Article content

Endemic is a slippery term, said infectious diseases historian Esyllt Jones. It’s meant to imply that a pathogen has become stable and predictable, less whirlwind, which isn’t a great way to describe where we’re at with SARS-CoV-2.

History shows pandemic endings aren’t sudden or dramatic, but unhurried, bumpy and uneven. For some, it doesn’t end. We just stop caring. Or we care a lot less

Endemic is a slippery term, said infectious diseases historian Esyllt Jones. It’s meant to imply that a pathogen has become stable and predictable, less whirlwind, which isn’t a great way to describe where we’re at with SARS-CoV-2.

What it doesn’t necessarily mean is less virulent, or “very low” or “not a problem.” And while Spain and other countries are pivoting to the “flu-ization” of COVID, it’s not clear yet whether SARS-CoV-2 will become flu-like, because it hasn’t yet settled into a seasonal niche and has been spreading among humans for only two years, said Ross Upshur, of the University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health. The virus is still evolving, it’s not clear where it’s headed, and it likely has plenty of genetic space to explore. Omicron came out of nowhere, and though it has been linked with “milder” infections, “There is nothing in evolutionary biology that necessitates the disease becoming milder as it passes through humans,” Upshur said.

“So we need to really just keep vigilant and not just say, ‘It’s over. Yahoo.’”

The endemic narrative is more about what we desperately want, Jones and others have said — to just move on. “It’s endemic because we say it is, if you like.”

It’s endemic because we say it is, if you like

It’s time Albertans “begin to heal,” Alberta Premier Jason Kenney said this week as the province became the first in Canada to scrub its vaccine-passport scheme. Rules requiring masks in Alberta’s schools will end Monday. As of March 1, gone, too, will be the province’s work-from-home order, indoor mask mandates, capacity limits on most indoor venues and limits on social gatherings, provided hospitalizations are trending down. Saskatchewan, Quebec and Prince Edward Island are also moving to shelve restrictions keeping humans more distanced from other humans, evidence of what many are predicting — that the pandemic will have a sociological, and not biological, denouement.

Real-time pandemic dashboards tracking cases, hospitalizations and death counts have led people to believe that we can call it when the numbers click down to zero, or, in the case of the proportions vaccinated, 100, Princeton University’s David Robertson and Peter Doshi, of the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy wrote in the BMJ.

But “there is no universal definition of the epidemiological parameters of the end of a pandemic,” they said. History shows pandemic endings aren’t sudden or dramatic, but unhurried, bumpy and uneven, they wrote, “and that pandemic closure is better understood as occurring with the resumption of social life, not the achievement of specific epidemiological targets.”

“It doesn’t end. We just stop caring. Or we care a lot less,” Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health epidemiologist Jennifer Nuzzo put it more bluntly to the Washington Post. “I think for most people, it just fades into the background of our lives.”

It doesn’t end. We just stop caring. Or we care a lot less

COVID-19 certainly isn’t fading to black. There are still nearly as many people in Canada dying every day as at any point except the first wave. The single-day death toll was 165 on Jan. 31, though the number has been falling since. As the National Post’s Tom Blackwell reported this week, deaths are occurring largely among the elderly, COVID’s most vulnerable prey. And while vaccines are still holding up well against serious disease and death, Omicron has caused several times the infections as previous waves. Infection rates are still elevated, activity still widespread, Canada’s chief public health officer reported Wednesday, though seven-day average case counts are falling. Globally, the seven-day average of reported cases is 2.6 million.

Bill Hanage asks how the number of deaths in Canada has somehow become acceptable. It’s why the Harvard University epidemiologist has problems with the “new normal” and “we need to learn to live with it” narrative. What does it mean? “And who decides what that looks like?” Hanage said in an email. “At the basis of this is the notion that a certain amount of illness and death is acceptable, and that action is only merited to prevent those limits being exceeded.” As he summed it up succinctly in a tweet Wednesday, the non-scientific definition of endemic is basically “the amount of disease from which people are willing to avert their eyes.”

The technical definition implies a relatively stable rate of transmission in a defined geographic area, without huge waves ripping through the population. It exists in the population at some level, it fluctuates, but it eventually settles where it’s going to settle. But endemic doesn’t reflect severity, said Uphsur, of the U of T. “Hundreds of thousands of children die from malaria every year. That has been a stable phenomenon over time.” Tuberculosis, endemic in many places, also kills huge numbers.

“The term carries a pretty high level of subjectivity,” Jones, the University of Manitoba historian said. It also tends to be fatalistic, “and reflects to some extent what amount of death is seen as normal and acceptable, for whom. It’s contingent.”

Hanage’s worry is that that fatalism will keep us from moving quickly, if things change quickly.

Additional outbreaks are not only possible but expected

How close to endemicity might we be? “We don’t know,” he said. It depends how robust and durable the immune responses are in people who have been vaccinated or recovered from infection, or both. “Neither enter a state where they develop lifelong immunity to infection, so additional outbreaks are not only possible but expected,” Hanage said.

“Of course, if you take the non-technical meaning of ‘endemic’ as ‘something we don’t really bother about that much’ — which applies sadly to the way most people think about malaria, TB and the like because they tend to be diseases associated with poverty — that makes it a decision for humans, and the point at which humans decide they’ve got an amount of disease they can handle.”

The current thinking, said University of British Columbia evolutionary biologist Sarah Otto, is that we’ll see waves like this, like Omicron, though not as steep, and with a lower risk of hospitalization because of acquired immunity. “One thing that’s important to know, though: Those mild cases (from Omicron infections) don’t build a strong immune response. We’re seeing the best immunity in individuals who have been vaccinated, and then vaccinated with infection.”

Hanage said the sunniest scenario is that Omicron — “which don’t forget killed 15,000 Americans last week” — eases up in the next month or so, and that immunity generated by Omicron does turn out to be substantial, “such that when things pick up once more in the fall there are few severe infections.” While next winter won’t be fun for people who work in health care, neither will it be anywhere near catastrophic, Hanage said. Next-generation vaccines will hopefully offer sterilizing immunity, like measles shots, stopping all transmission and infection “and producing indirect benefits — the so-called ‘herd immunity.’”

The grimmer scenario is that a variant emerges that blends Delta’s virulence, it’s ability to cause serious sickness, with Omicron’s ability to duck some immunity acquired from vaccines and past infections. “Exhausted, we are unable to counter it with non-pharmaceutical interventions and many are sickened and die,” Hanage said. “I am not saying this is likely. I think this is unlikely. But I would not exclude it.”

Still, even in the worst case scenario Otto sees a silver lining. “We can boost quickly. We know what measures we can go back to,” like masking or reducing capacity in large indoor events in crowded spaces. “We’ve learned a lot in the hospital — which treatments work best, how to maintain oxygen levels without intubation. Even the worst-case scenario has a rosy lining in just how much we’ve learned.”

Upshur imagines SARS-CoV-2 will settle into a seasonal virus, though one “with a nasty edge to it, particularly in vulnerable populations.”

“We know this virus pops in and out of animal reservoirs,” he said. “I’m still not sold this was some kind of laboratory misadventure because we’ve seen it go into mink and zoo populations.” We need to heed the “One Health” approach that recognizes the health of humans, animals and the environment are linked, and enhance surveillance of viruses in animal populations that have the capacity to jump into humans, Upshur said. We need to shore up public health surveillance systems — more wastewater testing, more reporting and feedback from family doctors and primary care — “so that we can get an early indication that something is happening.” The more people on the planet left unvaccinated, the bigger the playground for the virus to continue to evolve variants. “We’re not safe until everyone is safe.”

If we haven’t been living with this virus for the past two years, what have we been doing?

You can’t wish away a virus by honking horns, Upshur said. And the “learn to live with it” messaging is sloppy, he said. “If we haven’t been living with this virus for the past two years, what have we been doing? What is the intended meaning of ‘living with this?’

“Let’s be clear. Let’s try to be articulate. Let’s try to be sensible about what it is we’re trying to achieve in our pandemic response.”

In some ways, we are in the endemic era, said McMaster University immunologist Dawn Bowdish. “There is no chance that COVID will ever be eliminated from the population now, it has spread everywhere, there are animal reservoirs and new babies are being born with no immunity, therefore new hosts to infect.”

In our COVID future, there will be periodic outbreaks in cancer units and hospitals and long-term care homes, Bowdish said. Loss of life in vulnerable populations. “Endemic is not a synonym for ‘easy.’”

It’s not time to ignore COVID, Otto said. But it is time to redefine what normal means for each of us. She can’t remember the last time she shook someone’s hand. She pays attention to ventilation in a room. When cases are high, she puts a new mask on when she takes the bus, careful to make sure air isn’t escaping everywhere from the sides.

“We’ve all come to just kind of learn a new normal,” she said. “And that is protecting us quite a bit, and will continue to protect us in future waves.”

National Post

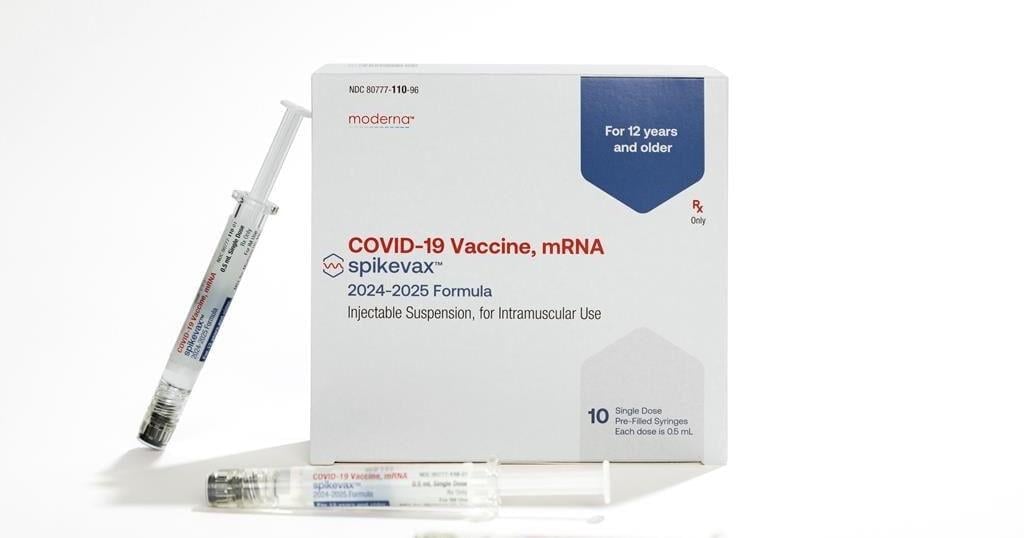

TORONTO – Health Canada has authorized Moderna’s updated COVID-19 vaccine that protects against currently circulating variants of the virus.

The mRNA vaccine, called Spikevax, has been reformulated to target the KP.2 subvariant of Omicron.

It will replace the previous version of the vaccine that was released a year ago, which targeted the XBB.1.5 subvariant of Omicron.

Health Canada recently asked provinces and territories to get rid of their older COVID-19 vaccines to ensure the most current vaccine will be used during this fall’s respiratory virus season.

Health Canada is also reviewing two other updated COVID-19 vaccines but has not yet authorized them.

They are Pfizer’s Comirnaty, which is also an mRNA vaccine, as well as Novavax’s protein-based vaccine.

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sept. 17, 2024.

Canadian Press health coverage receives support through a partnership with the Canadian Medical Association. CP is solely responsible for this content.

The Canadian Press. All rights reserved.

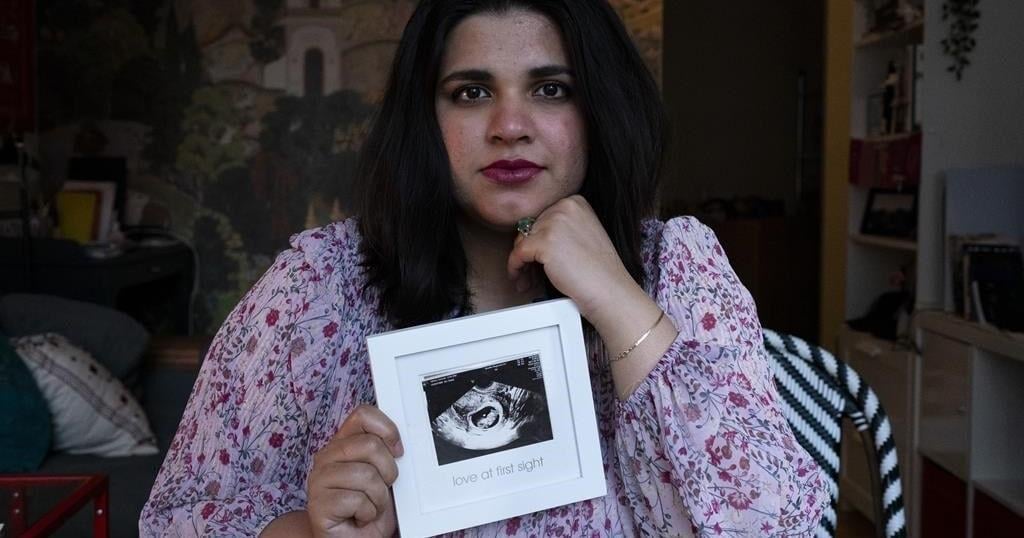

TORONTO – Sanniah Jabeen holds a sonogram of the unborn baby she lost after contracting listeria last December. Beneath, it says “love at first sight.”

Jabeen says she believes she and her baby were poisoned by a listeria outbreak linked to some plant-based milks and wants answers. An investigation continues into the recall declared July 8 of several Silk and Great Value plant-based beverages.

“I don’t even have the words. I’m still processing that,” Jabeen says of her loss. She was 18 weeks pregnant when she went into preterm labour.

The first infection linked to the recall was traced back to August 2023. One year later on Aug. 12, 2024, the Public Health Agency of Canada said three people had died and 20 were infected.

The number of cases is likely much higher, says Lawrence Goodridge, Canada Research Chair in foodborne pathogen dynamics at the University of Guelph: “For every person known, generally speaking, there’s typically 20 to 25 or maybe 30 people that are unknown.”

The case count has remained unchanged over the last month, but the Public Health Agency of Canada says it won’t declare the outbreak over until early October because of listeria’s 70-day incubation period and the reporting delays that accompany it.

Danone Canada’s head of communications said in an email Wednesday that the company is still investigating the “root cause” of the outbreak, which has been linked to a production line at a Pickering, Ont., packaging facility.

Pregnant people, adults over 60, and those with weakened immune systems are most at risk of becoming sick with severe listeriosis. If the infection spreads to an unborn baby, Health Canada says it can cause miscarriage, stillbirth, premature birth or life-threatening illness in a newborn.

The Canadian Press spoke to 10 people, from the parents of a toddler to an 89-year-old senior, who say they became sick with listeria after drinking from cartons of plant-based milk stamped with the recalled product code. Here’s a look at some of their experiences.

Sanniah Jabeen, 32, Toronto

Jabeen says she regularly drank Silk oat and almond milk in smoothies while pregnant, and began vomiting seven times a day and shivering at night in December 2023. She had “the worst headache of (her) life” when she went to the emergency room on Dec. 15.

“I just wasn’t functioning like a normal human being,” Jabeen says.

Told she was dehydrated, Jabeen was given fluids and a blood test and sent home. Four days later, she returned to hospital.

“They told me that since you’re 18 weeks, there’s nothing you can do to save your baby,” says Jabeen, who moved to Toronto from Pakistan five years ago.

Jabeen later learned she had listeriosis and an autopsy revealed her baby was infected, too.

“It broke my heart to read that report because I was just imagining my baby drinking poisoned amniotic fluid inside of me. The womb is a place where your baby is supposed to be the safest,” Jabeen said.

Jabeen’s case is likely not included in PHAC’s count. Jabeen says she was called by Health Canada and asked what dairy and fresh produce she ate – foods more commonly associated with listeria – but not asked about plant-based beverages.

She’s pregnant again, and is due in several months. At first, she was scared to eat, not knowing what caused the infection during her last pregnancy.

“Ever since I learned about the almond, oat milk situation, I’ve been feeling a bit better knowing that it wasn’t something that I did. It was something else that caused it. It wasn’t my fault,” Jabeen said.

She’s since joined a proposed class action lawsuit launched by LPC Avocates against the manufacturers and sellers of Silk and Great Value plant-based beverages. The lawsuit has not yet been certified by a judge.

Natalie Grant and her seven year-old daughter, Bowmanville, Ont.

Natalie Grant says she was in a hospital waiting room when she saw a television news report about the recall. She wondered if the dark chocolate almond milk her daughter drank daily was contaminated.

She had brought the girl to hospital because she was vomiting every half hour, constantly on the toilet with diarrhea, and had severe pain in her abdomen.

“I’m definitely thinking that this is a pretty solid chance that she’s got listeria at this point because I knew she had all the symptoms,” Grant says of seeing the news report.

Once her daughter could hold fluids, they went home and Grant cross-checked the recalled product code – 7825 – with the one on her carton. They matched.

“I called the emerg and I said I’m pretty confident she’s been exposed,” Grant said. She was told to return to the hospital if her daughter’s symptoms worsened. An hour and a half later, her fever spiked, the vomiting returned, her face flushed and her energy plummeted.

Grant says they were sent to a hospital in Ajax, Ont. and stayed two weeks while her daughter received antibiotics four times a day until she was discharged July 23.

“Knowing that my little one was just so affected and how it affected us as a family alone, there’s a bitterness left behind,” Grant said. She’s also joined the proposed class action.

Thelma Feldman, 89, Toronto

Thelma Feldman says she regularly taught yoga to friends in her condo building before getting sickened by listeria on July 2. Now, she has a walker and her body aches. She has headaches and digestive problems.

“I’m kind of depressed,” she says.

“It’s caused me a lot of physical and emotional pain.”

Much of the early days of her illness are a blur. She knows she boarded an ambulance with profuse diarrhea on July 2 and spent five days at North York General Hospital. Afterwards, she remembers Health Canada officials entering her apartment and removing Silk almond milk from her fridge, and volunteers from a community organization giving her sponge baths.

“At my age, 89, I’m not a kid anymore and healing takes longer,” Feldman says.

“I don’t even feel like being with people. I just sit at home.”

Jasmine Jiles and three-year-old Max, Kahnawake Mohawk Territory, Que.

Jasmine Jiles says her three-year-old son Max came down with flu-like symptoms and cradled his ears in what she interpreted as a sign of pain, like the one pounding in her own head, around early July.

When Jiles heard about the recall soon after, she called Danone Canada, the plant-based milk manufacturer, to find out if their Silk coconut milk was in the contaminated batch. It was, she says.

“My son is very small, he’s very young, so I asked what we do in terms of overall monitoring and she said someone from the company would get in touch within 24 to 48 hours,” Jiles says from a First Nations reserve near Montreal.

“I never got a call back. I never got an email”

At home, her son’s fever broke after three days, but gas pains stuck with him, she says. It took a couple weeks for him to get back to normal.

“In hindsight, I should have taken him (to the hospital) but we just tried to see if we could nurse him at home because wait times are pretty extreme,” Jiles says, “and I don’t have child care at the moment.”

Joseph Desmond, 50, Sydney, N.S.

Joseph Desmond says he suffered a seizure and fell off his sofa on July 9. He went to the emergency room, where they ran an electroencephalogram (EEG) test, and then returned home. Within hours, he had a second seizure and went back to hospital.

His third seizure happened the next morning while walking to the nurse’s station.

In severe cases of listeriosis, bacteria can spread to the central nervous system and cause seizures, according to Health Canada.

“The last two months have really been a nightmare,” says Desmond, who has joined the proposed lawsuit.

When he returned home from the hospital, his daughter took a carton of Silk dark chocolate almond milk out of the fridge and asked if he had heard about the recall. By that point, Desmond says he was on his second two-litre carton after finishing the first in June.

“It was pretty scary. Terrifying. I honestly thought I was going to die.”

Cheryl McCombe, 63, Haliburton, Ont.

The morning after suffering a second episode of vomiting, feverish sweats and diarrhea in the middle of the night in early July, Cheryl McCombe scrolled through the news on her phone and came across the recall.

A few years earlier, McCombe says she started drinking plant-based milks because it seemed like a healthier choice to splash in her morning coffee. On June 30, she bought two cartons of Silk cashew almond milk.

“It was on the (recall) list. I thought, ‘Oh my God, I got listeria,’” McCombe says. She called her doctor’s office and visited an urgent care clinic hoping to get tested and confirm her suspicion, but she says, “I was basically shut down at the door.”

Public Health Ontario does not recommend listeria testing for infected individuals with mild symptoms unless they are at risk of developing severe illness, such as people who are immunocompromised, elderly, pregnant or newborn.

“No wonder they couldn’t connect the dots,” she adds, referencing that it took close to a year for public health officials to find the source of the outbreak.

“I am a woman in my 60s and sometimes these signs are of, you know, when you’re vomiting and things like that, it can be a sign in women of a bigger issue,” McCombe says. She was seeking confirmation that wasn’t the case.

Disappointed, with her stomach still feeling off, she says she decided to boost her gut health with probiotics. After a couple weeks she started to feel like herself.

But since then, McCombe says, “I’m back on Kawartha Dairy cream in my coffee.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sept. 16, 2024.

Canadian Press health coverage receives support through a partnership with the Canadian Medical Association. CP is solely responsible for this content.

VANCOUVER – Mayors and other leaders from several British Columbia communities say the provincial and federal governments need to take “immediate action” to tackle mental health and public safety issues that have reached crisis levels.

Vancouver Mayor Ken Sim says it’s become “abundantly clear” that mental health and addiction issues and public safety have caused crises that are “gripping” Vancouver, and he and other politicians, First Nations leaders and law enforcement officials are pleading for federal and provincial help.

In a letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Premier David Eby, mayors say there are “three critical fronts” that require action including “mandatory care” for people with severe mental health and addiction issues.

The letter says senior governments also need to bring in “meaningful bail reform” for repeat offenders, and the federal government must improve policing at Metro Vancouver ports to stop illicit drugs from coming in and stolen vehicles from being exported.

Sim says the “current system” has failed British Columbians, and the number of people dealing with severe mental health and addiction issues due to lack of proper care has “reached a critical point.”

Vancouver Police Chief Adam Palmer says repeat violent offenders are too often released on bail due to a “revolving door of justice,” and a new approach is needed to deal with mentally ill people who “pose a serious and immediate danger to themselves and others.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Sept. 16, 2024

The Canadian Press. All rights reserved.

World Junior Girls Golf Championship coming to Toronto-area golf course

Man dead after fall from balcony as police carry out Toronto search: SIU

Politics likely pushed Air Canada toward deal with ‘unheard of’ gains for pilots

Former military leader Haydn Edmundson found not guilty of sexual assault

Canadanewsmedia news September 17, 2024: Bloc wins Montreal Liberal stronghold

Blinken is heading back to the Middle East, this time without fanfare or a visit to Israel

MK-ULTRA: Ottawa, health centre seek to dismiss Montreal brainwashing lawsuit

Donald Trump doesn’t share details about his family’s cryptocurrency venture during X launch event