Even with the walls of a volcanic crater looming behind the white-washed single-storey buildings, it would be easy to miss the sleepy town of Tao. It only takes a few moments to pass through it as you drive along the LZ-20 highway that cuts across the middle of Lanzarote, in the Canary Islands. And despite its vicinity to the Tamia volcanic crater at the heart of the island, Tao is not one of Lanzarote’s key tourist attractions.

Recently, however, the town has been receiving visitors of a very different kind – those whose interest lies not in the volcano, but in the dark grey soil that Tao is built upon. This drab, rocky material has a surprising part to play in one of this decade’s most ambitious human endeavours. It will help put humans back on the Moon.

A team of Spanish scientists have found that the basalt at a quarry near Tao bears a striking similarity to the samples of lunar regolith – the blanket of dusty and rocky debris covering the Moon’s surface – brought back to Earth by the crew of Apollo 14 in 1971. They have used it to create a sample of lunar regolith simulant that can be used to test hardware and experiments before they are sent to the Moon.

The soil sample, called LZS-1, is the latest in a list of lunar regolith simulants of varying quality that have been developed to help Nasa and other space agencies around the world prepare for missions to the Moon.

Among the first lunar simulants to be developed was Minnesota Lunar Simulant 1 (MLS-1) at the University of Minnesota in 1988 from basalt found at an abandoned quarry in Duluth, Minnesota. Researchers discovered the rocks resembled the chemical composition of soil collected from corner of the Sea of Tranquillity visited by the Apollo 11 astronauts. The dark Mare regions, or “seas”, of the Moon are composed largely of basalt rich in magnesium and iron while the lighter, highland areas are made of rocks composed mostly of calcium and aluminium.

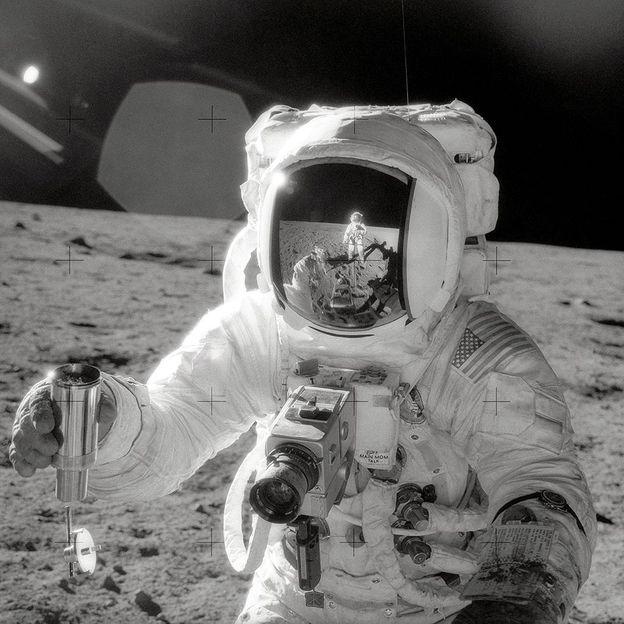

The six Apollo missions that landed on the moon between 1969 to 1972 brought back around 380kg (837lbs) of lunar soil and rocks with them to Earth. These samples were zealously protected due to their limited availability.

“It was precious and used only for important scientific research,” says John Gruener, a space scientist at the astromaterials research and exploration science division at Nasa’s Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. Yet engineers, biologists, botanists and other research teams working on projects related to the Moon need something to test their equipment and experiments on. They require substances that replicate the physical, chemical and mineral properties of the lunar regolith, not only to see how hardware such as spacecraft and spacesuits might cope with the Moon’s environment, but to test whether it might be possible to eventually grow food in the lunar soil, or use it to make building materials for constructing future lunar bases.