, converting only a small fraction of it into radiation.

According to Keiichi Asada from the Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics of Academia Sinica, “To understand the physical origin of the bigger and thicker ring, we had to use computer simulations to test different scenarios. As a result, we concluded that the larger extent of the ring is associated with the accretion flow.”

Kazuhiro Hada from the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan noted that the team also found something “surprising” in their data. “The radiation from the inner region close to the black hole is broader than we expected. This could mean that there is more than just gas falling in. There could also be a wind blowing out, causing turbulence and chaos around the black hole,” said Hada.

The quest to learn more about Messier 87 is not over, as further observations and a fleet of powerful telescopes continue to unlock its secrets. “Future observations at millimeter wavelengths will study the time evolution of the M87 black hole and provide a polychromatic view of the black hole with multiple color images in radio light,” said Jongho Park of the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute.

For more on this discovery:

Reference: “A ring-like accretion structure in M87 connecting its black hole and jet” by Ru-Sen Lu, Keiichi Asada, Thomas P. Krichbaum, Jongho Park, Fumie Tazaki, Hung-Yi Pu, Masanori Nakamura, Andrei Lobanov, Kazuhiro Hada, Kazunori Akiyama, Jae-Young Kim, Ivan Marti-Vidal, José L. Gómez, Tomohisa Kawashima, Feng Yuan, Eduardo Ros, Walter Alef, Silke Britzen, Michael Bremer, Avery E. Broderick, Akihiro Doi, Gabriele Giovannini, Marcello Giroletti, Paul T. P. Ho, Mareki Honma, David H. Hughes, Makoto Inoue, Wu Jiang, Motoki Kino, Shoko Koyama, Michael Lindqvist, Jun Liu, Alan P. Marscher, Satoki Matsushita, Hiroshi Nagai, Helge Rottmann, Tuomas Savolainen, Karl-Friedrich Schuster, Zhi-Qiang Shen, Pablo de Vicente, R. Craig Walker, Hai Yang, J. Anton Zensus, Juan Carlos Algaba, Alexander Allardi, Uwe Bach, Ryan Berthold, Dan Bintley, Do-Young Byun, Carolina Casadio, Shu-Hao Chang, Chih-Cheng Chang, Song-Chu Chang, Chung-Chen Chen, Ming-Tang Chen, Ryan Chilson, Tim C. Chuter, John Conway, Geoffrey B. Crew, Jessica T. Dempsey, Sven Dornbusch, Aaron Faber, Per Friberg, Javier González García, Miguel Gómez Garrido, Chih-Chiang Han, Kuo-Chang Han, Yutaka Hasegawa, Ruben Herrero-Illana, Yau-De Huang, Chih-Wei L. Huang, Violette Impellizzeri, Homin Jiang, Hao Jinchi, Taehyun Jung, Juha Kallunki, Petri Kirves, Kimihiro Kimura, Jun Yi Koay, Patrick M. Koch, Carsten Kramer, Alex Kraus, Derek Kubo, Cheng-Yu Kuo, Chao-Te Li, Lupin Chun-Che Lin, Ching-Tang Liu, Kuan-Yu Liu, Wen-Ping Lo, Li-Ming Lu, Nicholas MacDonald, Pierre Martin-Cocher, Hugo Messias, Zheng Meyer-Zhao, Anthony Minter, Dhanya G. Nair, Hiroaki Nishioka, Timothy J. Norton, George Nystrom, Hideo Ogawa, Peter Oshiro, Nimesh A. Patel, Ue-Li Pen, Yurii Pidopryhora, Nicolas Pradel, Philippe A. Raffin, Ramprasad Rao, Ignacio Ruiz, Salvador Sanchez, Paul Shaw, William Snow, T. K. Sridharan, Ranjani Srinivasan, Belén Tercero, Pablo Torne, Efthalia Traianou, Jan Wagner, Craig Walther, Ta-Shun Wei, Jun Yang and Chen-Yu Yu, 26 April 2023, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-05843-w

Science

Asteroid Apophis will visit Earth in 2029, and this European satellite will be along for the ride

The European Space Agency is fast-tracking a new mission called Ramses, which will fly to near-Earth asteroid 99942 Apophis and join the space rock in 2029 when it comes very close to our planet — closer even than the region where geosynchronous satellites sit.

Ramses is short for Rapid Apophis Mission for Space Safety and, as its name suggests, is the next phase in humanity’s efforts to learn more about near-Earth asteroids (NEOs) and how we might deflect them should one ever be discovered on a collision course with planet Earth.

In order to launch in time to rendezvous with Apophis in February 2029, scientists at the European Space Agency have been given permission to start planning Ramses even before the multinational space agency officially adopts the mission. The sanctioning and appropriation of funding for the Ramses mission will hopefully take place at ESA’s Ministerial Council meeting (involving representatives from each of ESA’s member states) in November of 2025. To arrive at Apophis in February 2029, launch would have to take place in April 2028, the agency says.

This is a big deal because large asteroids don’t come this close to Earth very often. It is thus scientifically precious that, on April 13, 2029, Apophis will pass within 19,794 miles (31,860 kilometers) of Earth. For comparison, geosynchronous orbit is 22,236 miles (35,786 km) above Earth’s surface. Such close fly-bys by asteroids hundreds of meters across (Apophis is about 1,230 feet, or 375 meters, across) only occur on average once every 5,000 to 10,000 years. Miss this one, and we’ve got a long time to wait for the next.

When Apophis was discovered in 2004, it was for a short time the most dangerous asteroid known, being classified as having the potential to impact with Earth possibly in 2029, 2036, or 2068. Should an asteroid of its size strike Earth, it could gouge out a crater several kilometers across and devastate a country with shock waves, flash heating and earth tremors. If it crashed down in the ocean, it could send a towering tsunami to devastate coastlines in multiple countries.

Over time, as our knowledge of Apophis’ orbit became more refined, however, the risk of impact greatly went down. Radar observations of the asteroid in March of 2021 reduced the uncertainty in Apophis’ orbit from hundreds of kilometers to just a few kilometers, finally removing any lingering worries about an impact — at least for the next 100 years. (Beyond 100 years, asteroid orbits can become too unpredictable to plot with any accuracy, but there’s currently no suggestion that an impact will occur after 100 years.) So, Earth is expected to be perfectly safe in 2029 when Apophis comes through. Still, scientists want to see how Apophis responds by coming so close to Earth and entering our planet’s gravitational field.

“There is still so much we have yet to learn about asteroids but, until now, we have had to travel deep into the solar system to study them and perform experiments ourselves to interact with their surface,” said Patrick Michel, who is the Director of Research at CNRS at Observatoire de la Côte d’Azur in Nice, France, in a statement. “Nature is bringing one to us and conducting the experiment itself. All we need to do is watch as Apophis is stretched and squeezed by strong tidal forces that may trigger landslides and other disturbances and reveal new material from beneath the surface.”

By arriving at Apophis before the asteroid’s close encounter with Earth, and sticking with it throughout the flyby and beyond, Ramses will be in prime position to conduct before-and-after surveys to see how Apophis reacts to Earth. By looking for disturbances Earth’s gravitational tidal forces trigger on the asteroid’s surface, Ramses will be able to learn about Apophis’ internal structure, density, porosity and composition, all of which are characteristics that we would need to first understand before considering how best to deflect a similar asteroid were one ever found to be on a collision course with our world.

Besides assisting in protecting Earth, learning about Apophis will give scientists further insights into how similar asteroids formed in the early solar system, and, in the process, how planets (including Earth) formed out of the same material.

One way we already know Earth will affect Apophis is by changing its orbit. Currently, Apophis is categorized as an Aten-type asteroid, which is what we call the class of near-Earth objects that have a shorter orbit around the sun than Earth does. Apophis currently gets as far as 0.92 astronomical units (137.6 million km, or 85.5 million miles) from the sun. However, our planet will give Apophis a gravitational nudge that will enlarge its orbit to 1.1 astronomical units (164.6 million km, or 102 million miles), such that its orbital period becomes longer than Earth’s.

It will then be classed as an Apollo-type asteroid.

Ramses won’t be alone in tracking Apophis. NASA has repurposed their OSIRIS-REx mission, which returned a sample from another near-Earth asteroid, 101955 Bennu, in 2023. However, the spacecraft, renamed OSIRIS-APEX (Apophis Explorer), won’t arrive at the asteroid until April 23, 2029, ten days after the close encounter with Earth. OSIRIS-APEX will initially perform a flyby of Apophis at a distance of about 2,500 miles (4,000 km) from the object, then return in June that year to settle into orbit around Apophis for an 18-month mission.

Related Stories:

Furthermore, the European Space Agency still plans on launching its Hera spacecraft in October 2024 to follow-up on the DART mission to the double asteroid Didymos and Dimorphos. DART impacted the latter in a test of kinetic impactor capabilities for potentially changing a hazardous asteroid’s orbit around our planet. Hera will survey the binary asteroid system and observe the crater made by DART’s sacrifice to gain a better understanding of Dimorphos’ structure and composition post-impact, so that we can place the results in context.

The more near-Earth asteroids like Dimorphos and Apophis that we study, the greater that context becomes. Perhaps, one day, the understanding that we have gained from these missions will indeed save our planet.

Science

McMaster Astronomy grad student takes a star turn in Killarney Provincial Park

Astronomy PhD candidate Veronika Dornan served as the astronomer in residence at Killarney Provincial Park. She’ll be back again in October when the nights are longer (and bug free). Dornan has delivered dozens of talks and shows at the W.J. McCallion Planetarium and in the community. (Photos by Veronika Dornan)

BY Jay Robb, Faculty of Science

July 16, 2024

Veronika Dornan followed up the April 8 total solar eclipse with another awe-inspiring celestial moment.

This time, the astronomy PhD candidate wasn’t cheering alongside thousands of people at McMaster — she was alone with a telescope in the heart of Killarney Provincial Park just before midnight.

Dornan had the park’s telescope pointed at one of the hundreds of globular star clusters that make up the Milky Way. She was seeing light from thousands of stars that had travelled more than 10,000 years to reach the Earth.

This time there was no cheering: All she could say was a quiet “wow”.

Dornan drove five hours north to spend a week at Killarney Park as the astronomer in residence. part of an outreach program run by the park in collaboration with the Allan I. Carswell Observatory at York University.

Dornan applied because the program combines her two favourite things — astronomy and the great outdoors. While she’s a lifelong camper, hiker and canoeist, it was her first trip to Killarney.

Bruce Waters, who’s taught astronomy to the public since 1981 and co-founded Stars over Killarney, warned Dornan that once she went to the park, she wouldn’t want to go anywhere else.

The park lived up to the hype. Everywhere she looked was like a painting, something “a certain Group of Seven had already thought many times over.”

She spent her days hiking the Granite Ridge, Crack and Chikanishing trails and kayaking on George Lake. At night, she went stargazing with campers — or at least tried to. The weather didn’t cooperate most evenings — instead of looking through the park’s two domed telescopes, Dornan improvised and gave talks in the amphitheatre beneath cloudy skies.

Dornan has delivered dozens of talks over the years in McMaster’s W.J. McCallion Planetarium and out in the community, but “it’s a bit more complicated when you’re talking about the stars while at the same time fighting for your life against swarms of bugs.”

When the campers called it a night and the clouds parted, Dornan spent hours observing the stars. “I seriously messed up my sleep schedule.”

She also gave astrophotography a try during her residency, capturing images of the Ring Nebula and the Great Hercules Cluster.

“People assume astronomers take their own photos. I needed quite a lot of guidance for how to take the images. It took a while to fiddle with the image properties, but I got my images.”

Dornan’s been invited back for another week-long residency in bug-free October, when longer nights offer more opportunities to explore and photograph the final frontier.

She’s aiming to defend her PhD thesis early next summer, then build a career that continues to combine research and outreach.

“Research leads to new discoveries which gives you exciting things to talk about. And if you’re not connecting with the public then what’s the point of doing research?”

Science

Where in Vancouver to see the ‘best meteor shower of the year’

Eyes to the skies, Vancouver, because between now and September 1st, stargazers can witness the ‘best meteor shower of the year’ according to NASA.

Known for its “long wakes of light and colour,” the Perseid Meteor Shower will peak on August 12th, 2024 – so consider this list a great place to start if you’re in search of a prime stargazing spots!

Grab your lawn chairs and blankets, and seek as little light pollution as possible. Here are some ideal stargazing spots to check out in and around Vancouver this summer.

Recent Posts:

This island with clear waters has one of the prettiest towns in BC

10 beautiful lake towns to visit in BC this summer

Wreck Beach

If you’re willing to brave the stairs and the regulars, it doesn’t get much better than Wreck Beach for watching the skies – for both sunsets and stargazing. The west-facing views practically eliminate immediate distractions from the city lights.

Spanish Banks Park

Spanish Banks is the perfect mixture of convenience and quality. Its location offers unobstructed views of the skies above, and it’s far enough away from downtown to mitigate some of the light pollution.

Burnaby Mountain Park

If it’s good enough for a university observatory, it’s good enough for us. Pretty much anywhere on Burnaby Mountain will offer tremendous viewpoints, but the higher you get the better (safely).

Porteau Cove

A short drive from Vancouver gets you incredible views of the Howe Sound from directly on the water. And naturally, its distance from any nearby community makes it a prime spot for stargazing.

Cypress Mountain

In addition to having one of the best viewpoints in Vancouver period, Cypress Mountain (and the road up to it) is also a great place to watch the sky. For a double-whammy, we say that you come around sunset, then hang out while the sky gets dark. Sure, it might take a few hours, but the view is worth it.

So there you have it, stargazers! Get ready to witness a dazzling show this summer.

-

Health23 hours ago

Health23 hours agoEssential Keto Cookbook Digital Plus Bonuses ($9.95) (PPU: 50232)

-

News21 hours ago

News21 hours agoJudge questions restrictions on booster payments to athletes in $2.78B NCAA settlement

-

Business11 hours ago

Business11 hours agoJapanese owner of 7-Eleven Seven & i Holdings rejects Couche-Tard takeover offer

-

Sports19 hours ago

Sports19 hours agoUS Open: Jessica Pegula beats Karolina Muchova and will face Aryna Sabalenka in the women’s final

-

Economy9 hours ago

Economy9 hours agoRecent immigrants shut out of strong wage growth as unemployment rises in Canada

-

Health20 hours ago

Health20 hours agoLP02-CB – Learn2Lick

-

Economy15 hours ago

Economy15 hours agoStatistics Canada to release August jobs report today amid labour market slowdown

-

Real eState9 hours ago

Real eState9 hours agoMontreal home sales, prices rise in August: real estate board