One stormy Monday in March, 1827, the German composer Ludwig von Beethoven passed away after a protracted illness. Bedridden since the previous Christmas, he was attacked by jaundice, his limbs and abdomen swollen, each breath a struggle.

As his associates went about the task of sorting through personal belongings, they uncovered a document Beethoven had written a quarter of a century earlier – a will beseeching his brothers make details of his condition known to the public.

Today it is no secret that one of the greatest musicians the world has ever known was functionally deaf by his mid-40s. It was a tragic irony Beethoven wished the world understood, not just from a personal perspective, but a medical one.

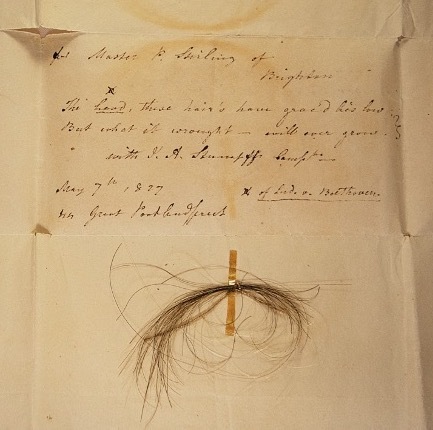

The composer would outlive his doctor by nearly two decades, yet close to two centuries after Beethoven’s death a team of researchers set out to fulfill his testament in ways he would never have dreamed possible, by genetically analyzing the DNA in authenticated samples of his hair.

“Our primary goal was to shed light on Beethoven’s health problems, which famously include progressive hearing loss, beginning in his mid- to late-20s and eventually leading to him being functionally deaf by 1818,” said biochemist Johannes Krause from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany.

The primary cause of that hearing loss has never been known, not even to his personal physician Dr Johann Adam Schmidt. What began as tinnitus in his 20s slowly gave way to a reduced tolerance for loud noise, and eventually a loss of hearing in the higher pitches, effectively ending his career as a performing artist.

For a musician, nothing could be more ironic. In a letter addressed to his brothers, Beethoven admitted he was “hopelessly afflicted”, to the point of contemplating suicide.

It wasn’t just hearing loss the composer had to deal with in his adult life. From at least the age of 22 he is said to have suffered severe abdominal pains and chronic bouts of diarrhea.

Six years before his death the first indications of liver disease appeared, an illness thought to have been, at least in part, responsible for his death at the relatively young age of 56.

In 2007 a forensic investigation into a lock of what was believed to be Beethoven’s hair suggested lead poisoning could have hastened his death, if not have been ultimately responsible for the symptoms that claimed his life.

Given the culture of drinking from lead vessels and medical treatments of the time that involved the use of lead, it’s hardly a surprising conclusion.

This latest study, published in March this year, debunks the theory, however, revealing that the hair never came from Beethoven in the first place, but rather an unknown woman.

More importantly, several locks confirmed as far more likely to be from the composer’s head demonstrate his death was probably the result of a hepatitis B infection, exacerbated by his drinking and numerous risk factors for liver disease.

As for his other conditions?

“We were unable to find a definitive cause for Beethoven’s deafness or gastrointestinal problems,” said Krause.

In some ways, we’re left with more questions on the life and death of the famous classical composer. Where did he contract hepatitis? How did a lock of woman’s hair pass as Beethoven’s own for centuries? And just what was behind his gut pains and hearing loss?

Given the team was inspired by Beethoven’s desire for the world to understand his hearing loss, it’s an unfortunate outcome. Though there was one more surprise buried among his genes.

Further investigation comparing the Y chromosome in the hair samples with those of modern relatives descending from Beethoven’s paternal line point to a mismatch. It seems there was a bit of extramarital hanky-panky happening in the generations leading up to the composer’s birth.

“This finding suggests an extrapair paternity event in his paternal line between the conception of Hendrik van Beethoven in Kampenhout, Belgium in c.1572 and the conception of Ludwig van Beethoven seven generations later in 1770, in Bonn, Germany,” said Tristan Begg, a biological anthropologist now at the University of Cambridge in the UK.

It could all be a little more than a younger Beethoven bargained for, considering the fateful request he put to paper. Never would he have dreamed of the secrets that were being preserved as his friends and associates clipped the hair from his body in the wake of that somber stormy Monday night in 1827.

This research was published in Current Biology.

An earlier version of this article was published in March 2023.